I am trying not to be cynical, I remind myself repeatedly, humming the words in a little song as I tour the exhibitions of the third edition of Bergen Assembly (BA). I am here to evaluate: the scanning and searching of that state makes this instinctual mental cold critique harder to quiet. This is not a biennial press junket kind of cynicism. Rather, this is something a little more desperate: the cynicism of repeated missed opportunities (and wasted resources) by those we sympathize with. Despite good intentions, these failures to reach; these failures to communicate.

Though similar in some ways—it is a large-scale, location-based, regularly occurring (triennial) art event—Bergen Assembly is not a traditional biennial. The initiative launched a decade ago, during the Bergen Biennial Conference, as a response to the global proliferation of biennials, and for the city to produce a show that would attract cultural capital without rehearsing the tokenisms and clichés of biennial culture: its artistic teams are given more agency to work with timing and format, and this has led to an emphasis on pedagogy, long-term projects, community engagement, and gatherings. The term “assembly” itself suggests a gathering, rather than, say, a show.

Titled “Actually, the Dead Are Not Dead,” this edition is convened by Hans D. Christ and Iris Dressler and organized with a group of 10 core agents. Its stated themes are critical, but broad and too sweeping to be legible: a reevaluation of what it means to be living; a consciousness of past, present, and future injustices; and an invocation that those unjustly killed are still alive. Divided into four nodes, the Assembly includes exhibitions and events in several locations throughout the city, including a cafe, meeting, and event space called Belgin, which the BA team optimistically refers to in the guidebook as “a public space in the centre of the city open to the different communities of Bergen,” where it invites members of the city to propose their own gatherings,1 and an edition of “The Parliament of Bodies,” the extensive, intersectional-politics-oriented program that launched at Documenta 14 in Athens, and which continues here over several months. The last component is a sizable education program, including an ongoing workshop in expanded forms of mapmaking related to participants’ experience of the exhibitions, and walking tours that reconsider the histories of Bergen’s landmarks.

