Olivia Plender’s research-driven practice is rooted in a fascination with the way communities self-organize—from activist groups, youth movements, and spiritualist associations to alternative education programmes and the offices of tech behemoths—and the strategies, labor, geographies, and architectures that enable (or obstruct) them. Her second solo exhibition at Maureen Paley recontextualizes texts, images, and actions relating to self-education and resistance, with the delicacy of several series of small drawings in black ink or charcoal pencil contrasting with all-caps wall posters proclaiming statements like “THEY WILL NOT DIVIDE US.” But in bringing together these slices from various projects, each of which has grown out of sustained historical research or community engagement, this exhibition is not always successful in communicating their richness or significance.

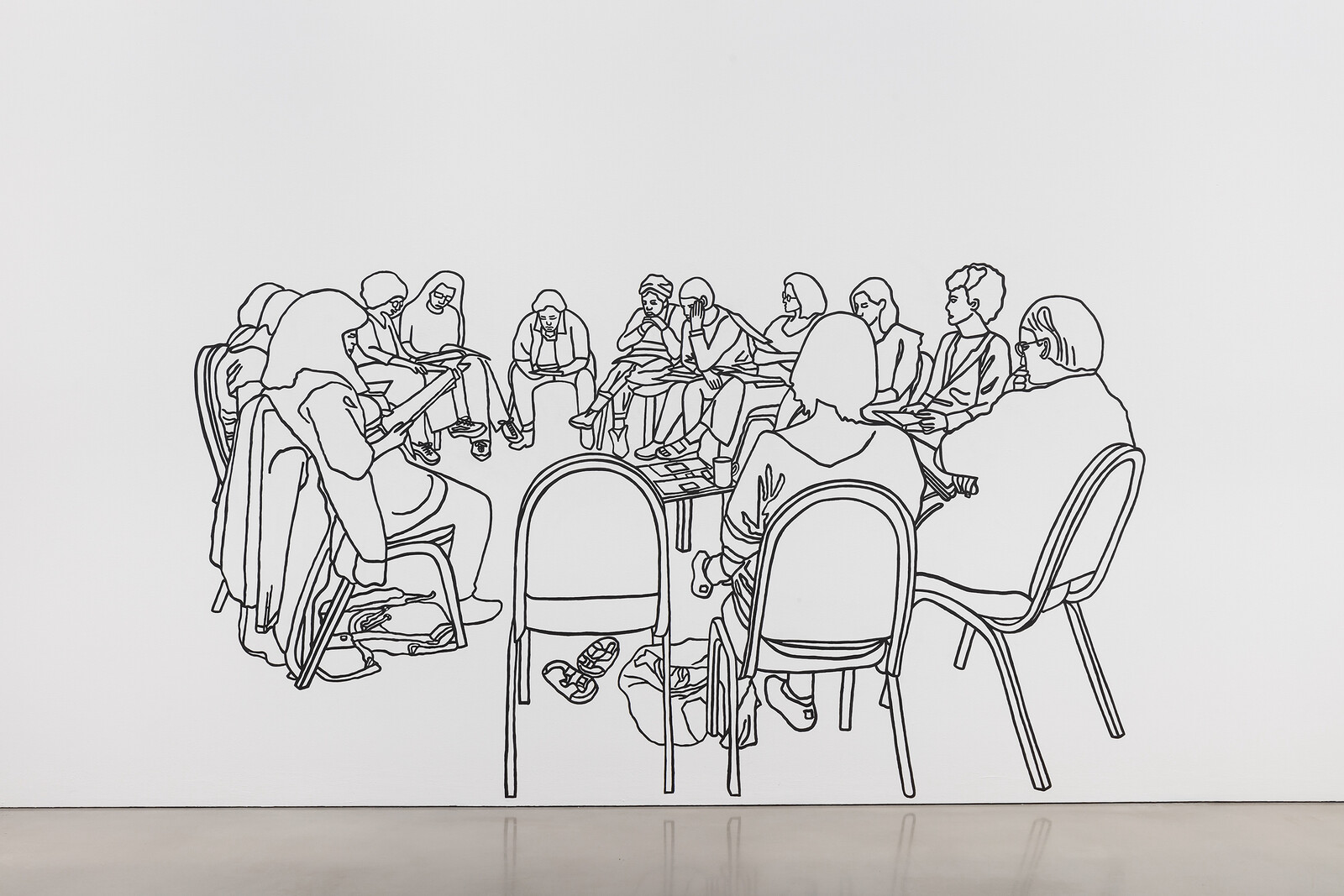

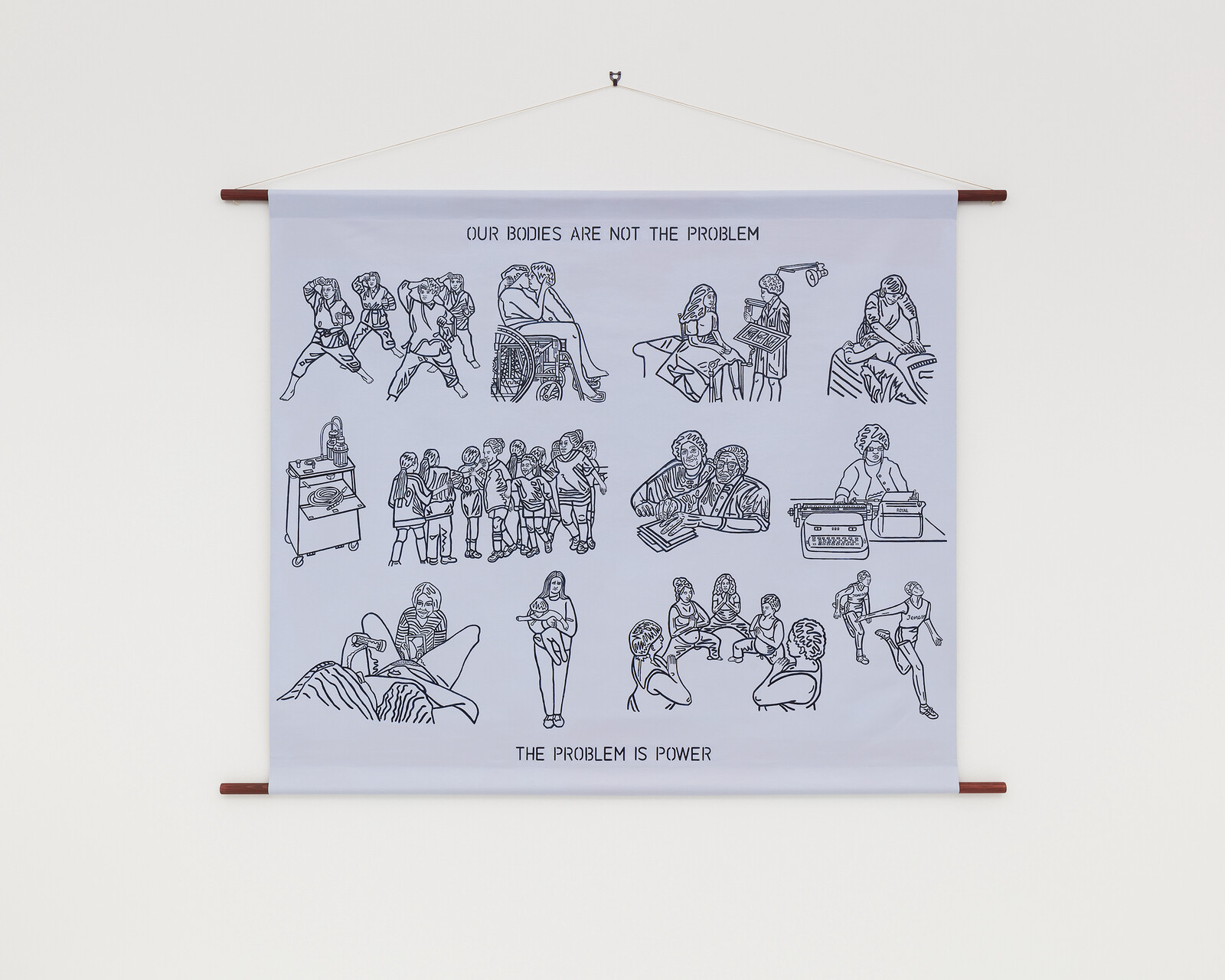

