0.

The voice of the Loudreader helps with our separation anxiety. “Time is a colonial construct” she says, “they pay you by the hour so they can own your sense of time.” As we hear her voice reading aloud texts from other times, we think about habitable futures. A conversation between the dead and the yet to be born is happening in the voice of the Loudreader. Loneliness is a collective disease. We are trapped in individual cells, in virtual realities designed just for you. And yet, we are cursed to write about what we hear from our individual perspective, one story among many. Unmaking this world is as important as creating new ones. The voice of the Loudreader does not explain because explaining is a form of ruling. She just tells stories of breakaways, of collectives that defeated loneliness, of worldmakers of the past that conjure other futures. “This world is a bubble” she reads, “put a knife to it.”

1. Books and Catastrophes

In the beginning, there was catastrophe and books. We were fresh from the trauma of Hurricane María in Puerto Rico, a cyclone superpowered by global warming that hit an island already devastated by neoliberal austerity measures and a cruel and criminal debt to Wall Street. Two years later, our families barely recovered from the aftermath, in our exile in Nebraska, catastrophe struck again. We were participating in a seminar on “Decolonial Pedagogies” when massive floods, the product of the rapidly changing temperatures in this age of climate change, inundated a large Latinx community in Fremont, just an hour from the University of Nebraska. Most of the affected were undocumented migrants working in the meat packing industry, who had been living with their families in an exploitative mobile home park owned by a billionaire family. After the floods, FEMA paid the billionaire family, but not the families living there and who lost everything. Our students pushed us to leave the comforts of the university and to learn how to become useful in our age of catastrophe. They also collaborated with us on making an exhibition in Omaha that became the Post-Novis Collective, which featured a revolutionary worldmaking syllabus that became the predecessor of the Loud Readers Trade School.1

A year later, Covid hit, a different kind of catastrophe, on a global scale, that nonetheless revealed the same inequalities that the hurricanes and floods did. We were lonely in our houses. We missed collective learning. Like addicts, we sought our fix in the form of informal Zoom seminars, open to anyone, in which we read aloud for fifteen minutes or so from a book we thought was important to understand our world. We circulated the readings as PDFs beforehand, and we discussed them afterwards in a disorganized yet productive way. We called these gatherings “LOUDREADERS Sessions.” Books and catastrophes, that is the beginning. In those books we read about other worlds. Books became a space for seeking an architecture. Perhaps naively, we thought that books can be a space (among many) not to fix this world, but to imagine and then make, collectively, other worlds.

Following the way that Luisa Capetillo “used” books, it is also necessary to disrespect books, to emancipate ourselves from that damned reverence of the Ivory Tower.2 To revere books is paralyzing. Better to eradicate the “good taste” (so white), to break books into fragments and PDF’s, to strip them, to use them like tools, like a hammer or a table, like building blocks; to not read them alone in silence in our air-conditioned offices, but to read them aloud in the heat with friends as desperate as us, reading together and doing it the “wrong way” according to the standards of the patriarchal and supremacist universities we inhabit. Reading that way, we might recover some agency as “worldmakers,” no longer subjects bowing to the burning world we inherited. “Worldmaking” has become for us an anti-capitalist trade, not a productivist market.

2. Loud and intense

Founded in 2020, the caretakers of the LOUDREADERS Trade School (LRTS) are the architects Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García, but now they are joined by many others around the world. It has been a free and open online venue offering hundreds of “LOUDREADERS seminars” featuring scholars, artists, and architects whose work contributes to a critique of colonial, capitalist, and educational spaces. Inspired by the itinerant work of the Puerto Rican anarcho-feminist activist Luisa Capetillo, who became an international public intellectual while working as a loud-reader in tobacco rolling factories in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and on the East Coast of the US, LRTS seminars track emerging networks of solidarity across the Global South.3 They set a tentative horizon of critical readings the speakers deem essential for a revolutionary imagination in the present. In the summer of 2023, a ten-day in-person LRTS was held at the University of Puerto Rico, featuring workshops with scholars, artists, architects, and designers from the greater Caribbean (including Trinidad, Haiti, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and more) free of cost to anyone interested and able to attend.4 The result was a rare moment of pan-Caribbean intellectual and transdisciplinary collaboration. Although the history of Caribbean countries is inextricably tied, the diverging colonial legacies among the archipelagos have often meant that intellectual dialogue takes place in the North, with our former (or present) colonizers rather than with each other.

The visual aesthetics of LRTS are by now quite recognizable and can be seen in the books, editions, posters, designs, and website.5 From the synergies among the scholars, artists, writers, and researchers that make up LRTS, a handful of books have been published,6 and dozens of on-site symposia, workshops, and exhibitions have taken place in various countries. Through more than one hundred different events, LRTS has created a global reading list of revolutionary books that can assist us in the creation of other futures. Among many other things, LRTS is a sort of itinerant digital and nomadic library of texts that challenges our horizons of political and revolutionary possibilities. Many of the books we share are being shared for the first time across the continents in the Global South and translated into various languages. To the best of the involvement of the author of this piece, there are three fundamental points of departure to the school and what it does. An awareness of these three points is the common ground of the hundreds of collaborators of LRTS:

- Capitalism is entering a vicious world-ending cycle in which ecological catastrophes bring back the worst white supremacist, patriarchal, and anti-migrant ideologies that gave birth to the modern world.

