There are differences that make a difference and differences that don’t. The 60th Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, announces its commitment to the ones that don’t with the title: “Foreigners Everywhere.” The phrase comes from a 2004 artwork by Claire Fontaine reprised for the exhibition but, when blown up to biennial scale, the one-liner turns didactic and presumptuous. Any number of approaches could have mitigated against a title that unites the work of 331 artists under a false equivalency (see also: “We Are the World,” “All Lives Matter”).

Pedrosa organizes the show around two broad identity rubrics: “Queer”—a metacategory that includes anyone “who has moved within different sexualities and genders,” along with outsider, folk, and Indigenous artists—and “Foreigner.” In a departure from the Biennale’s usual emphasis on contemporary makers, more than half of the featured artists are deceased. Folkloric, salt-of-the-earth vibes dominate: the mood is wholly at odds with the bland cosmopolitanism at play in terms of who shows up and how the work gets presented.

By the time one encounters the colorful burlap-backed tapestries credited to “Arpilleristas (unidentified Chilean artists)” in the Arsenale group exhibition, you’ll have already come across several superficially similar textiles from around the world. These particular tapestries are a material testament to feminist struggles against Pinochet’s 17-year dictatorship: Women stitched cutouts from the clothing of loved ones (often the disappeared) into scenes depicting life under the US-backed authoritarian regime, then Catholic Church groups helped smuggle these quilts-as-countermemory out of the country, where they were sold in fundraisers. But you wouldn’t learn any of this from the Biennale, whose wall text refers to “embroidered textile artifacts” with scant context.

Stranding arpillerista quilts from the aesthetic and political territory in which their artistic intervention operates reduces their existence to a tightly bracketed category. The curation distances information that would help us to explore any resonances these activist quilts might have with their contemporaries, such as the maritime flags that Nicole Eisenman and Rosalind Nashashibi designed for one of the many anti-genocide/pro-Palestine events during the Biennale’s opening week.

