September 15–18, 2022

Some documentary festivals prioritize the needs of the regional or international film industry, while others strive to present politically urgent and aesthetically groundbreaking nonfiction films to their audiences. Camden International Film Festival (CIFF) has been successfully combining these two strategies for almost two decades. This year’s program consisted of thirty-four feature-length and forty short films from forty-one countries spread around screening locations in Camden and Rockland. The premieres of big-budget documentary productions expected to entertain American movie goers as well as Netflix and HBO streamers—such as Sr (all works 2022 unless otherwise stated) by Chris Smith, Tamana Ayazi and Marcel Mettelsiefen’s In Her Hands, and Compassionate Spy by Steve James—were held at the Opera House in Camden, while the majority of artists’ films were featured at Rockland’s Strand Cinema and at a massive industrial dock turned into a movie theater. Following executive and artistic director Ben Fowlie’s injunction that “festivals must take risks” and senior programmer Milton Guillén’s invitation to accept the challenges cinema poses, the best films in this year’s iteration prompted audiences to reconsider what documentary cinema is and what it can do.

Katya Selenkina’s Detours (2021), the winner of this year’s Cinematic Vision Award, is an experimental documentary focused on a drug dealer who risks everything to hide packages across Moscow to be picked up by his anonymous online clients. The Russian filmmaker masterfully blends techniques of observation and reenactment to expose the peculiar ties between the Russian darknet and everyday life in the capital city. While following the day-to-day movements of Denis, the “treasure guy,” the film develops a singular perspective on urban landscapes, gradually instilling an unsettling sense of anxiety. These hideouts produce a sense of urban isolation and indicate the top-down surveillance of Moscow’s population. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing mobilization casts a new light on these unlawful activities. Instead of an acceptance speech, Selenkina, who recently fled Russia to avoid detention, delivered a heartfelt message demanding support for Ukraine and political reforms in Russia.

