September 4–December 5, 2021

In recent years, the common description of Brazil as a “polarized” country has shaped a national identity forged in resentment, which only fuels the fantasy that two equally radical factions are in dispute and that one must be annihilated. The 34th Bienal de São Paulo marks an attempt to avert this dystopia, guided by echoes from a distant or recent past. The result is an exhibition that is more reflective than activist, that sets out to listen rather than make claims. It seeks to bring about a meeting between ancestral and contemporary voices, creating a space for dialogue where each can be heard.

The show—curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti, alongside Paulo Miyada, Ruth Estévez, Francesco Stocchi, and Carla Zaccagnini—opens with the Santa Luiza meteorite, discovered in Goiás in 1921. This survivor of the 2018 fire that gutted the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro (and other cosmic misfortunes) makes a strong opening statement about the ruinous state of the underfunded cultural sector in Brazil (echoed, through the exhibition architecture, by dominant shades of black that conjure an atmosphere of mourning). Contemplation of the object is interrupted by the tinkle and flash of metal pieces being transformed by a hired grinder into makeshift knives, an illicit craft perfected by violent prisoners, as part of Paulo Nazareth’s eerie installation-performance Levante/Amolador de facas [Levante/Sharpener of Knives] (2021).

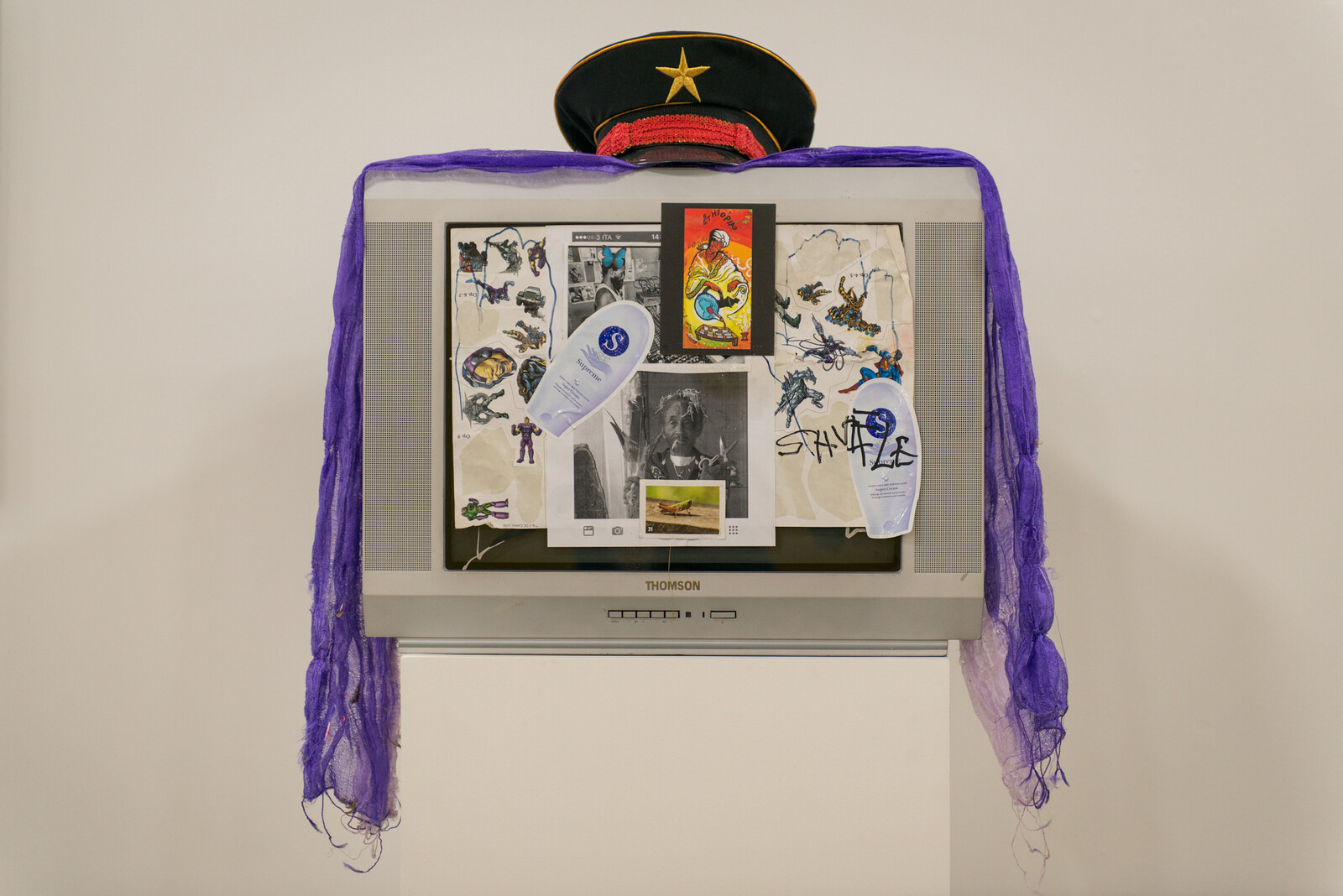

After this sinister prologue, the exhibition slows down and sobers up: there is little further room for spectacle. Most of the more than 1,000 works by ninety artists on display here demand intimacy, focus, and presence. The highlight of the Ciccillo Matarazzo Pavilion’s central atrium is the installation deposição/deposition (2020) by Daniel de Paula, in collaboration with Marissa Lee Benedict and David Rueter. This anti-monumental work takes the form of a platform composed from fractured and worn-out wooden bleachers, which serve as a public stage for scheduled meetings or even rest. These forms once comprised the Chicago Board of Trade trading pit for the grain business, discarded after all transactions began to take place digitally and acquired by the artist for a dollar. Arjan Martins, best known for his maritime paintings, has installed a huge anchor tied by ropes that triangulate the air, as if joining the ends of coastlines separated by the Kalunga that is the Atlantic.1 By invoking the diaspora, the work helps draw connections between artists such as the Angolan painter “Mestre” Paulo Kapela, who dedicated his life to work that recognized sacredness in the profane, Lee “Scratch” Perry (1936-2021) and the highly elaborate plastic language that he developed alongside his music, and Deana Lawson, represented here by newly commissioned photographic work exploring the African community in Salvador.

