This soundscape is intended to be listened to while reading the following text. Anna Engelhardt and Mark Cinkevich, Infrastructural Horror, 2024.

In the nineteenth century, a ruin was a landscape for gothic horror. Today, monsters pervade infrastructure. With sprawling limbs and hulking frames, towering oil platforms, writhing wires, and bottomless mines are omens of contemporary dread. Infrastructural horror is a way to investigate and expose the infrastructure of colonial expansionism in its inherent monstrosity. As a genre, it aims to create discomfort, repulsion, or suspense by exposing the architecture of dispossession and destruction as an omen.

Early morning. The incessant, eerily soft hum of the engines barely resonates against the steel walls. The refinery is luminous in the window. I’m awake—not because a sudden noise ruptured my sleep, but because of a new and unusual quiet. Something’s not right. I strain to listen. I am frightened, but of what? Of the muted vehicles, distant voices, barking dogs? Up until now, I’ve been frightened of nothing. I listen. I listen, but to what? The smell of oil and metal hangs heavy in the air. I open my cupboards and go to the window.

I look down. My entire building is dark. How long will this blackout last? In the distance, the refinery towers over the landscape. The rain has just stopped, but water is still dripping from the steel framework. Bright lights cast long shadows across the metal walls and wet machinery. The structure looks familiar. Still, it doesn’t quite match its surroundings. It is not out of place, but rather, out of proportion. It has grown so much that it has become uncanny, unrecognizable.

It’s just a refinery, I say to myself. It shines like it always has. Everything is the same as yesterday. Except now, in the blackout, the red light stares right back at me. Its glow, hypnotic and dim, pierces through the deep gloom that has fallen over this edge of the city. I look away. Red reflections haunt me in the myriad of wet tankers, cargo trains, and railway tracks. Not a single person is around, neither on the streets nor looking out of the windows. If anyone else was to look at the refinery, they probably wouldn’t notice anything special, perhaps only ask: why isn’t the factory smoking? Is there a strike?

