I. Politics of a New Eurasia

You are the soul of all those who died believing in the happiness that would come in the future. And now see, it has come. The future in which people do not live for something else but for themselves.1

—Victor Pelevin, The Sacred Book of the Werewolf

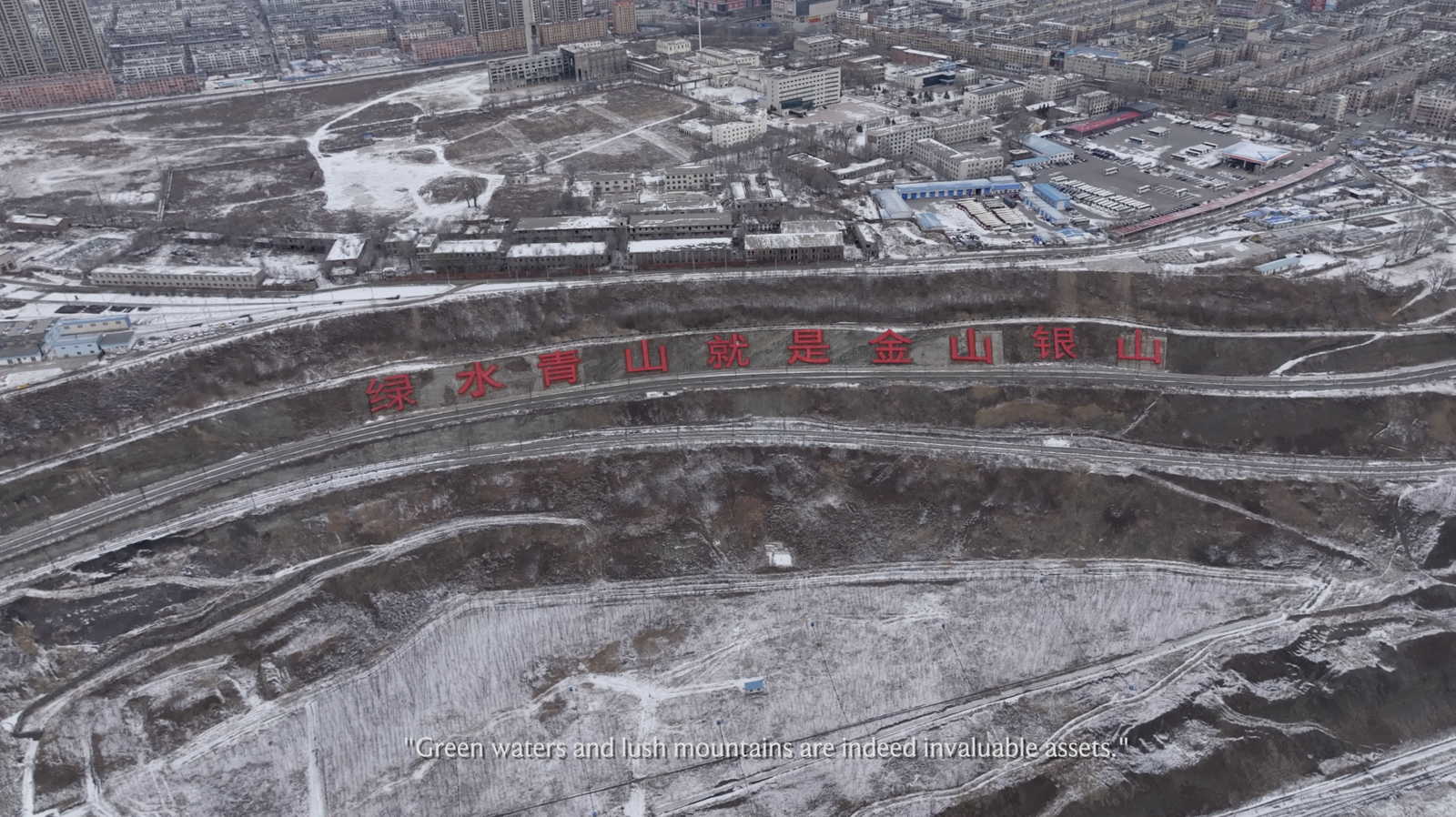

Over the past few years, the flimsy states and territories that cover the Eurasian continent as lightly as gauze have been getting pushed and pulled into a new way of being. In response to temperatures creeping ever higher, forests burning, and deserts growing, China is reordering the internal logic of the supercontinent under the banner of a technological dream of endlessly renewable electricity.2