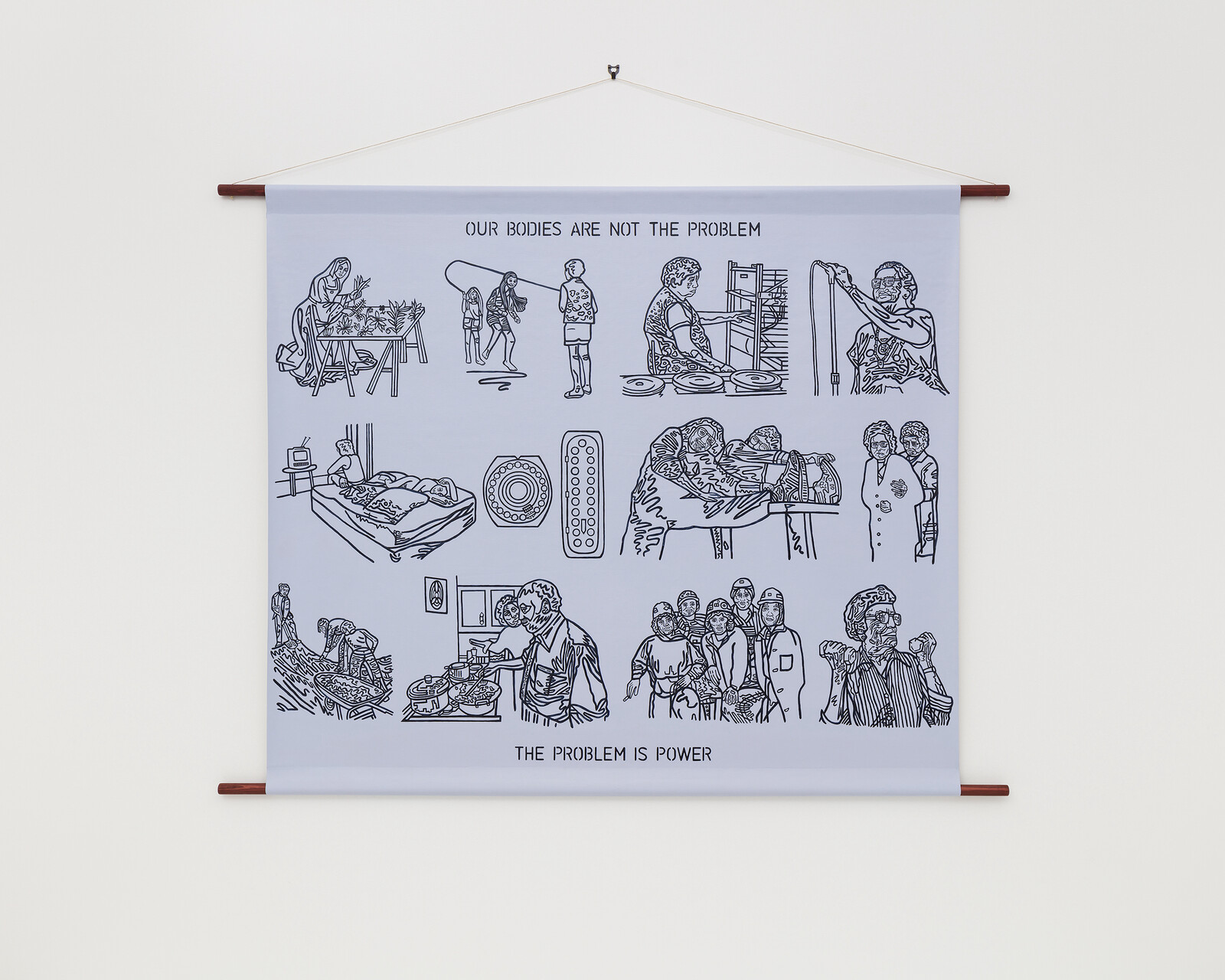

Plender takes great care in considering the spaces in which community organization takes place: she pays attention, for example, to the labor that goes into setting up for a meeting or tidying away afterwards. In 2021, she revamped the community room at Glasgow Women’s Library, transforming the upstairs area into one of welcoming softness. Plender’s life-size drawings are now emblazoned across a partitioning curtain. Floor rugs and jewel-toned bean-bags offer comfort for those wishing to sit or lie, while the walls and ceiling are a fabulous lilac colour. That tone is an allusion to the term “lavender menace,” once a slur used by feminists attempting to exclude lesbians from the movement, then reappropriated in the 1970s as part of the struggle for a more inclusive feminism. At Maureen Paley, Plender’s engagement with Glasgow communities is represented by three acrylic paintings on canvas, hung between horizontal wooden