“Histórias Brasileiras” [Brazilian Stories] is a profoundly depressing show, a curatorial snapshot of a country, it would seem, at the end of its tether. It coincides with the closing months of Jair Bolsonaro’s grueling first term as the country’s president, opening just before the world’s fourth biggest democracy goes to the polls. The complaints and traumas presented in the exhibition are legion. That does not, however, necessarily make it a great exhibition.

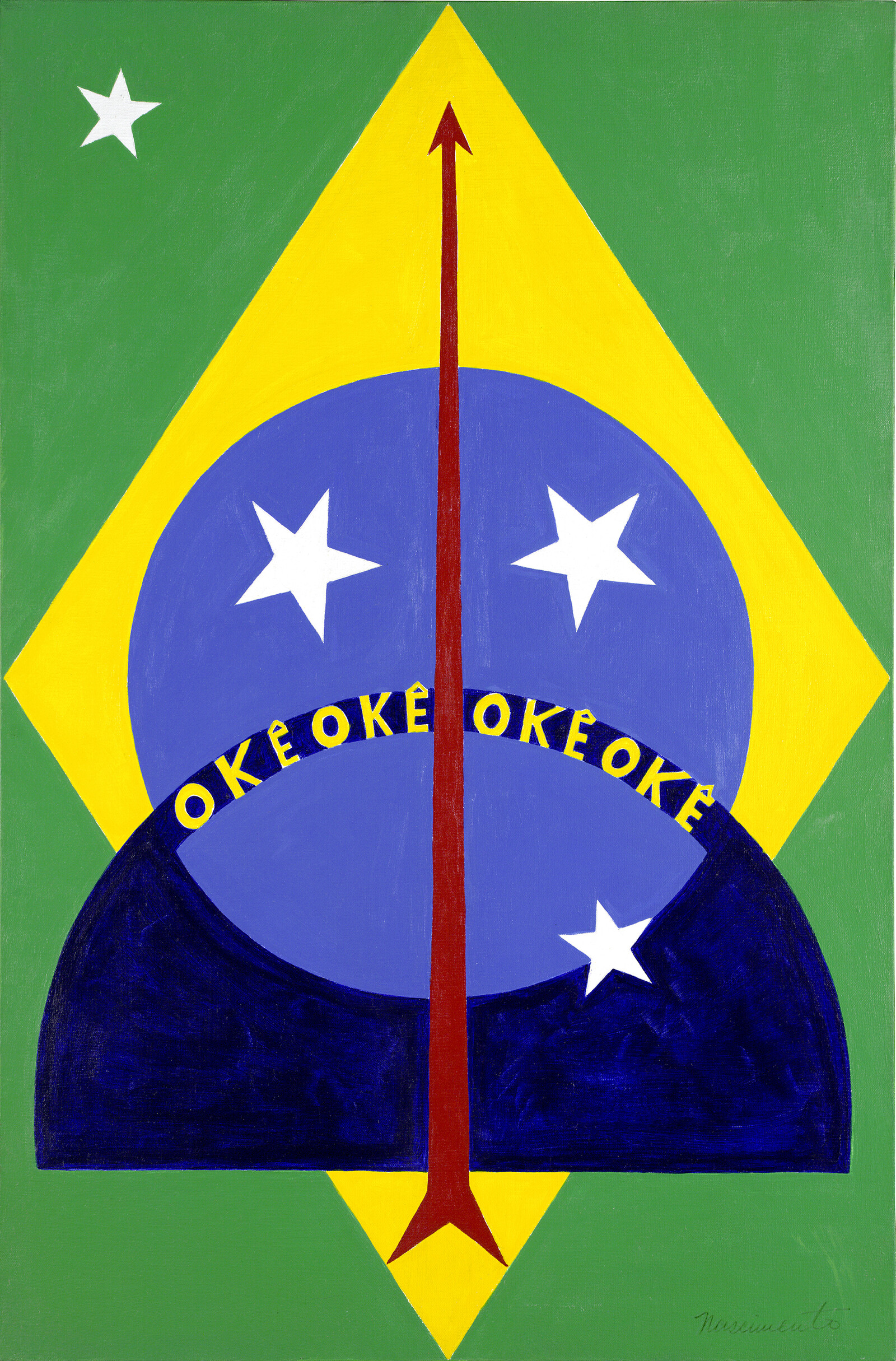

Adherents of Bolsonarismo have long co-opted Brazil’s national flag. And so it is as a presumed rebuke that the curators present a series of reimagined versions of the blue, yellow, and green standard to open this sprawling exhibition (over 400 objects divided between eight thematic chapters, the first of which is titled “Flags”). Abdias Nascimento’s Okê Oxóssi (1970), in which the late artist and activist inserts symbols of Candomblé, the Afro-Brazilian religion, into the composition and palette of the original national design, subverts the European Christianity that has long held power in the country. It hangs alongside Mulambö’s Remembering Thy Noble Presence (2021), a funereal silhouette of the globe and diamond motif made from black plastic rubbish bags; and Leandro Vieira’s Brazilian Flag (2019), a rendition of the insignia in the light blue and pink of the trans liberation symbol. Instead of the original “order and progress,” Vieira’s version declares itself also for the “Indigenous, Blacks and Poor.” Collected together, they lose their individual intensity: a criticism that foretells the repetitiveness of a show that on the one hand has far too much work (much of dubious quality), and on the other feels one-dimensional—despite claiming to tell plural stories.

Further chapter titles, each corresponding with closely hung or shared galleries, include “landscape and the tropics,” “land and territory,” and “the body.” Invariably, the curatorial modus operandi is to use contemporary works to protest colonial narratives divined from the historic art on show (much of which comes from the museum’s collection, which for decades was weighted heavily towards European art). Charles de Clarac’s Virgin Forest of Brazil (ca. 1822), an astonishingly detailed etching and watercolor of the rainforest painted in the tradition of the nineteenth-century sublime, is countered, in the same space, by Jefferson Medeiros’s Current Map (2020), an ammunition shell hammered and melted into the shape of Brazil. In the following room Sepp Baendereck’s On the Transamazon Highway between Maraba and Altamira (1977), which swaps the Edenic paradise of the previous century with an image of a scarred and damaged landscape, makes the point clear. In Baendereck’s vision, uprooted trees with limb-like branches pile up like bodies in a mass grave (illegal mining, done with the tacit approval of the current president, has led to a vast increase in the murder rates of Indigenous land defenders).