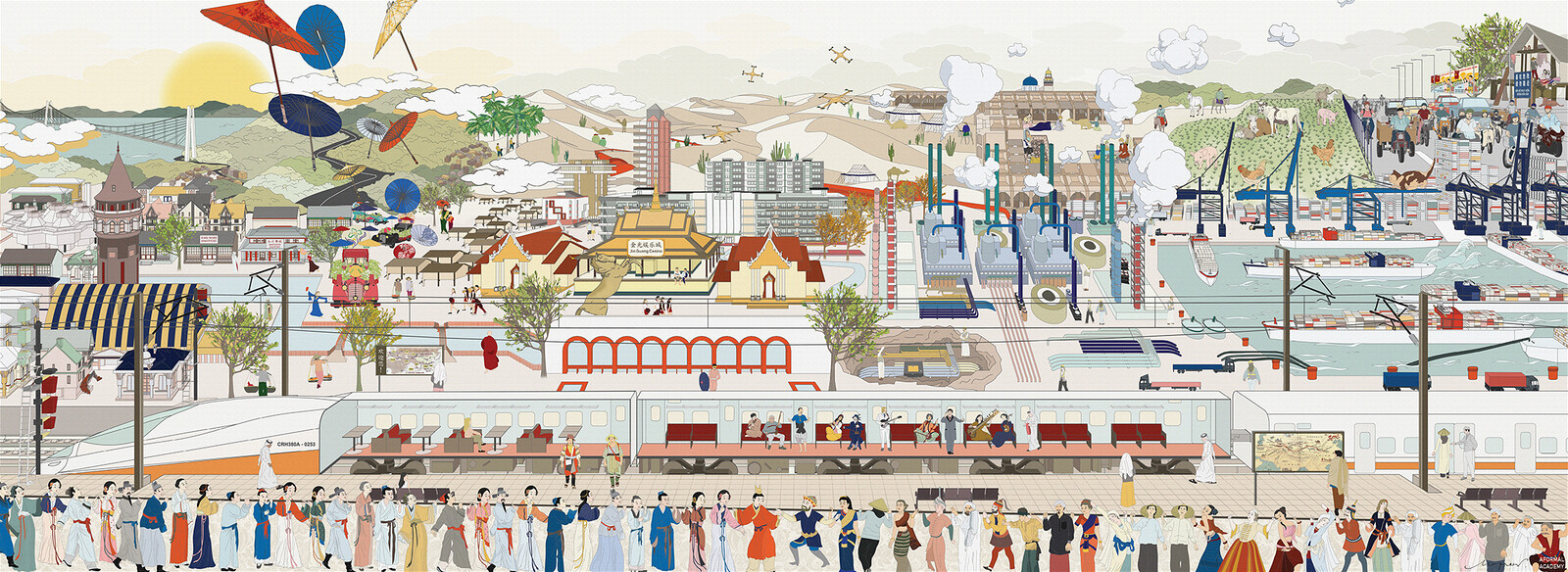

The sources of this electricity, as if in fulfillment of an ancient pagan dream, are the rays of the sun, the breeze across the prairie, and the cascades of mountain rivers. While new reservoirs of fossil fuels and seams of ore are being exploited here too,3 two-thirds of all wind and solar projects that are currently under construction are located in China,4 and the country is expected to install more than half of the world’s total solar power in 2024 alone, both within and outside its borders.5 Across huge distances and extreme temperatures—what the English geographer Halford Mackinder called the “World-Island”—new towns are being built, even new capitals, all linked by lengths of glass and plastic wires to vast fields of solar panels and wind turbines and mega-dams.6