dowels, which show women running, kissing, campaigning for trans healthcare, arranging flowers, doing judo, having a chat and a smoke. In the small side gallery they seem a little lost. The significance of their lilac backgrounds—made explicit in the GWL iteration— goes unmentioned here, making it easier for viewers to miss the depth of Plender’s research.

Neither Strivers Nor Skivers, They Will Not Define Us (2020) is more effectively presented. The project takes as its starting point a play written by Sylvia Pankhurst in 1913, which Plender found in the archives of the Women’s Library in London. The play centers on suffragist Mary, who knocks on doors in an east London tenement, is force-fed by doctors in a hospital prison cell, receives visitors to her sickbed, and finally leads a (triumphant) march on Downing Street. In Plender’s book, published by The Bower, Pankhurst’s play is reproduced alongside edited transcripts of conversations among groups of women actively resisting the anti-immigration “hostile environment” policy enforced by successive Conservative governments in the UK. Neither Strivers Nor Skivers sets up an obvious parallel between the gross inequities of pre-war London and those currently being exacerbated by years of right-wing austerity and repressive policing.

Formally, the dialogue through which both play and group meeting are presented encourages readers to wonder about the political efficacy of realism. Much of Plender’s work, after all, is fundamentally realist, although at its best, it does more than depict: in the book, the women read and discuss Pankhurst’s play and the ways in which it relates to their own experiences, even rewriting one scene in order to emphasize self-organization rather than dependence on a white middle-class savior. In this new context, a text is no longer a historical artefact: its purpose shifts from suffragette recruitment tool to case study in community organizing.