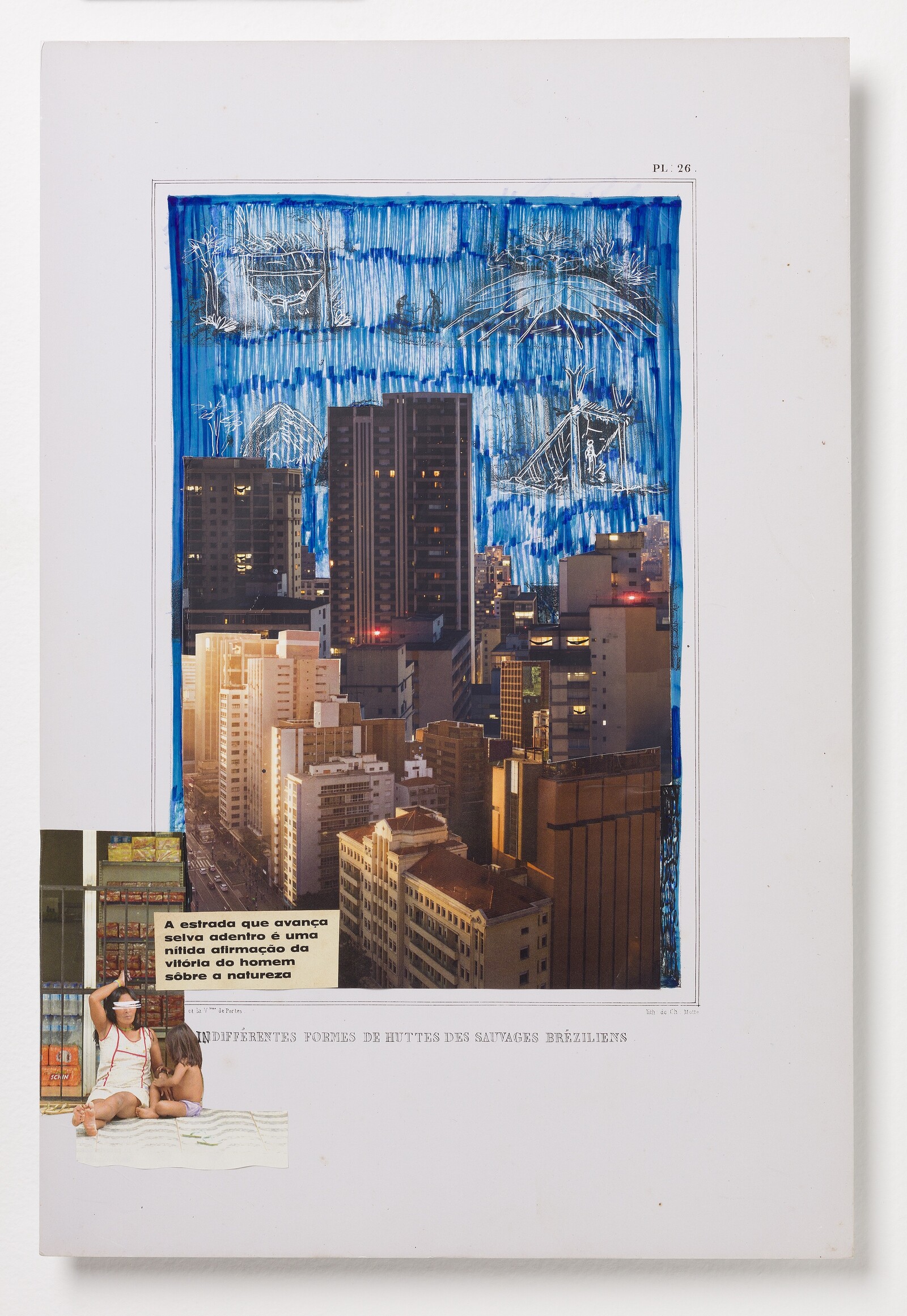

Playing a similar role is Denilson Baniwa’s beguiling Indifferent Forms of the Brazilian Savages’ Housing (2019), in which the artist, who is of the Indigenous Baniwa people, has collaged found photographic imagery of city high-rises onto the felt tip-drawn forest night sky. Amidst the dark blue expanse, different forms of Amerindian shelters hover like ghostly constellations. The works, from successive centuries, are solid in their own right, and combined press the visitor to pass judgement on extractivist industry and rapid urbanization.

That same point, however, is labored by repetition: the curators (of which there are eleven, subgroups taking responsibility for specific chapters) have hung, as one of countless other examples, Victor Meirelles’s so-so landscape Partial View of the City of Nossa Senhora - Present Florianópolis (ca. 1847) below contemporary conceptualist Marcos Chaves’s I only Sell the Sight (1998), a picture postcard view of Rio de Janeiro’s Sugarloaf Mountain with the work’s title, in Portuguese, superimposed in white text on a black bar. Like de Clarac, Meirelles was a favorite of the Portuguese royalty, and that heavy history reduces Chaves’s project to a one-liner on imperialist exploitation. While the artist certainly comments on this, it is also a work with complexity and depth that plays with Pictures Generation questions of image and signage, among other things.

