USSR pavilion, Venice Biennale, 1968. Photo: Oleg Velikoretsky.

We know that the West itself was produced by certain historical processes operating in a particular place in unique (and perhaps unrepeatable) historical circumstances. Clearly, we must also think of the idea of “the West” as having been produced in a similar way.

—Stuart Hall, “The West and the Rest,” 19921

It is commonly and rightfully asserted that the institutional format of a national pavilion is an antique remnant of the previous historical function of the Venice Biennale—namely, the demonstration of the belonging of advanced nation-states to the “universal” (and, thus, international) historical world of modernity. Although the Giardini intended to appear extraordinarily diverse this year, at least one exhibition in one national pavilion fitted properly within the colonial-era architecture: the Bolivian show housed in the Russian pavilion. After the pavilion was banned in 2022 due to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the cultural bureaucrats serving Russian colonialism were inventive enough to reenact the Soviet tactic of exploiting the struggles of the Global South for their geopolitical interests.

What happened, in fact, was that Russia lent the pavilion to Bolivia for an exhibition titled “looking to the futurepast, we are treading forward,” curated by Esperanza Guevera, the minister of Cultures, Decolonization, and Depatriarchization in Bolivia. This decision was announced just a few weeks before the opening of the biennial and was meant to celebrate the two-hundredth anniversary of the Plurinational State of Bolivia. “Drawing from Aymara cosmovision, this exhibition views the contemporary experience as anchoring us in the present moment, which holds within it the seeds of the future, emerging from the fertile soil of our past,” reads the curatorial note. The exhibition indeed engages with pre- and counter-modern visual codes and practices that are under threat of erasure by Western imperialism, thus giving them new life within the practice of contemporary artists.

However, neither the curatorial frame nor the individual artworks question the deeply sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, and internally racist neoliberal cultural policies of the Russian Federation. A telling case is Elvira Espejo Ayca’s installation presenting spinning wheels and a loom, described in the booklet as symbolizing maternity and the circularity of time. The series of “gay propaganda” laws adopted by the Russian Federation in recent years brings a specific tonality to such a thematic focus. What I want to account for here are the geographies of Russian colonialism that inform the exhibition’s institutional frame—that is, the manipulation of geographic polarizations by Russian colonialism.

The Conundrum: “Decolonial” Geographies of Russian Colonialism

The Bolivian exhibition, or rather its public presentation, sets off alarm bells about the essentialization of geographic denotations like the “West,” the “Global South,” and the “former Soviet space.” By “essentialization,” I mean the process that occurs when these markers are uprooted from situated struggles and become terms of global artsy slang. The cultural diplomatic strategy of the Russian Federation has been to instrumentalize precisely this perplexity regarding the relations between these three geographic entities.

The necessity of accounting for such instrumentalization is foregrounded not only by the decade-long brutal extermination of Ukrainians, Crimean Tatars, Roma people, North Azov Greeks, and other peoples populating the territory of Ukraine. It is equally, if not even more, conditioned by the glaring absence of any considerations of the colonization of Indigenous peoples living on the territory of the Russian Federation in any of the “anti-” or “decolonial” policies initiated by this state. The decision to lend the pavilion has a special significance, given that during the twentieth century alone, the contemporary territory of Russia served as the ground for the resettlement of Chechens and Ingush, Crimean Tatars, Caucasian Greeks, Oirat-Kalmyks, Karachays, Kurds from Transcaucasia, and peasantry from all over the USSR, to name a few.

These processes were neglected and, moreover, silenced in the Russian pavilion via the extractivist geographic imaginary of Russian colonialism. Accounting for colonialism here allows us to address the complex cultural, historical, social, and political processes conditioning the individual exhibition at this year’s biennial. In my usage, “Russian” in “Russian colonialism” is in no way a national attribution but a denotation of the historical continuity of colonial relations from the Russian Empire to the former Soviet space, throughout the transformations of their means and ideological masks. I will limit myself here to revisiting a few episodes from the Russian-Soviet pavilion’s history that are relevant to the current situation, and then reflect on the conundrum of Russia’s colonial “decolonial” geographies, with particular regard to their extractivist engagement.

