The number of Tel Avivan galleries mounting consecutive group shows is a symptom of the Israeli art market’s gloomy state. While you might assume that Dvir’s latest group exhibition—its second in a row—is another driven by commercial imperatives, it does draw concrete formal and contextual ties between works by major artists including Lawrence Weiner, Miroslaw Balka, Douglas Gordon, Shilpa Gupta, and Jonathan Monk.

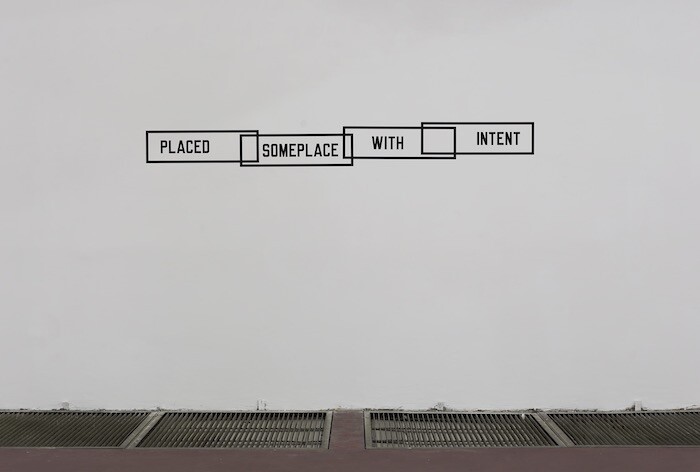

Weiner’s Placed Someplace with Intent (2014), which gives the show its title, seems the most fitting of several text-based works in the show. The sentence might humorously describe Mircea Cantor’s sculpture Supposing I could hear that sound. Now (2015), a huge concrete coulisse adorned with thick concrete ropes, resting on two readymade shofars (ancient Jewish horns). The shofars peek out like two feet of a crushed, helpless creature. Cantor’s at times austere, at times whimsical use of readymades is also present in two works by Barak Ravitz, a promising young Israeli artist. In one, a black rubber cast of a raven is laying on the floor as if dead, its head resting on a black cotton thread ball that runs through its body (Knitter, 2016). It lies next to Cantor’s photograph Hiatus (2008), depicting a strange geometric wooden sculpture carved into a tree trunk in a Transylvanian forest. Together, these works form a mysterious, uncanny world of archetypes and religious symbols.

Some of Balka’s works, presented on a single wall, address Jewish trauma more concretely. The text piece Four Something (2012) follows Weiner’s graphic use of words, but uses very specific ones: a short dialogue taken from Claude Lanzmann’s documentary film Shoah (1985). Martha Michelson, the wife of a Nazi schoolteacher in Chelmno, is asked if she knows how many Jews were killed there: “Four something… Yes, I knew it had a four in it.” Numerical memory appears again in 13 cm AF (2015), a tall rectangle of gray cardboard striped by a single, darker horizontal band measuring 13 cm in width. This strip marks how much Anne Frank grew during two years hiding from the Nazis, and is made with myrrh, a natural oil used in the ancient Jewish Temple. It echoes the marking made by Frank’s parents on the wall of their house, but is hung so that the 13 cm marking her growth in captivity are placed slightly above the top of an adult’s head. The piece suggests the impossibility of any purely quantitative representation of the Holocaust (which is exactly what Lanzmann masterfully confronted in his Shoah). Balka provides two intelligent attempts to deal with the delicate subject of collective trauma, but their presentation next to a series of framed, sooty photographs that were burnt in the artist’s 1993 studio fire situates this wall in the realm of hackneyed Holocaust representations.