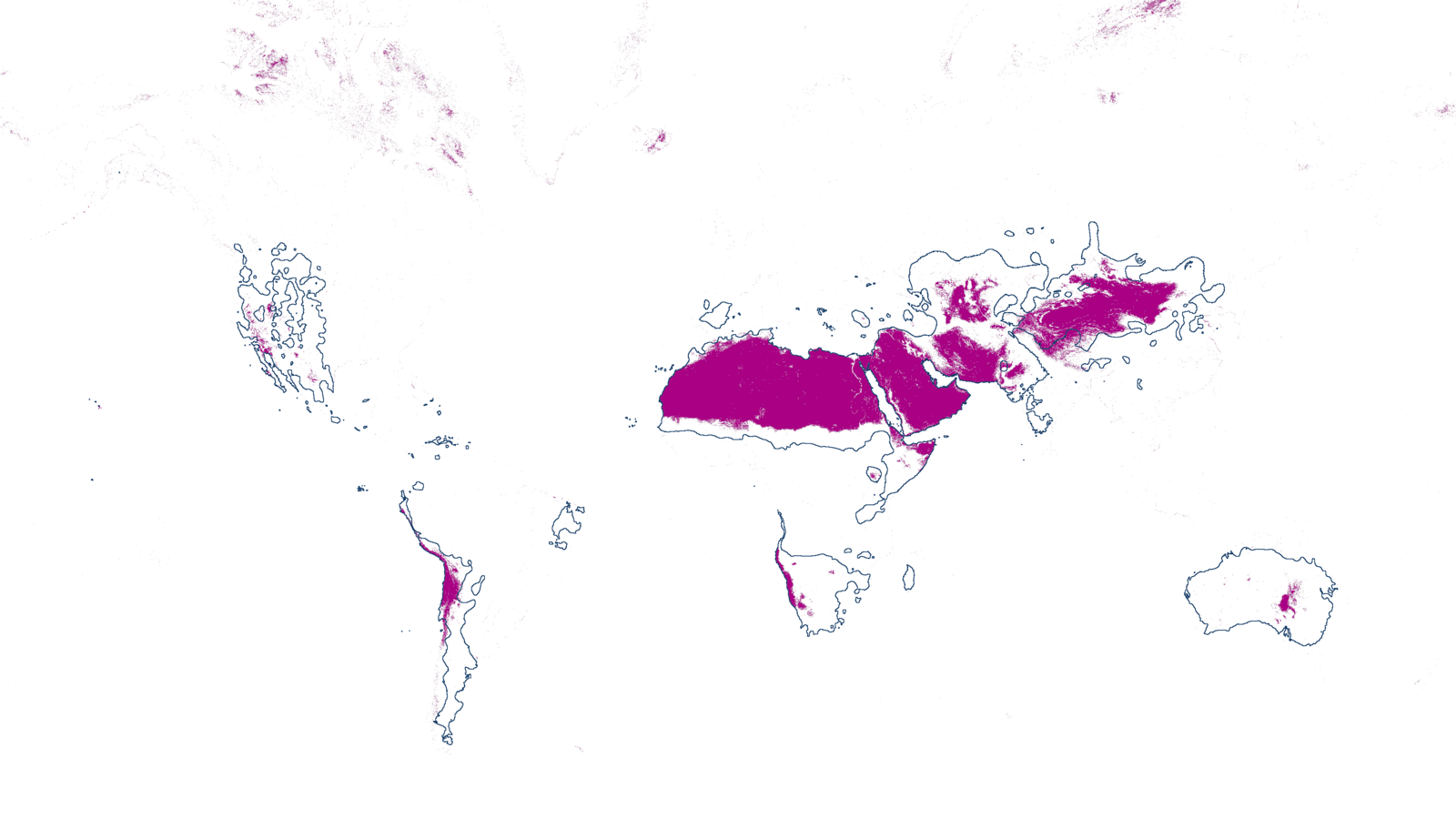

This monumental industrial transformation is reshaping the internal logic and economic priorities of countries from Mongolia to Pakistan, Kazakhstan, and Saudi Arabia. It’s reordering political alliances and trade routes across the entire post-Soviet space and the Arab world—or, in historical terms, most of the Mongol Empire’s territory circa 1259. In seeking to decarbonize, China is upending Eurasia’s and indeed the global economy, whose denomination is the petrodollar, and restructuring the United States-led world, partially fulfilling Zbigniew Brzezinski’s prophecy: “[A] coalition allying Russia with both China and Iran can develop only if the United States is shortsighted enough to antagonize China and Iran simultaneously.”7

