In the early 1960s, Mohamed Melehi was “an immigrant, a lost person” in Minneapolis.1 Later there would be a move to New York and friendship with the likes of Jim Dine and Frank Stella, but at that time the Moroccan artist was a junior teaching assistant at the College of Art and Design and felt like an outsider in the American Midwest. There’s a heaviness to the 1963 acrylic painting that he titled after the city, which opens this exhibition. A block of pitch black pushes down on the monochrome red of the canvas’s bottom half. The colors, included in Marcus Garvey’s pan-African flag and other motifs of left-wing liberatory struggle, hint at Melehi’s politics. He could be hoisting a flag over American territory. Then again, he was never the kind of artist to take make his point so didactically. Ultimately the work remains a painting not a banner: sandwiched in between the red and black is a narrow strip of yellow and grey.

At Tate St. Ives, Minneapolis hangs next to two of the very few figurative works in this survey of the Casablanca Art School, a post-independence generation of teachers and students from the Moroccan institution, where Melehi returned to teach, and who were intent on creating a local modernism. Established by French colonial authorities in the 1920s, the school originally divided students by class and ethnicity, with only western art history taught. In 1962, six years after independence, Farid Belkahia became the director of the school where, alongside his comrades, he revolutionized the curriculum. His Cuba, Si (1961) shows a brown figure, the head cartoonishly enlarged, raising their arms in the air. There’s anger at work, but more disturbing still is Tortures (1961–2), made in response to French atrocities in the Algerian War. A similar figure is shown in oils strung up by a single leg, their tentacular arms limply dragging on the ground.

These are exceptions, however. For the most part, the group channeled their decolonizing mission into formal innovation, taking semi-abstract motifs, patterning, colors, and materials from Moroccan artisan culture and Islamic art history and melding it with references to western-dominated hard-edge painting and post-painterly abstraction. The latter label could be applied to Melehi’s Composition (1968), an oil on canvas in which mirrored parallel waves of rainbow colour undulate across a pink background. Or the painting the artist made a year later, with the same title but in acrylic, in which similar waves of yellow and white meet as a cross. Both works have the bright colors, “linear clarity,” and impersonal brushstrokes that for Clement Greenberg defined the style.2 Yet as is made clear by a display of photographs of Amazigh, or Berber, jewellery taken by Melehi during various trips he made across his country from 1965 onwards, his references—like those of his peers—were far closer to home. The silversmithing he documented is rich in the same zig-zags and undulating parallel lines, the same curves and intricate dances of Berber symbols.

Nearby the curators have lain a rug of the kind common to the souk. One can easily find its typical pattern of diamonds, lines, and borders in a deep red wool, replicated in the simple but striking paintings by Mohammed Chabâa, another teacher at the school, and Mohamed Hamidi. Abdellah El-Hariri’s untitled student work, made around 1965, is a checkerboard whose white squares hold black circles: an evolution of the Berber sign for unity. The tradecraft of the market is even more apparent in Belkahia’s Untitled (1970), a flame motif hammered out of a sheet of wood-mounted slowly oxidising copper, or Anna Draus-Hafid’s Symphonie forestiére, a 1982 tufted wool tapestry. (One of the few female and foreign artists associated with the group, Draus-Hafid was the Polish wife of tutor Mustapha Hafid.) They often favored cheap, easily accessible materials: Ahmed Cherkaoui’s murky blue La Chute de l’étoile (1963) is painted on jute, others on leather (though none in this show, sadly); Melehi would often use car paint.