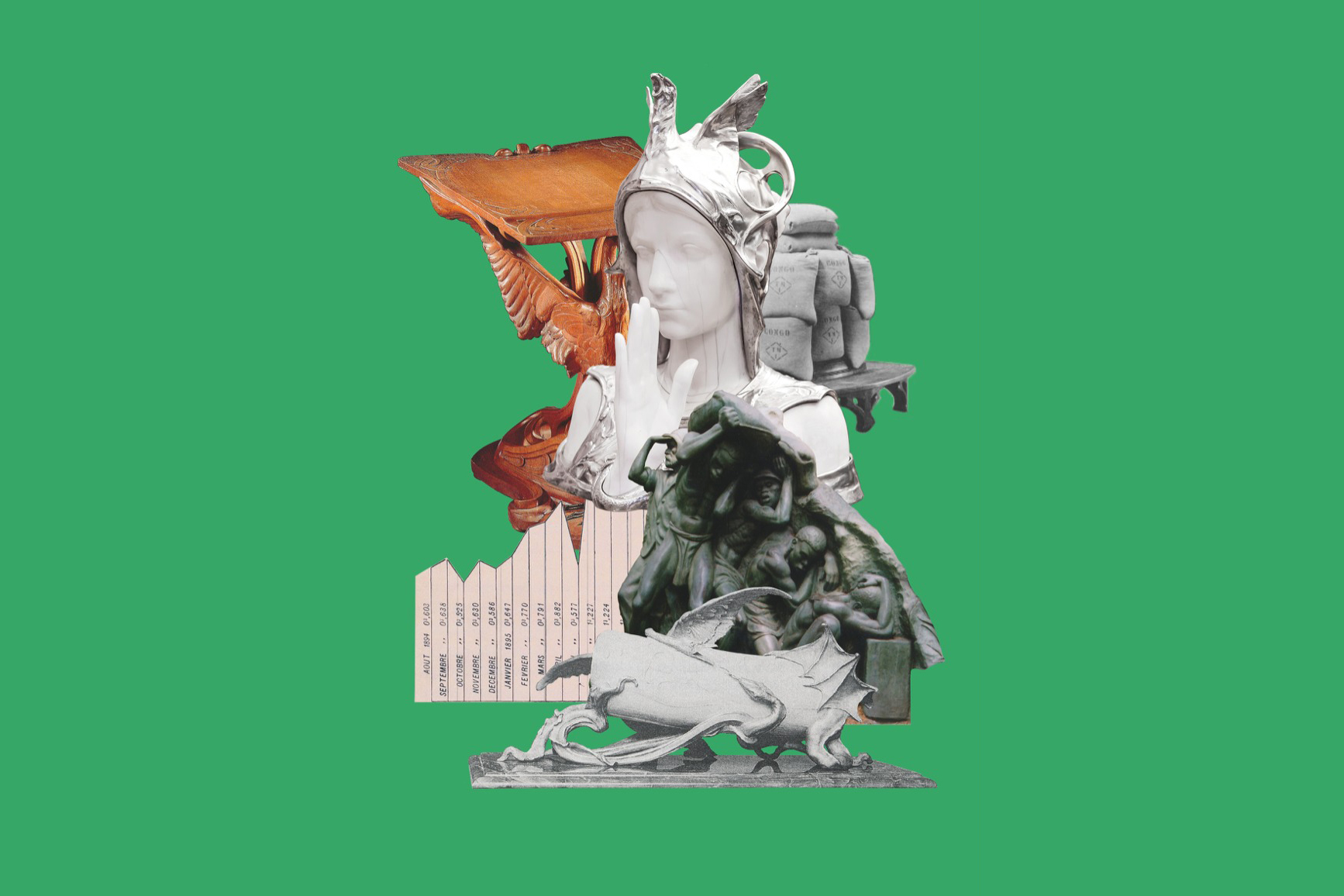

“Migration and decolonization are key themes here,” writes Pedrosa in the introduction, and the Spanish Pavilion epitomizes this thematic approach. In it, Peruvian-born Madrid-based artist Sandra Gamarra Heshiki has created “Migrant Art Gallery,” a mini-museum in which each of five rooms is filled with scale recreations of various colonial-era paintings and drawings, verisimilitudinous except for corrective quotes from contemporary writers rendered in cursive. The entrance gallery, Virgin Land, houses large landscape paintings. A paragraph on the first canvas concludes: “The lush plantations of South America are pictured as if they were created and maintained without the suffering, hard work, and dispossession of Indigenous people.” The Cabinet of Illustrated Racism gallery does similar with scientific drawings, another gallery features captioned botanical illustrations, and so on. The number of works on display is exhaustive—why must immigrants always be seen to work so hard?

By centering its address upon a Euro-American white subject, “Migrant Art Gallery” limits possible conversations and alienates the non-white viewers whose subjectivities its stated intention is to uphold. This is admonishment art. Its fear of ambiguity and embrace of moral instruction helps to maintain a steady emotional-intellectual tone across a wide range of mediums; it’s stable in that way and one soon tires of talking about it.