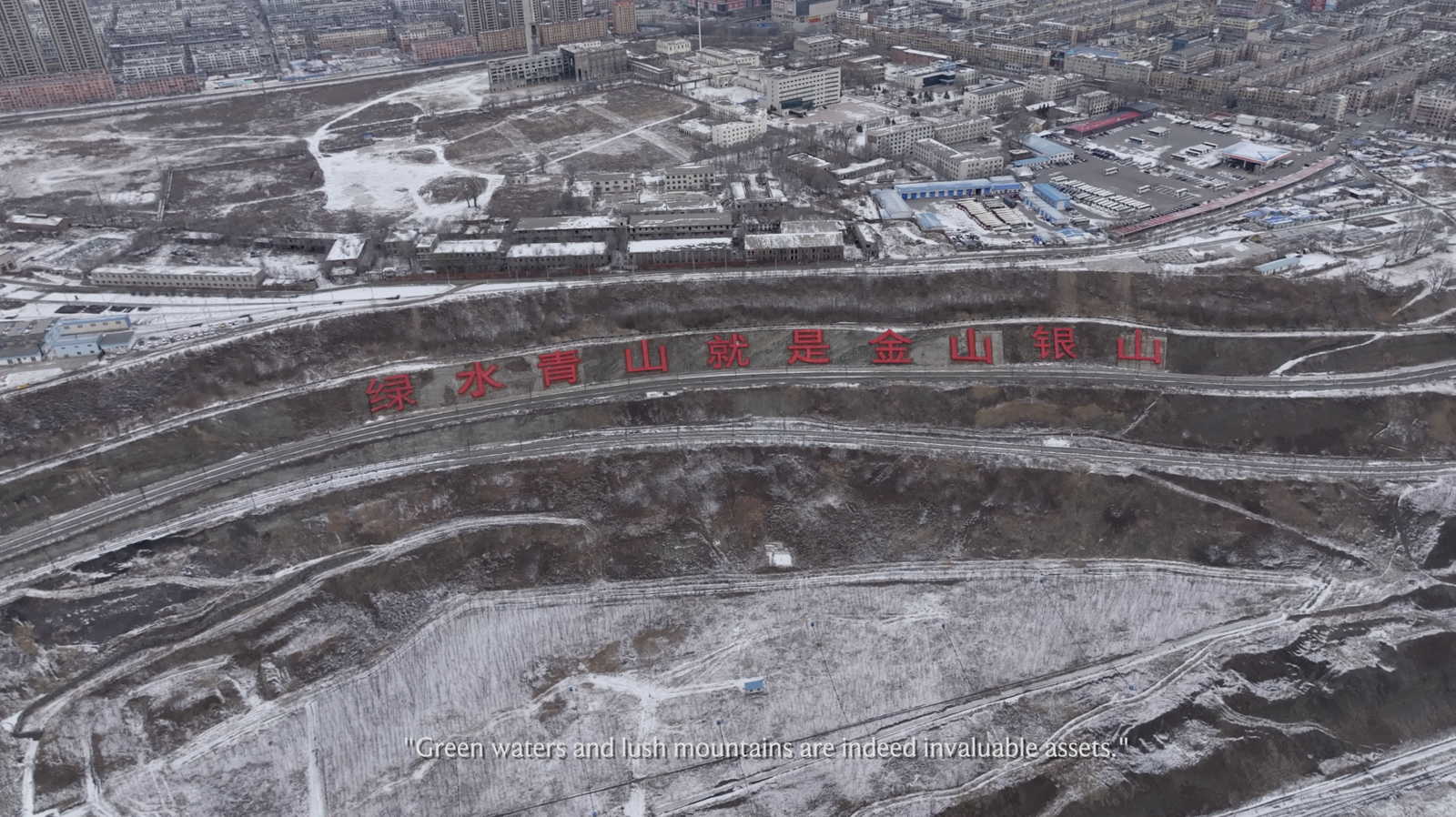

Author unknown, Magnitogorsk Iron and Steel Works, 1930s. Source: National Historic Museum of South Ural.

In the horror genre, attempts to hide the violence of infrastructure prove futile. Tension and violence cannot be contained and eventually leak through into the settler household. We watch how liquids directly inherit the symbolism of colonial extraction as toxic residue burns through the skin, or as a glistering black slime of oil or tar causes agonizing pain and turns the scene into a polluted wasteland. Blood coming out of the sink in a haunted house. Protests against “the smell of Ukrainian blood in Russian Gas” come from the same impulse.1 They signify a moment when infrastructure fails to maintain the facade of settler normality.2

Unlike horror genres, which rely heavily on shock value, infrastructural horror operates through suspense. It focuses on revealing the foreboding in the architecture of dispossession and destruction, creating discomfort and repulsion. The suspense in infrastructural horror can take generations, slowly poisoning those in proximity to these structures, and span distances whose true dimensions can’t be entirely grasped. The genre hinges on the enormity of infrastructure and the violence it allows for—the sublime.

The distant lights of the refinery slowly crawl towards me from the horizon. I carefully drive towards them along the highway, across another old, skewed industrial bridge. I’ve heard so many superstitions. Many people who worked at the refinery often complain about their vision. The problem was that people went blind. Not completely blind, but something akin to night blindness. It’s said that they didn’t go blind from the darkness or any kind of flashes—although there were reports of flashes—but from a deafening noise, a noise that was so intense it caused blindness. Doctors said it couldn’t be. They asked the workers to think again. But the workers insisted: it was a tremendous noise that blinded them. And yet, no one else heard it.

For a while, I drive in complete silence, even from my own thoughts. With no streetlights, the urge to look back onto the road is overwhelming. I know no one is there. But when the headlights only illuminate what’s up ahead, I feel a heavy gaze. I can’t help it. Of course there’s no one. I don’t look back, but the darkness thickens behind me. A sudden shiver runs through me; not a cold shiver, but a shiver of agony. I speed up, uneasy with being alone in this blackout, stupidly frightened without reason at my profound solitude. I think I might have heard something. The asphalt is gradually getting more and more cracked from the weight of loaded trucks. Must be the car.