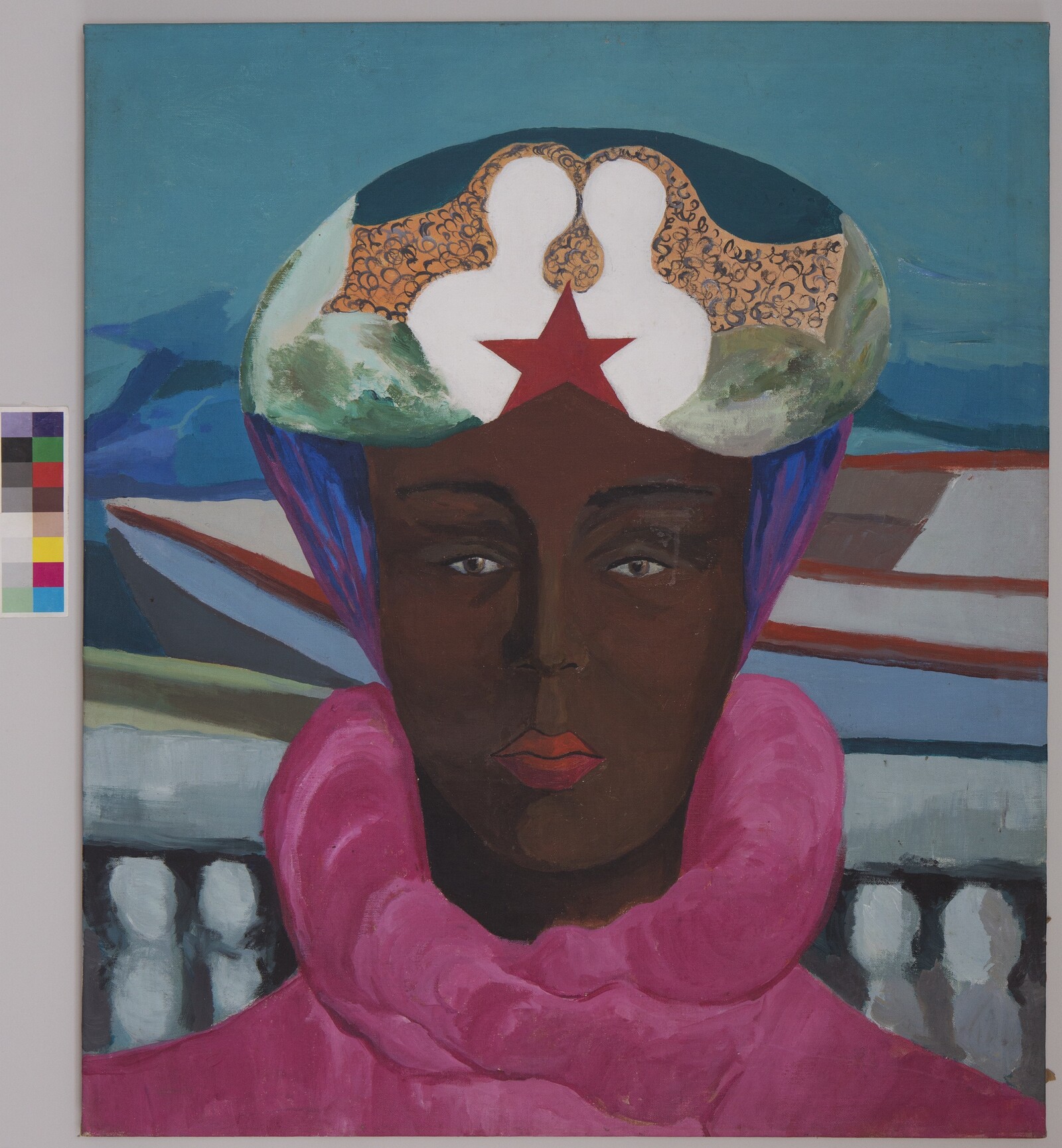

On the lower level of the museum, further thematic chapters play out. None of these provide much surprise, and an exhibition design reminiscent of a series of art fair booths doesn’t help. A long corridor-like gallery of portraits, dating from the 1950s to the present day, seems superfluous to the exhibition’s narrative; while a section on parties feels underdeveloped—though it does provide a couple of gems: in Maria Auxiliadora da Silva’s languorous painted collage, Três Mulheres (1972), two women lie comfortably naked on a bed gossiping in speech bubbles about the night ahead while a third hides behind a curtain.

Curiously, a section on religion and belief provides a rare moment of redemption: old depictions of Christ hang close by glorious contemporary works, rich in color and celebration, by Daiara Tukano, the late Jaider Esbell, and the Movimento dos Artista Huni Kuin, all of whom belong to different Indigenous groups. The patterning in Tukano’s canvases, the spirit-animals painted by Esbell, the ayahuasca ritual depicted by the Huni Kuin artists effectively demonstrate how community is created by the expression of shared beliefs, not individual traumas. Otherwise Pedro Marighella’s small, untitled 2020 acrylic-and-ink drawing, which depicts the concrete and glass architecture of MASP cracked in half, wire and steel innards dangling limply from the building’s truncated limb, feels closer to the curators’ mood. Broken and divided: this does not have to be the only Brazilian story.