- The already weak institutions that were supposed to contain the most violent racist, patriarchal, and necropolitical impulses of modern capitalism (social institutions, hospitals, schools and universities, welfare states, etc.) are all in crisis in the neoliberal present or at the brink of collapse.

- “Worldmakers” (writers, artists, architects, and engineers, in all their iterations and forms) must radically transform their workshops and learning networks to confront this later stage of capitalism and empire.

Finally, the one writing this text is many. Yet, we, very much involved with LRTS from the beginning, are but one perspective of a multiheaded brain, one that works on fiction and Caribbean imaginaries. Our story of this project is ours, and it is not meant to represent the views of the founders or the many collectives that conform the school. To begin with, we do not believe in representation, only in participation. Our story of the LRTS is not a History, but only one narrative take on the building of something that is constantly changing.

3. The Caribbean and Virtual Realities

The Caribbean islands are at the center of LRTS because it is there that our modern capitalist world was born and is rehearsed. The Caribbean is the origin and center of the world that is now crumbling.7 It is in the Caribbean that the great modern empires rehearsed genocide, slavery, and the bio-control of populations that allowed them to globalize power. The Caribbean is the fractal where we can identify patterns that reproduce within macro-structures—both forms of oppression and forms of rebellion. The three original and cyclical events that characterize modernity, that make modern imperialism and capitalism possible, are all the result of the Caribbean experiment: the dehumanization and genocide of native populations to appropriate natural resources; the enslavement and forced migration of a brutalized work force in plantations; and the control of population through the control of the body of women.8

Islands in general are key strategic geographies for the global expansion of the six white modern empires that globalized markets and dominated the modern world militarily.9 These empires could expand faster by sea than by land, so islands around the world, from the Philippines and Polynesian Islands, from the Canary Islands and the Islands of Cape Verde—but with its center and origin in the Caribbean—become key fortresses and ports to support the imperial enterprise and globalization of their markets. Throughout the modern centuries, we can see the same architectures being built in all these islands around the world; imperial architectures that try to homogenize the landscape of the islands while attempting to erase their indigenous populations. As soon as the forts are built and the inhabitants of the islands are violently pacified by the constant arrival of military ships and cargo, a new homogenizing architecture emerges and repeats through all the six empires’ colonized islands: plantations.

The plantation is a formula of early capitalism that was designed to be imposed over any culture and people, reproducing the same type of exploitation from Sri Lanka to Cuba, from the Philippines to Jamaica, in what many scholars today call the “Plantationocene.”10 The form of the plantation is the fundamental technology and design that births capitalism.11 What plantations produced were perfect capitalist products; products that as soon as they are consumed, like drugs, create more demand for them: tobacco, sugar, and coffee.12 These are agricultural products that will not allow the native populations to sustain life, but will create a global market, a global addiction that keeps slaves and workers dependent on the revenues of their masters.

Through slavery and after it, through government- and corporate-led campaigns of labor displacement, island populations will be moved from one to the other, creating a constant racial mixing and displacement; a forced migration and deterritorialization that is the beginning of the world of migrants we live in today. The Caribbean, where workers from all continents have been imported to work on plantations for over five hundred years is the paradigmatic example of this. The two essential architectures during the centuries of empire and capitalism are forts and plantations. In the past few centuries, the fort and the plantation have evolved into many new forms, but all obey the same principles, from the tourism industry and the innumerable US military bases all over the world to the islands that become tax havens or sites for pharmaceutical, financial, technological, agricultural, and military experimentation.

Capitalism and empire are also utopian worldmaking enterprises. They sell and impose a “paradise” (often presented as an island) with the hidden cost of a brutal necropolitical reality. Even today, the contemporary crypto-billionaires of “Puerto Utopia” speak about the island of Puerto Rico as a paradise in the same exploitative terms that Columbus used centuries ago in the so called, “Letter of the Discovery.”13 From the beginning of the modern project, Caribbean islands are seen in a contradictory light: a promise of paradise disturbed by the savagery of its inhabitants. The legends of El Dorado or the “Fountain of Youth,” even Shakespeare’s The Tempest (often cannibalized as the problematic genesis of Caribbean literature),14 is reproduced today in the language of tourists, investors, and new colonial settlers in their Airbnb’s and the gentrification of our islands’ urban areas and beaches.15

Capitalism and empire depend on selling these immersive architectures and virtual realities: from “all-inclusive” resorts and cruise ships to the metaverse and virtual reality technologies. Modernity is filled with simulacrums, “pretty” immersive realities that hide the ugliness that makes them possible. It is not a coincidence that paranoia is the quintessential modern feeling (already seen in the “enchanting wizards” of Don Quixote, the first modern novel, and in the “evil genies” of Descartes, the first modern Western philosopher). Paranoia, which only emerges as a symptom in modernity, is a visceral rejection of the virtual realities of control that capitalism and empire are selling. Paranoia is one of those “ugly feelings” of modernity and it is inextricably linked to our conception of space.16

It is precisely because the Caribbean has been the origin and continuous site of experimentation for capital and empire that it is where we can find the most unruly and revolutionary cultures against capitalist modernity. The Haitian Revolution (1804) and the Cuban Revolution (1959) still stand today as the most singular and rebellious revolutions against capitalism and imperialism. From Ramón E. Betances and José Martí to Frantz Fanon, from Baron de Vastey to Ché Guevara, from Aimée Cesaire to Luisa Capetillo and Pedro Albizu Campos, Caribbean cultures produce, out of necessity, the most radical intellectual challenges to our political horizons of possibility. A pedagogy of unruliness rehearsing another future, a post-capitalist and anti-colonial future in the center of the most destructive versions of capital and empire, emerges out of catastrophe and destruction.

