Marianna Simnett’s videos, currently on show at FACT Liverpool, are played on a continuous loop, so you can’t tell how they begin. The same blonde girl is sent on hallucinatory adventures in The Udder (2014) and Blood (2015): inside a cow’s udder, around an Albanian mountain, through agricultural machinery, and up her own nose. The narratives are, in both senses, loopy, and the videos are screened in a square room on adjacent walls: while you watch one, the visuals of the other flicker in the corner of your eye. The effect is disorientating. Viewers were squirming.

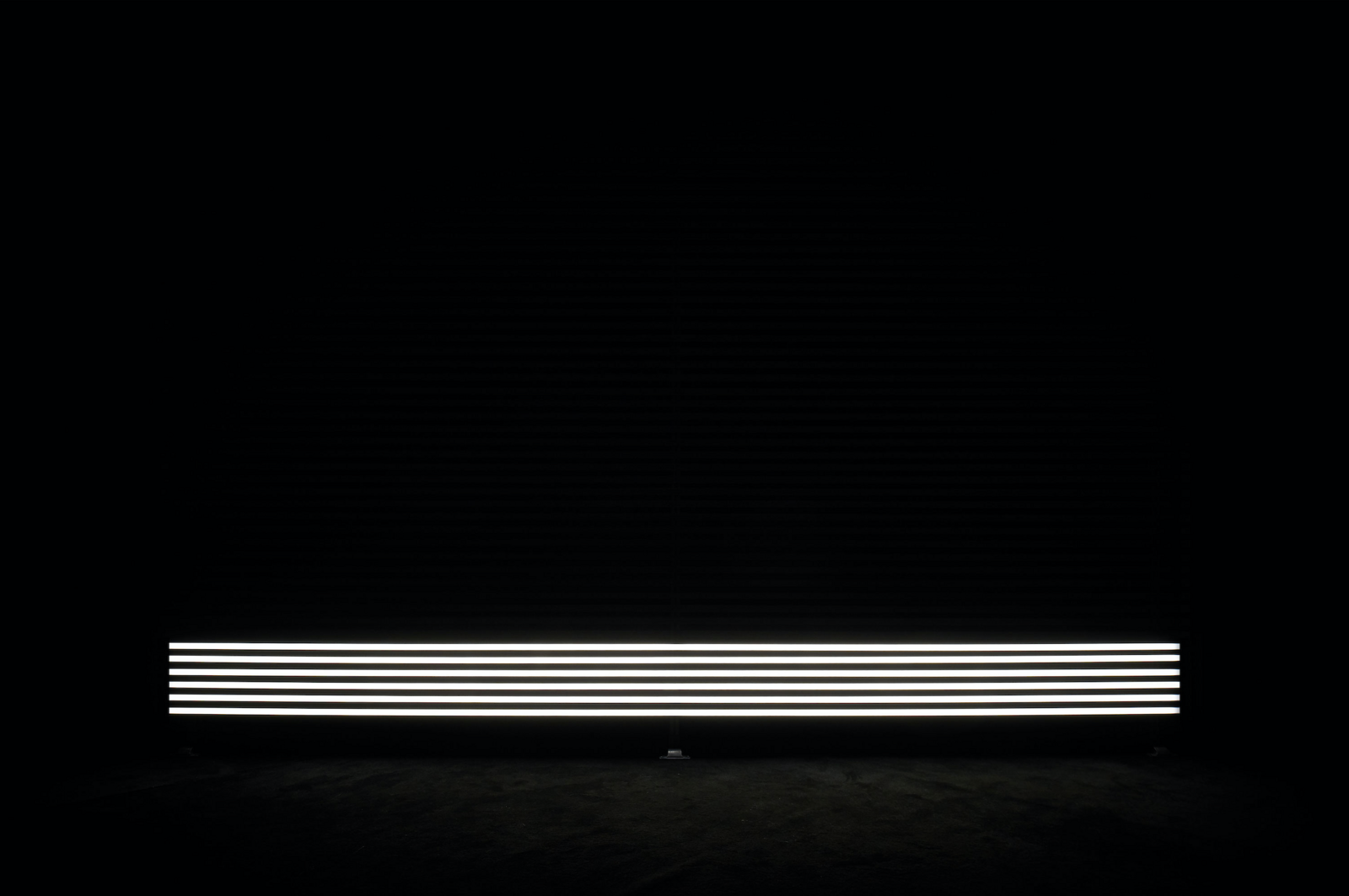

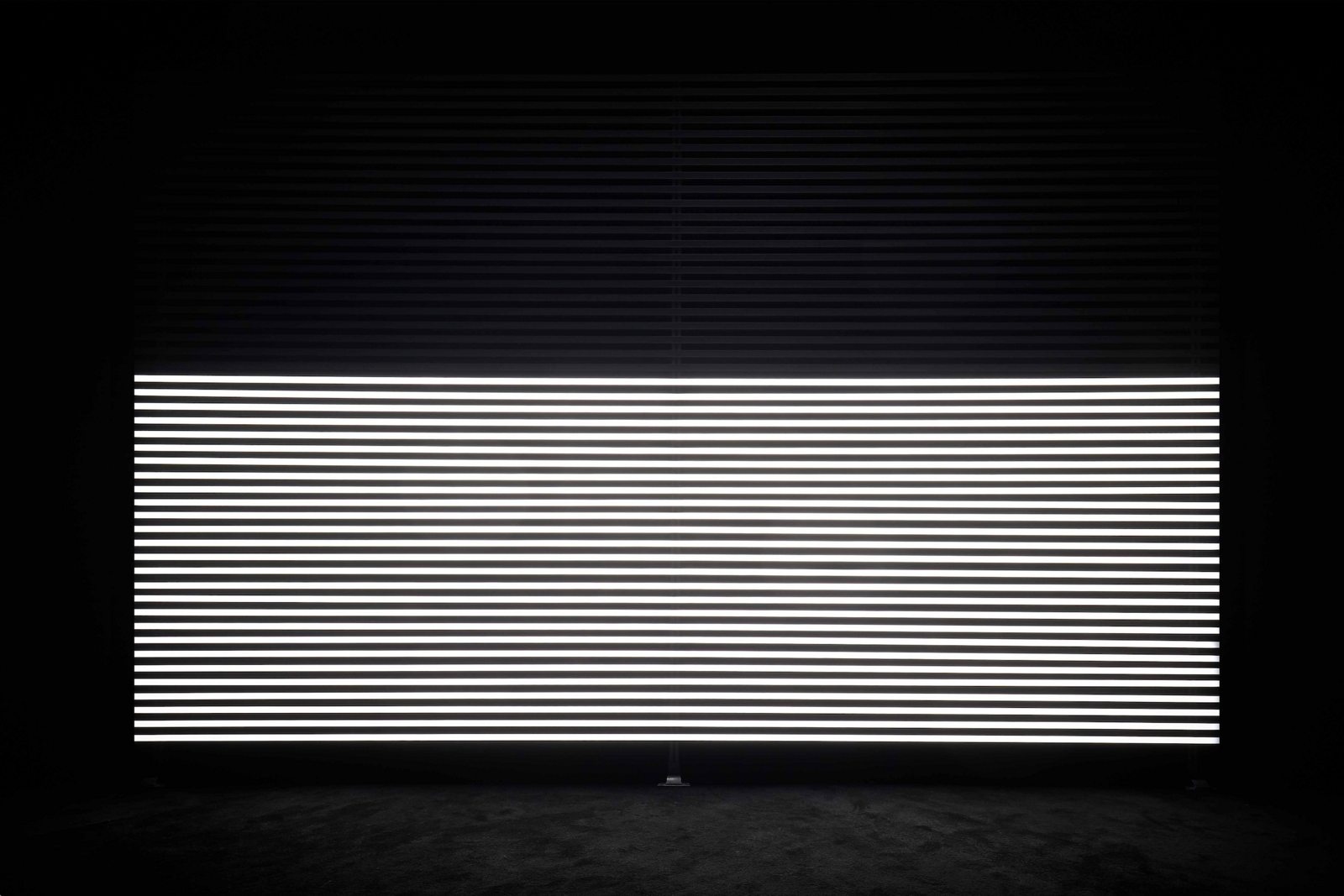

Simnett’s videos are notoriously visceral. The Udder shows the dissection of a cow’s teat; Blood gives a keyhole-view of a brutal operation, and has two personified nose-bones gnawing on a septum, complete with gristly slurping sounds. But Simnett’s third work in the exhibition challenges in a different way. Faint with Light (2016) is a room with a large panel of white striplights which flash, irregularly, in correspondence with a reverberating soundtrack of the artist hyperventilating violently until she passes out. It’s physically uncomfortable in there. The show asks how far your body is willing to go, whether it’s because Blood makes you feel squeamish, or because Faint with Light’s audio literally makes your innards vibrate. It is a strange experience to stand in the small room for a few minutes, gritting your teeth and screwing up your eyes against the glare. I wondered what I was doing. Why would a person choose to stand in unbearable light, listening to a recording of another person harming herself? Out of interest?