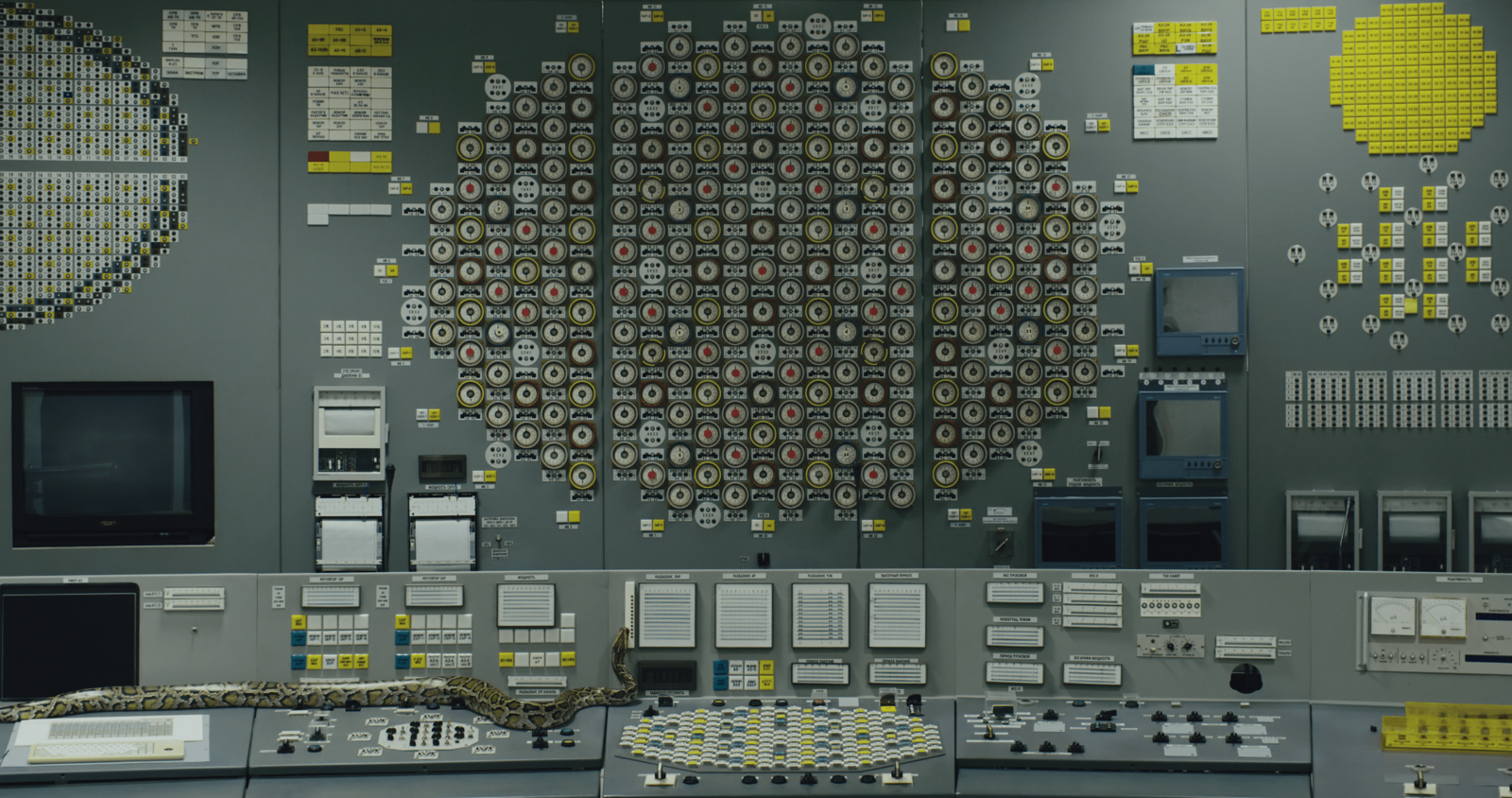

Also focused on invisible forms of state oppression and colonial power, Jumana Manna’s feature-length Foragers blends documentary and fiction to link the prohibition of wild harvesting (a Palestinian tradition) to the control mechanisms of the Israeli state. Emilija Škarnulytė’s Burial, meanwhile, looks at the present through the eyes of an archaeologist from the future. Portraying the dismantlement of a Lithuanian nuclear power plant, radioactive disposal sites in France, and the futuristic paintings of M.K. Čiurlionis, the film takes the viewer to impossible places. These images of empty reactors and subterranean tunnels make for a terrifying commentary on our situation: the film’s concluding shots of nuclear explosions recall Bruce Conner and the recently reignited fear of nuclear catastrophe.

