Fitting its island context, the 2019 Lofoten International Art Festival (LIAF) takes the intertidal zone as its inspiration, though, for the life of me, I had no idea what the intertidal zone was. After a quick dive into oceanographic terms, I learned that it is the area of land that meets the sea, and is either flooded or left open to the air, depending on the tide. Although the exhibition’s curators, Neal Cahoon, Torill Østby Haaland, Hilde Methi, and Karolin Tampere, present various works that take this phenomenon quite literally, they have also put together a festival that chooses to wade into spaces of translation and transitions between that which was and that which may come next.

Take, for example, artist Signe Lidén’s invigorating installation, The Tidal Sense (2019). Comprised of a 28-by-6-meter hemp canopy, the work is hung as a taut awning across one of the floors of the Lofotposten Building, a former newspaper complex that is one of the four exhibition spaces of this iteration of the biennial. Mapping the span of an intertidal zone in the nearby village of Ramberg, the work was first stretched across the shoreline so as to create a kind of sounding board in which the crash of surf and the roar of the wind were picked up by this membrane and recorded through the use of various microphones. Transposed into the exhibition, the canvas is made into a kind of ad hoc speaker through the use of transducers, only that in order to hear these subtle recordings, audience members have to stand directly under its sail and physically place their heads on it. Advancing a narrative on the role that sound bears in establishing a sense of place, Lidén also presented a small display in which a podcast interweaves a set of reflective monologues to an unheard interviewer on tides and waterways with local school children, a neurologist, a biologist, and an indigenous studies professor and author. Of particular note, Grace Dillon, the indigenous studies scholar, treats listeners to a lexicon of indigenous words, which not only introduce concepts of time, place, and togetherness, but in effect conjure entire worldviews alternative to traditional western modes of existence.

An interest in storytelling and its ability to entertain, educate, and preserve heritage runs through many of the works on view. In Wind Theater (2018–19), artist collective Futurefarmers present a suite of works on the local community of Digermulen on Hinnøya, which—unlike most of the other islands in the Lofoten archipelago—was historically denied an access road that would connect it with the rest of the region by various governmental planning agencies. This lack of development economically strangled the settlement so the town’s women decided to build their own infrastructure. Lacking sufficient resources, these women, who call themselves the Dynamite Girls, engaged in a series of media stunts, such as inviting politicians to successive ribbon-cutting ceremonies for a road they didn’t fund. As their resistance grew, the story became a national cause célèbre. In addition to documentary videos about life in Digermulen, Futurefarmers placed a small portable radio in their installation to rebroadcast a taped national public radio program in which the Dynamite Girls held an open telephone line to a blasting site so that the country could collectively listen to their achievements—the event was phoned in because the station, NRK, didn’t send a correspondent. As you may imagine, this isn’t the best way to broadcast such a thing, and the explosion was not picked by the phone’s receiver. Instead of letting the opportunity go to waste, the Dynamites quickly slammed the doors of nearby cars as a proxy. The exhibition’s opening found many Norwegians huddling round the portable radio, and in so doing, reenacted the ambience and hope of the original live broadcast from 1993.

