In a videotaped recording of a 1980 performance of Jacqueline Humbert and David Rosenboom’s song cycle Daytime Viewing, a woman wanders across a dim stage. She wears a bright green printed housedress—the shapeless body-concealing kind—and large fluffy slippers; she nervously settles into her spotlit destination, a chair set in profile close to a TV set. Her reflection is briefly visible on the blank screen as she fiddles with a knob to turn the set on, then, screen illuminated, she pulls up a channel displaying a nested image of another woman in profile watching TV. The tableau is soundtracked by uneasy synthesizer melody, and a voice narrating: “She was all she had, and it was more than enough for now. She was a survivor, addressing the struggle without by living within. She gathered momentum by living within, contained by a fascination with the view: this trance, this private daytime viewing where any world awaited her arrival.”

Both Humbert and Rosenboom are part of a cohort of musical avant-gardists who play with song as a form that can, often in just a few short minutes, bridge the popular inner core and absolute outer limits of American aesthetics and consciousness. Humbert designed costumes for the late Robert Ashley’s television-opera Perfect Lives (1983) and was later a longtime member of his vocal ensemble; Rosenboom is a computer music pioneer whose work has engaged the human brain and nervous system. Between 1975 and 1979, the pair were members of the Maple Sugar Group, a Toronto-based performance collective whose members included George Manupelli, Mary Moulton, James Tenney, and Ann Holloway, among others. During this time, Humbert performed as J. Jasmine, a songstress whose tunes theatricalized social commentary (on sexuality, sex work, and other subjects). Those intense, character-driven songs presage the more ambitious conceptual musical performance of Daytime Viewing.

Daytime Viewing is best known now through a 1983 audio recording, initially released as a private cassette edition and reissued publicly by the record label Unseen Worlds in 2013. This spring, to mark the fortieth anniversary of the 1983 release, Unseen Worlds offered a 2x-LP expanded reissue. Alongside it, the label’s head, Tommy McCutchon, digitized and uploaded performance footage and visuals that fill in the work’s longer intermedial history. These findings emphasize the degree to which visuality and theatricality are essential to Daytime Viewing’s operation, and flesh out its stance on the objects it investigates. Viewed as a performance, Humbert and Rosenboom’s concept of what a song might encompass swells to become a mode of live audiovisual storytelling that harnesses the hallucinatory capabilities of its subjects, among them soap operas and haute couture. Whether the warm glow of a television screen or the flash of sequins caught in a spotlight, Daytime Viewing took the surfaces used by consumer culture to stimulate and reflect women’s desires, arranging them in a charming way to tell a story about the stories mass culture encourages us to tell ourselves.