The Martinique philosopher Édouard Glissant goes so far as to identify Caribbean cultures as a transformative challenge to Western thought. The fundamental idea behind Glissant’s Poetics of Relation is that everything exists in relation to everything else. That is, through the Caribbean experience, we challenge the ontological notion at the center of Western thought that argues that what is, is, and cannot not be; that things can be by themselves, that “I think, therefore I am”; the existence of the mind without the body, of things by themselves without relation, of abstractions without materiality, of virtual paradises without living bodies. Against ontology, we propose relationality; to the modern mania of isolating and individualizing, we propose an archipelagic thinking in the time of collective species.

4. Worldmaking and Wordlessness

Most sessions of LRTS, either online, printed, or on-site, are divided between “loudreading” (sharing books), “destemming” (discussion), and “worldmaking” (creative workshops). Worldmaking comes with most revolutionary potential, but also carries the biggest risk, precisely because both capitalism and empire are also worldmaking forces. To avoid the horror of reproducing what we are critiquing, “loudreading” and “destemming” are fundamental. Two traditions have become a constant reference for LRTS in this regard.

First is the anti-colonial tradition that we could call “the plurality of habitable worlds,” which is based on texts by Capetillo and Subcomandante Marcos.17 In this tradition, we must radically democratize the “factory of worldmaking.” Rather than vertically imposing a world from a position of power, we open the doors of the factory of worldmaking to anyone. We make the factory horizontal. We empower others to make worlds. If the plantation system and military forts were an architecture seeking to homogenize the planet into the one worldview of expanding modern empires that sought to unify the world, these decolonial traditions, in the words of the Zapatistas—the Pan-Maya indigenous peoples in open insurrection against the neoliberal powers—seek to “to create a world where many worlds can fit.”18 It is not a coincidence that global anti-capitalist movements like Occupy Wall Street also adopted this Zapatista slogan, and often described their workshops on radical democracy as “world making sessions.”19

Second is what we could describe as the tradition of “worldlessness,” which we borrow from the philosopher Roland Végsö, which can be loosely identified with the post-structuralist tradition.20 Within this tradition, critique is the primary tool. Through criticism we can burst the illusion of reality that the world has imposed on us like a bubble. Critique here is a social praxis. We can relate to each other and make communities through this act of constantly walking with needles, bursting the bubbles of illusion and the virtual realities of market and empire. A “world” is an imposition; only when we reveal it as a superstition can we live in community. “Being collectively” requires this stage of wordlessness.

We do not believe that these two options (the plurality of worlds or worldlessness) are a binary, nor are they mutually exclusive. We think they are symbiotic. We must do them at the same time: destroy the illusion of the worlds imposed on us and create new ones.

On December 31, 2012, the day the world was supposed to end according to the superficial interpretation of the Mayan calendar, and after one million Indigenous peoples from across Mexico performed a cryptic protest in absolute silence, the Zapatistas published the following short poem:

Can your hear?

It is the sound of your world

collapsing.

It is the sound of ours

resurging21

5. Any space can be turned into a LOUDREADERS Session

A fundamental principle of LRTS is that any space, no matter how exploitative, can be creatively turned into one of emancipatory praxis. Therefore, at the forefront of the project is a desire to revolutionize the space of academia and our departments and schools of architecture, art and the humanities. Sites of destruction, exploitation, war, genocide, occupation, of brutal hierarchies and inequalities, can and should be used, occupied, and appropriated to generate horizontal practices for the collectivization of knowledge.

Take, for instance, Martín Sostre (1923–2015), a Puerto Rican black panther and political prisoner who famously created a “black-Asian” bookstore in Buffalo that sold books about revolutionary struggles around the world and was accused of instigating the city’s black riots of 1968.22 In prison he became a jailhouse lawyer and was able to connect political prisoners of very different struggles from all over the world that otherwise would not know about each other. A true creator of networks of solidarity, Sostre worked from the most exploitative of spaces, a prison, yet was able to create and circulate an entire revolutionary library.

Another example of the unlikely emergence of a revolutionary library, a shared bibliography in the most unlikely places of explotation, can be found in the recent LRTS conversation with Ilan Pappé. According to Pappé, many indigenous struggles in the Americas influenced the Palestinian peoples in their resistance to genocide and ethnic cleansing,23 which has also been influenced by the Zapatista struggle in Chiapas.24 These examples demonstrate the existence of a pedagogy of resistance that travels through networks of solidarity across the planet, connecting far away regions that learn from each other without turning their struggles into formulas that are imposed over diverse populations. They fight against what is common amongst them, but the way to fight is completely different for each. There is no formula to be repeated, but there is a knowledge being shared.