One of the interesting things about Simnett’s work is this force of aversion to what it is doing. To see a scalpel applied to an udder is painful, even though I’ve been implicated in agricultural commerce since before birth. It’s uncomfortable to look at the gelid interior of a nose, even though I am used to wearing one on my face. Simnett has spoken about her desire to draw political and ideological thought into the reality of the bodies we live in. Increasingly, it is apparent that these bodies are out of hand. Any number of phenomena— Fukushima, Zika, the mouse with the ear on its back—make it clear that people have erratic and unpredictable control over lively, trans-corporeal agencies, but it isn’t always easy to relate scientific or philosophical insights back to normal life. The fragments of ordinariness and hope which punctuate Simnett’s work become pressured and touching. A group of men quietly rehash a football game around a living-room table. Two boys blow bubbles into their chocolate milk. Even that which seems psychedelic—they happen to be drinking milk inside a chamber of a cow’s udder—is often a reasonable expression of bodily reality. (The fact that humans drink milk is what keeps udders full, and constantly refilling.)

The Udder draws parallels between the hygiene of mass-production dairy farming and female chastity in a similarly grounded but freaky way. A farmer warns her daughter to play inside the house, where she’s safe from strange men, and in the barn, the cows are sprayed with antiseptic to keep out germs. Parts of the dialogue draw on John Milton’s 1634 masque Comus—a kind of musical, celebrating the power of chastity, written for an aristocrat’s party. Simnett creates new meanings by using its relationship to the body as something both despised (a “corporal rind”) and fetishized as the bearer of chastity. The fact that Comus is so old and so alien helps Simnett make her subjects strange, which is where the video’s strength lies. The Udder is a playful way to say the other. In Blood, there is another kind of excavation and reclamation at work in its play on the idea, developed by Wilhelm Fliess and embraced by Sigmund Freud, that nasal surgery could cure hysteria.

Simnett’s work at FACT is shown alongside Ericka Beckman’s 1980s and ’90s films, which draw on video games and fairy tales. What comes across powerfully from both artists’ work is the fact that simply contaminating one narrative with another can be disturbing. Different languages and registers could be intimate to one person, but still clang when put next to one another in public. It is strange to hear a textbook definition of mastitis given in response to a seductive compliment, or to see the fairy-tale princess in the kind of pixelated landscape where she might bump into a Mario Brother. The experience of this dissonance made me feel that overlooking is a more willful process than it seems. I thought of W. G. Sebald, writing about the fake grass that surrounds the cuts of meat in a butcher’s shop—plastic meadows designed to make the customer feel that her steak is enjoying the refrigerator, using an image which seems almost deliberately inept. The fake grass, for Sebald, shows “how strongly we desire absolution and how cheap we have always bought it.”1 Like Simnett’s work in its emphatic drawing-together of the wrong contexts, the spectacle is both humorous and sad—painfully funny—which is one way to redefine hysteria.

I found Beckman’s work less troubling, partly because it so suited its retro feel. Graphics date quickly, and 1980s Cinderella is all eyeshadow and leggings. I had to remind myself that these features which now look like vintage details were relatively neutral at the time—they weren’t pointed references to a culture in which feminist fairy-tales were a new thing. Coming to Simnett’s work upstairs afterward, I wondered whether the texture of her videos will date in the same way, and what will happen to them if they do. Maybe in 30 years’ time The Udder and Blood will look like period pieces in the sense that they address truths which are already palatable. I hope so. Maybe in 400 years’ time Simnett’s videos will seem as radically strange as Comus, their vocabulary open to be reclaimed for purposes which are unspeakable now.

W. G. Sebald, Campo Santo, translated by Anthea Bell and edited by Sven Meyer (London: Penguin, 2006), 43–44.

%20Marianna%20Simnett,%20The%20Udder,%202014.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby%205.jpg,1600)

%20Left_%20Marianna%20Simnett,%20The%20Udder%202014.%20Right_%20Marianna%20Simnett,%20Blood%202015.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby(1).jpg,1600)

%20Left_%20Marianna%20Simnett,%20The%20Udder%202014.%20Right_%20Marianna%20Simnett,%20Blood%202015.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby.jpg,1600)

%20Marianna%20Simnett,%20Blood%202015.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby%207.jpg,1600)

%20Marianna%20Simnett,%20The%20Udder%202014.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby%207.jpg,1600)

%20Marianna%20SImnett,%20Faint%20With%20Light%202016.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby.jpg,1600)

%20Ericka%20Beckman,%20Cinderella%201986.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby(2).jpg,1600)

%20Ericka%20Beckman,%20Cinderella%201986.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby%201.jpg,1600)

%20Ericka%20Beckman,%20Hiatus%201999_2015.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20(c)%20Rob%20Battersby(1).jpg,1600)

%20Ericka%20Beckman,%20Hiatus%201999_2015.%20Installation%20view%20at%20FACT%20©Rob%20Battersby.jpg,1600)