The West and the Rest: The Cold War Articulation

The Russian Empire was among the first seven states to establish its pavilion in the Giardini during the opening decades of the Venice Biennale. By 1924, the pavilion building, designed by imperial architect Alexey Shchusev, housed the first Soviet exhibition. This group show, which featured works by Kazimir Malevich, Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin, Aleksandra Ekster, and ninety-four others, promised to elevate the international reputation of the Soviet socialist project. In the years that followed, this possibility was interpreted by Stalinist functionaries as the potential for the international supremacy of Soviet culture.

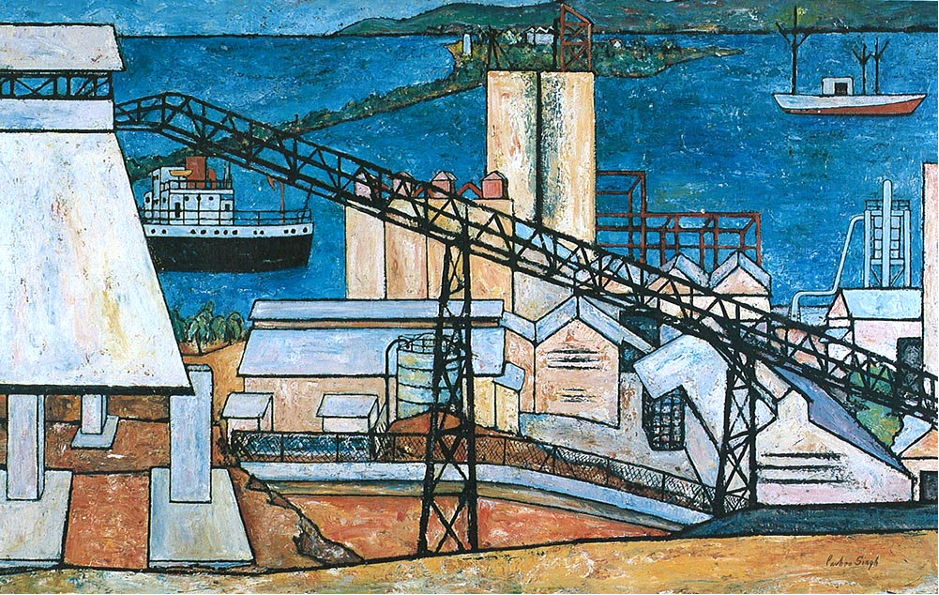

The subsequent Giardini shows, before the pavilion was closed after 1934, were characterized by an unreserved commitment to socialist realism. A prominent figure during this period’s exhibitions was the painter Aleksandr Deineka, whose career in Venice continued even after the closing of the pavilion, due to Mussolini’s personal admiration of his works.2 The general climate of this period at the biennial can be described as a competition between the normative aesthetics of hegemonic systems and their respective models of human culture (e.g., between Stalinism and fascism). It is not surprising that eventually the same visual codes were accepted by opposing parties. But what is indeed stunning is the reemergence of Deineka’s name among the participants in the first postwar exhibition in the Soviet pavilion.

The exhibition took place in 1956, the same year Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev announced his de-Stalinization policies in a speech titled “On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences.” Alongside the partial rehabilitation of political prisoners, this speech condemned Stalinist resettlements. Undoubtedly, this did not result in any corresponding changes to the federational structure of the USSR; nor did it lead to reparations or restitution for those oppressed Indigenous peoples who survived deportations and their consequences. The multiple colonial exterminations under Stalinist rule were considered mere effects of the “cult of personality” and, therefore, were deemed to be resolved by the proclamation of its end. Additionally, in 1956, Khrushchev announced “peacemaking” policies, specifically the support of colonized peoples struggling for independence worldwide.3 Despite the decisive role of these policies at that historical moment, it should be acknowledged that they simultaneously marked the complete and tragically rapid “delegation” of colonialist biases exclusively to the West.

