June 5–August 10, 2019

Pio Abad’s solo exhibition begins, paradoxically, with a work by another artist: The Bridge (To Sonny Rollins), a hard-edge painting from 1981 by Leo Valledor. This prologue to the main act serves a number of purposes. It connects the show to its site through a local artist (Valledor spent much of his life in San Francisco). It reminds us of the impossibility of divorcing art from politics: while the painting is a formal, abstract work with no apparent agenda, the accompanying text posits that Valledor’s lack of wide recognition as compared to his (white) peers was most likely related to his race (like Abad, he was of Filipino heritage). It also introduces Abad’s technique of deploying individual stories to deliberate on historical moments.

Over the past seven years, Abad’s work has engaged, both directly and obliquely, with the cultural legacy of the kleptocrat Ferdinand Marcos, who ruled the Philippines with an iron fist from 1965 to 1986. Themes of mythmaking, collective memory, and amnesia are explored in this exhibition without dogma. Instead, Abad expresses the absurd cruelties of authoritarianism through quietly persuasive, poetic works. He plucks objects from history and expands their meanings through shifts in form and context. Site is significant, and material operates as metaphor.

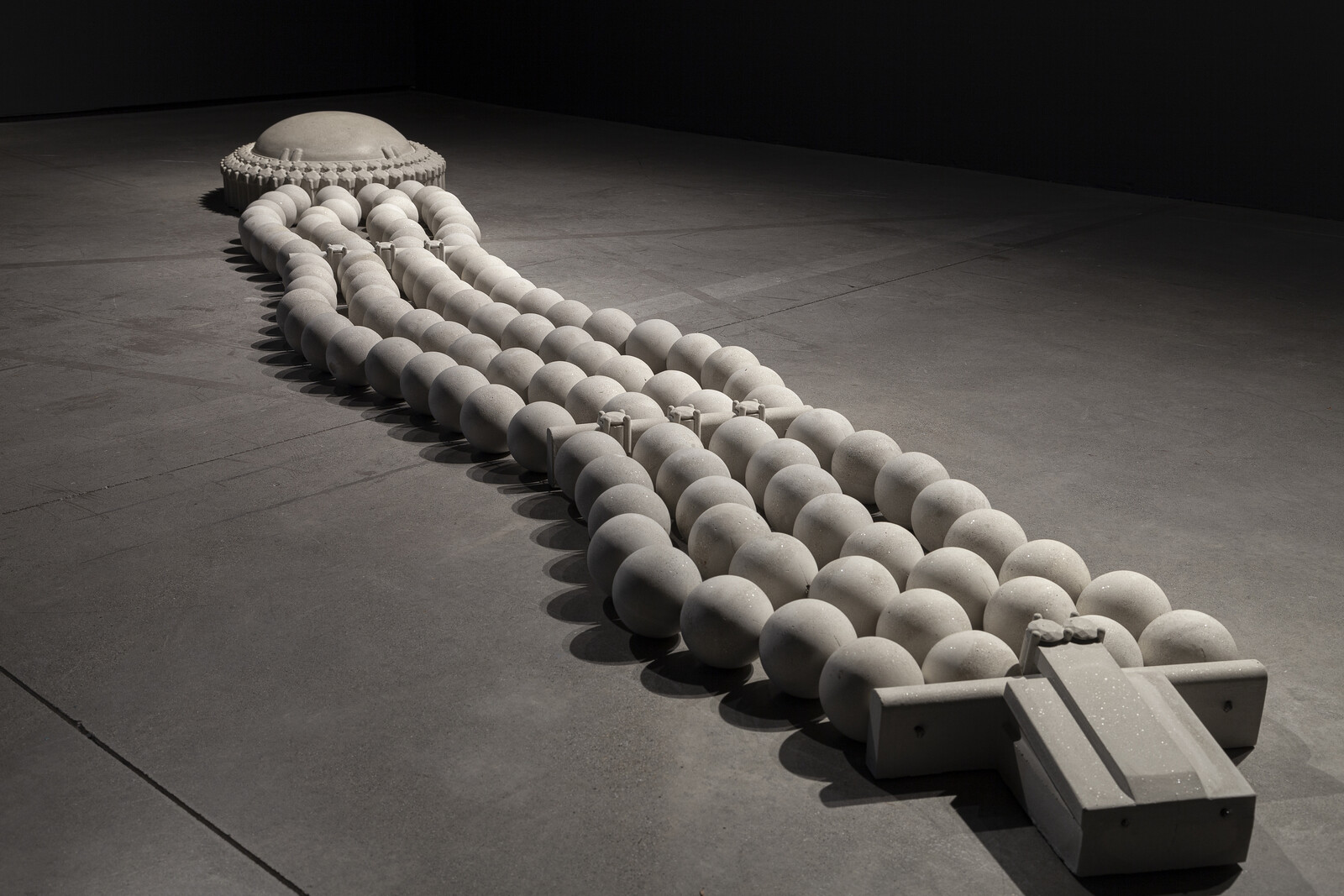

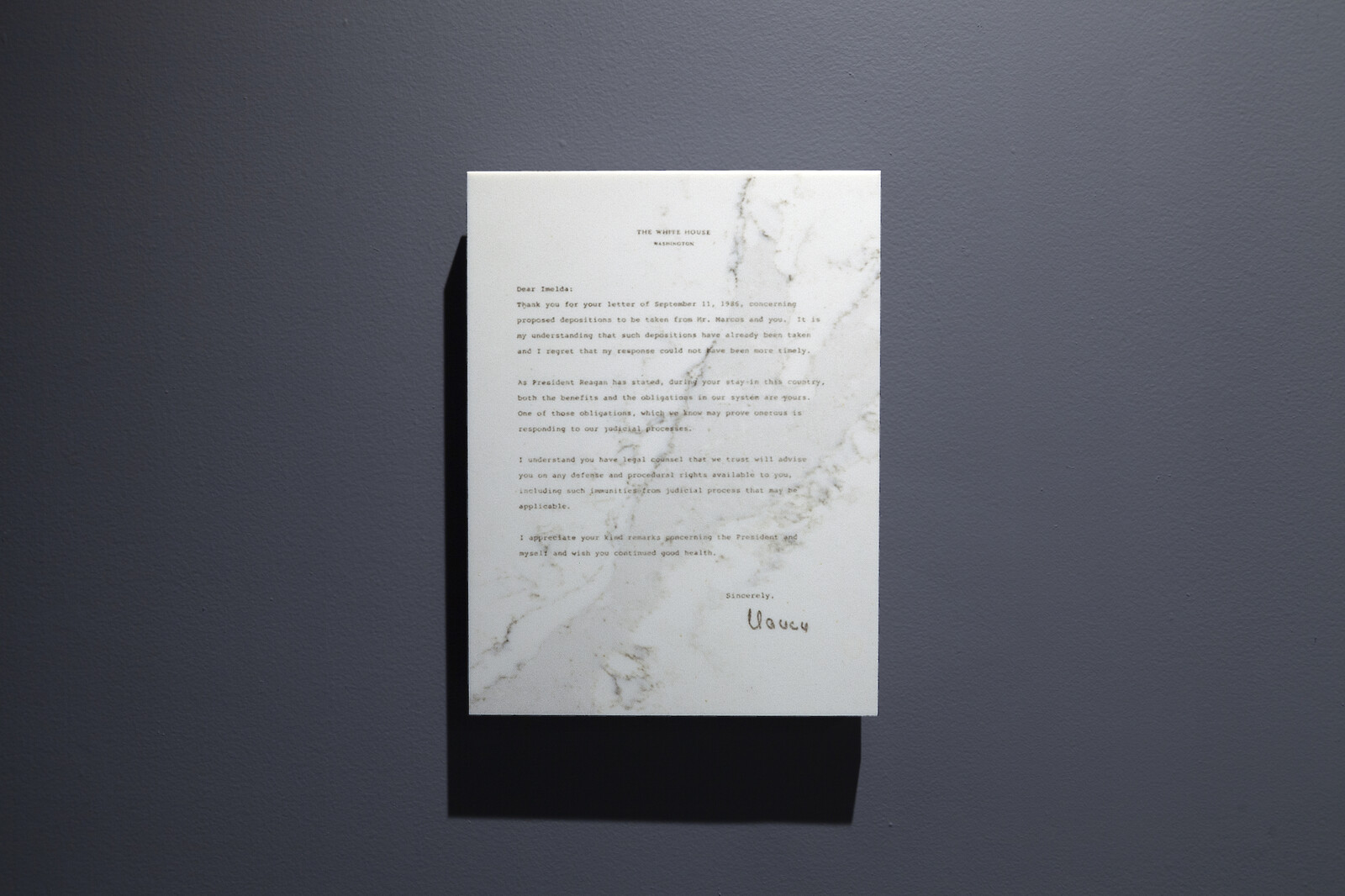

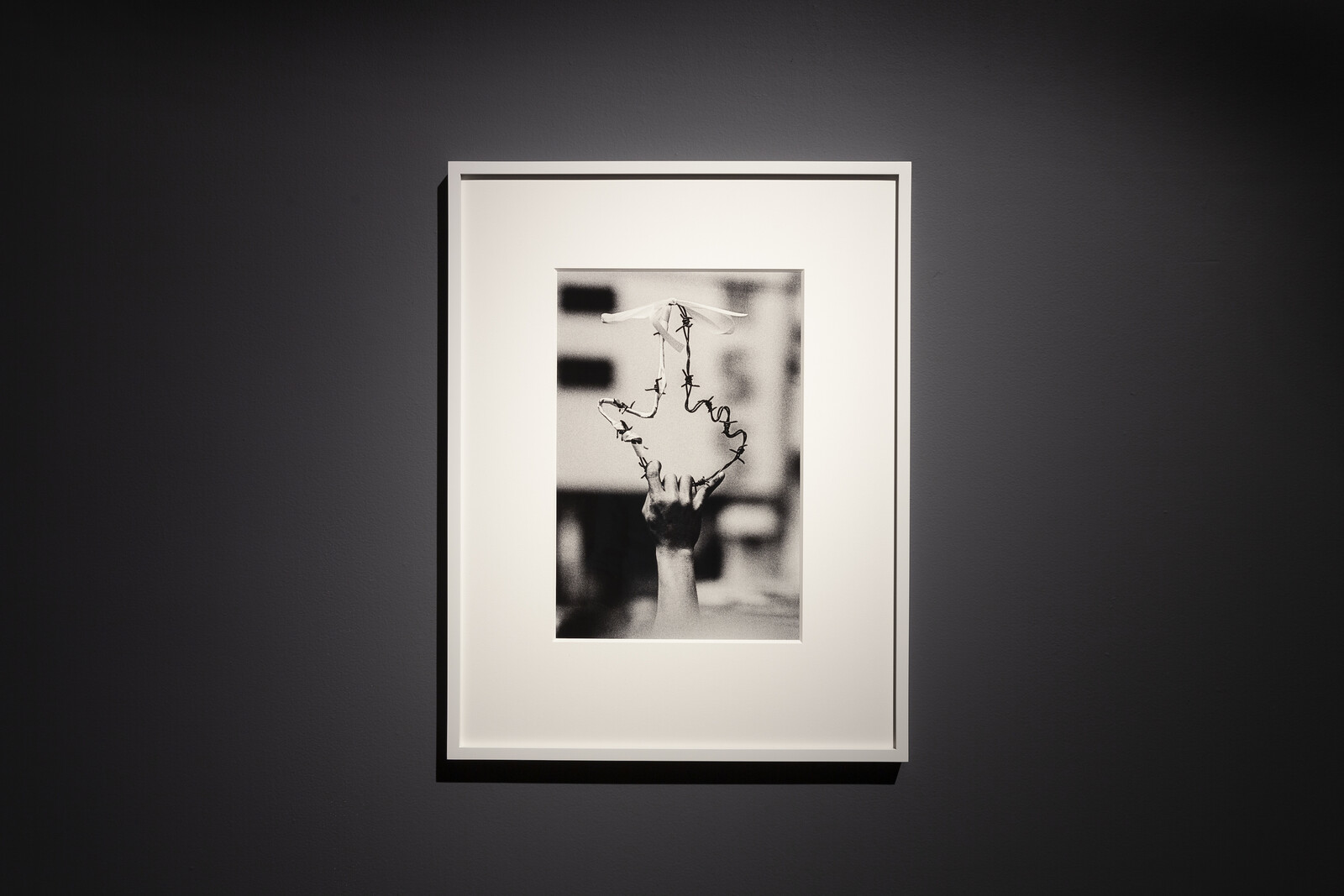

In the main gallery, Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite (all Abad’s works in the show are from 2019), an oversized