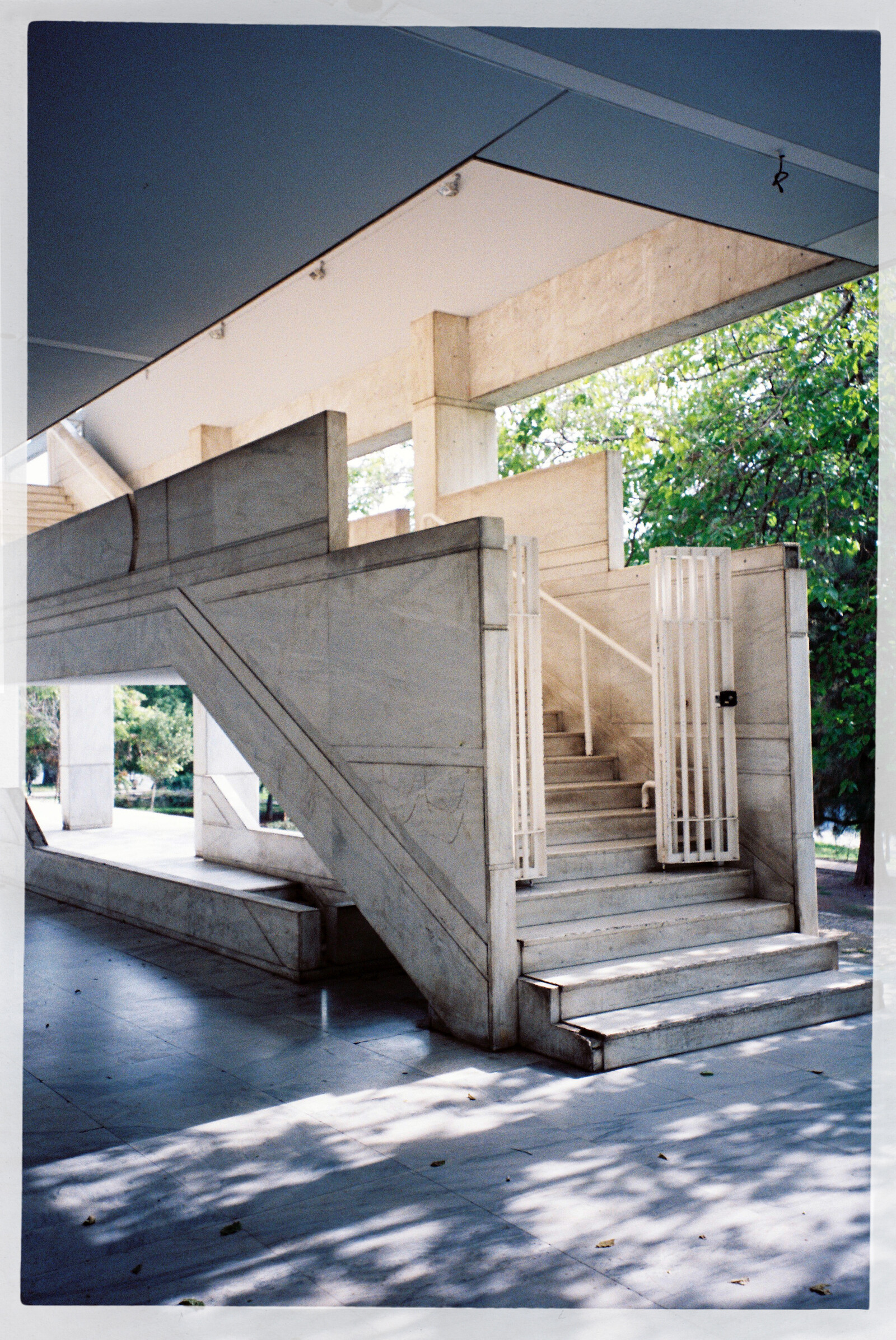

In 1894, just a year after Prime Minister Charilaos Trikoupis had declared Greece bankrupt, Athens was chosen to host the first modern Olympics. The occasion demanded the total refurbishment of the Panathenaic Stadium, a venue used for athletic competitions since ancient times. As the city embarked on this expensive endeavor, someone (the Olympic committee, mayor, or king, according to different versions of the story) posed the question “Ποιος θα πληρώσει το μάρμαρο;” [Who is going to pay for the marble?] In the decades since, the ancient Greek word has come to acquire a new significance in the modern vernacular: that of damage.

Marble in Metamorphosis, a book which “contemplates the physical and cultural life of marble,” is published by an Australian property development company active in Athens. Much like a mockup apartment, everything about this object is designed to showcase the company’s taste: an essay by Rachel Cusk, Chris Kontos’s sleek photographs of Athens and the island of Tinos, excerpts from poems by major Greek poets Giorgos Seferis and Yannis Ritsos, and a poetic afterword by Nadine Monem, all make for a chokehold of beauty. Yet, in recent years, public policies that prioritise property over home, investment over sanctuary, and the reduction of a country’s culture to a series of greatest—read, most profitable—hits have ensured that practices of refinement, such as those this company promotes, are vehicles that contribute to Athens and the islands becoming increasingly unaffordable, especially for those reliant on Greek wages.

