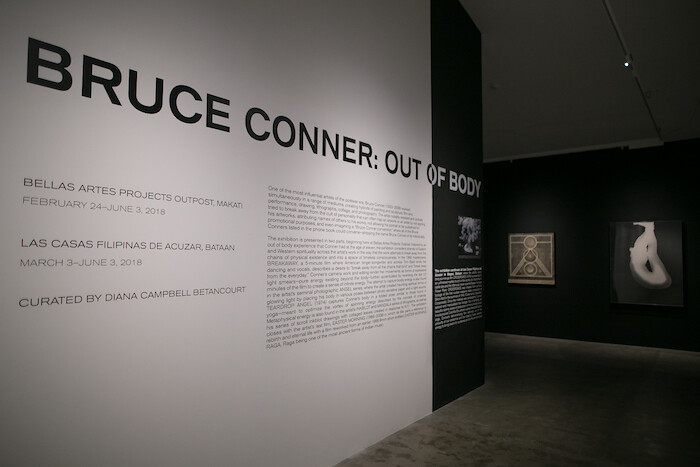

Bruce Conner’s solo exhibition, “Out of Body,” takes its title from a life-changing experience the artist had when he was eleven years old. Mesmerized by a patch of sunlight on the floor of his bedroom, he was overcome by the sensation of being “an old ancient person” within his infant body, existing “in worlds of totally different dimensions.”1 This ineffable experience was the genesis of Conner’s lifelong fascination with the mystical idea that the self and the universe were interconnected, and that the former was a microcosm of the latter. From the 1950s until his death in 2008, he worked in virtually every available medium—painting, assemblage, moving image, drawing, performance—and his polymathic approach reflected a wide-ranging interest in syncretism. He mingled spiritual beliefs in a bid to reach higher levels of consciousness, and as a way to explore countercultural alternatives to the spiritual impoverishment that he identified, and vehemently despaired of, in mainstream, consumerist American society. “Out of Body,” Conner’s first major exhibition in Southeast Asia, comprises 20 works that, by reflecting on consumerism, nuclear disasters, and spirituality, resonate with the Philippines’ past and present.

Entering the gallery, viewers first encounter the ink drawing CROSS (1963). Drawn after a sojourn in Mexico spent looking for magic mushrooms—an experience he documented in the lushly psychedelic film LOOKING FOR MUSHROOMS (1959–67/1996)—its delicate, rippling lines resemble a contour map of a landscape with a cruciform outcrop at its center. Though the drawing’s prominent central symbol is Christian, its intricate, organic design recalls nierika, the sacred geometric patterns of the Huichol people of Mexico (not to mention their peyote-fueled visions, which Conner had experienced). Blending landscapes, symbols, and vortices into hypnotic, pulsating patterns, nierika are records of hallucinatory encounters with other dimensions. The same might be said of Conner’s drawing.

Close by is “Set of Six: 601–606” (1970), a series of lithographs depicting dense, complicated patterns of circles and triangles, the result of a labor-intensive technique of building up an image out of hundreds of individual black marks. Conner conceived of these images, which resemble mandalas, the religious emblems used in meditative practice, as an externalized representation of the human psyche, an individual expression of the collective unconscious. He spent hours obsessively marking these labyrinthine forms. While their complexity invites for a meditative concentration in viewers, producing them must have constituted a form of meditation in itself, of attaining a trance-like state through repetitive actions.

The diverse theologies and philosophies that informed Conner’s work resonate with Manila’s conflicted history. For centuries, the city was under the control of local rajahs until Spain colonized it in 1571. They brought Catholic beliefs that merged with the animistic religions of the indigenous population, resulting in the folk Catholicism practiced in the Philippines today. Catholic and Chinese imagery—a common fusion found across the religious practices of Catholic Chinese Filipinos—are present in TEARDROP ANGEL (1974). In this photogram, Conner’s body is captured as a ghostly, light-filled image with a long beard and hair resembling Christ. Bent forward at the waist, his hands grip his ankles—but the image is upside-down, so that his body (as the title points out) resembles a teardrop. The spectral, monochromatic image brings to mind both the Shroud of Turin and the yin-yang symbol, while Conner’s body resembles an embryo as well as a corpse.

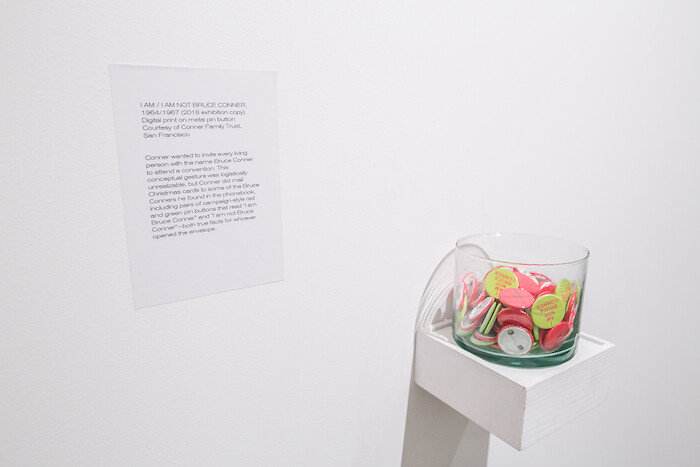

A restless iconoclast who despised the market-driven art world, in 1963, the artist conceived of a grand convention to which he would invite every living person called Bruce Conner. It never happened, but that Christmas he mailed out pairs of badges to several namesakes which read, respectively, “I AM BRUCE CONNER” and “I AM NOT BRUCE CONNER,” pink and orange replicas of which are displayed in a glass vase in the gallery (I AM / I AM NOT BRUCE CONNER, 1964–67). A year later, in 1964, Conner abandoned the macabre, found-object assemblages for which he was best known, and in 1999, after pretending to retire from art, began making work under pseudonyms. At times, his efforts at self-effacement took on a melancholic quality. His final film, EASTERN MORNING (2008), is projected in a nearby room. This mystical journey of pulsating lights and colors ends with an image of a nude female standing in a chair. She disappears from the scene, leaving an evanescent memory.

CROSSROADS (1976) is projected in a reconstructed church in Bellas Artes’ Las Casas Filipinas de Acuzar in Bataan, a Disney-esque heritage resort three hours from Manila. It is a pretty, if somewhat artificial, site for displaying art, which highlights the strong contrast between Conner’s contrarian sensibility and Manila’s proliferation of commercial galleries and shopping malls. Nevertheless, this horrifying yet beautiful film, which consists of 27 shots of the underwater nuclear bomb test at Bikini Atoll on July 25, 1946, feels apt in the broader context of twentieth-century Filipino history: the secret stockpiling of American nuclear warheads during the Cold War under Ferdinand Marcos’s regime, for example. More recently, over the Philippines and Southeast Asia more widely, North Korea’s nuclear missile tests have sent political and economic shockwaves through the archipelago. Such events affirm the universal relevance of Bruce Conner’s prophetic work.

Rudolf Frieling and Gary Garrels (eds.), Bruce Conner: It’s All True (San Francisco: University of California Press, 2016), 333.