Curator Joanna Warsza titled the 2018 edition of Public Art Munich (PAM) “Game Changers,” choosing to focus the festival on 20 live events, shifting the definition of public from sites to subjects. In lieu of outdoor sculptures there are events, and in place of a map a schedule. Conceptualizing the festival, Warsza focused on three historical moments that took place in Munich: the proclamation of the Bavarian Soviet Republic in 1919 (established and disestablished within less than 30 days); the inauguration of the Olympic Stadium ahead of the 1972 games (a moment of optimism shattered when Palestinian organization Black September killed 11 Israeli athletes and a German police officer); and the welcoming of refugees at the Munich train station in summer 2015. These events are game changers, according to Warsza—short episodes that affect societies years later.

The ideologies that underlie these three events—radical politics, short-lived revolution, long-standing struggle, and the lasting aftermaths thereof—inform the commissions for PAM, which address different political, historical, and social questions from numerous angles. On the festival’s website is a glossary of terms, from “Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany” to “Relational Specificity,” “datafication,” and “countersurveillances.” It’s an ambitious framework for what is essentially a slow and small festival, where over three months there are usually only one or two initiatives per week. They range from drawing in public (Dan Perjovschi is doing three live painting sessions in which he takes questions from the audience and draws his trademark political cartoons) to film screenings (such as Alexander Kluge’s Winter of Love [2018], about the 1968 student protests in Munich), talks (by theorist Chantal Mouffe and curator Maria Lind, for example), and an acoustic intervention by Lawrence Abu Hamdan in the studios of the CIA-funded former radio station Radio Free Europe. The city’s Cold War history is further reflected in Michaela Melián’s 24-hour performance Music from a Frontier Town, in which she plays from 1600 vinyl records left behind when the United States Information Agency stopped funding the Amerikahaus, a chain of institutions across Germany and Austria meant to expose local citizens to American culture and politics, and in Foundation Stone, an audio installation by Cana Bilir-Meier at the local Freimann Mosque. Playing in and outside the building, which was once supported by the CIA in an attempt to politicize Islam against communism, Bilir-Meier’s work focuses on the stories of migrants who shaped the mosque and its community. Comprising a series of oral histories, it includes accounts of the building’s Turkish architects (told by their daughters) and the memories of Bilir-Meier’s mother, who worked at the mosque as a family therapist.