The tools and the toolbox we use to make new worlds are inevitably of this world that has been imposed on all of us. Like Kafka’s ape, we are condemned to use the tools of our masters to build the tunnels out of our cages.25 We must work with what we have in the here and now. We cannot wait for the “perfect conditions” for the revolution. Worlds are not made in a vacuum, but out of the specifities and singularities of each historical and geopolitical reality. This requires us to study when and where we are. Catastrophes teach us that even the most adverse conditions can become laboratories of mutual aid. “Hurricane María was teacher” was said many times by people in the struggle in Puerto Rico.26 Even a prison, solitary confinement, or an exploitative tobacco factory, can be turn into an alternative LOUDREADERS university.

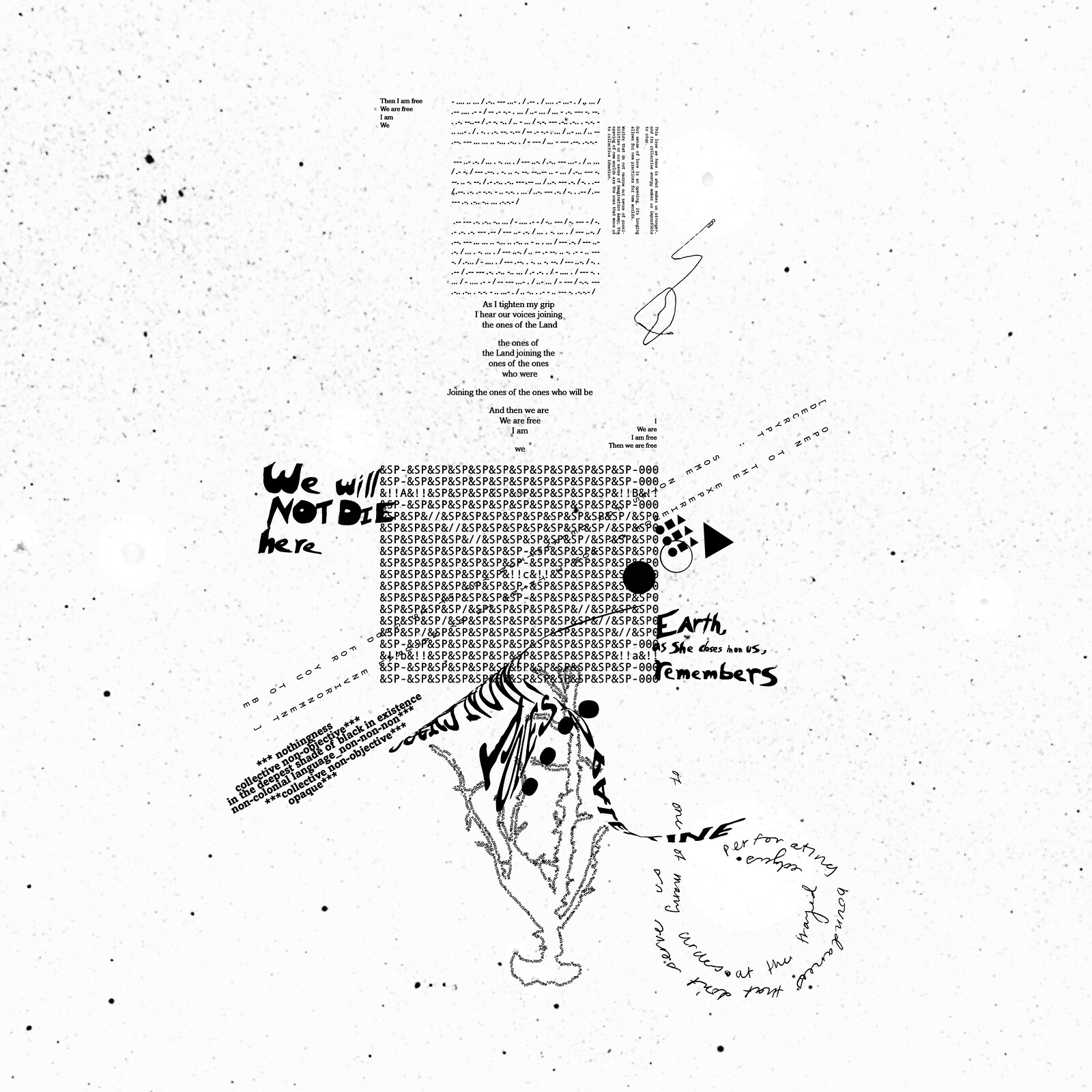

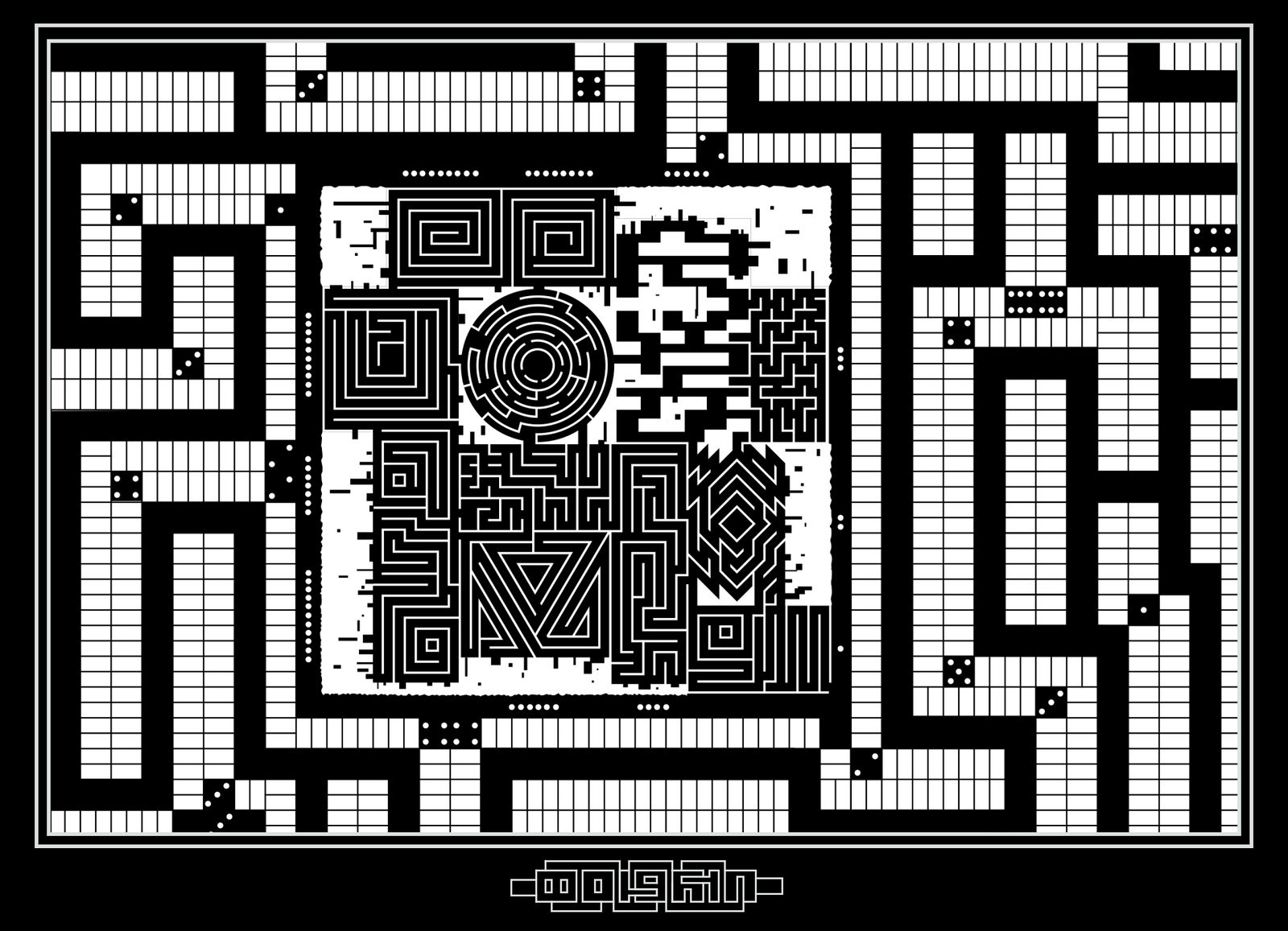

Dialectical Double Spiral of Modernity/Modernities, in WAI Think Tank, A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education (2023).

6. Fractals and Spirals

We often think of architecture through closed geometries. Squares, triangles, and circles make for very neat forms of enclosure and isolation, of control, of “architectons.” In this way, we are still too platonic. There are no perfect circles, squares, or triangles in nature. These are human abstractions we use to dominate reality. Fractals and spirals are all over nature; open forms that connect the infinitesimal with the immense. An architecture of unruliness must adopt spirals and fractals for a new geometry of openness, interconnectivity, and relationality. Only then will we understand that human creation is not separated from nature, but one instance of nature’s continuity.