In this way, the geographic frames of colonialism and racism were superficially reduced to the space beyond the Iron Curtain via state ideological control. In his speech at the 1960 UN General Assembly, Khrushchev acknowledged that “the former outlying regions of the Russian Empire had practically the same status as the colonies.” But he then claimed that “the peoples of Central Asia and Transcaucasia and other nationalities inhabiting the Russian Empire received complete freedom after the October Revolution.”4 As proof, Khrushchev recounted the growth in electricity production and the increase in the number of technical specialists in the region. Such a vision equates the “complete freedom” of breaking with colonialism to modernization, technological progress, and, in Khrushchev’s own words, “overcoming backwardness.” In her research on the formation of territorial and economic regulations within the postrevolutionary USSR, Francine Hirsch shows how these attempts at modernization kept pace with the rehabilitation of colonialism in the early debates. This reached such a scale that on outrageous “non-imperialistic model of colonization” was developed.5 Thereafter, Cold War polarization allowed Khrushchev to omit these nuances: the colonial remnants of the Russian Empire were declared to have completely vanished with the articulation of the difference between “the West” and “the Rest.”

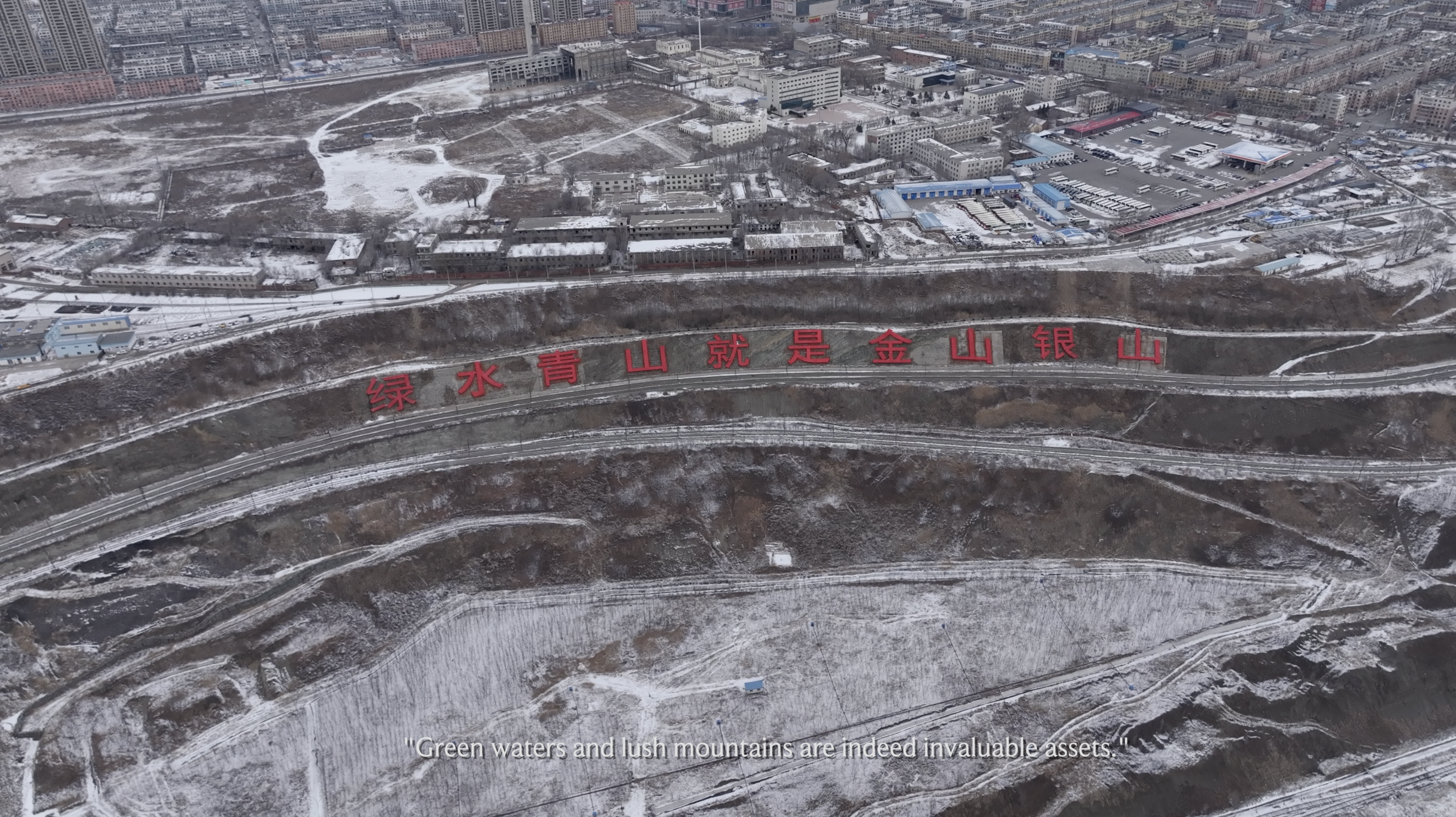

Consequently, in the following three decades, this self-concealment of Russian colonialism paved the way for the conquest of gas- and oil-rich West Siberia.6 Despite the proclaimed antagonism, the pipelines stretched in a western direction, primarily to Germany. Against the backdrop of memory erasure, the titanic efforts by NGOs and associations of Indigenous communities in this region to calculate the damage and losses suffered can hardly express the scale of colonial violence. Here I can recount the story of my friend and her mother, both of whom belong to the Nenets people: When my friend's mother was a child, she was taken from her family in the tundra and sent to a special boarding school,7 where her personal belongings were taken away, her hair was cut, and she was forced to speak exclusively in Russian. This is how she had to learn just how deeply humanist and inclusive the society of developed socialism was. Surveying the vast literature available in the closing years of the Soviet era, James Forsyth, the author of A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia’s North Asian Colony (1992), tells the story of these policies of language homogenization and enforced settlement in the light of Moscow’s economic interests and the industrial development of the region.8

Vitalism of Modernization

