“Let me tell you about my mother” is a famous line from Blade Runner (1982), the iconic movie that wonders about the violent intersections of life and technology and what really makes us human. A little over a decade later, at a time when technology’s coloring of the human experience had exponentially intensified, those words were recycled as a sample in “Aftermath,” a song off Tricky’s debut, genre-defying album, Maxinquaye (1995), which was named for his mother, Maxine Quaye, who died of suicide when he was little. Now fast-forward nearly 15 years after that, and consider Jacolby Satterwhite’s exhibition “You’re at home,” which rolls up everything I’ve just written about into a dizzying fractal pattern along with a manifold of other references, sounds, and iconography in which, indeed, the artist tells us all about his mother.

Tricky has said his mother used to write poems but had no place to put them. Patricia Satterwhite, too, was an artist without a public, without a means of access to the infrastructure and institutions that would have made her the star Jacolby says she dreamed of becoming. Before she died in 2016, she had lived with schizophrenia. Throughout her life she incessantly wrote pop lyrics in big letters on unlined white pages and sang them into a cassette recorder; she drew pages and pages and pages worth of inventions that she wanted to fabricate and sell on a home-shopping TV network. Jacolby has long used Patricia’s work as raw material, incorporating her drawings in earlier animated videos like Country Ball (2012) or the multipart Reifying Desire (2012–14), which he describes as a collaboration with her. This exhibition is something like the apotheosis of that collaboration.

Nestled inside the sensory overload of projections, digital screens, sparkling disco balls, hyper wallpapers, and ambiguous synthetic objects at Pioneer Works is a spare white room in which the son has tenderly and attentively displayed a series of the mother’s drawings, framed on the walls, and lyrics, laid under plexiglass on a simple wooden shelf. The title of his exhibition is taken from one of Patricia’s songs, in which home is a recurring theme. The room serves as something like the motherboard for the rest of the exhibition, as if her sketched and written dreams were exercising commands that are somehow realized in three-dimensional space outside of those white walls.

