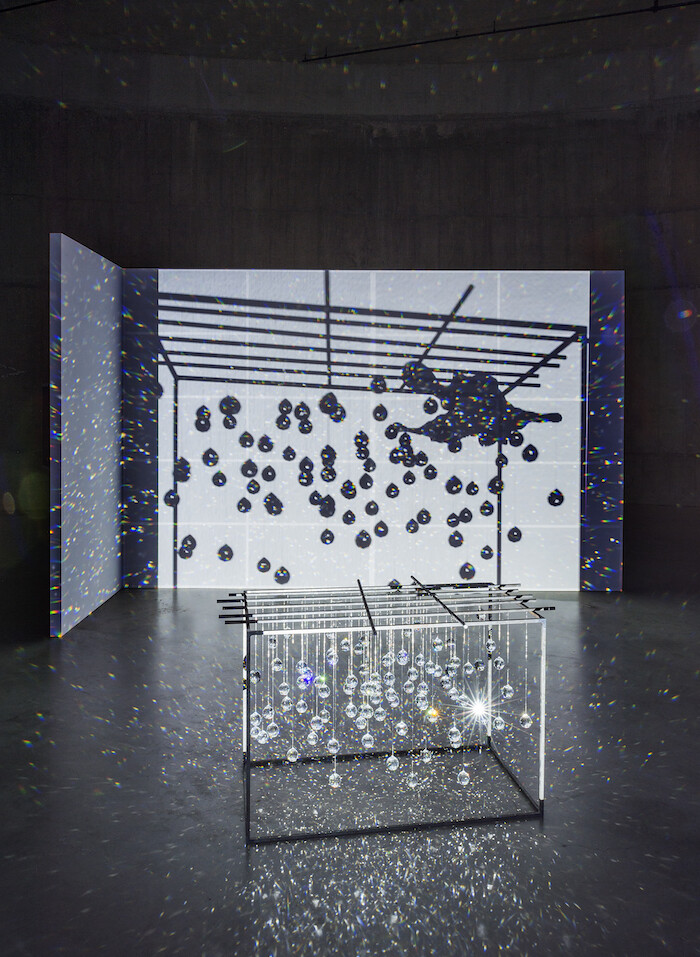

When I was a child, I received a disco ball as a birthday gift. Hung haphazardly above my bed and lit by a repurposed old desk lamp, it reflected a scintillating constellation across the ceiling. In a flick of a switch, the quotidian transformed: I had entered a secret world. A kind of Proustian magic occurs when an artwork triggers not only an involuntary memory but an ineffable bodily feeling. Walking into Joan Jonas’s installations—Reanimation (2010/2012/2013) and Wind (1968)—in the East Tanks of Tate Modern did precisely that. The cavernous space had become an enigmatic new universe: the rough walls animated by shimmering video projections, with crystal spheres refracting flickering light, and the howling noise of gale-force wind intertwining with strange percussive sounds.

