In the basement of a former Berlin crematorium, a small brass instrument sputters and hisses. The sculpture—Vartan Avakian’s Composition With A Recurring Sound (2016)—could be the baby cousin to a trumpet or saxophone. It is also the closest this group exhibition about rhythm gets to danceability. No surprise there. SAVVY is a space that emphasizes colloquy, meaning that its exhibitions and programs often seem less concerned with a central subject than that subject’s relation to a lived world. This exhibition concludes a program that extended into Berlin’s HAU theater and in 2016–2017 to Lagos, Düsseldorf, Harare, and Hamburg. It suggests an ad-hoc social nervous system, situating a willing viewer between the uncertainty of thinking and the affirmation of feeling.

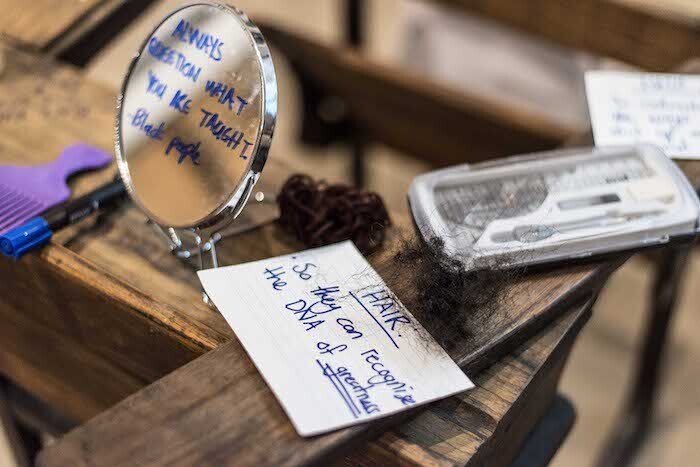

The exhibition’s conceit is that artists can elucidate the unseen rhythms that structure life, while the rest of us—by implication—are bewitched by so many abstractions and constructs: work, finance, love… Not suffering from humility, this theme becomes modestly obliging in function: a discursive matrix interlinking the work. IQhiya—a collective of South African women artists—has modeled the possibility of questioning power through lines of free-association inquiry that one might liken to beats in social space. Monday (2017) is made from school desks covered in reticula of objects and politically inquisitive notes, often joined with string, like mind maps searching revolution. A video shows the performance during which this scene was created, wherein the working artists are bathed in projected footage of a classroom uprising. If power takes root through the basic materiality of pedagogy, the work suggests, it can also be undone thereby.

In ways like this, the show’s claimed subject often dissolves into adjacent, potent themes. But if the words don’t always match the picture, it’s due to laudable effort at deepening conceptions of rhythm. In Allana Clarke’s video You Belong to Nothing and Nothing Belongs to You (2017), a finger peregrinates over skin. The epidermis is fractal-patterned, and the digit, echoing the listless meter of distracted fidgeting, underlines this show’s deference to the tempos of being alive.

For theoretical backup, SAVVY defers to the late philosopher Henri Lefebvre and the Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji. First Olatunji, with the show’s subtitle: we are all “the drum. Rhythm is the soul of life. The whole universe revolves in rhythm. Everything and every human action revolves in rhythm.” Lefebvre is then invoked to argue that artists might be a collective phenomenological organ, capable of listening to “a house, a street, a town as one listens to a symphony, an opera.”1 in Lefebvre, Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life (New York: Continum, 2004), 91.] Sprawlingly, this text implies that a sensitivity to rhythm might allow us to better understand everything from “the interrelations of space and time, memory, architecture and urban planning,” as mentioned in the exhibition’s introductory note, to Germany’s colonial history in Africa. A shade ambitious, maybe. But what counts in these claims is their provocative nature, energized precisely by the absence of emancipatory claims. I wonder: what might evil rhythm feel like? Would Mike Pence still be a stiff-legged bigot had he taken drum lessons as a child? Maybe. But then again, maybe not.

This exhibition plays a philosophical gambit, triggering wonderings that break down assumptions. Likewise Christian Nyampeta’s video Comment Vivre Ensemble (2015–ongoing), which documents candid chats with four—all male, regrettably—philosophers and theorists: Olivier Nyirubugara, Isaïe Nzeyimana, Obed Quinet Niyikiza, and Fabien Hagenimana. With this work, the gallery becomes a space of discourse. Thankfully, it is not only that. As a viewer slips through the other works, speech melts in languages of moving image; bodies and minds move at strange angles between plywood viewing stations, projections, and installations.

Walking figures largely, here, via abstracted cyanotypes from Délio Jasse (Terreno Ocupado [Occupied Terrain], 2014) and photographs by Akinbode Akinbiyi (Arrhythmic Narrations, 1984–2014). In both, framed photos accumulate like montages dictated by civic cadences. Jasse’s image also exemplifies how the show’s textual meanings often live a life apart from the work. The exhibition text elucidates the destruction wrought on Angolan life by postcolonial exploits, in particular the history of resource extraction. But to look at his photos is to be absorbed by gossamer blue images of people just going about their business, overlaid by translucent shapes, like visitations from an era of utopian abstraction. The pictures are gripping for their dreamy mixing of snapshot documentary and a kind of ad-hoc pictorialist intervention. But do they engage with the tough context we’ve been asked to consider? Maybe not. Amid such disconnects, the show feels like a discursive experiment: courting, like all worthwhile experiments, failure.

A similar contingency attends Fikret Atay’s charming video Paris Köyü [Paris Village] (2014). In a Turkish village, three young fellows build a minaret crossed with a miniature Eiffel Tower. It’s hard these days—though it always should have been—to not feel squeamish upon watching three masculine builders erect a building designed by a man, after consulting three fatherly elders, and one very male religious leader. Artwork, the truism goes, delivers latent meaning; here, the unintended memo is that constructing public space is a job best left to men. But the video is also a deeply worthwhile, contradictory fable: about compromises that ensue—maybe in both senses of the word—when signifiers of colonial power refuse to loosen their hold on the imagination.

Given all this, Eli Cortinas’s Quella che Cammina (2014) garnered added import, as a surreal montage navigating urbanity’s slighted dimensions. Therein, footage of an aging sex worker—borrowed from Carlo Lizzani’s contribution to the collective film L’amore in città [Love in the City] (1953)—is combined with shots of sculptures involving rotating eggish shapes and overflowing milk. A hushed voice muses on pleasure and responsibility: the body covers terrain and considers its imposed role as terrain of pleasure. This sort of conflict ripples through “That, Around Which The Universe Revolves,” an exhibition that opens thought to the body and the body to thought, as all efficacious exhibitions should.

Henri Lefebvre and Catherine Régulier, “The Rhythmanalytical Project,” [1985