concrete bracelet—four pale gray strands of beads the size of grapefruits bookended by jewels and a fastener—rests heavily in the middle of the floor. The sculpture is modeled after a photograph of former First Lady of the Philippines Imelda Marcos’s jewelry, which was seized in Honolulu when the Marcoses fled there in 1986. Abad has removed the glamour and glitz from the original ostentatious gold, ruby, and diamond piece, instead linking it to defeat and melancholy through this drab, supersized version. Splayed across the floor like a dead body, the sculpture is resolutely solid in an otherwise slippery world. On the wall hangs a black-and-white photograph taken by San Francisco–based photojournalist Kim Komenich at a protest in Manila on February 24, 1986, the day that Marcos fell. A raised hand holds barbed wire formed into a revolutionary symbol of a hand with its index finger pointed upward, countering the implied hand that once flaunted the gaudy bracelet on the floor. While the Marcoses were escaping, activists were celebrating the end of terror. Also in this gallery is A Thoughtful Gift, a slab of Carrera marble engraved with a letter from Nancy Reagan to Imelda. Writing a few months after the Marcoses’ exile to Hawaii, Reagan slyly counsels her friend on judicial immunities available to her in the United States. By etching these words in stone, Abad renders her unscrupulous advice incontrovertible.

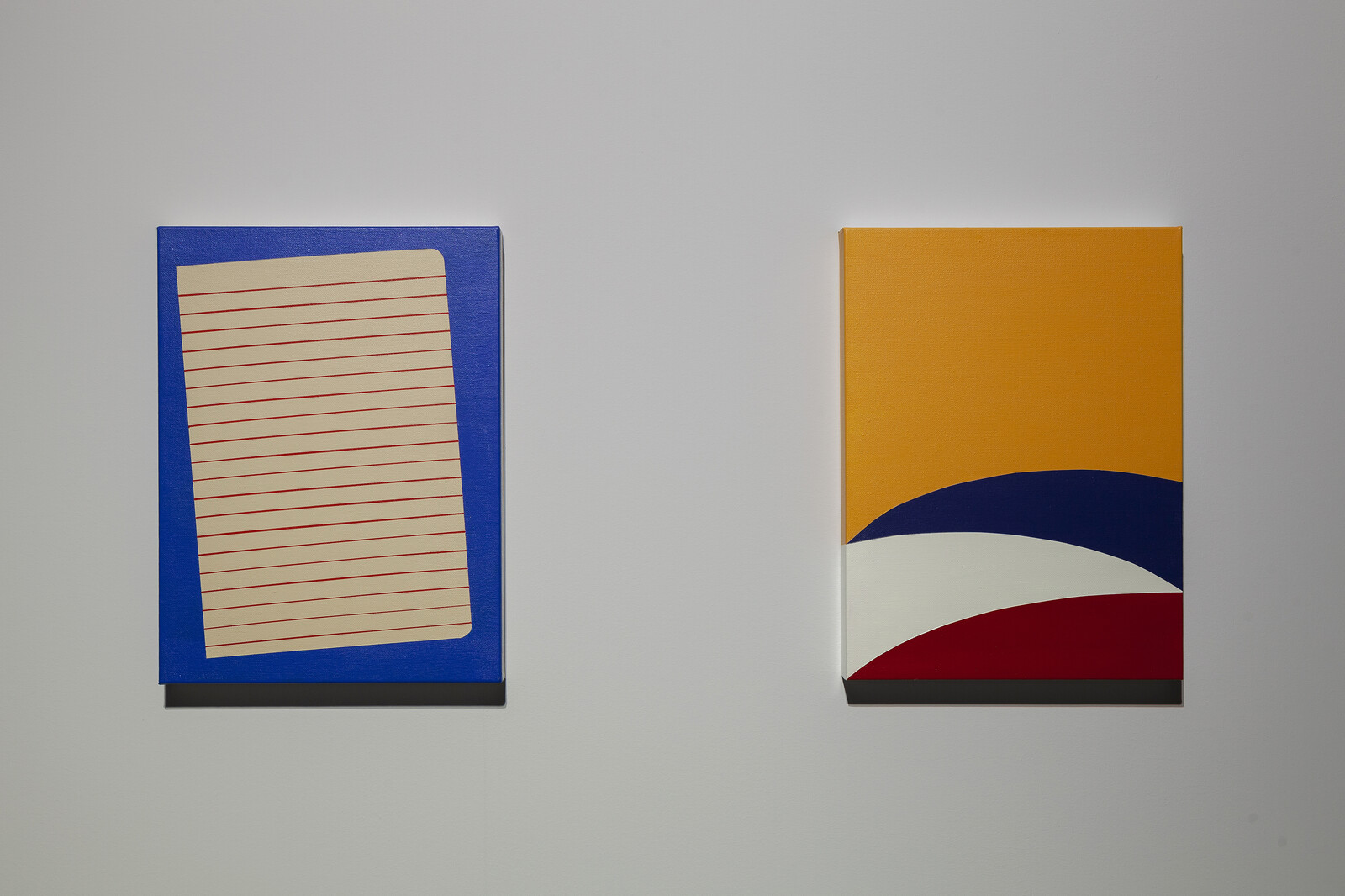

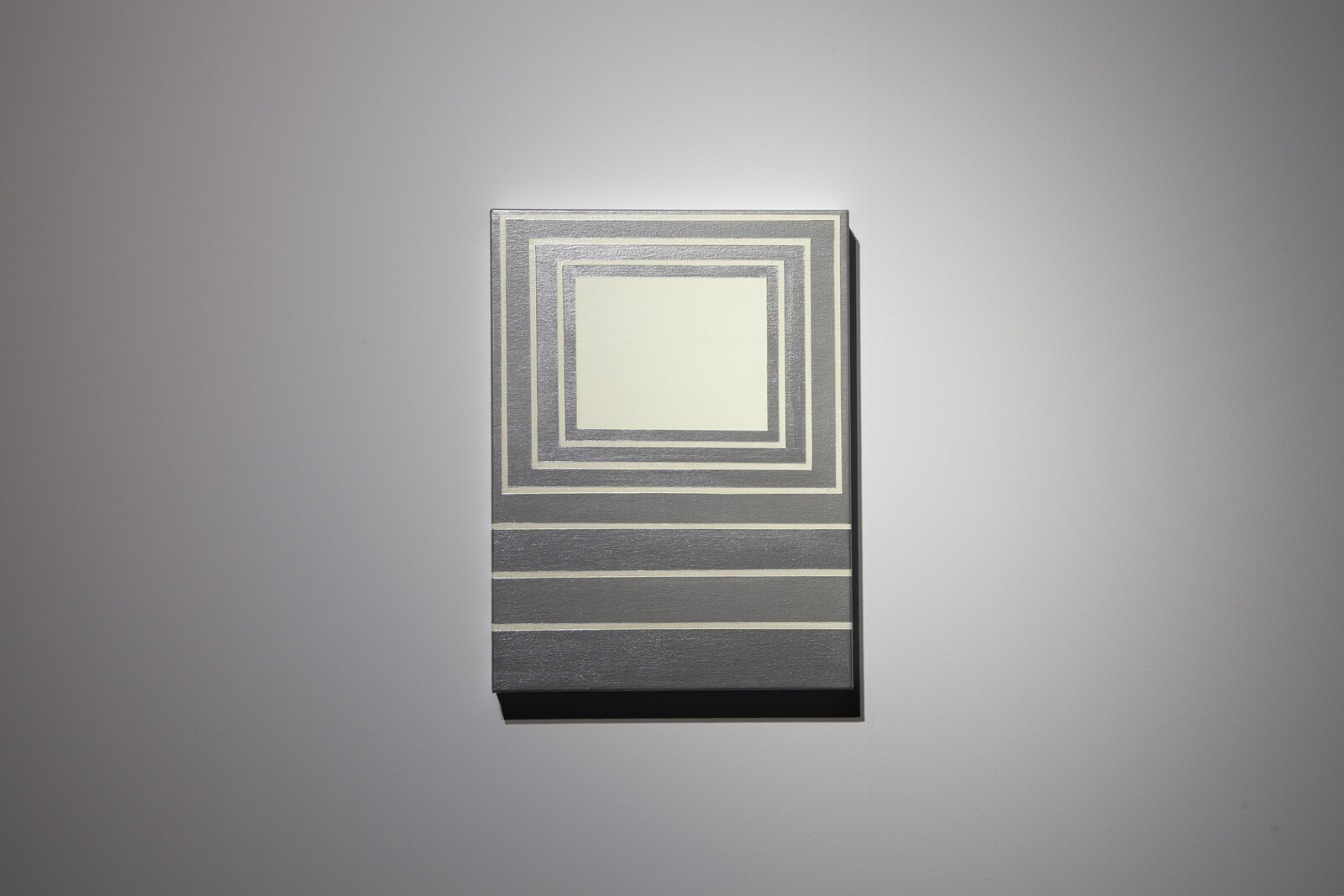