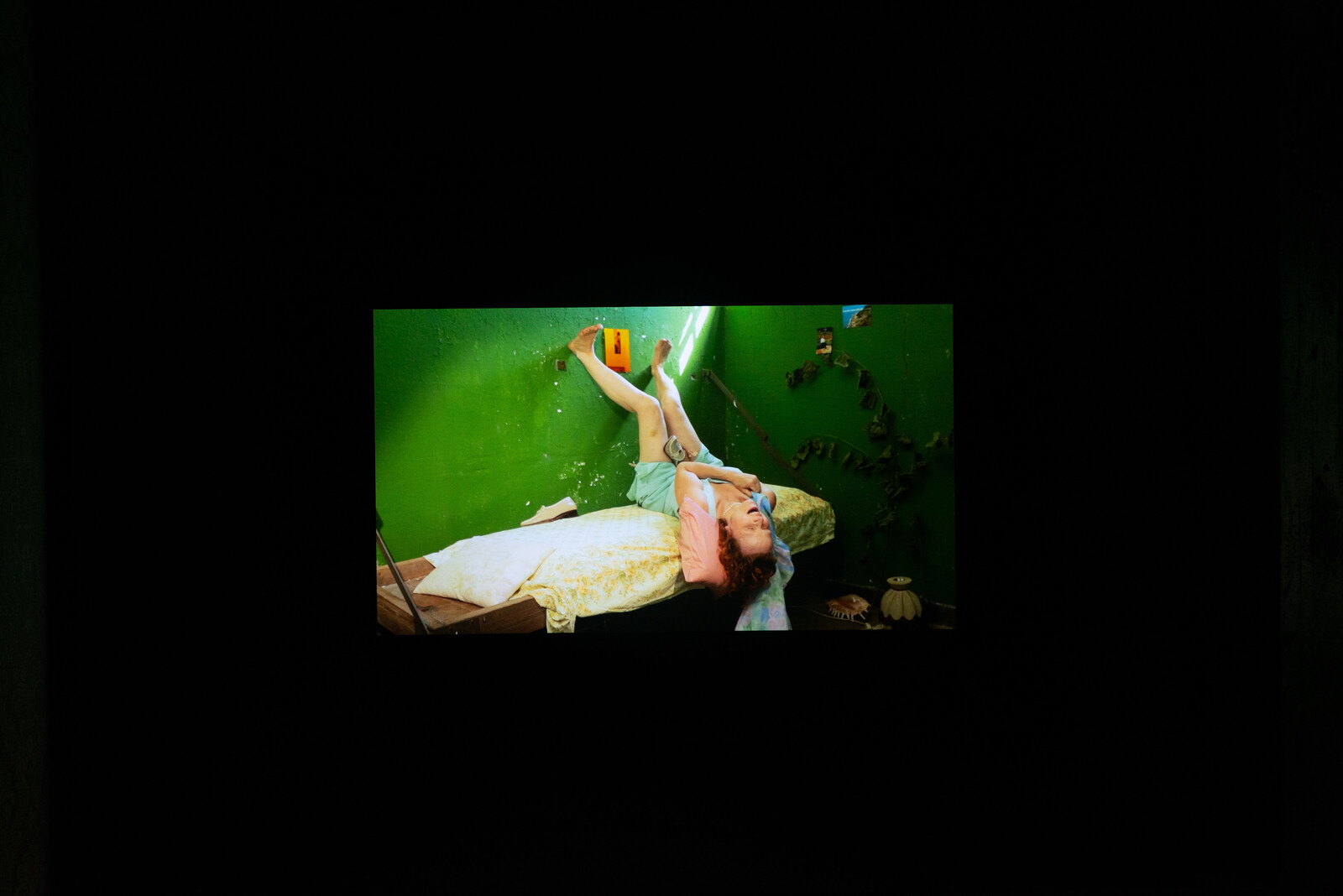

Exhibitions are a substantial element of the project, stretching across the city center, including at Bergen’s Kunsthall, KODE Art Museum, Hordaland Kunstsenter, gallery Entreé, Bergen Kjøtt, and a few small public interventions. The many works on view all track in some way to the heavy critical politics of this edition’s premise. While each space has its own thematic topic, there is an underlying critical core, with dozens of takes on corruption, oppression, and dispossession, from on-the-job deaths in Turkey (with a documentary installation by the group Workers’ Families Seeking Justice) to labor struggles and corruption in South Korea (depicted in photographs by Suntag Noh); the marginalization of the Sami indigenous population in Norway in the social project Moratorium Office: advisory service for decolonialist self-determination (2018) and community artwork and photographic series Rájácummá – Kiss From the Border (2017–18) by Niillas Holmberg, Jenni Laiti, and Outi Pieski; a video about the struggle for Sami autonomy, Apology (2014), by Siri Hermansen; and multple forms of objectification and disempowerment of women, queer, and crip people all over the world. Many of the works included are recommendable on their own—Lorenza Böttner’s paintings, which I first had the chance to see at Documenta 14, are utterly captivating almost no matter the context and Pauline Curnier Jardin’s video Qu’un sang impur [Only an Impure Blood] (2019) is a stunning, wild ensemble of aged women’s bodies. But the highlights are undone by the assemblage. Although there are around 100 artists represented all in all, something suggests to me that either the exhibitions were obligatory afterthoughts for the organizers or far too many curatorial voices were speaking at once. In many cases, the wall texts display vague associations to the works, as though it was uncertain what the final piece would actually look like. This edition of Bergen Assembly took a conscious stance against commissions, so unless I’m missing something—probably something about budgets: I know that is cynical—the wall labels should not have been a problem. While this might register as a petty complaint, with such content-heavy and history-laden material, it’s alienating to look at a work, then back at the text, and not be able to form a productive relation.

With the exception of a special exhibition organized by artists María García and Pedro G. Romero in KODE 1’s “Cabinet,” which takes a retrospective look at political assembly and art through the Situationists, artists of the Spanish Civil War, and struggles of the Roma, the installations are sparely designed. Especially in the main exhibitions at KODE 1 and Bergen Kunsthall, the works sit together with little energy between them, little connection outside of introductory mediations that group them according to a particular politics of resistance. This is especially galling in the case of the exhibition at KODE 1, whose thesis is no less than a proposition for “the dissolution of one of the institutions par excellence that ensure the dead do not return to demand justice: the museum.”2 Instead of dealing with this proposal head-on, the exhibition presents so many works that it comes off as a series of footnotes to a catalogue of struggle. A procession of works about social ills that reads like a museological approach to critique, it felt dead.

To be fair, this festival of gloom vibe was mostly limited to the exhibitions. Several of the live performances over the opening days were full of raw, fun, and energetic moments, even as they were bound with agitprop. I was deeply inspired, for example, by the marathon event of “The Parliament of Bodies,” which included over nine hours of talks, performances, and audiovisual presentations buoyed by expressions of humor, anger, solidarity, and care. Another spark appeared in the restaged, resurrected Aire del Mar [Sea Air] (1988–94/2019), a multimedia performance by late New Zealand artist Darcy Lange and his partner and collaborator Maria Snijders.

Lange’s “audiovisual environmental opera” had been performed with different collaborators and in various versions over the 1980s and ’90s. In this version, flamenco dance and guitar play over, and in relation to, a series of screens depicting moving and still images. The footage features documentary material about pollution and the destruction of the livelihood of Maori people, archival footage of mushroom clouds, and scenes from a flamenco demonstration. The visual juxtaposition of these images was intended to connect the struggles of the Roma—who are credited with contributing significantly to the development and continuity of flamenco—with the indigenous people of New Zealand. With its live accompaniment of singing, guitar, and dancing, the event struck me as a lively counterposition to the exhibition just outside of it. The wildly unexpected combination of nuclear war, expanded cinema, and flamenco had a hypnotic and cathartic effect. It came across as out of place in a museum, which felt right. Here, a single work encompasses all of these ostensibly disparate elements and in doing so exudes a feeling of artistic freedom and political possibility, and shines a light on some of the strategy and sensibility missing from the exhibition surrounding it. The performance’s 1980s rage and hopefulness was an injection of the kind of energy that is endemic to effective movement.

Elsewhere in the guidebook, it is stated about Belgin: “In all its possible and impossible potentials, this space-in-progress will become what its diverse users make of it.”

Bergen Assembly, “Actually, the Dead Are Not Dead,” exhibition guidebook, 77.