Fredric Jameson has observed how imperialism operates by obfuscating structural connections between daily life in the metropole and suffering and exploitation in the colony.3 Such disjunction is infrastructural. Infrastructures of extraction convert violence into comfort, keeping these two realities disjointed on opposite sides of the pipeline. Their function does not end with creating and maintaining a material connection of extraction. Extracted resources undergo stages of material transformation that gradually cleanse them of their violent origin. This refinement allows them to enter domestic spaces under the guise of comfort, convenience, and warmth. In the words of Paul Guernsey, “emergencies are an element of perception,” and settler infrastructures specifically aim to obfuscate “environmental emergencies as cycles of settler colonial violence and ecocide.”4 Colonial infrastructure aims to contain, conceal, wash, and filter out the horrors of extraction for those who use it.

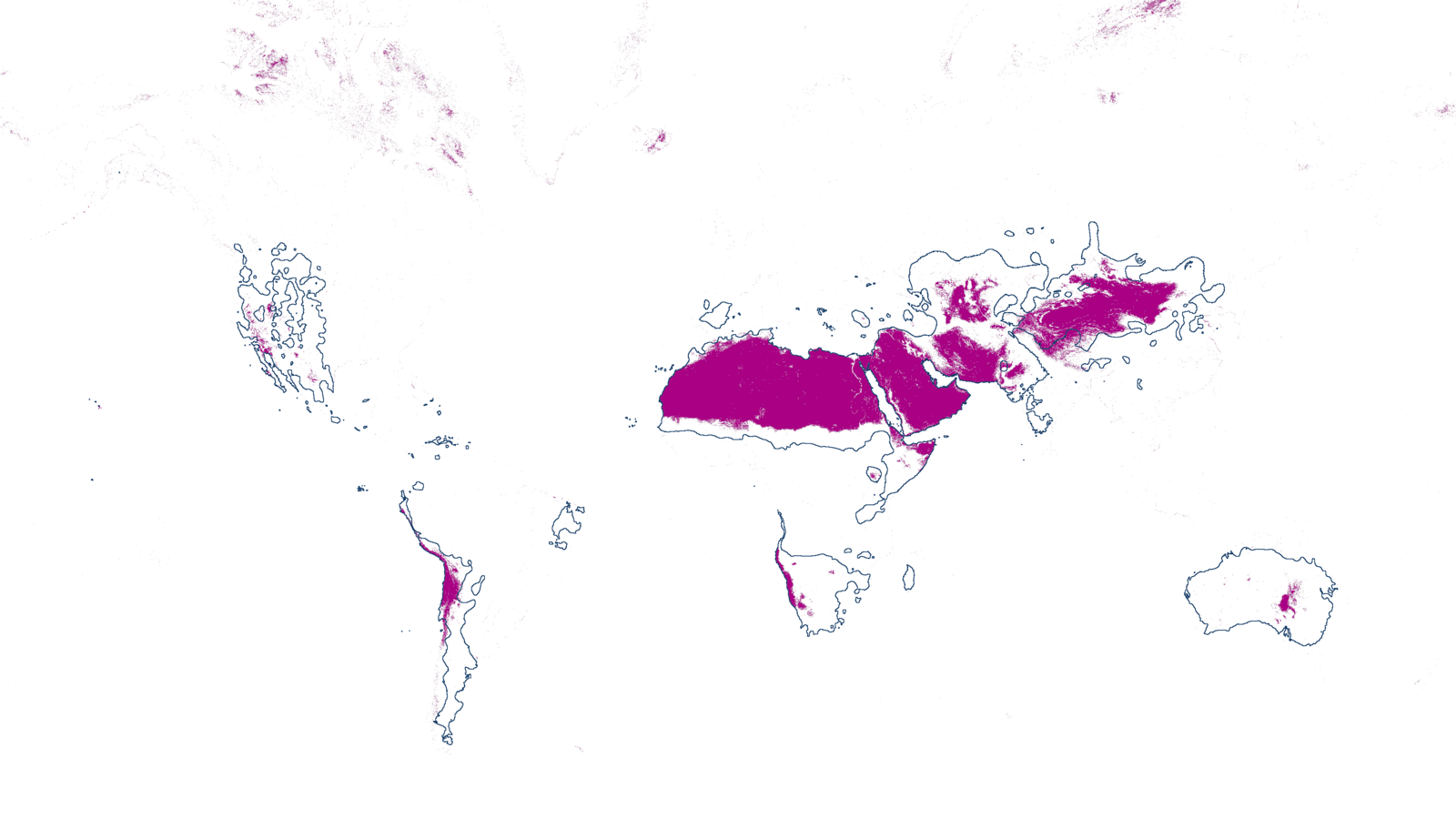

The oil refinery is a key node in such a system of obfuscation. Although sanctions against Russian oil were introduced by the EU, UK, and US following the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian molecules of energy have continued to enter the European market, as well as others markets that have claimed to forbid them. When Russian oil gets processed at the Italian refinery, it “switches nationality.”5 Russian oil becomes Italian oil, allowing it to be consumed as a domestic product and even be sold further abroad. In May 2023, the ISAB refinery in Sicily, formerly owned by Russian energy corporation Lukoil, was sold to an unknown private equity firm GOI Energy Limited.6 GOI Energy was founded in Cyprus in 2022, right after the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, and has made no other deals apart from the ISAB Refinery. The CEO of GOI Energy is Michael Bobrov, a Russian businessman with dual Russian-Israeli citizenship. All the current managers of the refinery are former Russian Lukoil managers who kept their positions under Bobrov. The ISAB refinery is Europe’s third-largest oil refinery and is a critical part of Italy’s refinery system, accounting for 30% of Italy’s diesel supply and 20% of its total energy capacity. Processing Russian oil at a refinery in Italy not only directly funds the war in Ukraine, but also sustains the operation of extractivist infrastructures on indigenous peoples’ land in Russia. Infrastructural horror does not invent but amplifies what is already felt and seen by those in proximity. It might only seem to be a metaphor for those who have never felt its consequences.