The artistic advances of this society were festively exposed at the 1956 exhibition in Venice. The pavilion as an institution facilitated the artistic expression of modernization as a link in a larger historical process of social change. Yet this historical development was measured by monolithic—overly Western—criteria, which allowed the subjugation of subaltern communities in the USSR. The pathos of Khrushchev’s proclamations about “overcoming backwardness” in the former Russian empire’s territories, and his reductionist geographic definition of colonialism, echo the imaginary historical timeline exposed at the 1956 Soviet exhibition in Venice.

Delving into the “processual logic of the Soviet system,” Fredric Jameson notes that the processuality of the system’s formation in the historical transition from capitalism created “pockets which we may often call ‘utopian.’”9 He suggests that we see Deineka’s output within the Soviet system as harboring such a utopian investment. Jameson contrasts the mighty bodies of workers depicted in Deineka’s paintings with Nazi imagery of idealized bodies. Deineka’s figures express an excessive “productivity of a body,” which rapidly increases as modernization unfolds. Thus the painter is said to perfect “a kind of vitalism of modernization.”10 In the Giardini in 1956, such vitalism significantly contradicted the general range of artistic approaches. The Soviet press expressed deep reservations about the omnipresence of abstractionism at Venice, which the reporters termed “bezobrazie,” a word meaning both “absence of image” and “outrage” in Russian.11

The notable innovation of the 1956 biennial was that the old competition between different models of culture became far more rigorously bipolar during the Cold War. The contours of these poles fit the West-Rest divide within the institutional logic of the Soviet pavilion. Meanwhile, the Iron Curtain was meant to muffle the clashes of colonial violence within the territories under Soviet rule.

Neoliberal in Content, Soviet in Form

The brief history I’ve sketched reveals the continuity of the institutional functions of the pavilion in producing geographic differences, just as it makes these differences more acute. At face value, “looking to the futurepast, we are treading forward” marks a radical break from the Soviet era’s tendency to propagate the values of modernization and progress. Indeed, it calls for the recognition of cultural practices, modes of living, and modes of worlding that have had to struggle with and survive the invasion of modernity. However, what’s preserved is a geographic polarity reminiscent of the Cold War, including its silencing of power imbalances within “the Rest.” How can we understand this double movement?

