In Shirley Jackson’s allegorical short story “The Lottery” (1948), villagers gather for a game of chance in which they draw slips of paper, all blank but one, from an old black box. Children, adults, and elders alike, accustomed to the tradition, participate with a mixture of anticipation and boredom. The ending reveals that the prize, known to them all along, is the stoning of an unlucky villager. Mit Jai Inn’s first US solo exhibition also features a large quantity of “stones” and a lottery that, in subtler ways, uncovers a set of human behaviors integral to the functioning of society and politics. Here, the Chiang Mai-based artist, whose work is often framed as a form of social practice infused with Buddhist teachings, sets up a participatory piece titled after a recent sculpture series, Marking Stones (2022). Visitors are invited to submit pledges for “positive action” for a chance to win one of these sculptures.

The title of the series is a tenuous reference to the bai sema stones used by Buddhist communities in Southeast Asia to mark their territory: the sculptures are, in fact, fully functional baskets, lamps, and stools. Around two dozen of these candy-colored wares occupy a room near the gallery’s entrance. Their shapes are irregular, their surfaces textured, crafted as they were from acrylic-painted papier-mâché. The trichromatic baskets are stacked on a table, along a wall ledge, and on the floor. The lamps, separately titled Marking Lights (2022), are spindly armatures built up with paper pulp and paint and crowned by bare bulbs. The stools, somewhat biomorphic with their spunky, curved legs, exude the most personality. In contrast, a standard metal lockbox and memo pad sit solemnly on a corner pedestal with a ballpoint pen chained to it.

The disjunction between the color-block baskets and their intricately carved, leaf-shaped referent arises, in part, from the fact that the lottery piece at Silverlens revisits a concept previously realized in “Dreamday,” Mit’s 2022–23 exhibition at Jim Thompson Art Center, in the Thai capital, where the work was more fittingly titled Bangkok Apartments (2022). In the earlier exhibition, seventy-four papier-mâché housewares were given away to visitors in exchange for “opening their own homes to the public.” The dispersal of Mit’s objects theoretically expanded the field of the exhibition, allowing it to reach a wider public. In its New York iteration, the specificity and communal spirit of the piece are downplayed. In a way, entering the lottery at Silverlens—as performative as it may feel in light of the rarefied curatorial framework—elicits longer, more sustained engagement than the works on view do. The impossibility of knowing what others have pledged makes the lockbox, with all its mysterious contents, the most fascinating object in the room. This seems intentional: the exhibition does not allow participants to simply delight in the quaintness of a game of chance. After all, one should care what the prize is.

Like the Jackson story, Mit’s exhibition comes with a twist: his whimsical works carry the invisible weight of Thailand’s political history. The artist, a vocal critic and activist in Thailand, where one must constantly navigate censorship, encodes his seemingly innocuous paintings, sculptures, installations, and participatory works with his views on topics as varied as the Chakri Dynasty’s abusive lèse-majesté laws, capitalism, religion, and the artworld itself. Like his contemporary and occasional collaborator, Rirkrit Tiravanija, Mit’s interests lie in the thick of social relationships and in the way forms of power—social, spiritual, economic, and political—are processed through objects.

