En route to Helsinki this February, as the plane dropped through patchy cloud on its descent to the Finnish capital, I peered through the window at the country’s south coast. Instead of a clean line demarcating land from sea, there was a fragmentary confusion of dark islands set amid wastes of ice. From the elevated vantage of the plane, the arrangement of earth and water, snow and stone formed a dazzling pattern of light and dark, making it hard to tell where Finland ended and the Baltic Sea began. Here was a place where boundaries, if not exactly meaningless, were complex and hard to map. For the next three days, walking the snow-laden streets to the national museums, commercial galleries, and artist-run spaces of the city, the ongoing negotiation of borders—geographical, political, and cultural—emerged as a pertinent theme.

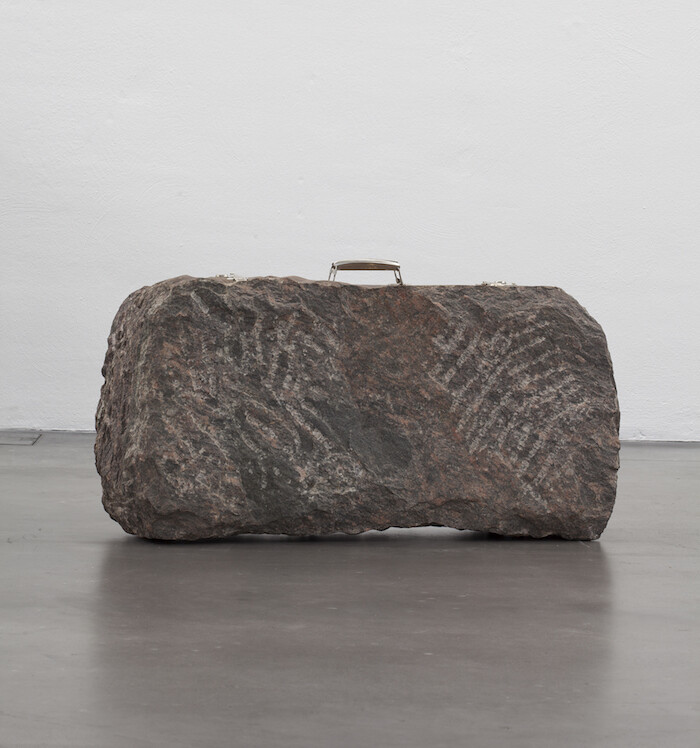

At Kiasma, the recently renovated airy museum in central Helsinki, the group exhibition “There and Back Again” presented contemporary art from the Baltic region. As the title of the show made explicit, Baltic art and identity were here understood through the lens of transport, of departure and return, implying that travel between nations was a defining feature of the region. Being in-between, in transit, on the move were motifs in the show. From a boat constructed from empty beer cans by Estonian artist Karel Koplimets (Case No. 13. Waiting for the Ship of Empties, 2017) to Lithuanian artist Gediminas Urbonas’s suitcase carved from stone (Matkalaukku [Suitcase], 1988) and a rudimentary airplane folded from rust-brown sheets of used tin roofing (Nousu (Lentokone) [Uprising (The Aircraft)], 2015) by Estonian artist Flo Kasearu, there was a shared sense of artists attempting to offer concrete metaphors for unstable identities. To move between cultures and nations, these works suggest, involves acts of transformation. Luggage becomes deadweight, rooting you to the spot, while a sheltering roof becomes a symbol of flight.

“There and Back Again” evidences an artistic community that communicates across seas and geopolitical divisions. It was therefore ironic that the prevailing mood was of loneliness, particularly apparent in the video works. Finnish artist Artor Jesus Inkerö’s video of a young, stereotypically macho man killing time in the luxurious non-space of a Helsinki hotel (Bubble, 2017) chimed with the desolate mood of Latvian artist Katrina Neiburga’s three-channel video installation depicting the interiors of bathrooms, bedrooms, and cars (Solitude, 2005). In Dancing Home (1995), Jaan Toomik filmed himself on the empty rear deck of a ferry between the island of Hiiumaa and mainland Estonia, dancing alone to the rhythmical chug of its engine, as the ocean fell away behind him. Watching the video, I was struck by its similarity to Gillian Wearing’s Dancing in Peckham (1994), in which the artist dances alone in a shopping center, questioning the role of inhibition and choreography in urban space. Toomik’s shimmying solo act, by contrast, illustrates how travel unavoidably involves a dislocation from home, both liberating (he’s dancing) and alienating (he’s dancing on his own).

