Carlos Fuentes, En esto creo (Mexico: Seix Barral, 2002), 313.

Plato, The Symposium, trans. Walter Hamilton (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1951), 211, d1-3.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book 1, chapter 2.

I. Blauberg, Diccionario Marxista de Filosofía (Mexico City: Ediciones de Cultura Popular, 1972).

Ibid., 29.

Ibid., 30.

Ibid., 21.

It’s worth mentioning that the Taino were eradicated by European invaders at the inception of the colonization of “America.” However, we still maintain their names, memories, and DNA in our veins.

Eric Hobsbawm, Bandits (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1969).

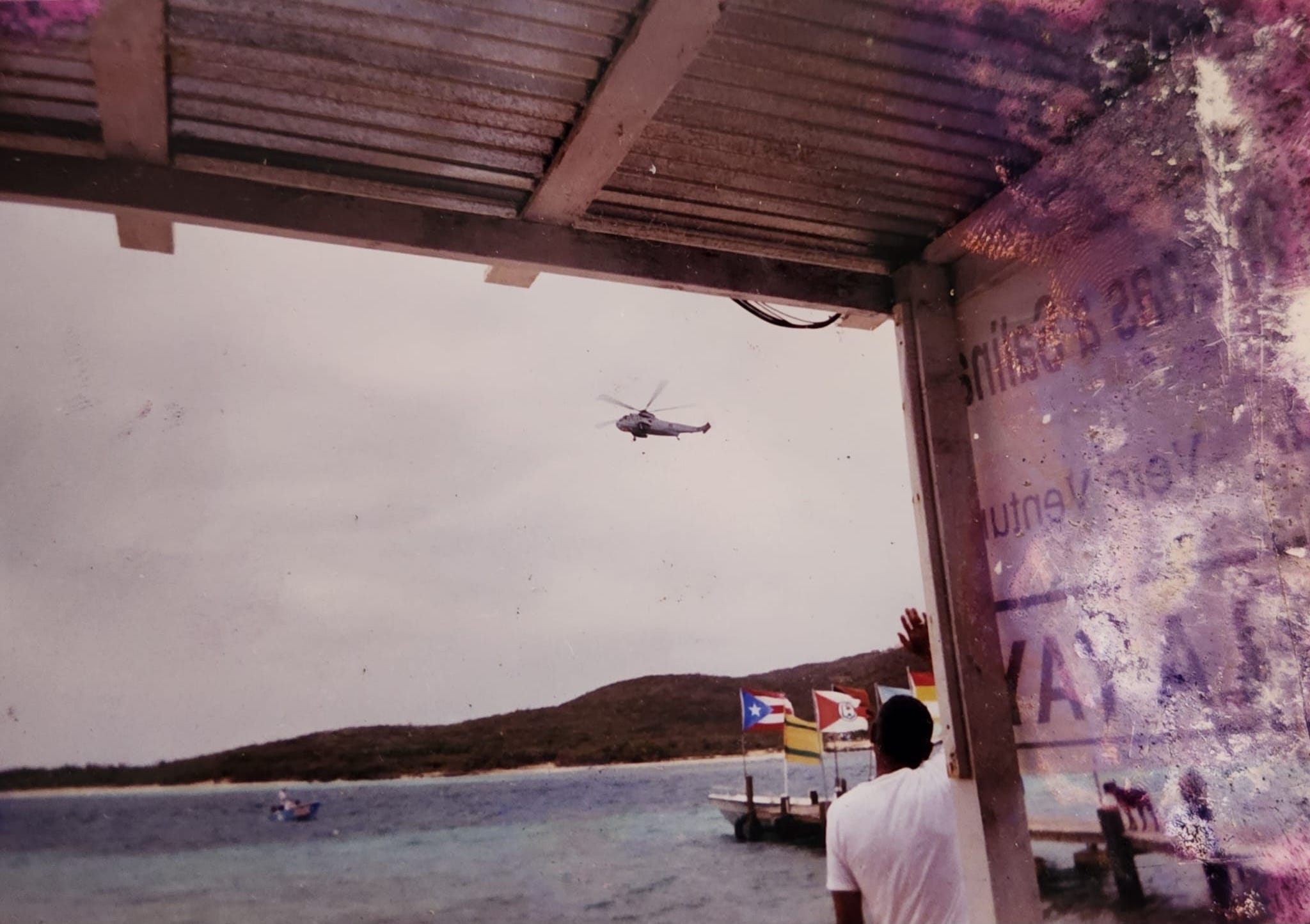

The plan’s name came from its ambition to remove and relocate even the buried dead from the cemeteries to the main island, so that the people would not even have the excuse of their dead, nor their memory, to return to the island.

As a result of an executive order issued by President Bill Clinton in 2001.

Robyn Wilson, "This remote Puerto Rico island is an idyllic Caribbean getaway – pristine beaches, lush rainforest and artisan rum," Independent, June 20, 2024, ➝.

José Saramago, Viaje a Portugal (Círculo de Leitores e Editorial Caminho, 1981).