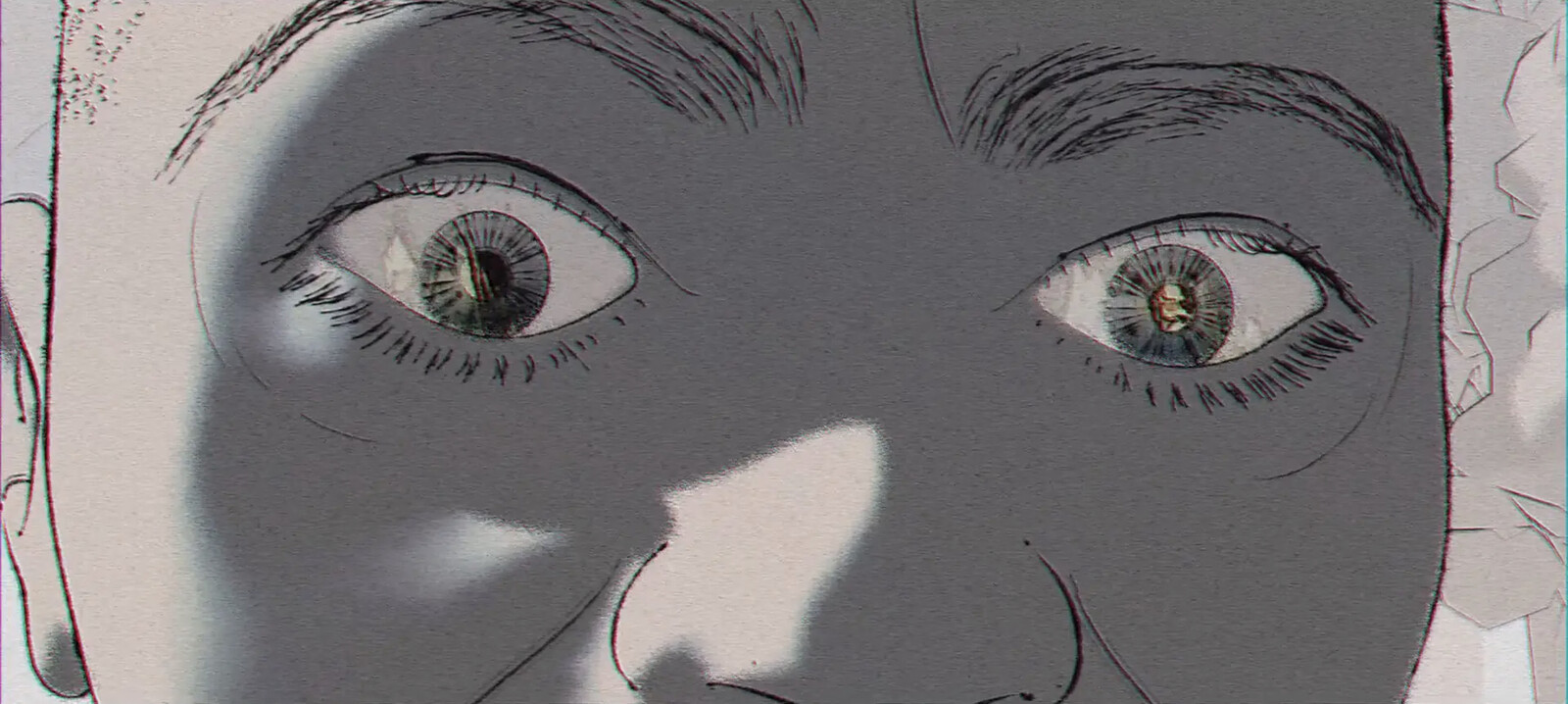

It Is Night in America, the first feature film by Brazilian artist Ana Vaz, is equally demanding. Evolving from a video installation commissioned by Fondazione In Between Art Film in Venice, it reveals the consequences of Brasília expanding urban infrastructure for the local wildlife. Like much of Vaz’s previous work, this contemplative film considers issues of social injustice without making explicit its critique. The camera is more interested in animals and their relation to the landscape—natural and artificial—than in characterization or didactics. As a result, what at first appears to be an expressionistic vision of de-familiarized urban space is, over the course of the film, transformed into a record of disturbing brutality and loneliness. At one point, the voiceover poses a question: “Are animals invading our cities or we are occupying their habitat?” The film might be seen as responding to the question.

