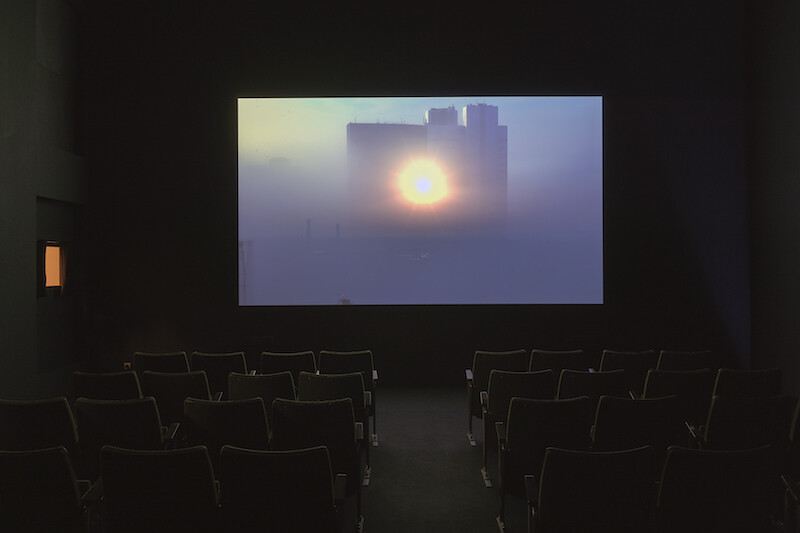

A cloud of stale smoke still hangs in the air the day after the opening of Daniel Pflumm’s exhibition at Galerie Neu, a throwback to another time—15 years ago, perhaps, when Pflumm had his last show at his hometown gallery and smoking indoors was still the norm. This new exhibition not only recalls the 1990s techno scene from which Pflumm’s work emerged, but also an ambivalence toward the art-world context in which it came to find itself. The commercial gallery trappings have been removed: reception desk and gallery assistant replaced by a shiny metal clothes rack with a sign, red on white, reading “SPECIAL” and two mirrors framed on the wall. Inside, the gallery has been transformed into an intimate cinematheque, with GDR-era folding chairs and portable metal ashtrays. Two dark windows offering clandestine views back into the reception reveal those mirrors to be two-way glass. Pflumm’s two new video works have all the harsh relentlessness of his early ones: as sharply edited as they are critical.

While in Pflumm’s previous videos, content was usually derived from, and shown on, a TV screen, the main work here, Hallo TV – FFM (2019), is a luxuriously large projection in the cinema/gallery that takes the viewers outdoors to the cityscape of Frankfurt. An hour-long portrait, its slow-moving passages are powered by a minimal, bass-driven soundtrack, while a series of fixed-frame shots offer high-rises bathed in golden sun, or reflecting glinting silver clouds. Broad, still shots lock on to gridded facades that have all the regularity of Bauhaus textiles: modernism in its purest form put to use. The corporate sublime.

The film begins with dawn mist and a deep, persistent, low bass rumble that accrues ambient, synthetic intensity. The viewpoint is unusually high throughout: it looks straight at the buildings’ top floors, as if it were the eye of the city or its architecture. As light glints on highly polished chrome, or glowing dots of white and red trace the hypnotic reflections of traffic, the human is puny in comparison. There are shades of Godfrey Reggio and Philip Glass’s Koyaanisqatsi (1982), or Frankfurt-based artist Thomas Bayrle’s cardboard motorway convolutes. The city appears as a dense congregation of grids and shiny surfaces: vast aquariums in which miniature humans in white shirts and dark trousers go about their business, sealed in by layers of refraction. Only one scene is shown from the inside: an empty office floor, irregularly illuminated by a white strobe light, offering glimpses onto abandoned hunks of office furniture that populate this surrogate dance floor.

“Nightlife is the opposite of Daylife,” wrote Pflumm in 2016. “It used to be a getaway from everyday hell. Today the clubs are almost there: a continuation of a functional, veneered and conventional world-cultivating isolation and accumulation rather than togetherness and substance.”1 These images of Frankfurt’s architecture, shot at sunrise and sunset, depict the flipside: a daylife that happens even after dark. The borders between private and professional time, work and consumption, have dissolved into a 24/7 illuminated glare. Pflumm handles the glossy surfaces of these buildings in the same way that he used logos in the 1990s: they are amplified but evacuated, abstracted to become pure, seductive, gorgeous surface. By removing the perspective of the individual and relinquishing the need for commentary, they become wordless critiques, articulated in the language of the very thing they question.

Is there something nostalgic to the “us versus them” that these works propose: a time when “they” were still external, identified by a brightly colored corporate logo? Is this disenchantment of a kind that predates smartphones and the internet-saturated social mind? Though Hallo TV – FFM is shot in Frankfurt, it speaks of Berlin too, and the radical facelift it has undergone in the last 15 years or so. Its shabby patchwork of affordable buildings and intermittent gaps of unbuilt wasteland has gone in a real estate grab that saw parcels of land sold off hastily to the highest bidder. Now that the cranes evacuate the skyline, we are left with static rows of opportunistic architecture, cheap and unremarkable, among which we are supposed to live. The city’s potential was sold off too in this race toward development. What we face, and what Pflumm’s work captures, is not so much nostalgia as wholesale disillusion.

Back in the gallery’s entrance room, a wall-mounted flat screen plays another new video, Kindercountry (2019), which picks up where earlier works left off. A tightly edited composite of TV clips, it switches hypnotically, beat by beat, from glossy liquids to luscious creams; explosions-crashes-bullets-shoot ups, or logos-graphics-tag-lines. It has its own internal logic: one of shape, texture, camera angle, close-up, like a stream of advertising-consciousness, thought up by the screen itself. The closest Pflumm comes to direct commentary appears in this work. During a rapid-fire montage of horrifying violence, a superimposed window shows Angela Merkel: a straight-faced witness to these scenes of devastation, she calmly sips a glass of water. Responsibility abnegated, the evacuation is complete.

Daniel Pflumm, “Atmosphere,” Flash Art no. 311 (November–December 2016): 101.