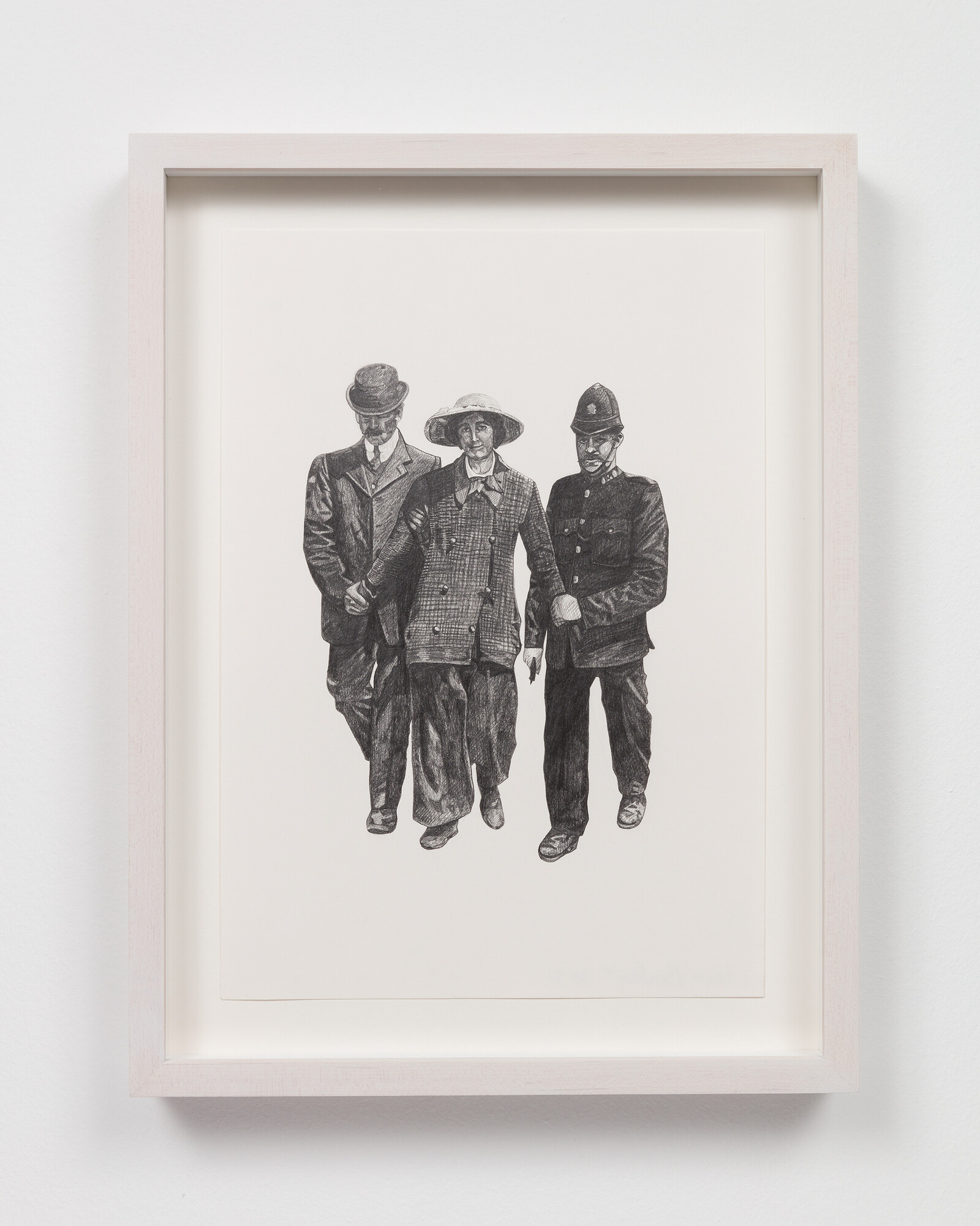

Plender’s practice is consistently questioning, sensitive, and politically vital. The exhibition’s most powerful moment comes when two bodies of work overlap. In addition to the publication, Neither Strivers Nor Skivers is represented via an installation of sound, posters, and wall painting. The audio contains extracts from the publication, individual testimonies, and sounds of public protest. Nearby hangs a series of seven pencil drawings of suffragettes being arrested by police (Arrest!, 2021). Plender has taken images from multiple times and places (protests in Dundee 1910 and London 1913) and removed contextual specifics (biographies, image sources, et cetera) in order to focus on the women’s bodies in the moments of their arrest by male policemen. The result is a series of images of bodily resistance floating on white pages in a white gallery. One woman digs her heels into the ground to resist three male officers, her mouth open wide in fear or anger or pain. Another woman gazes towards the camera/artist/viewer with a calm, inscrutable directness. You can see what is happening, her expression seems to say, so what are you doing about it? “Shame on you,” echoes out from the speaker above. The link between the suffragettes and those fighting for basic rights today is clear: Plender, who has repeatedly drawn attention to the People’s Army, a self-defence group founded by the East London Federation of the Suffragettes, is issuing a powerful call to arms.