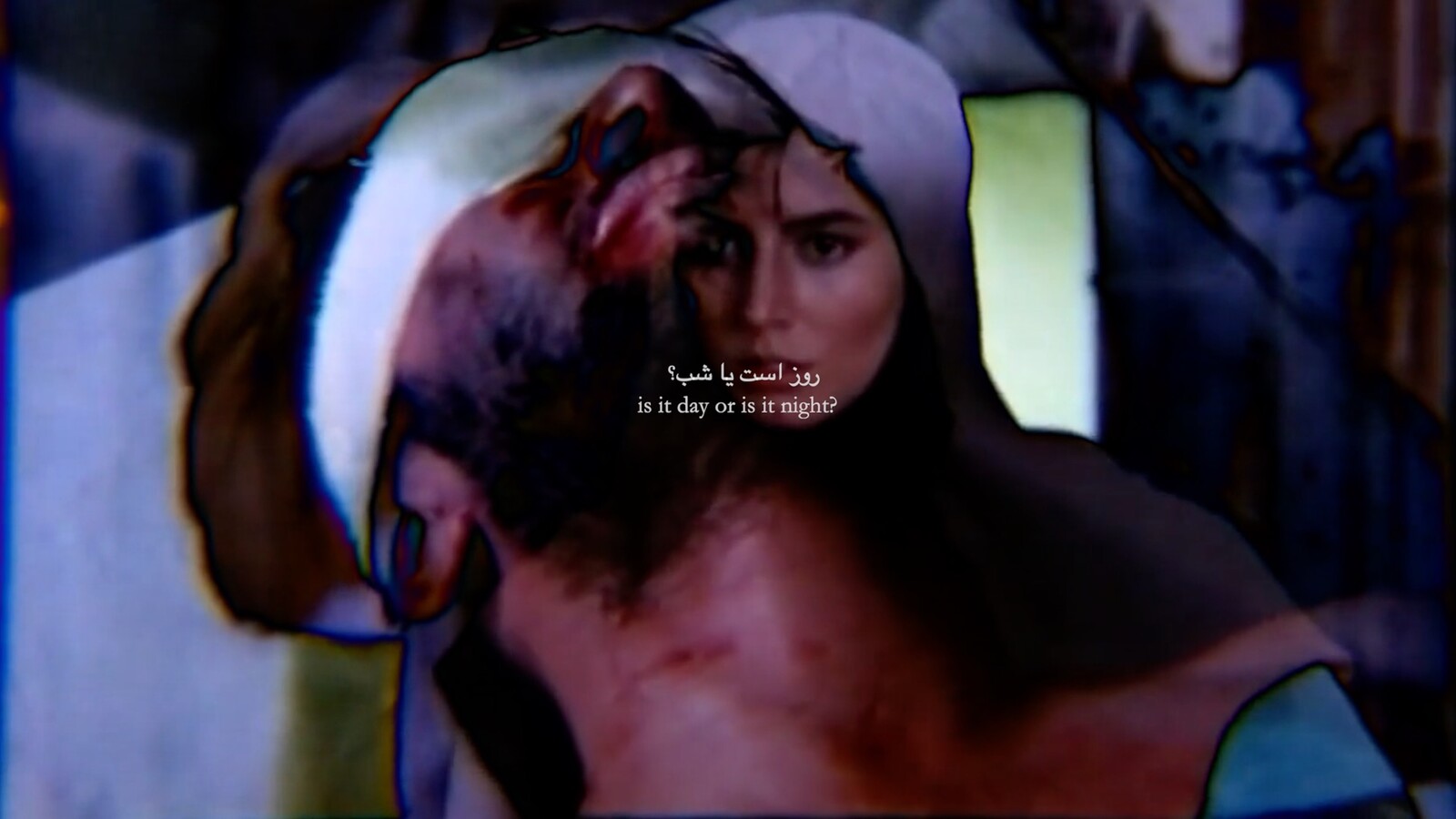

Just a few days before the start of the mass protests in support of women’s rights and freedoms in Iran, a poignant screening-performance by Iranian artist Maryam Tafakory challenged the depiction of women in post-revolutionary Iranian cinema. The Sun Quartet (2017), shown as part of a film installation by the artists’ collective Colectivo Los Ingrávidos, was a similarly lyrical exploration of the traumas of state violence in Mexico. The inclusion of these two works exemplifies the festival’s commitment to encompassing diverse and hybrid forms of nonfiction cinema. What’s more, CIFF has become an important meeting point for makers, critics, and curators of nonfiction film, thanks in part to Points North Forum, an annual event of presentations, masterclasses, and workshops for future generations of filmmakers.

“Cinema is a beacon,” reads this year’s CIFF’s tagline. The phrase underlines the increasing significance of nonfiction cinema at a time of rising authoritarianisms and ecological disaster. With its focus on politically outspoken and aesthetically radical forms of documentary that traverse the domains of cinema and contemporary art, as well as its efforts to sustain a diverse community of critical thinkers and practitioners, CIFF distinguishes itself from other American nonfiction film festivals by awakening social consciousness, stimulating critical thinking, and motivating political cooperation.