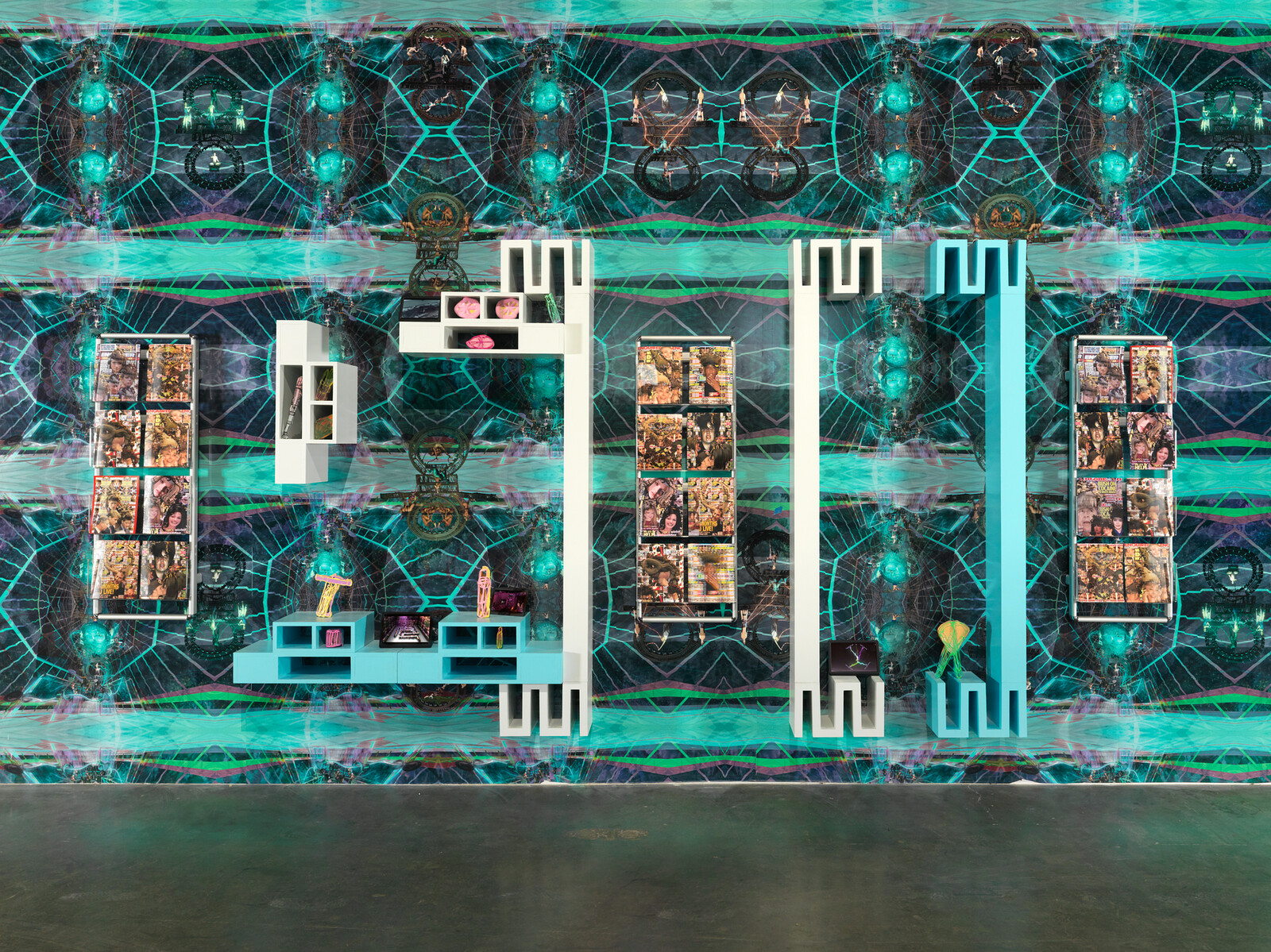

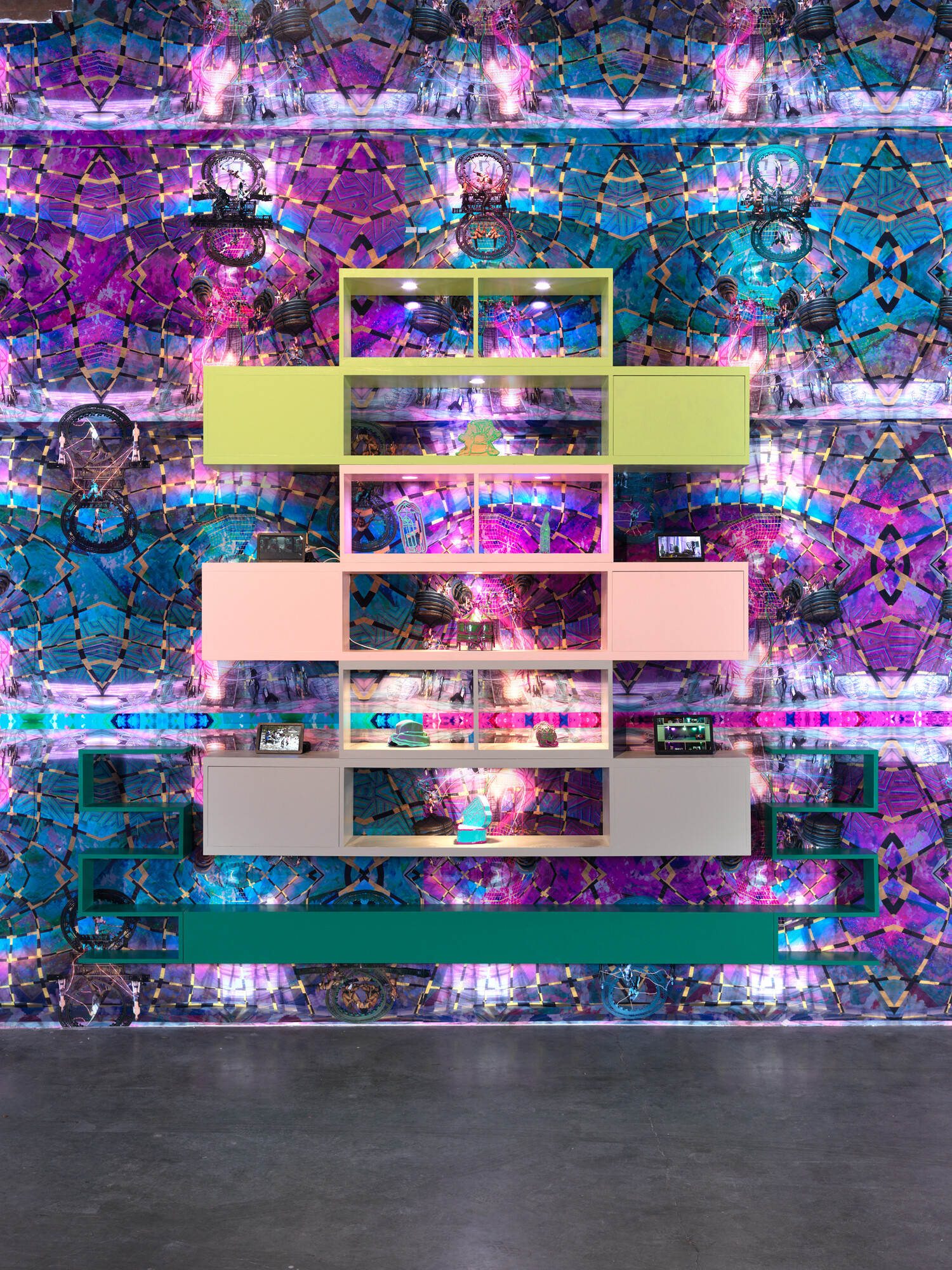

Patricia’s songs have become the basis of an electronic album, Love Will Find A Way Home, by Jacolby’s band PAT (which the artist says is an explicit nod to Maxinquaye) that visitors can listen to and experience spatially via VR headsets at Tower Records–like listening stations in the main gallery. Also in this central space is a wall covered in several kinds of wallpaper that seem to be inspired by a note of hers, here electrically hued and covered in hypnotically repeating scenes grabbed from Jacolby’s animated videos. Over the wallpaper is an assemblage of shelves and supports that hold a series of 3D-printed renderings of Patricia’s designs, displayed alongside the occasional tiny screen (another of her ideas was “art showing computer screens,” which, based on her sketch, appeared to be a little portable electronic display, like today’s digital picture frames). One of these screens shows children dancing, jubilant and free, their infectious joy and rhythm moving the adults nearby to join in: it’s footage from a VHS recording of a mother’s-day cookout Jacolby’s family threw in 1989 (footage that was also a foundational material for Country Ball).

Other screens display animations that prefigure the work at the heart of the show, a two-channel video called Birds in Paradise (2017–19). Dizzying and delirious, it combines scenes of Jacolby dancing alone in the streets, with vast digitally animated passages in which a multitude of avatars move in some sort of industrial coliseum from a parallel universe, with images of a cowboy on a flying horse being baptized by a mermaid and the occasional drone footage of forest fires. There’s a scene where Jacolby’s body is pulled up into the air by a rope; he says the image was inspired by a Nigerian Yoruba Gelede ritual—the Gelede being, appropriately enough, a celebration of mothers.