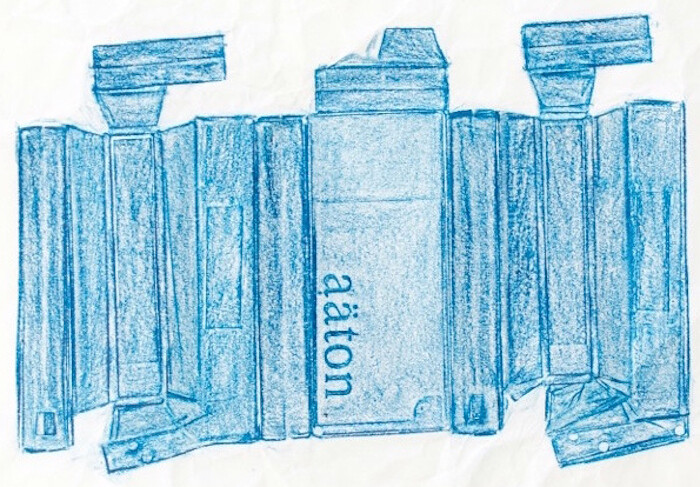

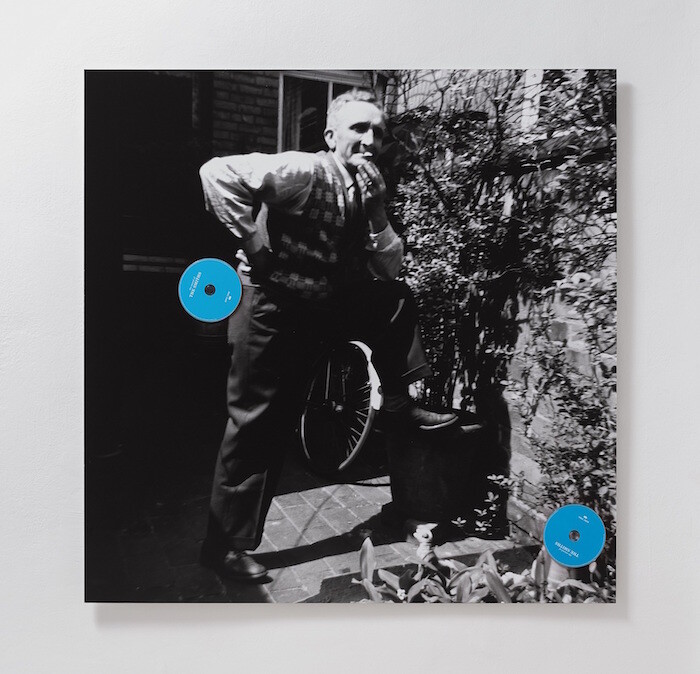

Jennifer Bornstein also attempts to capture that which is missing. In a series of works on paper—including Digital Wristwatch, Five Hiking Socks, and Aaton Battery (all 2016)—she copied her father’s belongings by imprinting the objects with blue encaustic wax on Japanese Kozo paper, in a child-like rubbing technique used here to produce almost forensic evidence of the father’s existence. The absent image is at the heart, too, of Eli Petel’s sensitive eight-part work of monochromatic paper cutouts resembling the continents (Passport, 2016). The eighth image outlines not a continent, but the artist’s kneeling body as seen from behind. This thoughtfully ties together notions of representation and identity, punning on the passepartout. Other works hint at the current crisis of nomadism: in Gupta’s series of small black-and-white photographs, a white cloud of smoke is seen in various interiors (“Untitled,” 2016). The various images anthropomorphize the illusive substance as it seems to travel between empty locations. Hung low from the ceiling so that it nearly brushes the floor, Balka’s 180 x 180 x 53/domestic shelter (2015) is a triangular roof covered with orientalist rugs. The roof over your head becomes the ground under your feet, until both lose their function.

When Weiner’s work Placed Someplace with Intent was first presented in Madrid, at Parra & Romero gallery, he invited four artists (Ibon Aranberri, David Lamelas, Antoni Muntadas, and Isidoro Valcárcel Medina) to translate the sentence to into their native languages—respectively Basque, Spanish, Catalonian, and Galician—thus injecting the words with lingual-territorial meanings. Presented here in a very different context, the phrase frames the exhibition as a careful placement of works, their intents dependent on their viewing conditions. While the individual works hold high artistic value, their accumulation over the gallery’s three floors seems intended ultimately to point towards its own house style—post-minimal, post-conceptual, monochromatic, reserved, and bittersweet.