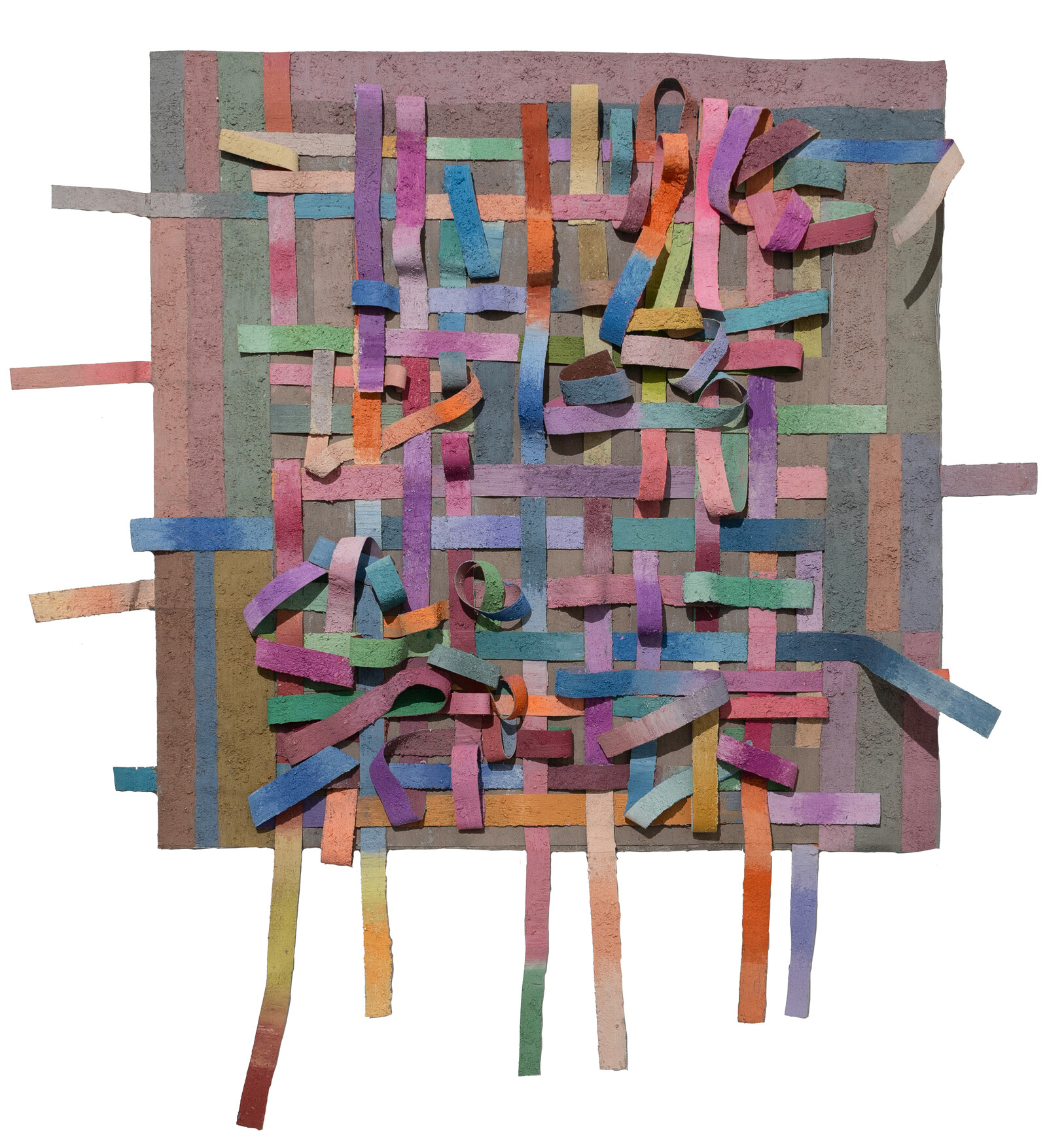

However, while Tiravanija’s works tend to be literal—visitors served pad thai or Turkish coffee are not explicitly asked to reflect on systems of meaning beyond those at hand—Mit’s often perform one or more metonymic functions. For example, Tunnel (2023), a twenty-four-foot installation consisting of strips of canvas layered with thickly impastoed oil, hangs like a trellis-covered walkway wide enough for a single visitor to traverse at a time. The contrast of the work’s black and gold-speckled exterior against its dim but polychromatic interior points subtly to the division between Thailand’s extravagant ruling family and the scrappy, folkish masses living in its shadow. Four untitled paintings made in 2004 feature polygonal color fields that call to mind aerial views of rice paddies but are also intended to reference the patched-up robes of Buddhist monks. Three free-standing spiral sculptures just inside the gallery’s entrance and visible from the street imbue Minimalist forms with the patterns and textures of woven fabrics. Beyond this visual similitude are yet more references—to eleventh-century thangka paintings depicting the life of the Buddha, which are preserved as unframed scrolls, and to the stately, meditating figure of the Buddha himself.

By offering a multitude of nested meanings and unraveling codes, Mit’s exhibition at Silverlens shrewdly conveys the surprisingly similar ways in which karma, power, and knowledge operate. At times, these intangible forces circulate in formal spaces demarcated by ritual and symbolism. Occasionally, they ferment and shapeshift in the dark. Now and then, when treated as ends in themselves, they expose the thrill of accumulation and the obscurity of our reward systems.