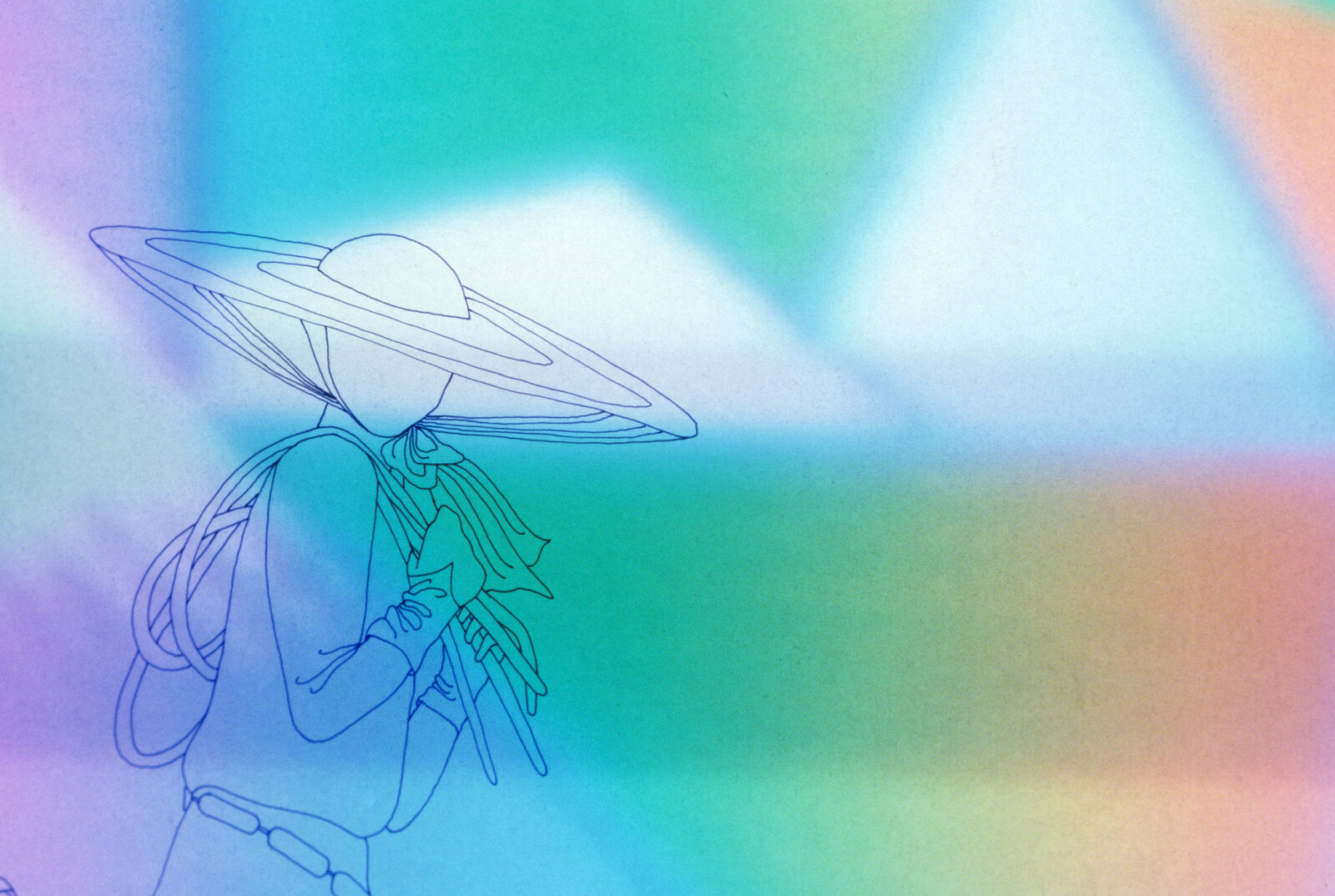

To do so, Daytime Viewing’s theatrical structure interlocks song and costume, both of which arrive haunted by the television screen. In intermittent fashion-show sequences, Humbert invites us to “escape through the world of Avant Garter,” Humbert’s own atelier, outfits by which are trotted out to an upbeat marimba-and-cowbell shuffle. The ensembles are visually titillating, but also contain narrative threads, so to speak, emphasized by their descriptions, which are read by Eugenio Tellez. Among the eye-catching but darkly absurd garments crafted by Humbert: a hot-pink miniskirt-suit topped off with a metallic conical hat (“Schizophrenia, neurotic behaviors, severe paranoia: whatever the diagnosis, merely ignore it in this delightful ensemble of fuschia silk, with genuine gold thread border detail”); a shimmering violet pencil skirt and fitted peplum top with a matching wide-brimmed hat (“What man could think of beating his wife black and blue when he sees his wife like this? Put an end to constant quarreling and take no abuse in this timelessly stylish ensemble built of brilliant orchid lurex by Jacqueline for Avant Garter Fashions”); an ivory satin dress adorned with a layer of mosquito netting, delicately bunched and ruffled around the hip, worn with snakeskin heels and a netted visor-veil (“an enticement to your every desire, and yet repellent to the unwanted pests in your life”). From elsewhere, Humbert sings “Wishes,” a lilting ode to daydreams invented from beneath a duvet on the couch: the desire to go to Paris or Los Angeles, imagined places that frame half-sketches of other lives.