While the Chinese are building a new Eurasia in the form of a totalizing machine, Russian intellectuals have had a different fantasy of Eurasia for at least the past hundred years. From Alexander Dugin and Sergei Karaganov to Lev Gumilev before them, this fantasy derives from some romantic vision of communist, pagan, primitive, anti-modern Mongol hordes. Gumilev, the strange and bitter celebrity ethnologist of Russia’s 1990s, prophesized a return to a Mongol way of life, one infused with the purity of the endless earth and the mysticism of shamans, in which the life of the people shines, and shines, and shines. Before him, Fyodor Dostoyevsky decried the Crystal Palace in London, built of iron and glass for the 1851 Great Exhibition, as a symbol of Western modernity, one that was alien to the Russian soul.

Russia today revels in playing the innocent victim, just trying to defend itself, gathering the clans to fight Western modernity. Not only is that an incoherent position, it is ironic, because by fleeing from a complicated, decadent, urban, enlightened Europe, Russia is delivering itself into the jaws of a more sophisticated machine than twenty-first-century Europe could ever hope to be. China is a hyper-organized, rationalist, urban technocracy that forcibly integrates foreign peoples and embraces a generic globalism as much as anywhere on Earth. So if the Russian Eurasianists think that by discarding Europe and allying with China they can turn their back on the contemporary, they are sadly mistaken.

