“Songs for Sabotage,” the fourth New Museum Triennial, is suavely branded as a survey of 26 subversive practices from around the world. The curators, Gary Carrion-Murayari and Alex Gartenfeld, frame the exhibition with an astute awareness of the challenges it faces as an institution that would seem to reify the repressive ideologies it purports to dismantle. In his catalog text, Gartenfeld—who might be considered the most precocious institutional mind of the generation still younger than Jesus, and thus keenly attuned to the trappings of dwelling on age—addresses the wise move to excise the word “generational” from the show’s identity (though it remains a round-up of artists under 35), writing, as a kind of disclaimer: “Previously described as a ‘generational’ survey, the Triennial implicitly and explicitly weds the notion of youth to international movements in order to link artistic potential (both criticality and marketability) to demographics.”

Further, he parses how the Triennial is positioned in such a way that makes it an increasingly impossible curatorial undertaking: “The implicit task of the Triennial is to contrast the spirit of internationalism—solidarity, diversity, autonomy—with the deleterious, dominating processes of globalization, and to observe and propose points of connection that might be liberatory, rather than merely advancing the agenda of neoliberalism by introducing young international practitioners to the market.”

But at its core the New Museum Triennial is a cotillion introducing young international practitioners to the market. And the curators’ understanding of a systemic problem like this doesn’t diminish it. The exhibition is geographically diverse, and most of the artists work with galleries outside of what is typically considered the power structure (if they work with galleries at all). But accumulating them here isn’t a non-commercial gesture; on the contrary, it’s a 2wider casting of the net. There won’t be a feeding frenzy on all the artists in the show, but it’s really not about the artists, anyway. The most conspicuous effect of introducing them to the market via the museum is the institution’s own accrual of various capital—intellectual, geopolitical, and, with regard to claiming names untouched by rival fundraisers, territorial. The fastidiously heterogeneous selection of artists constitutes a risk-adverse portfolio that secures growth for a museum whose projection of its identity, in an especially crowded local context, has been remarkably ambitious.

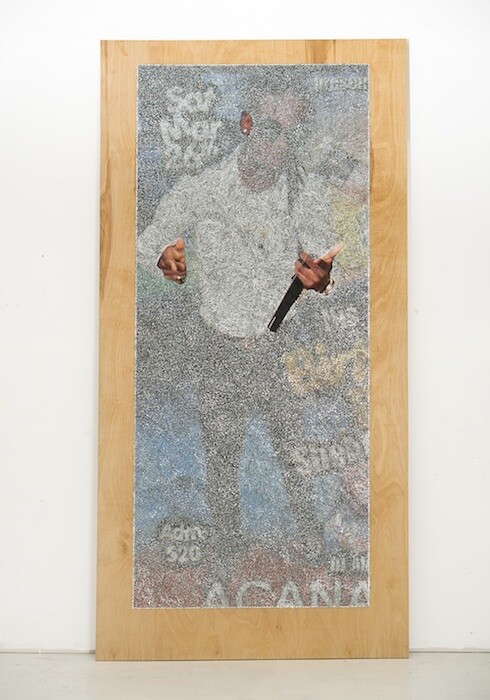

The fourth floor is spare and striking, anchored by two of the exhibition’s most memorable pieces: Diamond Stingily’s ominous, oneiric swing set E.L.G. (2018), and Manolis D. Lemos’s droning loop of an anarchic choreography called dusk and dawn look just the same (riot tourism) (2017). A brick balances atop Stingily’s ten-foot-tall piece, perfectly and precariously, adding an air of danger to the sparse, Goberesque form whose other main features are an overly long ladder stretching skyward and a long chain weighted with something that looks like a piece of plumbing equipment. The ruddy block stands out from the otherwise silver structure and imbues the entire room with a sense of gravity of doomed potential. There’s an airiness and a weightiness to the mise-en-scène: the almost fractal undulations of staples coating Wilmer Wilson IV’s occluded figures appropriated from street advertisements; Tiril Hasselknippe’s welded steel parts hanging from the ceiling like disembodied dinosaur pieces; and, as a non-metallic counterpoint, Gresham Tapiwa Nyaude’s motley canvases skewering Zimbabwe’s sociopolitical anguishes, the largest of which, The New Zimbabwe (2018), is emblazoned with Shona words that translate to “wealth takes turns.”

There is a refined tension held in this room between the elegance of the installed works and the promise of revolt contained in their encoded messages. The sonic glue is the mystical yawning of Lemos’s degraded, saturated video pushing down a commercial thoroughfare leading to Athens’s Omonia Square. It follows a mass of some two dozen lithe bodies in hooded jackets painted blue, white, and red as a kind of vaguely nationalistic horizon line. As the cluster gathers speed, they scatter and dovetail, darting like birds or bottle rockets into the square, as the image burns to white. The wall text for the piece describes the ambiguity of the action, explaining that the figures could be read as either leftist anarchists or followers of the rightwing “Golden Dawn” faction (as indicated in the title). There is something nostalgic not only about the quality of the video, but about the smallness and unresolved nature of what is recorded. While the work can be fashioned as a banner for a politicized group exhibition, as it is here (and as was the somewhat reminiscent 2007 breakout video by Cyprian Gaillard, Desniansky Raion, with its interlacing crowds in revolt, featured in the first New Museum Triennial), left alone it would intrinsically resist commodification.