The artist has noted in interviews that because it is a black body that gets hoisted up, viewers might assume that this might be a scene of violence—Jacolby’s identity as a queer black man in America is one that carries with it an overdetermined politics of representation. Because “You’re at home” is essentially a self-portrait in a swirling and immersive post-internet form, those politics of identity are also part of it, aspects of which I, as a white cisgender heterosexual viewer, may miss. But I do recognize the project’s motivating tension of love, longing, and loss for and of the one who was supposed to take care of you, the knowledge that you will always, inevitably, have a vision colored by hers. And I recognize the work as a self-portrait that is utterly irresolvable, a picture of the artist in flux, constantly recombining his own embodied memories with the imprints of all the cultural objects that come to us through technologically mediated forms. And I recognize an awareness of our apocalyptic condition always flickering at the fringes of consciousness. When Maxinquaye came out, Ian Penman wrote about it best. “Everything is velocity and disappearance and mutation,” he said; writing on artists like Tricky, Penman wanted “to reclaim what is truly human (memory, lack, doubt, danger) through and in technology, when it otherwise threatens to evaporate in the blurry oasis of modern marketing.”1 Jacolby’s exhibition does something like that. It is, in all its digital excesses, truly human, brimming with all of the human’s angelic and ghostly and fulsome riot.

Ian Penman, “Black Secret Tricknology,” The Wire vol. 133 (March 1995), see http://www.moon-palace.de/tricky/wire95.html.