The turn into the small gas station looms ahead. Everything around is wet and quiet. The rustle of tires rolling on gravel soothes me. I stop the car and kill the engine. It is impossible to pinpoint the exact moment it started. The hissing has been growing slowly along the blurry boundary between the audible and the ultrasonic. I do not make any noise. I hear nothing. No, I do. The noise is quite loud, a whistling whisper, indistinct and inhuman. It comes from below the road. I feel wires and pipes running along the road edges. I listen to the pulsating hum deep beneath the concrete.

A nasty feeling that perhaps there really is no noise creeps into my mind. Maybe I am just losing it. It is so familiar that I earnestly try to convince myself that the whisper has just been my imagination. It’s all due to stress. I try to relax and think of nothing, hoping that along with my anxiously racing thoughts, I can expel that infernal noise from my mind. I manage to halt my thoughts, but in my momentarily empty mind, the sound becomes more resonant, louder and clearer. It grows stronger as I notice a crack across the asphalt.

My whole body shivers beneath my jacket. The crack widens into a jagged hole, luring me to look inside. The metallic whistle reaches an unbearable peak as I glance below. One of the storage tanks, framed by jagged and splayed metal edges, emerges from the dark. The noise beckons me to climb down into the abyss, but I hesitate. The asphalt feels like thin ice, and my feet are numb, ready to stumble. I come closer. There is nothing. Is it the emptiness that is hissing?

The noise comes from the depths. It is going to seize my head, close my eyes. The sound is now utterly unbearable. It’s impossible to focus on even the simplest of thoughts. It drowns me like a pool of stagnant water. I can hear everything so well that I don’t need to look anymore.

I am no longer feeling well.

S. Jayanti, “The Vital Missing Link in the U.S. Sanctions Against Russia,” Times of Malta, February 26, 2022, ➝.

Mark Rifkin, “Ordinary Life and the Ethics of Occupation,” in Settler Common Sense: Queerness and Everyday Colonialism in the American Renaissance (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

Fredric Jameson, “Modernism and Imperialism,” in The Modernist Papers (London: Verso, 2007), 157.

P. J. Guernsey, “The Infrastructures of White Settler Perception: A Political Phenomenology of Colonialism, Genocide, Ecocide, and Emergency,” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 5, no. 2 (2022): 588-604.

Gabrielle Hecht, “Interscalar Vehicles for an African Anthropocene: On Waste, Temporality, and Violence,” Cultural Anthropology 33, no. 1 (2018): 109-141.

“Italy Conditionally Approves Lukoil Refinery Sale, Sources Say,” Reuters, April 11, 2023, ➝.