Three small paintings in the third room, For Gene, For Silme, and For Dina, appear to be simple geometric abstractions, connecting them back to Valledor’s painting. But, like the other works in the show, they are multifaceted: their design is based on book covers from Marcos’s published manifestos with the text removed, emphasizing the perennial links between art, design, and politics. The first two works are dedicated to two young leaders of the Union of Democratic Filipinos, who were assassinated in Seattle in 1981, while the third is named in memory of the artist’s mother, a political activist. The artist’s rejection of the words on the page effectively makes the propaganda impotent, converting the designs into memorials.

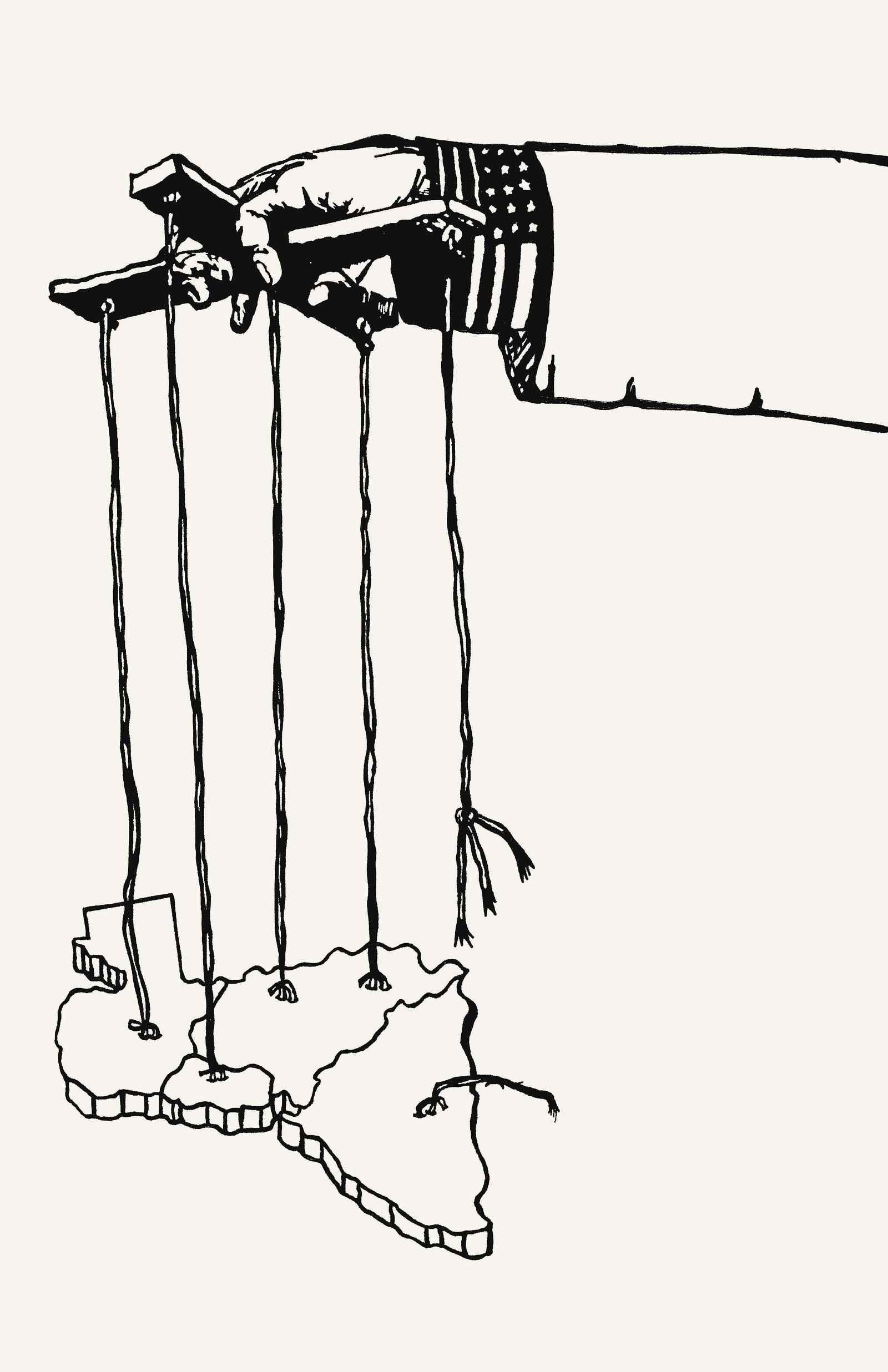