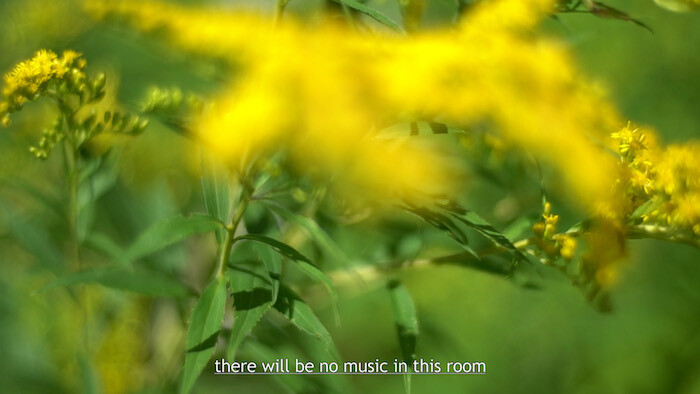

In today’s fragmentary political climate, however, artists who grapple most directly with identity politics are likely to be found more widely than the Baltics. On the first floor of Kiasma, Korakrit Arunanondchai’s solo exhibition explored cultural hybridity, with a focus on the artist’s family history and his relationship to his hometown of Bangkok. In the main space, the installation With History in a Room Filled With People With Funny Names 4 (2017) featured a tortured, twisted garden assembled from dirt, sea shells, straggly metal poles and wires, and blown-glass containers lit from within and glowing like coals. It was a frenzied, painful-seeming installation, a science-fictional terrain livid with volcanic colors and abrasive textures. Next door, the video Painting With History in a Room Filled With People With Funny Names 3 (2015) transposed the frenetic, mash-up strategy into moving images. Here, Arunanondchai spliced glossy music-video footage—in which the artist appears as his denim-clad alter ego The Denim Painter, rapping about Bangkok to a skittering trap-music backbeat—with drone footage of rural Thailand, documentation of a performance by the genderfluid artist Boychild, and found footage of religious ceremonies and wildlife. The overall effect was mesmerizing.

Later that afternoon, while trudging through a snow-covered park toward Helsinki’s commercial gallery district, a few statements from Arunanondchai’s video resonated in my head: “the world is a porous membrane,” “there is no such thing as purity.” The lines were odes to infection and contamination, offering a progressive celebration of messiness and multiplicity. It was with a contrasting sense of trepidation that I approached Galleria Sinne for “Inna di Video Light,” a solo show by Internet_Dollz, a collaborative project by Anna Rokka and Rut Karin Zettergren. At a dinner on the previous night, I had asked a young artist for tips about which exhibitions were good and worth visiting. After a thoughtful pause, she said, “Well, sometimes it’s useful to see the bad shows too.” Her point, reasonably enough, was that the most controversial shows are also the most talked about, and therefore reveal, through the ripple of vexation they cause, something about a city’s artistic community.

It wasn’t hard to see why “Inna di Video Light” was being talked about. Projected on screens around the space, the floor of which was littered with discarded, dimly glimmering DVDs, was a multi-channel video. Framed as a kind of gonzo ethnographic study, the video featured the white female artists, dressed in white, visiting dancehalls in Jamaica in order to offer an outsider’s perspective on daggering and “video lights” (the name for the professional filmmakers who document dancehall events using cameras and high-powered flashlights). Offering their own infinitely more problematic version of a video light, the work’s white subjects danced with and roamed amid the crowd, offering smirking, knowing glances to the camera, as though to express through gaze alone the bizarreness and exoticism of the black milieu of which she was so blatantly not a part. Tone-deaf in concept and execution, “Inna di Video Light” was a flagrantly insensitive show. Provocation was almost certainly the aim—but provocation at what cost? While Arunanondchai and several artists in “There and Back Again” offered illuminating reflections on displaced identities in politically uncertain times, here was a crass example of how outmoded stereotypes can at times prove dismayingly attractive to artists.

As we left the space, a friend joked that Internet_Dollz appeared to have had as much respect for Caribbean culture as they had for the DVDs we were invited to step on as we walked around the space. Unsure if the Dollz were guilty of appropriation, degradation, or both, I was however certain that there are better—as in less bullishly self-centered—approaches to engaging with cultural otherness through art. And so it was with a sense of relief that we arrived at SIC, an artist-run space that occupies a large, chilly floor of an old industrial building on the southwest edge of the harbor. Dafna Maimon’s solo show “Family Business” (all works 2018) offered a significantly more accomplished and stimulating take on the cross-cultural theme, drawing on the artist’s own history to reflect on shifting attitudes to immigration.

The main room of the space was a reconstruction of Finland’s first kebab and falafel stand, opened in 1985 by the artist’s Israeli father in the Forum shopping center in central Helsinki. In Maimon’s version, the parasol-covered tables were dotted with oversized fabric lettuce leaves, pita breads sprouting Barbie doll legs, slogans suspended from the ceiling (“Life’s short, Kebab’s big”), and other cartoonish touches, which lent the space the feel of a playground. During a performance on the show’s opening night, Maimon had offered food in exchange for spoken words. A comically irrational price list informed me that one falafel ball cost 15 words, two cost 59, seven cost 39, and so on: “WE GIVE AND TAKE MOUTH TO MOUTH!” I read beneath the prices, not quite sure what to make of this madcap, utopian food court. In the absence of performers, the installation felt a little centerless, like a stage set waiting to be activated. Still, this was a playful reflection on how personal and national memory interconnect across generations and geographies—from father to daughter, from Israel to Finland, from the Mediterranean to the Baltic.