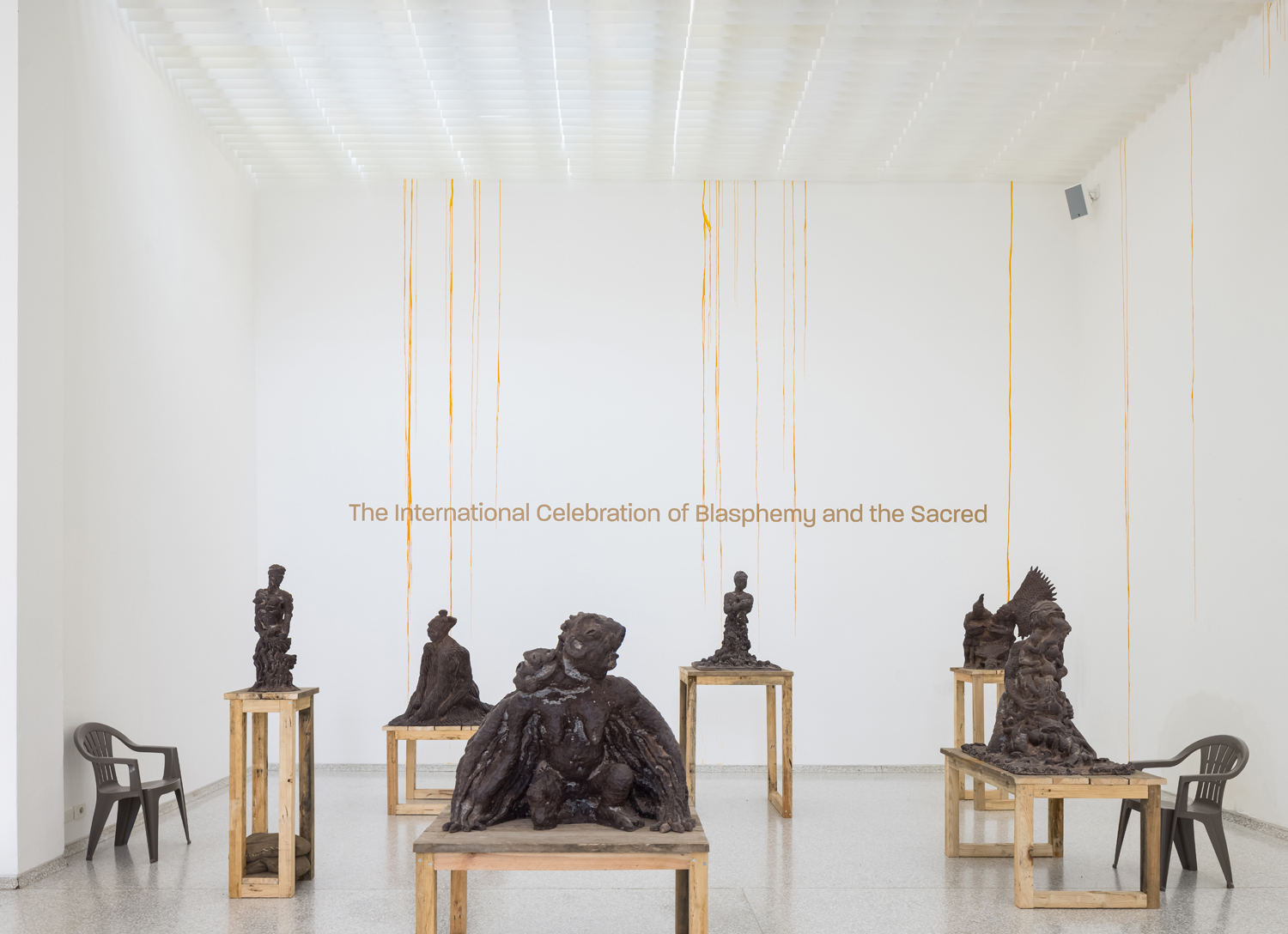

Decolonization is a process, not a theme. The nearby Dutch pavilion takes this up. It features sculptures made by the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League (CATPC) working in association with their “unpaid agent,” Dutch artist Renzo Martens (credited as a collaborator with pavilion curator Hicham Khalidi).1 The figurative statues act like parables that contrast idyllic village life (“Couple of Equality,” “Fish Protector”) with the horrors of colonialism (“Forced Love,” “Money Angel”) and art-market inequity. The objects appear as a by-product of Martens’s extended project of “reverse gentrification,” in which rural Africans make clay sculptures that get recast in cocoa by Martens’s Amsterdam studio. The CATPC buys back forest acreage with profits from any sales. There’s something queasy about it all, in part because its most visible output is discourse about western artworld ethics—not African aesthetics, pointedly. But that’s fine, right?