From outside the gallery, Untitled (Bolerium), a grid of black-and-white figurative wallpaper, is visible through two storefront windows: 14 repeated, cartoon-like drawings derived from political imagery the artist discovered at the legendary radical bookshop Bolerium Books, located less than a mile from the gallery. The majority of the text has again been erased, unmooring the illustrations from their particular temporal moments to underscore the ongoing need to resist. Images such as a caricature of Marcos wearing falsified war medals, a Roy Lichtenstein-like brush mark painted over the White House, and a hand with an American flag wristband operating a marionette of a map of Nicaragua are juxtaposed.

The image of a hand, or its specter, occurs throughout the exhibition, beginning with the Romanian proverb that lends the exhibition its title. Through this symbol, Abad brings a human dimension, and a corresponding level of empathy, to this complex exhibition, which adroitly integrates art and politics. His focus on specific, intertwined lives in the Philippines and the US—Ferdinand, Imelda, Ronald, Nancy, Gene, Silme, Dina, even Kim and Leo—manifests the broad reach of the brutal dictatorship and the significance of the individual. But this emphasis on humanity does not offer any redemption. Instead, an air of gloom pervades the exhibition. Abad’s transformation of indisputable historical documents into arresting art objects suggests that the cyclical nature of politics is inevitable, a damning indictment in our current political climate. One need only note that in 2015 Imelda Marcos accused Donald Trump of plagiarizing her husband, who first declared “make this country great again” in 1965.