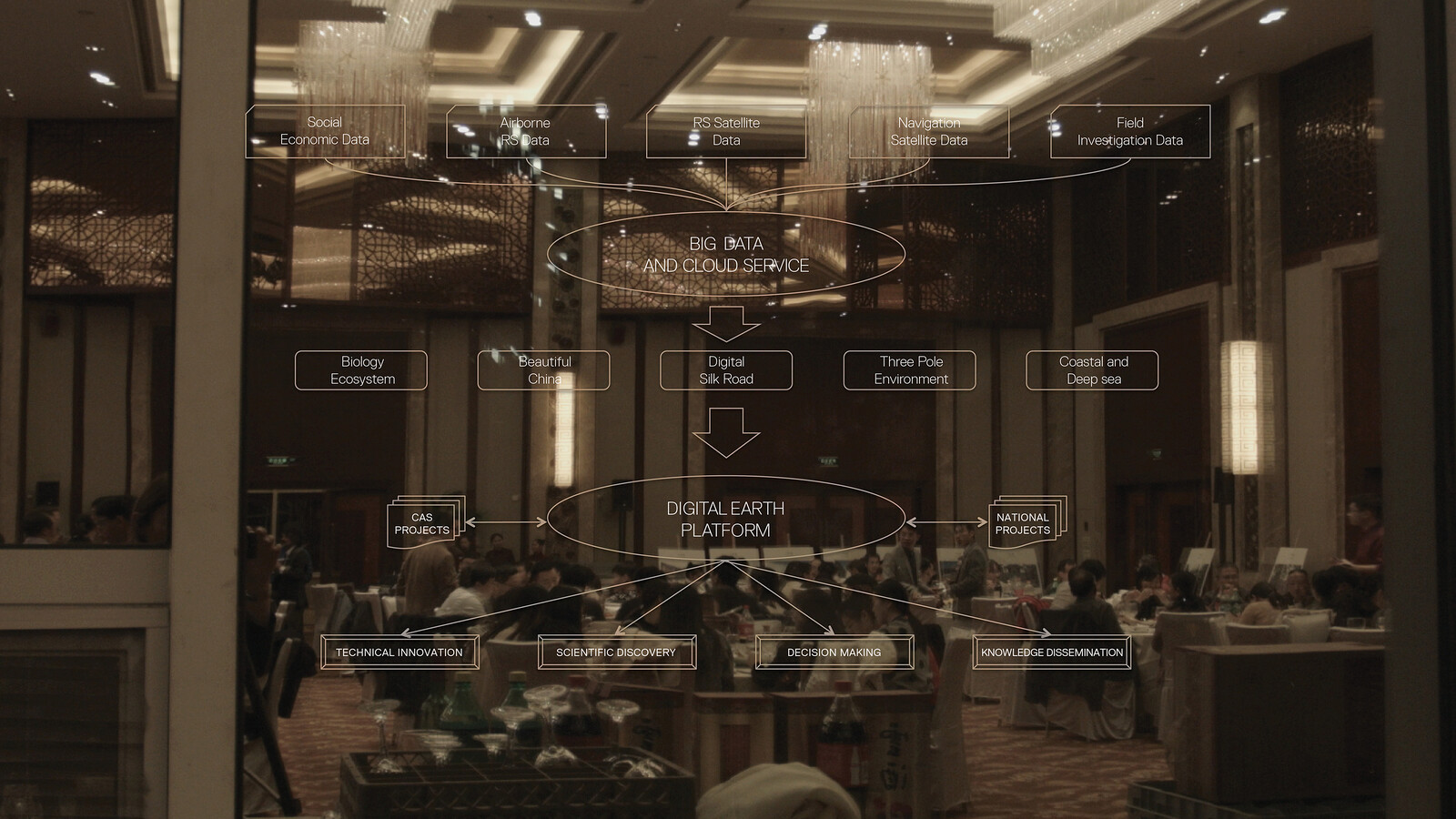

At the heart of the contemporary Chinese empire is a digital megastructure that might be the true protagonist of our time, reordering energy, land, and human life around its need to adjust to a new enviro-political reality. When COP29 opens in November in Baku, a Eurasian city built on oil that is today crisscrossed by infrastructure with Chinese characteristics,8 a latter-day Pax Mongolica will see itself in the mirror: a Sinified Eurasian continent remaking itself with solar power.9

For those who think in English, this can all feel like the realization of a baleful prophecy about the emergence of a totalitarian empire. But if the Eurasian steppe is the backdrop to human history, it’s a history of human insignificance in the face of natural forces and distances. A preoccupation with emperors misses the deeper truth of people lost in an endless emptiness, searching for meaning and for a way to transform their circumstances.

II. The Third Neighbor

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations. … It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation. It has resolved personal worth into exchange value. … [M]an is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.10

—Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto

Late last year, hoping to understand what the new Eurasian world looks like to Mongolians, I dropped by the International Conference of the Mongolists in Ulaanbaatar. Mongolia’s two neighbors, Russia and China, both have large populations of ethnic Mongolians. As the great game heats up between China and the West over resources for the renewable energy transition, the Mongolian elite is betting on their “third neighbor”—the West—to help them triangulate a shifting balance of power.

Ulaanbaatar’s immediate surroundings are soothing, with rolling hills and blue skies that might remind you of the famous Windows XP wallpaper. But seen from the air on a flight from Beijing, the city appears like an oasis surrounded on every side by the endless and expanding orange of the Gobi Desert. The sandstorms here are so brutal that they impact Beijing, hundreds of miles away; planting trees as a natural barrier against the desert has become one of the principal areas of cooperation between China and Mongolia. Making things worse, Mongolia is drier now than it has been for 260 years, further jeopardizing the way of life of nomadic herders.

Stuck in traffic, I noticed that seemingly everybody was driving a Prius, many with license plates from suburban Osaka or Kanazawa dealerships. Apparently, there’s a brisk resale market of Japanese used cars, which are loaded onto ships at Vladivostok to be distributed throughout inner Asia.

Mongolia isn’t rich—with a per capita GDP of $5,000, it is a long way from China, South Korea, and Russia. But optimistic Mongolians forecast that figure to grow to $20,000 by 2030. (The math is friendly since the population is so small.) Copper, lithium, graphite, and some of the other metals found in the Gobi are critical for the batteries, wind turbines, and solar panels that will fuel the energy transition; the Oyu Tolgoi mine, far to the south, near the border with China, is one of the largest copper mines in the world. As the US and China compete to secure these resources, Mongolia has gained a new allure; entrepreneurial locals, conscious of having squandered opportunities in the thirty years since the socialist period ended, plan to make the most of it.

For countries with minerals relevant to the energy transition, from Chile to Indonesia to Mongolia, the great transition that is just beginning offers an opportunity to become key players in an upturned world. While China has flirted with bans on the export of certain rare earth metals, Mongolia could export what China refuses to. There’s only one catch: anything going in or out of Mongolia must pass through, or over, Russia or China.