When Humbert takes the spotlight between catwalk sequences, she performs the work’s most conventionally structured—and most lyrically disquieting—songs, each of which narrates a relationship falling apart. She’s a campy presence, but also the voice of a cruel reality, delivering tales of disinterest, familial negligence and child abuse, and violent partners with hammy intensity, played up by Rosenboom’s feverish piano accompaniment. During “Domestic Violence,” Humbert cradles a handgun, clutching it to her heart while lamenting how, in face of a partner’s abuse, “lonesome takes me in embrace another time.” Her slinky slipdress is cut from the same fabric as the housedress worn by the TV-watcher depicted elsewhere.

Escape from these scenarios is, for Humbert and Rosenboom’s characters, mediated through television. The couch-and-TV tableau is accompanied by a shift to a disquieting minor key. This section’s instrumental is a musical highlight, played here by Rosenboom on the Buchla 300 Series Electric Music Box. In these sections, Sam Ashley narrates the “descent into dreamtime” of a woman who, alone and likely suffering from some combination of the violences endured by Humbert’s models and musical subjects, remodels her life on the plane of daytime soap operas. (The recorded version uses Humbert’s breathy voiceover and an instrument called a Touché, an even more distinctive-sounding computer-assisted keyboard designed by Buchla and Rosenboom that produces a landscape of future-carnival squelches; it replaces the mournful ambiance of the performance with an eccentric bubbliness.) The soap and its ideological narratives of romance, family life, and heroic self-invention—not to mention its interestingly costumed and well-groomed leading ladies—become a means through which an otherwise disempowered woman might develop an extensive fantasy life. That fantasy offers pleasure and solace—“it kept her alive,” per the monologue—but in this tableau, which offers a view outside “the view,” we are shown a woman stilled and contained to the point of virtual lifelessness.

Daytime Viewing’s combination of spoken-word narrative voiceover and avant-garde instrumental is reminiscent of a maudlin, stripped-down version of Perfect Lives, which at this time would have been circulating as a performance. Like Ashley, whose work was in fact meant to be shown on television, Humbert and Rosenboom seem to draw some connection between the potential for emotional immersion in both song and screen. But whereas Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives takes the dyad or couple form as a source of relational structure, Daytime Viewing is in a sense about the aftermath of the couple breaking apart, and television’s near-mystical ability to fill, if not exactly heal, the void of a broken heart.

Indeed, Daytime Viewing came into being around the same time as many artworks about, or making use of, television. The work, as far as I can tell, has evaded art historical attention; this could be due to its development outside of the very fantasy-cities it names, or perhaps because of the theatrical excess it not only entertains but cultivates, spinning its meditation on TV across narrative, song, choreography, and costume. Humbert and Rosenboom’s aesthetic mode is based in the flight of fancy, but the work’s depth comes from their ability to find form in fantasy and the desires that propel it, not to mention how seriously they take fantastical narratives generated in response to the pain of the everyday. As the narrator tells us in the “Talk” voiceover, “The wanting was real, and she kept it alive.” The woman wanting on the couch participates in a sublime process of invention that’s focused and creative, if entirely sedentary, a technologically (and sartorially) augmented version of the human impulse to, as it were, tell oneself stories in order to live.

Four decades later, in our audiovisually saturated present, it’s something of a cultural cliché to entertain worldbuilding as a response to various crises of the past and present: I am thinking here of the promise often made by curators and press that various artworks “imagine other worlds,” to presumably utopian social effect. Daytime Viewing examined a version of that impulse as it was, and remains, occasioned and capitalized upon by commercial media. It did so without lingering in the sentimental promise of repair, and with an at times startling frankness towards the conditions that occasion our need to escape. But Humbert, Rosenboom, and their collaborators built their own uneven world all the same, presenting song as an avant-garde and interdisciplinary mode through which to simultaneously tell stories and reflect upon how narrative operates within contemporary life.