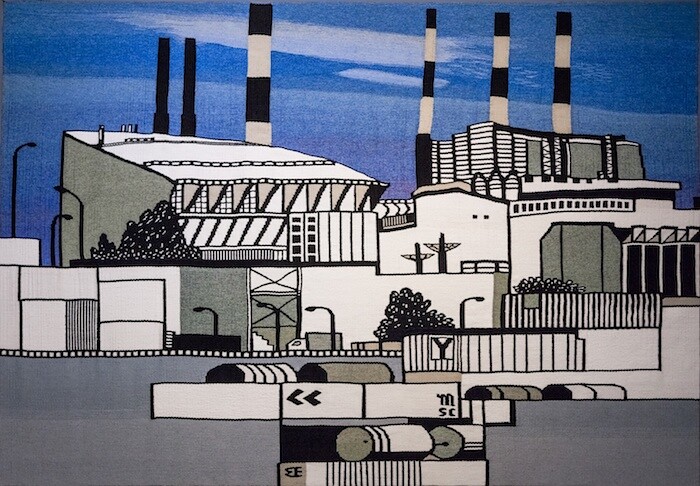

If the fourth floor is a kind of celestial pressure cooker from which revolution is about to erupt, the third floor is a more literal, terrestrial series of works related to industrialization and dehumanization. The most absorbing of Zhenya Machneva’s woven landscapes and still lives of factories and machines is titled Guillotine (2018) and depicts a bandsaw both with hard-edged minimalism and an almost impressionistic irregularity of wear. The pungent hues of Chemu Ng’ok’s portraits, like In Denial (2016) and The Boundary Wall (2017), with their macerated, indistinct faces and runny, tendrilly details claim to tell complex stories about women’s labor in the context of Kenya, although their stylization registers more broadly as having to do with seeing the world as composed of obliterated, expressionistic figures. Wong Ping’s garish, 8-bit inspired Wong Ping’s Fables 1 (2018) projected in a theater around the corner conclude with abstruse, nihilistic aphorisms like “Talent would never go unrecognized, only could people be born in a wrong time. Your time will come when vulgarity and bad taste become trends.” This one could apply to Wong’s video, although the erratic digital nostalgia trend is already late.

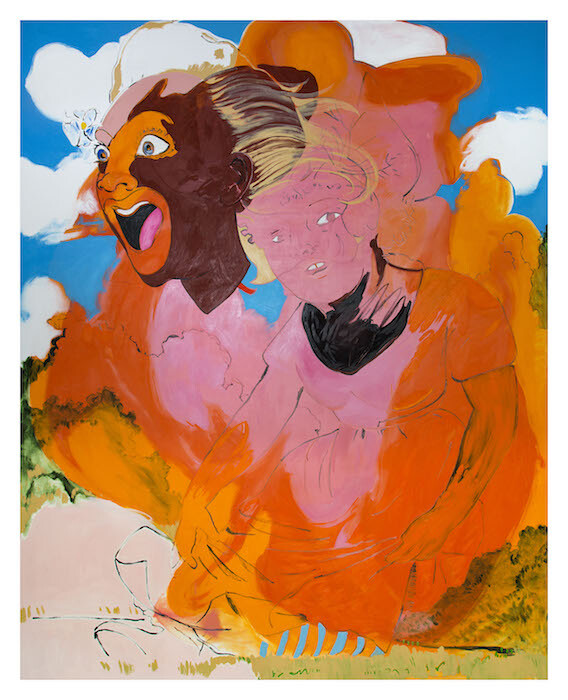

Two standouts on the second floor are painters Janiva Ellis, who juxtaposes antebellum pastoral imagery with hyperbolic cartoonish physical processes, and Manuel Solano, whose poetically malproportioned subjects produce a kind of yearning caught between naivety and wisdom. Both are included in advance packages about the Triennial by Artnet News, “5 Young Stars-in-the-Making from the New Museum’s ‘Songs for Sabotage’ Triennial,” and The New York Times, “Meet Six Disrupters at the New Museum’s Triennial.” Undoubtedly stars in the making, these inclusions are deserved. But as for being disruptors, this preposterous label for artists, transposed from tech venture capital, underlines the self-fulfilling prophecy that is the New Museum Triennial.

Even so, the New Museum is a notoriously difficult space to build exhibitions in, and the fourth floor of the triennial is one of the more memorable tableaux to be contained here. But on the whole, the orchestral quality of the triennial is forgettable: there isn’t a microscopic or macroscopic narrative uniting this exhibition in such a way that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It’s the individual voices that stand out, much as they do in a commercial setting. It is in a rote, responsible way that the show’s internationality should be applauded.

Part of me wonders if I should continue reviewing international group exhibitions when I am so predisposed to be bored and disappointed by them. I consider it my duty to speak out against the convention when given the platform. I don’t know if it’s fair to cast artists as victims and curators as complicit, if often well-intentioned, facilitators who are ultimately either too weak or too disempowered to change how biennials and triennials are done. With a handful of discoveries, this show does its job, but “Songs for Sabotage” doesn’t sabotage the mold of the triennial itself, so in most respects it feels like lip service.