When the nymph Daphne refused Apollo’s advances, the god’s patience ran out quickly. “This is the way a sheep runs from the wolf […] everything flies from its foes, but it is love that is driving me to follow you!”1 Daphne took the only means of escape available to her: she prayed for transformation into a laurel tree. Apollo nonetheless claimed her as “my tree,” and so the laurel wreath became an emblem of power worn by royalty, gods, and victors in competition. It is also a symbol closely associated with the Medici family, patrons of the very first opera, most of the music from which has been lost: Ottavio Rinuccini and Jacopo Peri’s La Dafne, performed at the Palazzo Corsi in 1598.

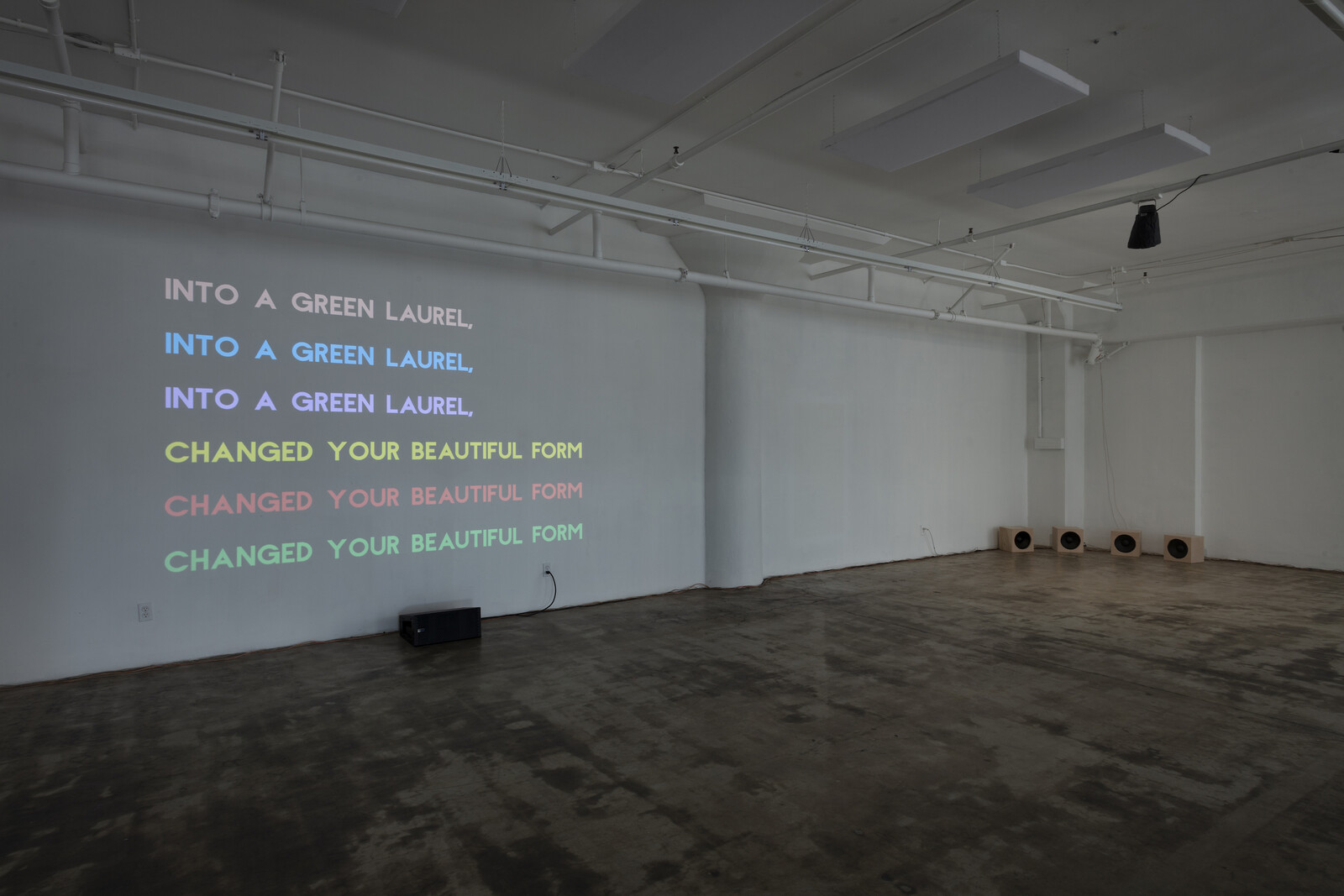

Nour Mobarak’s sound installation Dafne Phono (2022) takes the myth to its acoustic limits, playing a new composition based on La Dafne through sixteen channels into a spare, industrial loft on a street in downtown Los Angeles that still bustles at sundown. Mobarak’s version is sung in six languages that collectively cover the widest possible phonetic ground: the original Italian, Abkhaz, San Juan Quiahije Eastern Chatino, Silbo Gomero, and Taa (West !Xoon dialect), as well as Ovid’s native Latin. Raw blonde wood cubes, each modestly housing a single speaker, are scattered around the corners, the concrete floor, and the ceiling pipes of the gallery. The stage consists of a wall projection of the lyrics in six lines, each one a word-for-word translation into English from the work’s six discrete languages, which were first translated for meaning from the original Italian libretto. Rendered in cheerfully blunt sans serif text, the lines move down the column in a rainbow cascade. A single pine block bench serves as the theater.

One of Mobarak’s most frequent collaborators, in her previous work, was her father Jean Mobarak. In the dialogues between them that constitute her 2019 album Father Fugue, he moves freely between Arabic, French, English, and Italian. His neurological status limits conversation to brief moments—thirty seconds at a time—recordings of which challenge our understanding of connection, history, imagination. His words are sounds; auditory occurrences for speaker or listener. Just as the elementary, stripped scenography in Mobarak’s exhibition at JOAN divests opera of its Baroque melodrama and august mythology, so the linguistic limits set by Dafne Phono cleave words from their meaning (unless you speak all of the languages used in the work). We can vaguely recognize sounds and speech patterns when sitting on the bench, but might not be able to clearly identify any that are “ours.”

The Florentine Camerata, a Renaissance circle of artists who experimented with classical Greek tragedy and incorporated the Tuscan dialect of the likes of Dante, pushed for monodic singing, against the times’ preference for polyphonic music. Recitar cantando, or speaking while singing, came from this tradition, giving us intelligible lyrics and speech within melody. Listening to Dafne Phono lets us receive this type of performance through the barriers of linguistic incomprehension. We might enact these performances ourselves in the act of chanting: whether or not we understand the literal sense of what we are saying, the noise moves through the same circuits.

The intention behind vocalizing a mantra is not to derive straightforward meaning but to create, and enter, a physical experience. In yogic traditions, Om is considered to be the universal sound repeated constantly, with feeling, engaging the throat and opening the heart.2 The Islamic Moroccan and West African traditions of Gnawa song entrance the singer as much as the listener; the votive hymns sung in Latin mass and the repetition of devotional words in Sanskrit serve to heighten spiritual experience. The effect is intensified when, as in Dafne Phono, they are sung en masse.

Ovid, “The Metamorphoses,” trans. A. S. Kline, Poetry in Translation, https://www.poetryintranslation.com/PITBR/Latin/Metamorph.php book 1, lines 504-524

1.28 Tajjapah tadarthabhavanam, The Yoga Sutras of Patañjali.