Russian colonialism’s reapplication of the Cold War–era West-Rest divide cannot obscure the major change it has had to face: the transition from Soviet socialism to post-Soviet—and global—capitalism. The celebration of modernization and “bright prospects of humanity” were replaced by neoliberal development and the decorative preservation of what has not yet been destroyed by this development. Along with most of the military infrastructure of the USSR and Siberian fossil fuel extraction facilities, the Russian Federation inherited the Soviet pavilion in the Giardini. Since then, this pavilion has not shown any vision of the future, or past, or futurepast, except that of the superstructural forms required for the conciliation of the unequal property regime.

The current functioning of this institution can be described by rephrasing the famous Stalinist slogan about cultural policy: instead of “socialist in content, national in form,” it is neoliberal in content and Soviet in form, but also militarist and still colonial. Indeed, in 2023, the Plurinational State of Bolivia and the Russian Federation signed an agreement concerning the development of lithium extraction in Bolivia, which envisaged a total investment of $600 million from Russia.12 The pavilion’s institutional strategy this year equally illustrates the current condition of Russian colonialism and, more broadly, of the biennial as a conglomerate of institutions that conscientiously carries the continuity of its colonial heritage. Although historical timelines of the twentieth century have changed, the extractivist geographic imaginary appears to transform not so rapidly.

Stuart Hall, “The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power,” in Formations of Modernity, ed. Stuart Hall and Bram Gieben (Polity Press, 1992), 186.

Andrei Kovaliov, “In Defense of Deineka: A Strong Mittelspiel,” in Deineka: Graphics (in Russian), ed. Evgenii Korneiev (2011), 66.

Joy Gleason Carew, Blacks, Reds, and Russians: Sojourners in Search of the Soviet Promise (Rutgers University Press, 2008), 204–5.

Nikita Khrushchev, The National Liberation Movement: Selected Passages (1956–1963) (Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1963), 80.

Francine Hirsch, “Towards the Empire of Nations: Border-Making and the Formation of Soviet National Identities,” Russian Review, no. 59 (April 2000): 207. See also Hirsch, Empire of Nations: Ethnographic Knowledge and the Making of the Soviet Union (Cornell University Press, 2005). I express my appreciation to Tahmina Inoyatova, Sasha Shestakova, and Svitlana Matvienko for sharing these texts in the frame of the reading group they organize, “Decolonial, Post-Colonial, and Post-Soviet.”

This dimension of Russian colonialism was profoundly explored by Oleksiy Radynsky in his research-film Where Russia Ends (2024, prod. Lyuba Knorozok, ed. Taras Spivak).

On Russian colonial educational institutions, see Elena Liarskaya, “‘They are just not like other people …’: Some Stereotypical Views about Tundra Inhabitants Held by Educators in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug” (in Russian), Antropologicheskii Forum, no. 5 (2005).

James Forsyth, A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia’s North Asian Colony (1581–1990) (Cambridge University Press, 1992), 399–400, 406–7.

Frederic Jameson, “Aleksandr Deineka, or the Processual Logic of the Soviet System,” in Aleksandr Deineka (1899–1969): An Avant-Garde for Proletariat (Fundación Juan March, 2011), 86. Exhibition catalog.

Jameson, “Aleksandr Deineka,” 91. In this regard, Christina Kiaer’s suggestion that we see Deineka’s oeuvre as “experimental form that purposively challenges the conventions of its medium as a response to the shocks of modernity” deepens rather than contradicts Jameson’s point of view. See Kiaer, Collective Body: Aleksandr Deineka and the Limit of Socialist Realism (University of Chicago Press, 2024).

See, for instance, Nikolai Abalkin, “On the Venice Exhibition” (in Russian), Inostrannaya Literatura, no 2 (1957). The term “bezobrazie” was used not only in art journalism but also in art history and aesthetics. It was in the title of Mikhail Lifshitz’s book Кризис Безобразия (1968), which English translator David Riff translated as The Crisis of Ugliness: From Cubism to Pop-Art (Brill, 2018).

See →.