Using language that makes employment sound like charity, the publisher states that it is “seeking to advocate for the city and its inhabitants. To support it and them in engaging with opportunities, post economic crisis, in gentle and appropriate ways.” The solutions it seems to be suggesting are mostly focused on safeguarding a certain aesthetic standard. Laudable as this intent may be, it is hardly enough to address current realities. If the title was reversed to Metamorphosis in Marble, there would at least be some hint at an awareness of the threats that development poses to urban and natural ecosystems, and the statement would sound less sly. Instead, the book foregrounds deceased poets as “contributors,” instead of the authors of the long, detailed captions which accompany Kontos’s photographs, and which make up about half the book’s volume (offering an encyclopaedic account of the city and the islands’ connections to marble). Perhaps the poets are willed into being themselves, much as the publisher describes “property development [as] the willing of architecture into being.” Resurrection by fountainhead.

Prompted by her annoyance with the noise of construction work held near her temporary residence on a Greek island, Cusk writes that “more people live cosseted in the vague belief that their existence and the work that they do are essentially non-destructive, but hardly anyone in our era can really say that about themselves. These days, the very condition of being alive represents an act of extortion: it is unavoidable.” In an expertly articulated preemptive strike, she sentences herself—and anyone who might be wondering why a writer of her caliber is writing for a property development company—guilty by default. But to wonder isn’t to cast the first stone, and while the condition of being alive necessarily entails expenditure and environmental footprint, the degree varies wildly.

