Why did the chicken cross the road? I don’t know—but Allison Katz has some suggestions. There are chickens aplenty in “Artery,” a show of 30 works, the majority new, by the Canadian painter. The other side (2021) is a painting of a cockerel in motion that recalls Eadweard Muybridge, the work hung across two freestanding walls so the bird seems to be surmounting the gap between them.1 Grains of rice—a kind of chicken feed, presumably—are scattered across the canvas surface, stuck on and around the golden animal. Despite the bird’s strut, it’s unclear—given the yellow plumage and blue-feathered head—whether what we are looking at is the result of Katz painting a chicken (or a photo of a chicken), or of her painting a chicken-shaped ornament; whether this painting is a representation, in other words, or a representation of a representation.

This quandary seems answered in The Cockfather (2021), a painting titled like a hipster fried chicken joint, but which in fact shows a kitschy egg holder in the shape of a cock in which are placed three eggs, the neck of the apparently misgendered bird (it is hens who normally warm eggs) forming a handle. This plumed porcelain soul is not shown sitting amidst tea and toast, but in what seems to be a cave, the chicken’s shadow looming large on the dark walls behind it. The chickens in Posterchild (2021), by contrast, are evidently painted from life. Or rather, from a photograph of two real-life birds crossing a slightly curving road, uploaded to Wikipedia in 2012 by a user called Cleopatra to illustrate the entry titled “Why did the chicken cross the road?” It shares the canvas with several other small, disparate scenes contained in rectangular windows, overlapping like a pile of postcards. Among these are two figures in silhouette; a face like that belonging to the Green Man of folklore; a suburban house; and two arched foot tunnels, the dividing wall between the passages hanging like the pendulous uvula in the back of the throat. What connects these? No idea. Joke’s on me.