Post-Colonial Postcard: Liberation Builder, from Worldmakers Unite! A Post-Colonial Play by Post-Novis, image WAI Think Tank/Post-Novis 2020.

7. An Architecture of Unruliness

Unruliness cannot be explained, since explaining is a way of ruling, but it can be modeled through examples and stories. Storytelling is the way unruliness reproduces. From the sugar plantations at the beginning of capitalism to the wired brain of today, power is a design, an architecture of control of both space and mind. It is fundamentally artificial. It operates under an illusion of separation. It cuts a given space or a given mind from the reality that surrounds it to control it: a virtual reality. An architecture of unruliness breathes in a radical connectivity, a principle of relationality in which nothing can be separated, nothing is by itself. Being is an illusion, a simulation; there is only relation, in all its materiality and openness. Misquoting Borges, we could say that for people who have experienced the end of the world many times, “philosophy is but a branch of fantastic literature.”27 Perhaps this is why the LRTS from its beginnings has been so interested in sci-fi, fantasy, afrofuturism, and speculative fiction, because these forms offer us a tradition that is an alternative to philosophy, an alternative to vertical explanation.28 This is also why we have learned from recent protests, insurgencies, and revolutions, that the form a rebellion takes deserves a lot of attention, and not just its ideological “contents.” Yet, paying attention to form cannot mean that we create formulas and reproduce them in another context like the “plantation” does.