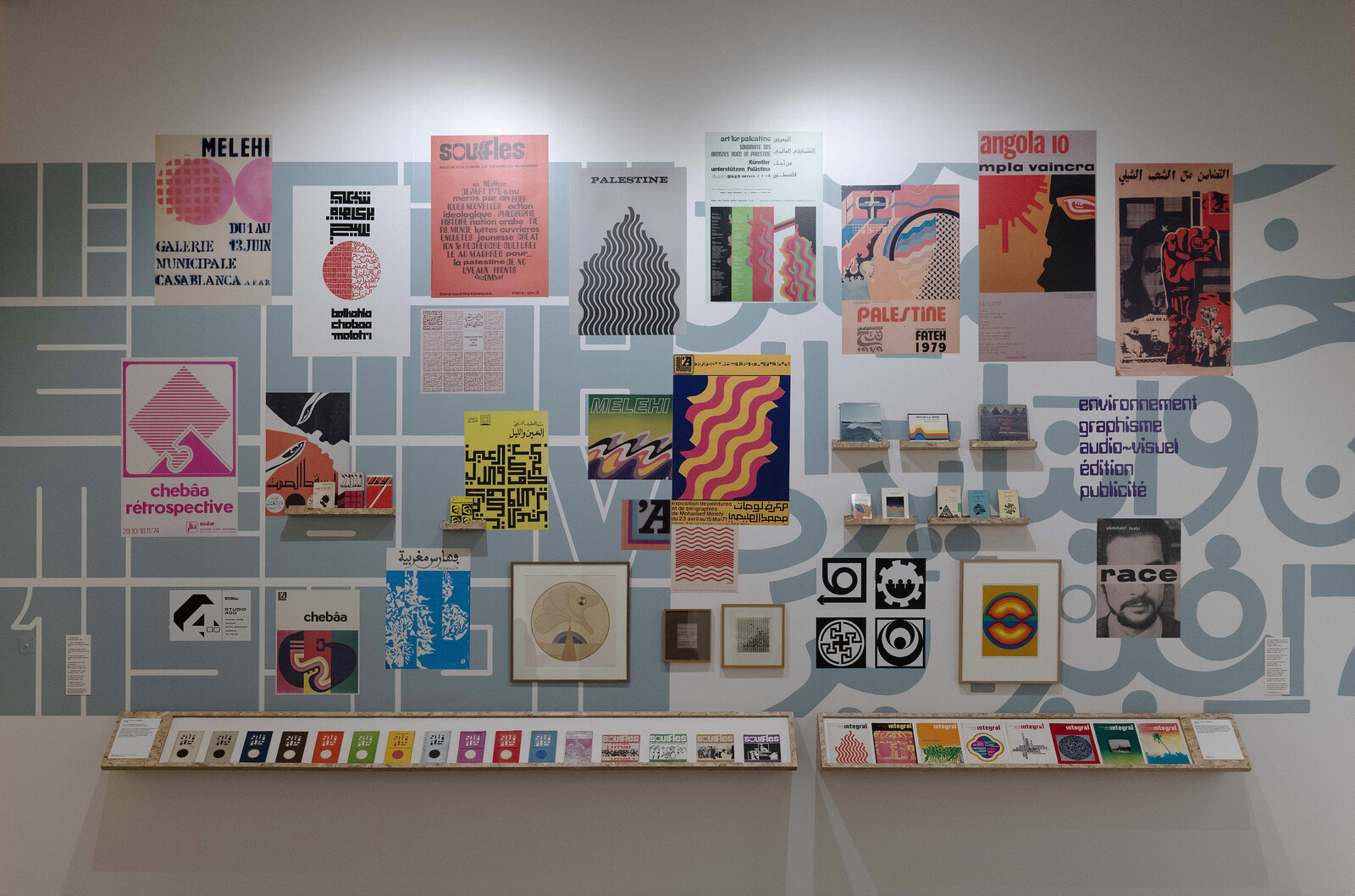

This spirit of independence was a rebuke not just to the old colonial administrations but to American imperialism too—an understandable pushback against the various scholarships the artists had undertaken. Bound up in Cold War diplomacy, Melehi’s Rockefeller funding, for example, was part of a strategy to spread modern “American values” to the developing world—or “to maintain and enlarge the friendly solidarity which unite or should unite all civilized beings,” as an internal document put it.3 Souffles, a Marxist journal for which he and Chabâa became the graphic designers, was probably not the intended outcome. All sixteen issues, from 1967 to 1977, are shown in vitrines alongside a salon hang documenting the group’s numerous experiments in graphic design, architecture, design, and interiors. Among the profiles of figures such as Malcolm X and reports of Palestinian liberation, the journal championed young, poor, or illiterate Moroccan artists. Chaïbia Talal was one: dismissed as “naive” under the previous administration, her work concludes the show. La cérémonie du mariage (1983), a large painting, proves the old order resolutely wrong. The complex interplay of figuration and abstraction conjures a wild party from the canvas with brilliance.

The Casablanca School sought to cleanse Moroccan art of European dead wood by an embrace of pedagogy alongside a forceful use of color and form. In expropriating what western culture might prove useful to its aims, and applying what traditional methods were at hand, the curriculum was an act of resistance against both parochialism and the beige, frictionless, capitalist internationalism that characterized much of the art that came before, and indeed since.

“Mohamed Melehi in conversation with Morad Montazami,” Third Text (February 12, 2021), http://thirdtext.org/melehi-montazami.

Clement Greenberg, “Post Painterly Abstraction” available online: http://www.kennethlochhead.com/greenberg.html.

See Renata Nowaczewska, “American Private Foundations and Reinforcement of Democracy in Cold War Europe, 1945-1968: Rockefeller Foundation as the Case Study,” (2012) accessible online: https://www.issuelab.org/resources/27763/27763.pdf.