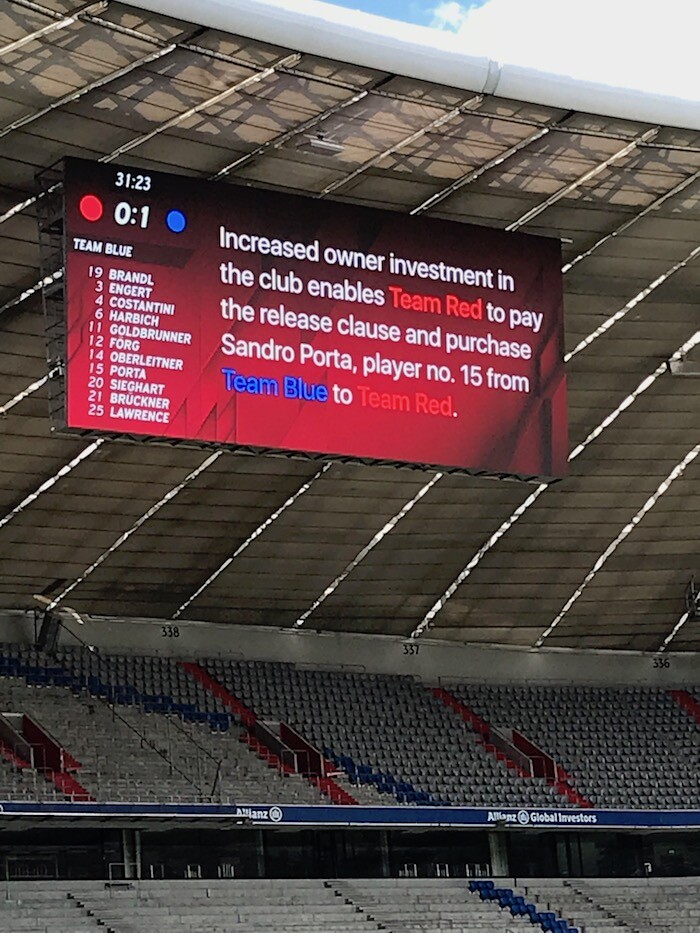

This variety means art is shown in places locals may have never been to—the radio station’s studios, for example, are now the library of the university’s media department; the Amerikahaus is now the Bavarian Center for Transatlantic Relations—or always dreamed of visiting. At the Allianz Arena, home of FC Bayern Munich, who won the seven last German league titles in a row, Jonas Lund and Alexandra Pirici staged N Football, a football game featuring the Bayern youth teams. Divided into two mixed-gender teams, boys and girls from the under-16 and under-17 age groups played a game interrupted every few minutes according to a set of regulations designed by the artists. When a player scored, a “collective credit” appeared on the massive screens, acknowledging the forward who netted the ball as well as those who assisted. It countered the fact that, despite being a team sport, football is largely discussed and represented in terms of individual winners. For about 20 minutes, both teams played on just half the pitch, with one team attacking and the other defending, before switching turns—a comment on the financial discrepancies inherent to football, where global brands supported by oil-rich states and oligarchs can meet local clubs which have no chance of winning unless they play defensively and strike a lot of luck.

After the match there was a public talk between frieze editor (and football lover) Harry Thorne, the artists, and a number of the young players featured in the work. One of the girls admitted she kept a piece of the pitch’s grass: a reminder of how meaningful a site can be. A few weeks before Football N, there was a PAM performance at the Olympic Stadium. Massimo Furlan organized the reenactment of a game from the 1974 World Cup, in which East and West Germany faced each other in the last match of the group stage, each having already qualified, in a Cold War standoff that ended one-nil to the East. (West Germany went on to win the cup.) In Furlan’s version, A Reenactment of the 1974 East Germany–West Germany World Cup Match, with original commentaries, there were only two players. The artist played Sepp Maier, the West’s goalkeeper, while actor Franz Beil was Jürgen Sparwasser, who scored the winning goal in that fateful game. Maier and Beil played without a ball but accompanied by the original radio commentaries, following a choreography that took place 44 years earlier. At one point, Beil was injured and taken off on a stretcher and a streaker ran onto the field. The audience had no idea where the performance ended and reality began: so many people told me about it that I became convinced storytelling can make a public of you even if you weren’t present.

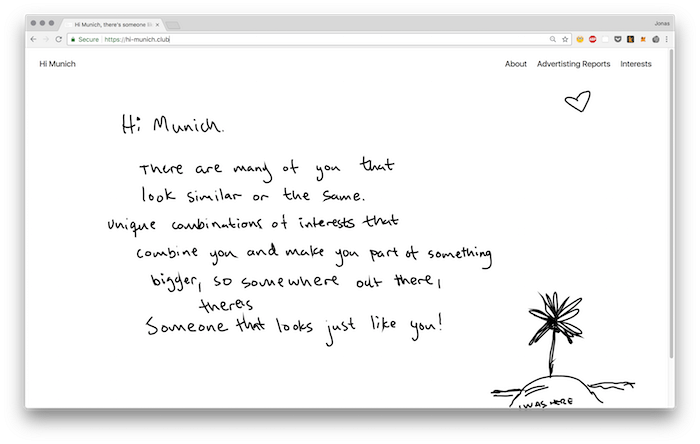

“Hi there, there are 3300 people just like you in Munich, interested in FC Bayern Munich & contemporary art between 13–65 years old,” reads a Facebook ad that is part of Lund’s other project for PAM. Hi Munich is directed at Facebook users in Munich via the platform’s targeted advertising feature. Anyone who would look up the project via its website (https://hi-munich.club/) would also see the advertising reports on how many clickthroughs Lund’s advertisements received after he spent just over €1000 on Facebook ads. These are aimed at audiences divided into such categories as “Contemporary art, Curator, Monthly income higher than 5000 EURO” (only six clicked, from an audience of 18000, of whom 1024 were reached by the ad), or women interested in “Painting, Very Important Person, Contemporary art, Time travel, Vegetarian Cuisine” (648 reached; 20 clickthroughs). To see how Facebook thinks of—and monetizes—users and their interests is to know how you could constitute an audience and recognize some of the stakes thereof. In doing so, Hi Munich highlights PAM’s complex idea of public art— a space where a public recognizes itself as such.

In her book about public art and site specificity, Miwon Kwon discusses how, while some celebrate globalism’s facilitation of a speedy exchange of information and commodities, the end result is a homogenization of places and erasure of cultural differences—“the increasing instances of locational unspecificity.”1 At a time of growing sameness, where museums, biennials, and galleries in different cities all show the same work, PAM puts forth not a claim to uniqueness but to a sense of embeddedness. Kwon prizes site-specific practices as an exploration of the search for a “place-bound identity.” At PAM, the works take the city, its sites, and its history as points of departure, with an eye to specific stories that comment on each site while posing questions about its publics. Artists, audience, and city meet to ask whether coming together, for 90 minutes or 90 days, could change the game, even rewrite the rules.

Miwon Kwon, One Place After Another: Site-Specific Art and Locational Identity (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 21.