We can hallucinate worlds as much as we want, but infinite forms are only accessible through the finite material relations that make up the here and now. The form of the tunnel or the crack in the wall that will permit our escape from the cage of solitary confinement is specific to each cage. It cannot be replicated. Each cage has its own escape route, and each route is irreproducible in its form. After we escape, we will have to create collective spaces, hotbeds, factories of worldmaking and worldlessness. There is no utopia there, no idealization, no romance. On the contrary, these collective spaces are difficult to build and require a lot of work. It is tiresome, because to get there requires a lot of imagination, and beyond that, organizing collectively.29 Only when we learn how to break away from individuality, a new collective intelligence can take over. What comes after that, though, is a lot of fun, and has no limits. It is the infinite without totality; the plurality of worlds and worldlessness; the vital play, like cats that, by playing, redefine their social relations and collective pleasures. Only pedagogy will get us there, but it is a pedagogy without a formula or textbook. It is an unruly pedagogy.30

A basic bibliography for the LOUDREADERS Trade School

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987.

Aponte Alsina, Marta. PR3 Aguirre. Puerto Rico: Sopa de Letras, 2018.

Benítez Rojo, Antonio. The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995.

Brathwaite, Kamau. Middle Passages. New York: New Directions, 1993.

Butler, Octavia E. Xenogenesis. New York: Guild America Books, 1987.

Cabral, Amilcar. Resistance and Decolonization. Translated by Dan Wood. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

Capetillo, Luisa and Julio Ramos, eds. Amor y anarquía: Los escritos de Luisa Capetillo. Puerto Rico: Huracán, 1992.

—. Love and Anarchy: The Writings of Luisa Capetillo. Translated by Roque/Raquel Salas Rivera. Puerto Rico: LOUDREADERS Press, forthcoming, 2024.

Césaire, Aimé. Discourse on Colonialism. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1972.

Combahee River Collective. The Combahee River Collective Statement: Black Feminist Organizing in the Seventies and Eighties. Albany, NY: Kitchen Table, 1977.

Darwīšh, Maḥmūd. The Butterfly’s Burden: Poems. Translated by Fady Joudah. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press, 2007.

Davis, Angela Y. Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and Torture. New York: Seven Stories Press, 2011.

—. Are Prisons Obsolete? New York: Seven Stories Press, 2003.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Translated by Brian Massumi. London: Continuum, 2008.

Dussel, Enrique D., and Aquilina Martinez. Philosophy of Liberation. Translated by Aquilina Martinez and Mary Christine Morkovsky. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2003.

Fanon, Frantz. The Wretched of the Earth. Cape Town: Kwela Books, 1961.

Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Woman, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, 2004

Ferreira da Silva, Denise. Unpayable Debt. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019.

Fischer, Sibylle. Modernity Disavowed: Haiti and the Cultures of Slavery in the Age of Revolution. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Freire, Paulo. Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Translated by Myra Bergman Ramos. New York: Continuum, 1993.

García, Cruz and Nathalie Frankowski. A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education. Puerto Rico: LOUDREADERS Publishers, 2020.

—. Universal Principles of Architecture: 100 Architectural Archetypes, Methods, Conditions, Relationships and Imaginaries (Minneapolis: Quarto Publishing, 2023

Glissant, Édouard. Poetics of Relation. Translated by Betsy Wing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997.

Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6, no. 1 (May 2015): 159–165.

Henni, Samia. Architecture of Counterrevolution: The French Army in Northern Algeria. Zürich: gta Verlag, 2017.

Illich, Ivan. Deschooling Society. London: Marion Boyars, 1971.

James, C.L.R. The Black Jacobins. 1938; New York: Vintage, 2023.

Kopenawa, Davi and Bruce Albert. The Falling Sky Words of a Yanomami Shaman. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed. New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

Lambert, Léopold. Weaponized Architecture: The Impossibility of Innocence. Barcelona: dpr-Barcelona, 2012.

Subcomandante Marcos and Juana Ponce De Leon. Our Word Is Our Weapon: Selected Writings. London: Serpent’s Tail, 2002.

Subcomandante Marcos and the EZLN. “The Sixth Declaration of the Lacandon Jungle.” Enlace Zapatista (2006). http://enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx/sdsl-en.

Mbembe, Achille. Critique of Black Reason. Translated by Laurent Dubois. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017.

—. Brutalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2024

Moten, Fred and Stefano Harney. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Ortiz, Fernando. Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar. Translated by Harriet de Onís. durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996.

Pappe, Ilan. The Biggest Prison on Earth. Simon and Schuster, 22 June 2017.

Philip, M. NourbeSe. Zong! Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2008.

Ramos, Julio. Paradojas de La Letra. Chile: Mimesis Ediciones, 2022.

Ramos, Julio and Martin Sostre. En Mi Celda: Escritos desde la cárcel. Puerto Rico: Editora Educación Emergente, 2024.

Rancière, Jacques. The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation. Translated by Kristin Ross. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1991.