Mongolia has a highly ambiguous relationship with Russia. The architecture of Mongolian modernity was almost entirely imposed by Joseph Stalin. Until the Soviet period, Mongolians were mostly nomads, who had to be forcibly and violently dragged into modernity via collective farms and industrial projects, which were run poorly. There’s a lot of resentment toward Russia’s past and present role as an autocratic meddler in Mongolian affairs. This lingers even within the Russian Federation and its community of Siberian Buryats, a Mongolian ethic group from land that straddles the present-day border between Russia and Mongolia: why should they put their lives on the line to conquer Kyiv for Moscow, a city in which they would still be treated as second class citizens? Many would prefer to live in Ulaanbaatar, and openly wonder whether Russia, a multiethnic empire ruled by Muscovites, can survive at all.

Russia’s wane in Mongolia might mean China’s wax. China is, of course, a familiar interlocutor for Mongolians; some privately boast that they founded Beijing (during the Yuan Dynasty, when it was called Khanbaliq). But it’s in the interest of the Mongolian state to keep a firm distinction between the Chinese province of Inner Mongolia and Mongolia the independent country, lest they fall quietly into Beijing’s warm embrace. This has already happened once, and it didn’t end well: Chinese Inner Mongolia’s GDP per capita is nearly three times that of Mongolia, but the Mongolian language is marginal there, and ethnic Hans constitute 80% of the population. The Mongolians of Ulaanbaatar view the Inner Mongolians as sleepers in a poisoned dream whose true selves may never again wake up.

III. From Shanghai to Riyadh

We must go out to meet the world. Not only do we want our products to “go global,” we also want our industrialization to go global, and our high-quality talent to go global. We can spread industrialization to every corner of the world. Many of our scientists and technicians will travel around the world to work, bringing with them civilization, a dignified existence, and relief from poverty. This is one thing that Westerners have been unwilling or powerless to accomplish.11

—Wang Xiaodong, “A Study of the ‘Industrial Party’ and the ‘Sentimental Party’”

While the huge industrial transformation China is driving likely benefits Mongolians, it alarms Saudis, who feel that their ability to sell China oil now has a question mark over it. In spite, or perhaps because, of this, the new direct flight between Shanghai and Riyadh is cheap, as little as $300 each way. Somebody is clearly subsidizing a new flow of people between China and the Arab world. Chinese companies are building new factories in Egypt, and Arab leaders are gravitating toward Beijing.12 Whatever you think about US policy in the Middle East, many Arabs dislike it, and this has given China an opportunity.

A lot is changing in Saudi Arabia that might come as a surprise. There are new economic ties with China and a renewable energy boom.13 In a country that not long ago had religious police telling women how to dress, a luxury hotel on an island off the western coast put on a swimsuit pageant in May.14 There are big plans for diversifying the economy and building a utopian mega-city in the desert.15 At the root of many of these changes is the sense that the country’s fossil-fueled foundation is no longer tenable, at least partly because China is decarbonizing. In response, Saudi Arabia is reinventing itself, a real and visible shift behind which is a material compulsion to find some new reason for being.

When I visited Riyadh for the Diriyah Biennial, I wondered what it meant to look at the future optimistically, and why people in some places have that perspective, while people in other places don’t. Gumilev called it “passionarity,” a kind of momentum he thought caused a group to unite and find power and strength.16 I remember when the United States had it. Is it lost for good, or will it come back? And what does the breathtakingly rapid Saudi transformation reveal about how frustratingly stuck societies can suddenly find a new groove?

Driving the changes in Saudi, a Shanghai-based friend who advises the Saudis on their Chinese investments told me, is the certainty that the world has reached peak oil. China, the world’s biggest oil importer, is taking measures to get energy in different ways. So must Saudi Arabia change, as the world changes around it.

Despite the basis for the Saudi economy likely disappearing within the next ten years, bitter wars in the region and the sweltering weather (it’s 100 degrees Fahrenheit by April), optimism and plans for a different future pervades much of Saudi Arabia. In this situation, the irrational concept of passionarity began to make sense. The Saudis are getting their act together while Americans, for all of our advantages, are screwing around. It doesn’t seem like something that can be explained by logic. Saudi Arabia is “progressive,” an acquaintance who works on the Saudi government’s investments in China told me—not in the sense of a set of causes, like in the United States, but in the literal sense of progressing toward a future that will be different, perhaps even better than today.