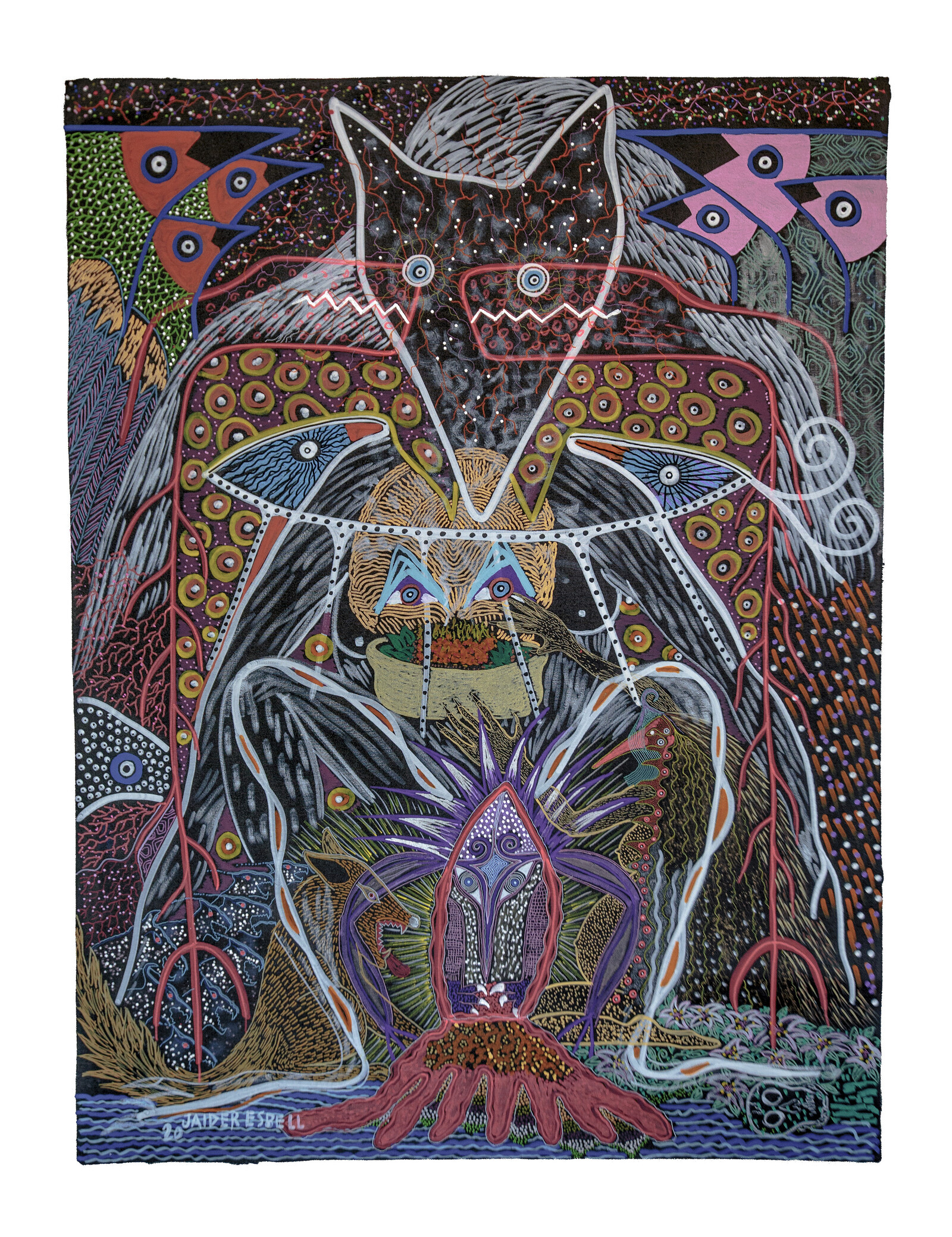

If the Bienals de São Paulo have historically been given nicknames—”Picasso” (1953), “Boycott” (1969), “Vazio” (2008), for example—the day before the opening this one was claimed, by Jaider Esbell, as the “Indigenous Biennial.” One of the key figures in this Bienal, Esbell’s work over the last few years in northern Brazil has been fundamental in articulating the Contemporary Indigenous Art movement: a program for the visibility of Indigenous art that is simultaneously aesthetic, spiritual, and political. In the context of ongoing invasions of Indigenous territories under the present far-right government, the biennial has sought once again to provide significant space to Indigenous artists, a commitment undercut by the lack of representation of Indigenous or Black researchers on the curatorial team. Nor is the power held by one of the longest-running biennials in the world a subject of much reflection or critique, with the notable exception of Andrea Fraser’s performance-video Reporting from São Paulo, I’m from the United States (1998), originally commissioned for the celebrated “Bienal da Antropofagia.”

Instead, on the institution’s seventieth anniversary, the curators revisit a number of historical works that resonate in the present, including several made under the military dictatorship that lasted from 1964 to 1985. These include A carga [Cargo], an enigmatic installation by Carmela Gross first shown in 1969. That year marked the “coup within the coup,” during which persecution of the regime’s opponents intensified (the same expression has been applied to the impeachment of President Dilma Rousseff in 2016 and the current government under Jair Bolsonaro). A ronda da morte [The Death Watch] (1979) is a “parangolé-área” by Hélio Oiticica that has never been performed. Outraged at the oppression in Brazil, he designed a large black circus tent to be filled with lights and music; as the festivities unfolded inside, its perimeter would be circled by menacing men on horseback. The work was scheduled to open the 34th Bienal last year; after the lockdowns made this impossible, it is represented here by wall text and draft sketches from the artist’s notebooks. The compromise serves as a reminder of the lurking Covid-19 pandemic, and of the ongoing threat to Brazilian democracy. The Bienal proposes places of listening and contemplation, yet in a country increasingly robbed, subjugated, and violent, this strategy—and the opacity of the central conceptual vision—feels insufficient. It’s one thing to listen and hope, another to take meaningful action.

Kalunga was a term used by enslaved Africans in the colonial period to refer to the ocean. Today, in Afro-Brazilian cultures, it can also mean “cemetery”.