Red Nation. The Red Deal: Indigenous Action to Save Our Earth. Brooklyn, NY: Common Notions, 2021.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia. Ch’ixinakax Utxiwa: On Practices and Discourses of Decolonisation. Translated by Molly Geidel. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity, 2020.

Rosa, Luis Othoniel. Caja de fractales. Argentina: Entropía, 2017.

—. Down with Gargamel! Translated by Noel Black. Berkeley: Argos Books, 2020.

Salas Rivera, Raquel. The Tertiary / Lo Terciario. Oakland, CA: Timeless, Infinite Light, 2018.

Sloterdijk, Peter. Critique of Cynical Reason. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

Snorton, C. Riley. Black on Both Sides. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Valencia, Sayak. Gore Capitalism. Translated by John Pluecker. Cambridge, MA: Semiotext(e), 2018.

Vergès, Françoise. A Decolonial Feminism. Translated by Ashley J. Bohrer. London: Pluto Press, 2021.

Wolf, Ilze. Unstitching Rex Trueform: The Story of an African Factory. South Africa: L’Erma Di Bretschneider, 2017.

Zambrana, Rocío. Colonial Debts: The Case of Puerto Rico. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021.

Post-Novis began with an exhibition in Omaha, in Maple St. Construct, on February 1, 2009. The exhibition consisted of artworks by Nathalatie Frankowski, Cruz García, Holly Craig and Hilary Wiese as well as the presentation of a collectively authored “Intergalactic” syllabus with Luis Othoniel Rosa. The Post-Novis Collective is also formed by undergraduate and graduate students part of FOLD, a curatorial and publishing seminar offered by WAI Think Tank at the College of Architecture at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Members of Post-Novis include: Marwa Al Ka’abi, Alec Burk, Aaron Culliton, Charles Dowd, Ben Friesen, Caleb Goehring, Trevor Kirschenmann, Tyler Koraleski, Jessica Larsen, Collin Meusch, Jordan Morris, Manuel Ruiz, Noah Schacher, Adrian Silva, and Megan Waldron. Find out more about Post-Novis here ➝.

Watch LOUDREADERS Session I (at loudreaders.com) June 19, 2020, in which Cruz García and Nathalie Franksowski discuss in detail the history of Loud Readers in tobacco factories, particularly the works of Luisa Capetillo and that of the scholars, Julio Ramos and Aracely Tinajero.

Very much in the interest of being a useful itinerant library, the LRTS is financing a project to translate and publish into English Julio Ramos’s iconic book in Puerto Rico, Amor y anarquía: Los escritos de Luisa Capetillo. Puerto Rico: Ediciones Huracán. Forthcoming by the LOUDREADERS Press, as Love and Anarchy: The Writings of Luisa Capetillo and translated into English by the renown Puerto Rican poet Roque/Raquel Salas Rivera, this book is expected to be published by the winter of 2024

This ten-day LOUDREADERS session took place at the School of Architecture at the University of Puerto Rico from June 23 to July 2 of 2023. Find the entire program and description of the event here ➝.

A brief study by Dr. Julio Ramos on the aesthetics of the LRTS is forthcoming in the next number of ARCH Newspaper which was based on Julio Ramos’s LOUDREADERS Session in Puerto Rico during the Summer of 2023.

Some of the books (highly collaborative) that have been published or funded by LRTS include: Cruz García and Nathalie Frankowski (editors). The Planetary Wretched: A Post-Colonial Narrative Architecture and Poetry Book. USA: LOUDREADERS Publishers, 2021. Cruz García and Nathalie Frankowski. A Manual of Anti-Racist Architecture Education. USA: LOUDREADERS Publishers, 2020 (online) 2023 (Printed). Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García. Universal Principles of Architecture: 100 Architectural Archetypes, Methods, Conditions, Relationships and Imaginaries. USA: Quarto Publishing, 2023. Julio Ramos (translation by Roque/Raquel Salas Rivera). Love and Anarchy: The Writings of Luisa Capetillo. Puerto Rico: LOUDREADERS Publishers, forthcoming 2024. Two books were also made possible through collaborations with the collectives of the LRTS: Luis Othoniel Rosa (art by Hilariy Wiese and translation by Noel Black). Down with Gargamel! USA: Argos Books, 2020; Luis Othoniel Rosa, (art by Guillermo Rodríguez, Nicole Delgado and Amanda Hernández. Translated by Katie Marya and Martina Barinova). Calima. Puerto Rico: La Impresora, 2023.

Critical references for LRTS for establishing the Caribbean as the center of the modern imperialist and capitalist project include: Antonio Benítez Rojo. The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective. USA: Duke University Press, 1995; Fernando Ortiz (trans. by Harriet de Onís). Cuban Counterpoint: Tobacco and Sugar. . USA: Duke University Press, 1996.

The most consistent reference given in the LRTS about how the control of the body of women was crucial at the beginning of capitalism and for its endurance is Silvia Federici. Caliban and the Witch: Woman, the Body, and Primitive Accumulation. USA: Autonomedia, 2004.

We are referring to the empires of Spain, Portugal, France, the English, the Dutch, and the USA, all of which (perhaps with the exception of Portugal) battled for control of the Caribbean islands, colonized and exploited them.