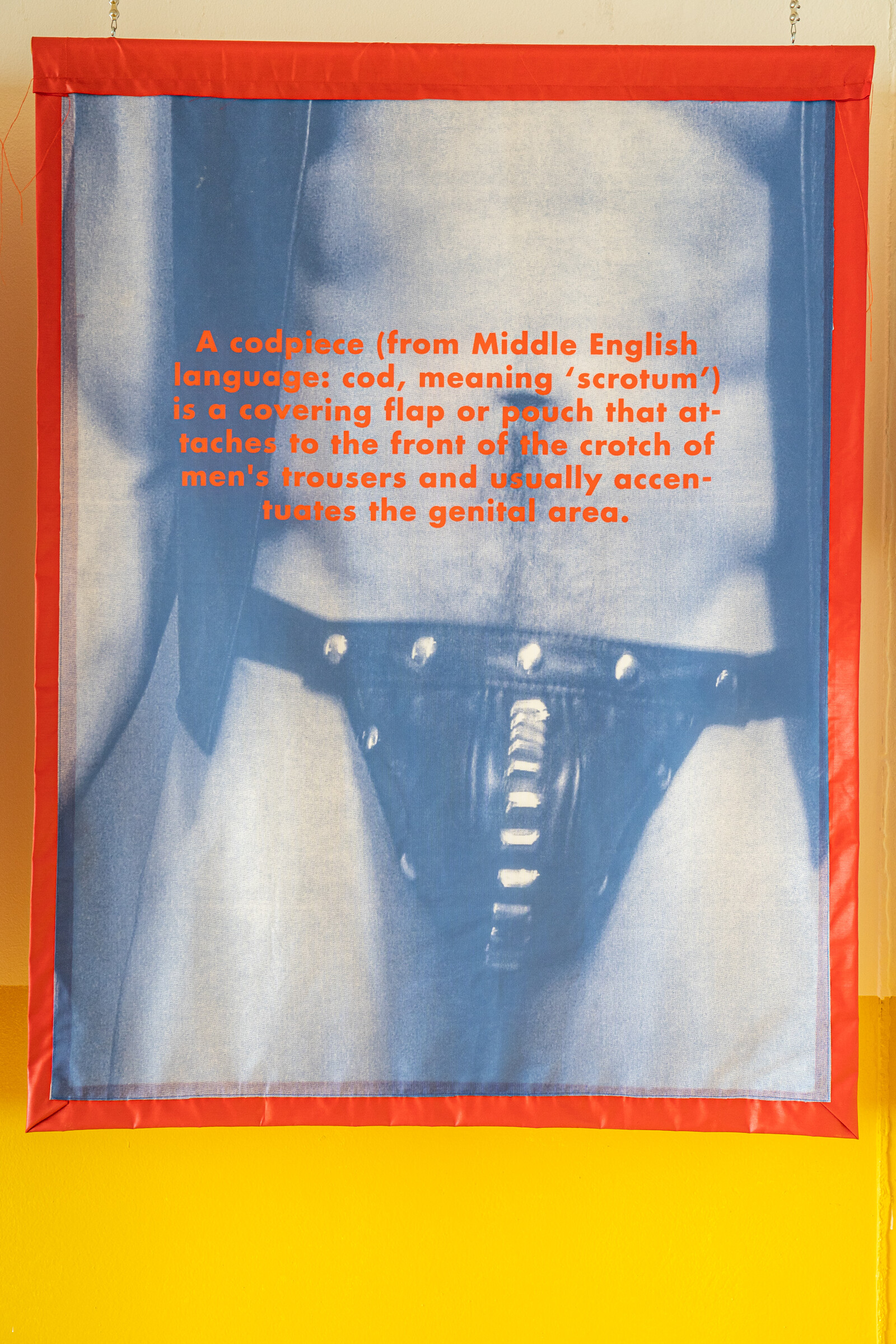

Just who gets to be the storyteller is of course an exercise in power. In order to decenter heteronormative authorship and its related characterizations, Jackie Karuti’s Black Birds (2017) reimagines an East African fairy tale through an oneiric shadow theater–like film made by moving objects on an overhead projector so as to depict the loss of innocence of a group of girls who undergo a heroine’s journey through a fantastical sea voyage. Likewise, João Pedro Vale and Nuno Alexandre Ferreira hosted a sort of parody cooking show entitled The Semiotics of Cod (2019) in which the artists mused on the mythology of bacalao, a kind of salted cod that paradoxically became the Portuguese national dish even though the species cannot be found near Portugal. This performance, which culminated in the artists serving bites of bacalao to visitors, queered their country’s history of maritime-based colonialism through their own histories of cruising as well as the shared etymological relation between the name of the fish, and codpieces, the kind of flap attached to the crotch of men’s trousers in Renaissance dress.

Esoteric, rather than erotic, ecstasy was evoked by Damla Kilickiran, who displayed a set of 78 seductive color drawings, each featuring abstract diagrams of tessellated platonic solids developed through her daily séance practice. Joining these, Kilickiran bathed a darkened hall of the Lofotposten Building with Psykografier (2018), four psychedelic screensaver–like animations culled from the “collective conscious” of cyberspace and projected onto the crumbling walls of the former newspaper office. While they could be read as a cypher for the internet’s disruption of news media, their ethereal forms, when considered against the building’s fate of being adapted into luxury pieds-à-terre after the exhibition, alluded to the haunting transformation of the islands’ culture into a self-exoticizing destination made to perform for the boatloads of tourists rushing into the port of Svolvaer via the Norwegian cruise industry.

Possibly as a form of opposition to the hospitality industry, LIAF appears to wallow in how art and authentic human attachments promote a greater feeling of belonging and responsibility; to this end, many of the artists developed their work by taking up long residencies in Lofoten. Whether these sentiments can surf the wave of a changing ecology or not, the opening characteristically found a courageous Digermulen resident fighting the good fight as he ran for political office on the platform of blocking a proposed new hotel tower drastically taller than Svolvaer’s currently tallest building, also a hotel.

.jpg,1600)