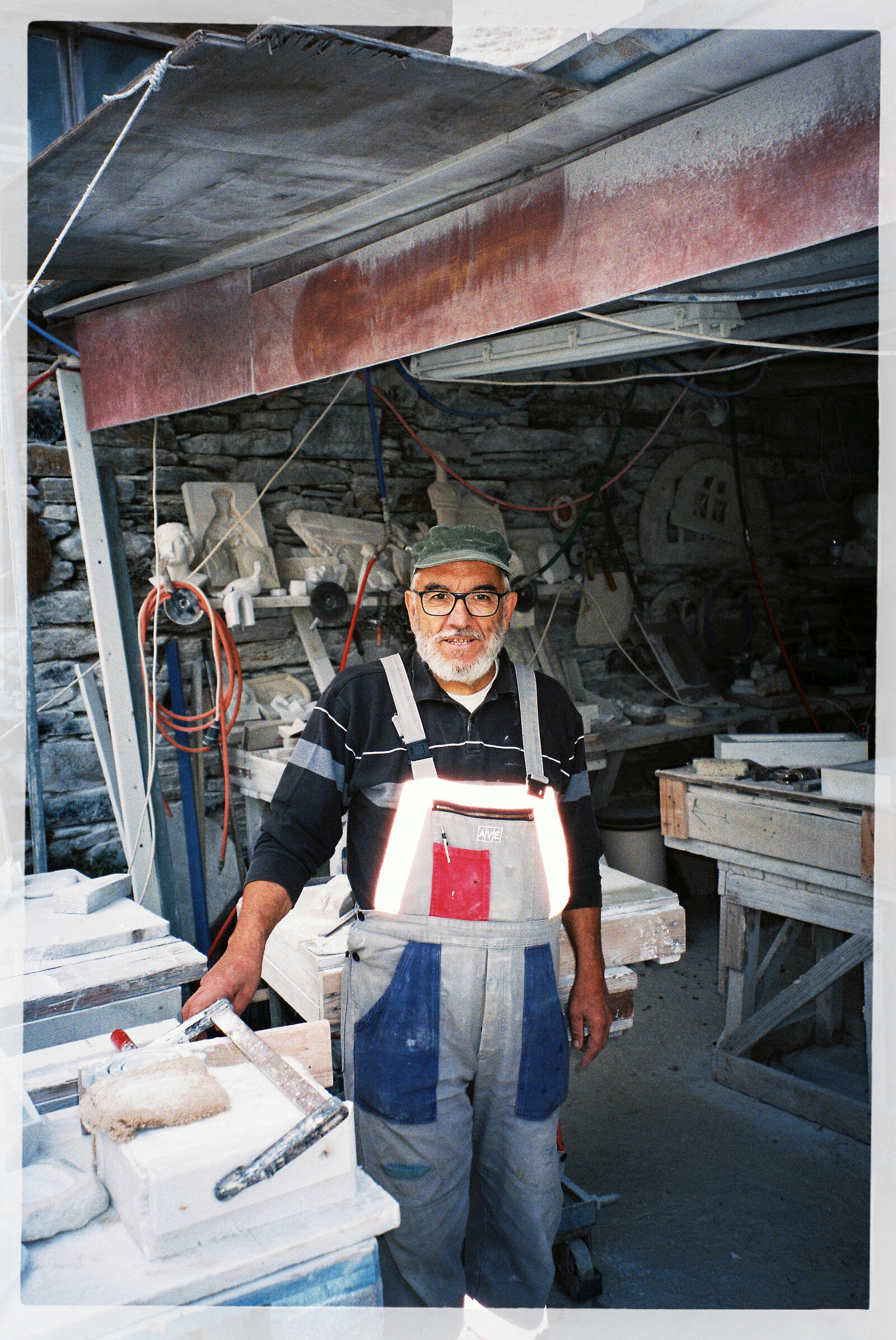

Cusk seems to be writing from an uncomfortable place, and it makes for a confusing read. Yet here we are, talking about marble, in an essay that seems to fold under the weight of its subject. Poetic reflections on the mineral’s versatility, its endurance as material and as symbol of status, turn into an exploration of the stone’s moral universe as it passes through the hands of artists and dictators, Tinian stonemasons, miners and developers. Sentences are delivered as moral imperatives, but the writer’s uneasiness verges on apologia, assimilating the expectation of punishment deep within the writing.

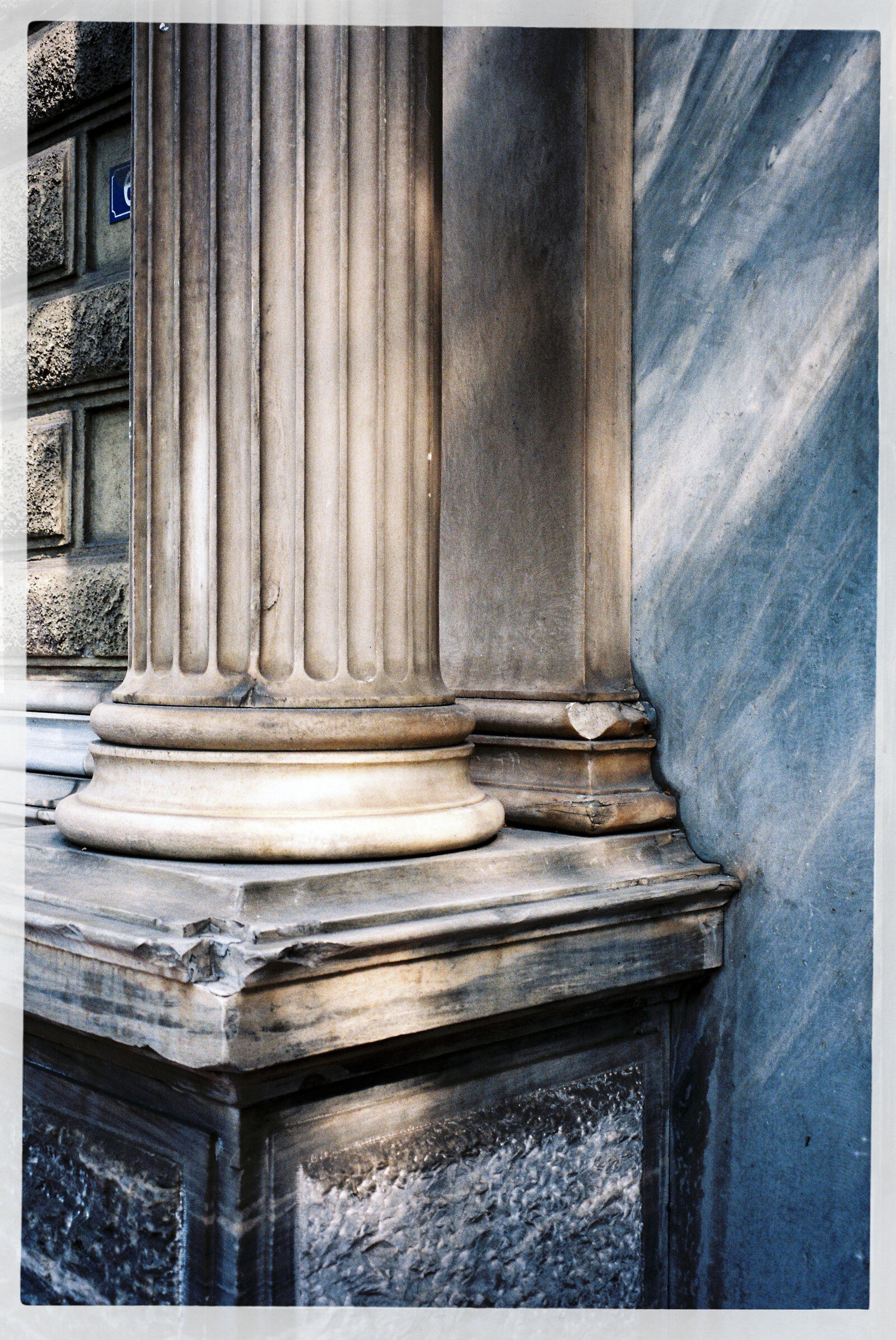

The essay ends with a description of four white marble columns that “look like four fingers of light” gazing out at sea. It is an image so evocative, so purposely incomplete that one wishes the night, or some soft mythic creature, would descend upon them and in their unison make a luminous, majestic spill all over the apartment.

But then someone would have to clean it up.