For the topic of the Plantationocene, in various LOUDREADERS sessions we have recommended Anna Arabindan Kesson. Black Bodies, White Gold: Art, Cotton, and Commerce in the Atlantic World. USA: Duke University Press, 2021. And also Fernando Ortiz mentioned above. Among the many discussions in LRTS of the plantation system perhaps LOUDREADERS Session 46 with Jason Ftizroy Jeffers and the book The Planetary Wretched (see above) might be a good starting point.

See Fernando Ortiz, Cuban Counterpoint as cited above.

See Julio Ramos and Álvaro Contretas (eds.). Farmacopea literaria latinoamericana Antología y estudio crítico (1875-1926). 2nda edición. Puerto Rico: La Criba; Chile: Cuarto Propio, 2023.

For a direct reference and critique of the words and actions of the “Puerto Utopia” crypto-billionaires that is often referenced in the LRTS see Naomi Klein. The Battle For Paradise Puerto Rico Takes on the Disaster Capitalists. USA: Haymarket Books, 2020. For an in-depth discussion on how Puerto Rico is today an experimental laboratory for debt and neoliberal extraction watch LOUDREADERS Session 23 with the philosopher Rocío Zambrana, and LOUDREADERS Session 19 and LOUDREADERS Session 24 with the poet Raquel Salas Rivera.

Tw okey references often quoted in the LRTS for how Shakespeare’s The Tempest has been “cannibalized” by Caribbean culture see Roberto Fernández Retamar. Todo Calibán. Puerto Rico: Ediciones Callejón, 2023, and Raquel Salas Rivera. Antes que isla es volcán / Before Island is Volcano. Boston: Beacon Press, 2022.

A discussion about how contemporary urban planning and architecture in Caribbean nations today continue the legacy of 500 years of colonialism was at the center of the ten-day LOUDREADERS session in Puerto Rico in the summer of 2023, specially in the interventions of Isabelle Jolicoeur (Haiti) and the project of Island City Lab (Jamaica). The LRTS recently edited this essay-chronicle, precisely about gentrification in Puerto Rico and the new versions of settler colonialist in the island: Juan Carlos Quiñones. “At the End of the Tunnel: Bad Bunny’s Vid(e)ocumentary Sheds Light (and Music) into Boricuas’ Struggle against Dispossession” in Journal of Architecture Education. Special Issue, Reparations. Volume 77, Issue 1, 2023.

See Sianne Ngai. Ugly Feelings. USA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

For Luisa Capetillo’s concept of the “plurality of habitable worlds” see the iconic Puerto Rican edition of Julio Ramos (ed.). Amor y anarquía: Los escritos de Lusia Capetillo. Puerto Rico: Ediciones Huracán, 1992, which translation by Roque/Raquel Salas Rivera is forthcoming in the LOUDREADERS Publishers (2024). For the most famous reference (a recurrent one in LRTS) of how the Zapatistas of the EZLN speak about the plurality of worlds see their famous “Sixth Declaration of the Selva Lacandona” EnlaceZapatista.ezln.org.mx, 2005.

From the “Sixth Declaration” cited above.

For a standard reference to the Occupy Wall St. movement see Sara Van Gelder (ed.). This Changes Everything: Occupy Wall Street and the 99% Movement. USA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2011.

See Roland Végsö. Worldlessness After Heidegger: Phenomenology, Psychoanalysis, Deconstruction. Edinburgh University Press, 2020.

For the publication of the original poem see the January 2nd, 2013 entry enlacezapatista.ezln.org.mx. For the poem and a study of this protest in a historical and critical context see Alvaro Reyes. “Zapatismo: other geographies circa ‘the end of the world’”. in Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 33(3), 408-424.

Reference to Julio Ramos in this series.

See LOUDREADERS Session 45 with Dr. Ilan Pappé about ethnic cleansing in Palestine and the recent genocide in Gaza.

See the forthcoming issue (15) on “Networks of Solidarity”, edited by Cruz García and Nathalaie Frankowski of Revista Informa of the College of Architecture at UPR. Particularly, Nora Akawis piece documenting the “Conference of Butterflies” in which many Palestinian intellectuals and other international figures in solidarity with Palestine held a joint 12 hour seminar style conversation.

We are refering to Kafka’s famous story, “Report to the Academy”.

See LOUDREADERS Session 23.

See Jorge Luis Borges famous story, “Tlön, Uqbr, Orbis Tertuis”. For a discussion about Borges and the Zapatistas see LOUDREADERS Session 25 with Luis Othoniel Rosa.

See LOUDREADERS Session 2 about Ursula LeGuin’s The Dispossesed.

See also LOUDREADERS Session 35 with Luis Othoniel Rosa on “Identity and Control.”

See Luis Othoniel Rosa. “Luisa Capetillo or the pedagogy of unruliness” in Small Ave. No. 69, November 2022.

Loudreading is a collaboration between e-flux Architecture, WAI Architecture Think Tank, and Loudreaders Trade School supported by the Mellon Foundation, re:arc institute, the Graham Foundation, Producer Hub, Iowa State University, GSA Johannesburg, Universidad de Puerto Rico–Rio Piedras, and the inaugural ACSA Fellowship to Advance Equity in Architecture.