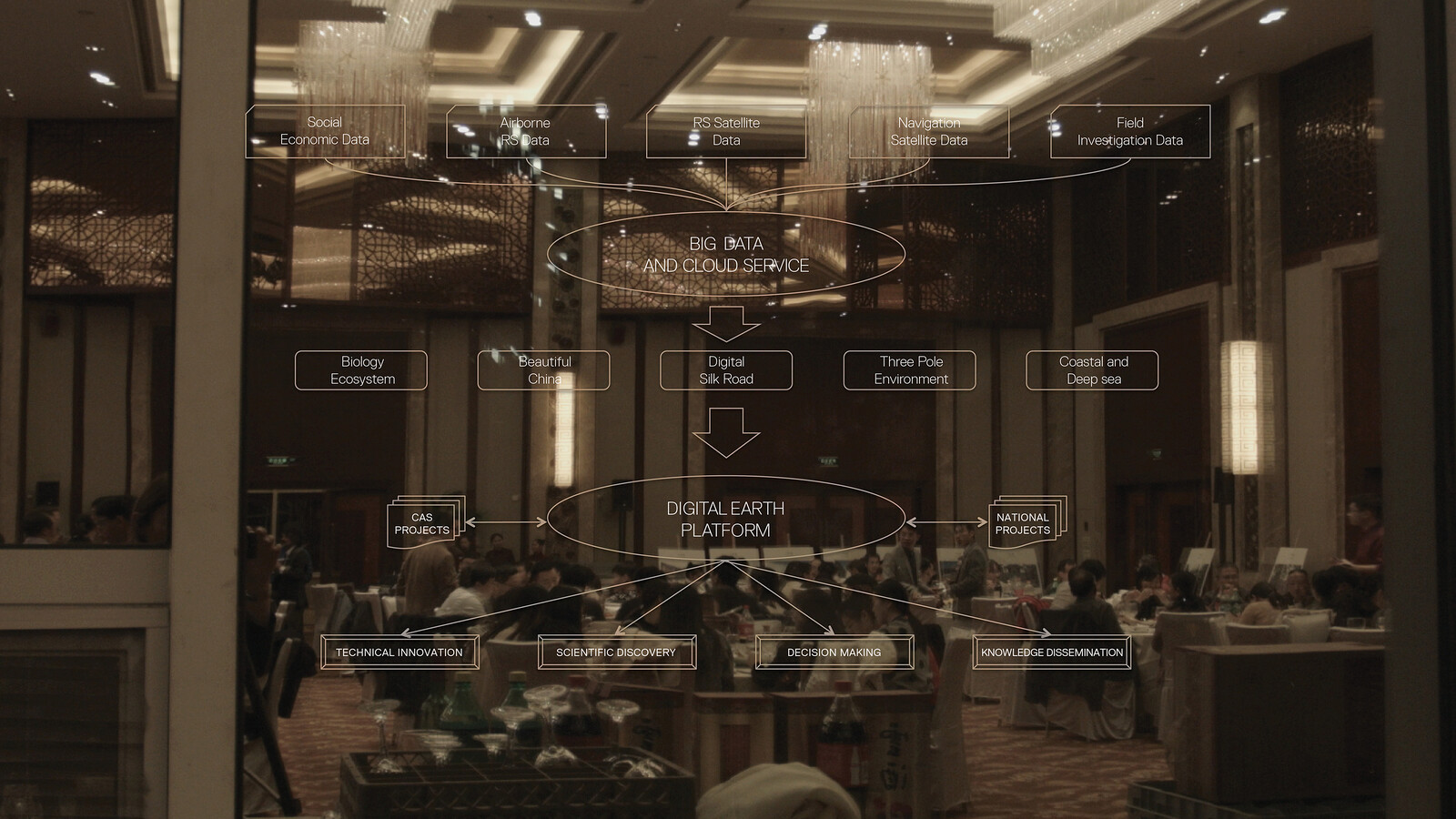

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).

Category

Subject

This text is based on Anna Engelhardt and Mark Cinkevich’s research for their forthcoming project at Medialab-Matadero Madrid and excerpts from their film “Onset,” co-written with Alex Quicho. The audiotrack is an excerpt from the “Onset” score, which consists of a soundtrack by Yikii, underscore by Regular Citizen, and design by Alisa Kibin.