In 1939, the German artist Hans Tombrock (1895–1966) inscribed the words of his contemporary Bertolt Brecht’s 1935 poem “Questions From a Worker Who Reads” onto a wooden board. Both in exile from the Nazis, Brecht and Tombrock met in Stockholm earlier in 1939. They collaborated on several works and developed a longstanding dialogue on art in the workers’ movement, a set of riots and strikes at the turn of the twentieth century, and the institutionalization of the Swedish Trade Union Confederation, the Swedish Social Democratic Party (SAP), and social security. This spring, Tombrock’s piece, which borrows its title from Brecht’s poem, was exhibited in the group show “Den folkliga självstyrelsens livsluft” [The air which the autonomy of the people breathe] in Stockholm, alongside contemporary artworks that explore labor, exhaustion, and leisure. It was the first exhibition at Mint, a new non-profit art space in Stockholm founded and run by curators Emily Fahlén and Asrin Haidari. Last year, together with artist Thomas Hämén, Fahlén and Haidari curated the 2018 edition of the Luleå Biennial in northern Sweden. Titled “Tidal Ground,” the biennial critically investigated the local and global extraction of natural resources and workforces, alongside the role of art in antifascist mobilization. At Mint, the two curators examine art’s historical and current role at a time when workers’ rights are under threat in Sweden and beyond.

“Den folkliga” drew on the work of Swedish art historian Gregor Paulsson (1889–1977), who in 1936 initiated “Fritidsutställningen” [the Leisure Exhibition] in Ystad, an outdoor show aimed at highlighting the vital role that leisure plays in people’s liberation. Eighty-three years later, Fahlén and Haidari underscored the historic value of leisure for autonomous study, organization, and cultural production. They argue that the notion of “workers’ art” needs to be reexamined. “With an increasing number of precarious workers across the political spectrum,” says Fahlén, speaking on behalf of the duo, “we need to focus on how these changes are processed by contemporary art, and to read them on a global level.” Fahlén and Haidari argue that the relationships between political movements, artistic practices, and art history need to be reconfigured. “Art has a history that other areas are lacking. Intersected between fields and generations, this potential can be put to work again—at a time when it is needed more than ever.”

Central to the Swedish version of this dilemma is “folkbildning,” the autonomous education of the people. Throughout the last century, during which the SAP dominated Sweden’s government, Swedish people were encouraged to educate themselves during their leisure time. More recently, the outsourcing of public institutions to private companies has put strain on the education system, public libraries, and cultural institutions alike. Mint is located in the basement of the headquarters of Arbetarnas Bildningsförbund (ABF), the National Workers’ Educational Association. From the 1960s until 1989, ABF hosted the Svea Gallery, which exhibited workers’ art—including Tombrock’s. Occupying the same space in the twenty-first century, Fahlén and Haidari believe that art can build alliances across fields, desires, and establish relations between culture and workers’ rights.

Fahlén and Haidari’s decision to move art back into the ABF headquarters originated in their desire to exhibit Giorgi Gago Gagoshidze’s 2018 essay film The Invisible Hand of My Father. In it, Gagoshidze examines European migratory labor through the symbol of a hand, as central to socialist history as it is to modern liberalism and which, following Adam Smith, he relates to the “invisible hand” of the free market. In 2008, that hand lost its grip. In August that same year, shortly prior to the global financial crisis, Gagoshidze’s father lost his right hand in a workplace accident.

At Mint, Gagoshidze’s piece was installed in front of Ruben Nilson’s monumental painting Arbetarrörelsens historia [The history of the workers’ movement], painted in the 1940s, which depicts masses of striking workers, laboring miners, and woodsmen in Sweden. The pairing attests to Fahlén and Haidari’s desire to forge narratives across historical periods and global contexts. Recurring topics in these forgings include the material circumstances of workers and indigenous people worldwide, and a seeming political and historical detachment among some younger people. “We want to encourage a new generation to reactivate this house and share its resources with older generations, reciprocally learning from these encounters,” Fahlén says. “Alongside its existing infrastructure for study, the ABF headquarters is one of the few spaces in Stockholm that is open for anyone to simply hang out.”

By situating Mint in this context, Fahlén and Haidari argue that art should play a role in the public sphere, embracing a flexible programing model capable of hosting upcoming actions catalyzed by rapid changes in society. “Similarly to the Luleå Biennale, we want to act onsite, catalyzing situations and letting relations grow from within,” says Fahlén. As a result, the program for the fall is still in the making. The open-ended format could be read as a performative action—one that will ensure the space’s longevity, despite funding restrictions and the current agreement, which is set to end next year.

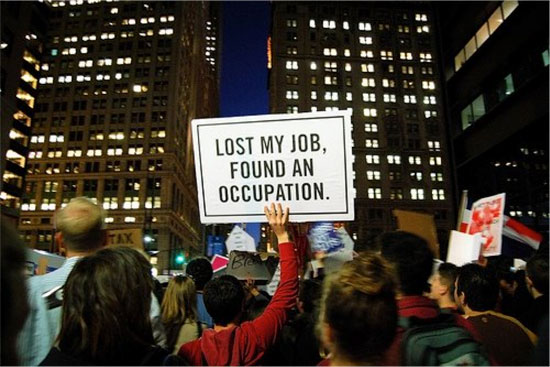

“We want to be honest with what we do: acting in dark times, as long as we can,” Fahlén sustains. “While we don’t have time for identitarian divisions, we hope that this space can be used for various needs, depending on experiences and situations.” After the opening of “Den folkliga,” Mint invited artist Benj Gerdes to present an ongoing documentary project that follows the current “Strike Back” movement in Sweden, defending the right to strike. In 2018, the SAP proposed legal restrictions to the right to strike, which immediately overturned their historical relation to the workers’ movement. The game-changer was instigated by a longstanding industrial dispute and a long-running strike at the Port of Gothenburg, which is now over. The Swedish parliament will vote on the law in mid-June.

A reading group focusing on the legacy of workers’ art is at the core of Mint’s ongoing program. Fahlén and Haidari will continue to investigate this dispersed and overlooked history, and invite practitioners to develop their projects in the space. “Our collective ethos is not just a concept but an essential part of sharing ground to build new, common infrastructures together with others,” argues Fahlén. They have plans to tour the current exhibition to other regions in Sweden, the same way that workers’ art was once spread throughout the country. Alongside new exhibitions in Stockholm, they also intend to establish a residency onsite, in collaboration with Arbetarrörelsens arkiv, The Swedish Workers’ Movement’s Archives. Fahlén admits that their approach is slightly utopic. Yet she argues that art has the potential to develop aesthetic allegiances and offer non-linear readings of art history and the workers’ movement, enabling the intersection of multiple histories in the present moment. In doing so, she and Haidari offer an alternative mode of cultural production that can enter an art context and unfold as a site for study, somewhere between leisure and work.