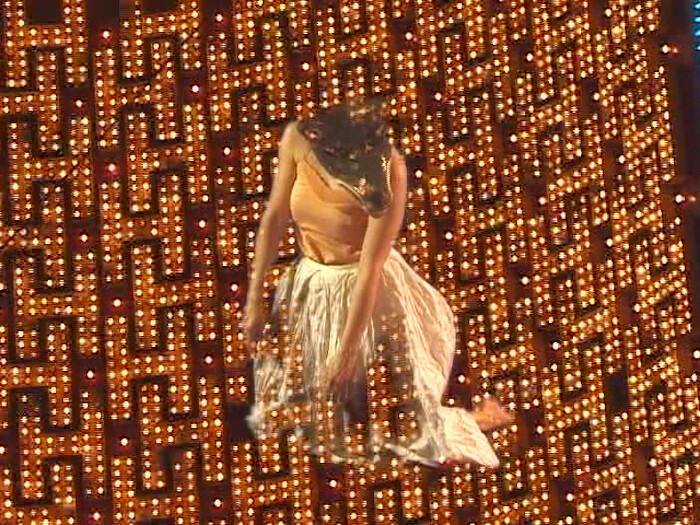

Jonas’s oeuvre eludes genre. Throughout her career, she has blended technology—video screens, re-recorded backdrops, overheard projectors—into historical systems of communication, engaging with traditions of shadow puppetry, mythology, ritualistic music, and Noh theatre. Her work travels from factory lofts to wasteland docks, across landscapes and seascapes, deserts, cities, and hilltops. Jonas’s show at Tate Modern eschews a chronological retrospective in favor of a nonlinear survey paired with live performance and cinema programs. In alignment with Aby Warburg’s logic of intuitive juxtaposition in his Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–29)—one of Jonas’s manifold references—the exhibition’s format reflects the artist’s non-didactic approach, allowing for a multiplicity of encounters and interpretations. In response to the numerous focal points in her work—starting with Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy (1972), where a camera transmitted a video feed of the artist’s performance to the audience while it unfolded live—Jonas commented: “The work reflects the mind. We are able to follow several thoughts or images simultaneously.”1 The Tate Modern show operates in a similar manner, with the hubbub of various soundtracks overlapping and blending together, chorus-like, in the space.

Jonas is fascinated by looking. Her work abounds with mirrors, layered images, shadows, curved wooden screens, fish-eye lenses, and special effects that distort, alter, and reconfigure space. Her early choreographed works Mirror Piece II (1969/2018), Mirror Check (1970/2018), and Mirage (1976/2018)—restaged as part of “Tate Live: Six Nights” in March—employ mirrors as props, and explore how distance, suspense, narcissism, and intimacy can be instigated in the spectator. In doing so, she reveals the plasticity of performance and spectatorship: their potential for play, chance, and improvisation.

Appropriately for an artist who draws on shamanic and mystical traditions, Jonas revisits the past throughout her practice, adapting earlier works and using objects from time-based performances to create static, staged environments. The Juniper Tree (1976, reconstructed 1994), her reaction to the Brothers Grimm fairy tale of the same name, evolved considerably between 1976 and 1978. It currently exists as an expanded installation, including 78 slides from the original performances alongside an audio soundtrack. Jonas’s interest in re-staging carries through to the portable, miniature theaters dotted throughout the exhibition: square wooden tubes resembling giant telescopes, with large viewfinders that spectators can peer into. Some, such as My New Theater V: Moving in Place (Dog Dance) (2002–05) screen video works in intimate contexts; others, such as My New Theater I: Tap Dancing (1997), with their tiny, dollhouse props, contain precise dioramas resembling miniature recreations of the stage sets in which Jonas performs. Such works collapse sculpture, architecture, and video into artistic microcosms that expand rather than narrow viewers’ horizons. The masks, wooden animals, and props that appear across numerous works, meanwhile, function like a visual alphabet. Jonas gathers imagery from myths and fairy tales in a similarly playful way: as material to be combined and re-configured into poetic arrangements.

The role of women—as orators, outsiders, and oracles—is central to Jonas’s relationship with folklore and verse. Volcano Saga (1985–89) responds the thirteenth-century Icelandic epic The Laxdaela Saga, which some scholars have attributed to an unknown woman author due to its detailed portrayal of female experience. Helen of Egypt: Lines in the Sand (2004), made during the US invasion of Iraq, is based on poet Hilda Doolittle’s book Helen in Egypt (1961), a feminist reworking of classical Greek drama which contends that Helen was never in Troy and the Trojan War was therefore fought on false pretenses. Jonas transposes her version of the story to Las Vegas, the ultimate city of illusions, showing footage of the mock-Egyptian Luxor Hotel and Casino alongside photographs from her grandmother’s trip to Egypt in 1910.

Jonas’s recent ecological concerns surrounding animal extinction and climate change inform Stream or River, Flight or Pattern (2016–17), which fills an entire room. Large drawings of birds are hung on walls covered with thick washes of dark orange paint, while videos projected onto three large screens show footage of communities in Venice, Singapore, Nova Scotia, and Vietnam interacting with their natural environments. Jonas’s interest in cyclicality—as ritual, history, politics—reinforces her understanding of human consciousness in the context of broader ecosystems. This interest is most present in her new performance, staged in the Turbine Hall, Moving Off the Land. Oceans—Sketches and Notes (2018), a tribute to the miraculous and fragile world of the ocean that evidences the artist’s fascination with the social relationships between the ocean’s creatures. In one sequence, Jonas draws on Sy Montgomery’s book The Soul of an Octopus (2016), to espouse the animal’s wild spirit and deep intellect. It reflects Jonas’s work itself: its generosity, sense of feeling, and the myriad connotations extending toward the viewer like elongated tentacles.

Joan Jonas quoted in the Tate Modern exhibition guide, 2018.