At the Nigerian Pavilion, sponsored this year by the same global auction-house-cum-luxury-brand as the British Pavilion, curator Aindrea Emelife assembles eight artists into a multilayered group show called “Nigeria Imaginary.” It deploys a variety of exhibition techniques, from a slurred AI video in a hallway prefacing a room of animatronic calabash objects, to playfully mirrored vitrines holding pop-cultural artifacts such as FESTAC ’77 commemorative plates, to Toyin Ojih Odutola’s large, luminous pastel-and-charcoal paintings that stand on a corner platform, hinged like an open book. The panels depict figures in loose relation with each other—do we see leisure, ablution, or ennui?—against semi-geometric backgrounds, every face turned away from the spectator. It is three-dimensional, the curatorial logic that creates space for the viewer to arrive at her own conclusions throughout “Nigeria Imaginary,” and it’s fun. Bonus: free entrance, staged in an off-site palazzo in the comparatively quiet Dorsoduro neighborhood.

The Greek Pavilion provides a welcome dose of underexplained estrangement, both in the context of a biennial that privileges legibility-by-categorization and in our present era of declarative politics. Composer Thanasis Deligiannis and playwright/philologist Yannis Michalopoulos brought together a multidisciplinary crew to create “Xirómero/Dryland,” a brute affective choreography for farm equipment, audio, video, and lighting.2 An enormous piece of agricultural irrigation machinery occupies the pavilion’s center. Periodically it will clunk and rotate a few degrees, as its crane-appendage affixed with a loudspeaker shudders up or down. Every now and again the machine expels water onto the floor. Its acoustic mechanical sounds blend indistinguishably into the (prerecorded) sound design. Less frequently, overhead fluorescents snap on for a few minutes at a time—a reverie disruption like accidentally turning on the lights at a party. Projections and screens are relegated to a supporting role here, in contrast with at least a half-dozen video installations elsewhere in the Biennale, which feature a person of color dancing in colorful clothes against a monochrome background. The sound and auratic presence of “Xirómero/Dryland” destabilize any division between reality and its representations.

Of all the world’s cities, Venice is the one most optimized for instant capture. Sunbeams on water, perfect church, bridge over canal. Whether Tintoretto’s sweeping tumult or shots of what you’re about to eat, you can’t not take a picture. La Serenissima asserts that beauty must be immediate and immediately registered, by camera or pencil or brush. It comes as a rare relief, then, when artists step back from this nearly insurmountable pressure to present. Up by the Arsenale’s wooden rafters, a tear of cowhide rests on horizontal blue ropes. The scale and dimensionality are hard to judge at this height. Many will overlook Rindon Johnson’s For Example, Collect the Water Just to See It Pool There Above Your Head, Don’t Be a Fucking Hero! (2021–ongoing), and even if you do spot the antiheroic installation, distance frustrates viewing-as-knowing. In the Giardini park—one of the few areas where it is comfortable to sit—Johnson has a big, sharp, hugely public sculpture. “Visibility is a trap,” said Foucault in the same breath as he spoke of darkness’s protective power. 3 Put Johnson’s polarities together and you’ve got a battery, an energy source.

See Alice Gregory, “Can an Artists’ Collective in Africa Repair a Colonial Legacy?” in the New Yorker (July 18, 2022): https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/07/25/can-an-artists-collective-in-africa-repair-a-colonial-legacy.

Curated by Panos Giannikopoulos, the Greek Pavilion also features contributions from artists Elia Kalogianni, Yorgos Kyvernitis, Kostas Chaikalis, and Fotis Sagonas, as well as artistic collaborators Fotini Papachristopoulou, Vassiliki-Maria Plavou, and Marios Stamatis.

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, translated by Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1975/1995), 200.