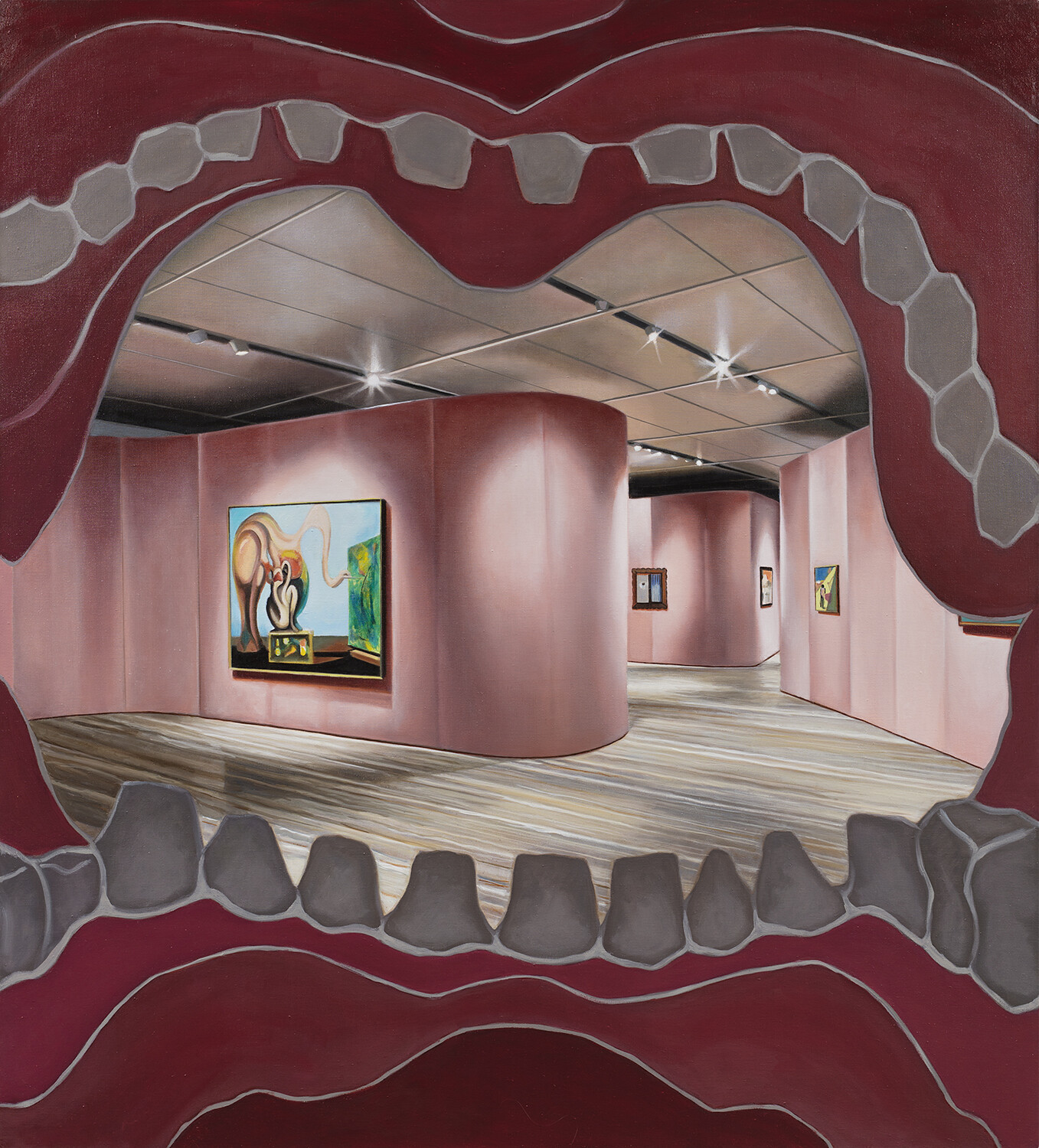

Like the well-crafted call-back of a good stand-up, that last image is riffed upon in the final gallery. Arranged in an arrow-like formation are six free-standing walls. On each is a painting that positions the viewer inside a mouth looking outwards. In the foreground of each painting are teeth and gums; beyond the pink-red caverns are a variety of—again wide-ranging and seemingly unconnected—scenes. The first of these is, naturally, an ornamental cockerel (akin to a little Rooster of Barcelos souvenir one might buy in a Lisbon tourist shop). The others variously depict two faces gliding in for a kiss; a strange, oily-looking cat; a woman kneeling, her legs demure to one side (a self-portrait, the image a 2021 advert in which Katz appeared for the Miu Miu fashion brand); and an art gallery hung with work by William N. Copley, of whose painterly lineage of poppy surrealism Katz could be considered a part. On the opposite side of each wall are hung paintings of cabbages, dated between 2013 and 2020, each with a silhouette profile of a man’s face looking towards these alluring vegetable still-lives. Such non-sequiturs are, I now realise, to be expected from this exhibition; all the same, these pairings have the feel of a delightful burlesque.

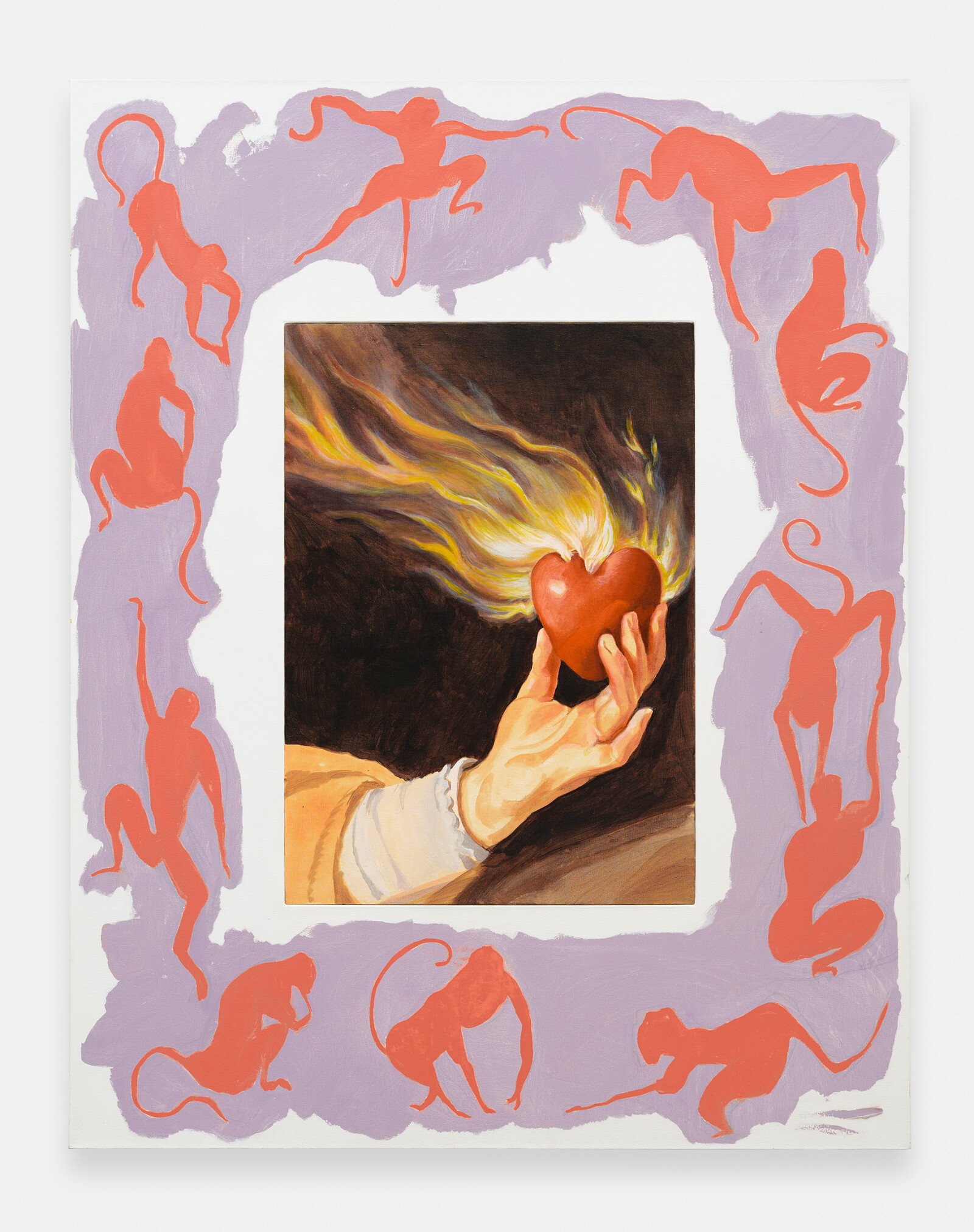

Katz’s art operates in the mode of pun- or riddle-making. An object or image is given double or multiple meanings, the viewer either brought into the fold as they follow whatever semiotic acrobatics the artist performs for them, or left to decipher the narrative themselves. Despite frequently making me laugh, however, Katz’s paintings aren’t really jokes per se. More akin to nonsense literature in the heritage of Edward Lear or Mother Goose, they don’t seek the natural conclusion of a punchline. They lead you on a merry dance, clowning your senses, poking at memories and learned responses, providing symbols but whipping away the symbolism, refusing neat narrative. Katz’s incongruous imagery proves a refreshing antidote to the dogmatism that prevails in art—and beyond—today.

Because they always depict roosters, the artist has referred to this series of works as “cock paintings”