“Saudi Arabia is the new China,” I’d heard from people who’d spent time in both countries. It sounded a bit ominous, considering the wave of social transformation in China starting around 2008. Back then, it felt like anything could happen, with everybody able to project their own fantasies onto the future. But ever since, China has been a society in flux; much hasn’t worked out, and there is a kind of hangover from reality not meeting expectations: abandoned housing complexes, companies in debt, individuals for whom the dream never came true, college grads who never found work, etc. Saudi might feel the same in fifteen years, when skeletons of grand ambitions stand empty and forlorn.

And yet, in many concrete ways, Chinese cities are much more livable than they used to be. People who know what they want and have a plan to get it sometimes succeed. If you dream it, you can at least try to do it.

IV. The Green Prison

Prior to Gumilev, we typically looked at ourselves through the eyes of the West, seeing in our country … only oppressive centuries of barbarism, bloody conflicts, and senseless, stagnant, lifeless existence.17

—Aleksandr Dugin

In the Stalinist 1940s, Lev Gumilev was marooned in what he called the “green prison” of Siberia, so desperate to leave that he volunteered for the Soviet military.18 For an anthropologist and self-styled aristocrat, preferring to participate in the Red Army’s assault on Berlin over life in Siberia was analogous to King Kong choosing Manhattan over the jungle. Like Dostoyevsky before him, Gumilev felt stranded in an endless and uncaring Asia.

Similarly to the Nazis, Gumilev built a worldview around ethnicity. But rather than seeing ethnicity as something biological, his view was based on an almost mystical relationship between a group and the landscape around it. He saw humanity as intrinsically defined by ecosystems, like a species of animal or plant. Different ecosystems engender different types of life; for Gumilev, the Eurasian type was the product of Siberia’s green prison. Homo sovieticus was truly different, on an ethnic level, from the seafarers of Western civilization. But that ethnicity was understood as malleable, the product of moments of mutation and change in reaction to climate or ecological circumstances. In the end, the Soviet-Eurasians were just a group thrown together by contingency and an unwillingness—or inability—to be admitted to the world of capitalism.

In the Norillag gulag—which today is Nornickel, a huge mining conglomerate that recently announced plans to open a facility in China—Gumilev collected folklore of the Tungus and other local tribes, in between suffering diseases and eating herring.19 In his journal, he wrote:

In the rain and frost I built this city,

And so that it would be higher than the hills around it

I turned my own soul in a stone,

And used the stone to decorate the road.

It was here that his idea of “ethnogenesis” took form: that a group of people would be fused into a People with a capital P by a shared environment and the ways that they lived within its conditions.20 Norillag broke Gumilev. He reconstituted himself in a search for meaning, trying to conjoin his resentment of being excluded from European civilization with the experience of living in Siberia and its vague, mythic notions of the Eurasian steppes.

The most articulate and sophisticated interlocutor of the “Eurasian idea,” Gumilev’s insights came not from archives but from his own life in Siberian resource-extraction slave camps. During the tumult of Russia’s 1980s and 1990s, his ideas became widely popular. Today, Russian pundits write about how “Russia must permanently abandon Europe and turn to Asia.”21 These men advocate the “Siberization” of Russia. But Siberia is a peripheral resource colony of the metropolis. Perhaps this is fitting, seeing as how China is set to make of Russia what Siberia has been to Moscow: wild, brutal, empty of people but full of valuable resources, a place that outsiders can project their ideas of spirituality onto.

Gumilev’s image of Asia was a kind of Mongol purity invented as a psychic coping mechanism. The actual Asia that the Russian state is encountering today is China, and China is extremely different from Mongolia. In fact, this might be contemporary Russia’s great tragedy. Making choices that in the short term seem inevitable, Moscow is refiguring what Russia is in the world in the long term. Western media emphasizes its new separation from Europe and America, but in Russian cities and industries, the new dominance of China will be felt more strongly.

V. Harbin: Anti-Capital

You can start out in Russia with whatever you like—conservatism, socialism, liberalism—but you will always end up with roughly the same thing, that is with the thing that actually exists.22

—Vladislav Surkov

Harbin, a perverse metropolis situated where northeastern China bumps into Russia, is a city whose mood is one of tragic, lost beauty; a shipwreck of its own contradictions. Walking the streets, it is impossible to recognize it as a capital of a new world order. At most, it is the seawall against which Atlantic modernity crashes and retreats.

Much as the Soviet state rearranged the natural and the psychic world of humans like Gumilev, the digital world that China is constructing is pushing reality around: the foods people eat, their activities, the ways they meet romantic partners.

When Putin visited Harbin in May 2024, Chinese and Russian state railroad companies signed agreements to expand cross-border trains.23 Chinese bloggers, fantasizing about Russia’s potential, speculated about bringing Vladivostok—which Sergei Karaganov proposed as a new capital for Russia—within reach, digitally and by road or rail.24 Russia, after all, has the natural resources for an empire, but not the population. China has people, but not enough resources. It’s a perfect match.

Life desires its own propagation, and the Chinese techno-industrial structure’s expansion seems to follow the logic of expansion for its own sake, or to defend itself against the rival Atlantic structure. The wind that blows through Siberia, the rays of sun beating down on Karakorum, and the settlements across the Eurasian steppe will intertwine with each other, at least for a time. Ultimately, this will serve the goal of feeding more resources into the Chinese economic machine; power will reshape this most desolate of landscapes, wrapping more and more lives in its embrace.

Victor Pelevin, The Sacred Book of the Werewolf (Священная книга оборотня) (2004; Viking Adult, 2008).

Saule Akhmetkaliyeva, “A Promising Green Energy Resource in Kazakhstan: Solar Power,” Eurasian Research Institute, n.d., ➝.

Harry Dempsey and Max Seddon, “Norilsk Nickel to move copper smelter from Russia to China as sanctions bite,” Financial Times, April 22, 2024, ➝.

Amy Hawkins, “China building two-thirds of world’s wind and solar projects,” The Guardian, July 11, 2024, ➝.

Euan Graham and Nicolas Fulghum, “Solar power continues to surge in 2024,” Ember (blog), September 19, 2024, ➝.

Stephen Chen, “Could China build a second capital in the far-western deserts of Xinjiang?,” South China Morning Post, April 30, 2023, ➝.

Zbigniew Brzeziński, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives (Basic Books, 1998).

Xinhua, “Xi says China, Azerbaijan upgrade bilateral relations to strategic partnership,” State Council, People’s Republic of China, July 4, 2024, ➝.

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848), ➝.

Wang Xiaodong, “A Study of the ‘Industrial Party’ and the ‘Sentimental Party’,” Green Leaf, January 1, 2011, trans. Dylan Levi King for the Center for Strategic Translation, ➝.

Jesus Mesa, “Saudi Arabia’s Historic First Swimsuit Show in Photos,” Newsweek, May 20, 2024, ➝.

“Overview,” Vision 2030: Saudi Arabia, ➝.

Quoted in Mark Bassin, “Neo-Eurasianism and the Russian Question,” in The Gumilev Mystique: Biopolitics, Eurasianism, and the Construction of Community in Modern Russia (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016).

Bassin, The Gumilev Mystique.

Vita Spivak, “Western Sanctions Are Pushing Russian Metals Producers Into China’s Arms,” Carnegie Politika (blog), July 12, 2024, ➝.

Bassin, The Gumilev Mystique, 129.

Sergei Karaganov, “Here’s why Russia must permanently abandon Europe and turn fully to Asia,” Russian International Affairs Council (blog), February 13, 2024, ➝.

Timothy Colton, “What Does Putin’s Conservatism Seek to Conserve?,” Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University (blog), January 17, 2022, ➝.

Alexander Gabuev, “Why China Is Sabotaging Ukraine,” Foreign Affairs, June 14, 2024, ➝.

GT Voice, “Russian Far East holds potential to cooperate with Heilongjiang,” Global Times, May 15, 2024, ➝.

New Silk Roads is a project by e-flux Architecture in collaboration with the Critical Media Lab at the Basel Academy of Art and Design FHNW and Noema Magazine (2024), and Aformal Academy with the support of Design Trust and Digital Earth (2020).