Only someone with a lying mouth, according to Yoruba oral tradition, would speak first and look for visual confirmation second.1 Untold centuries later, the expression retains its value: photography’s maneuvers depend on the fact that truth is determined by the eye.

The complete history of photography is inextricable from colonialism in Africa—its establishment, rule, and dismemberment. The practice was introduced on the continent almost immediately after its invention, disseminating quickly. Some of the very first silvery daguerreotypes captured Egypt’s grand wonders in the 1840s; by 1853, African-American Augustus Washington had opened Liberia’s first studio in the capital Monrovia, and Senegal’s by 1860. The medium was slower to spread into Yorubaland, taking up until Britain’s drawing of modern-day Nigerian and Beninese borders at the turn of the twentieth century, but the photograph was folded into both ancient custom and contemporary society so neatly that it expanded beyond document and into identity architecture. The staged portrait was a highly orchestrated image, a manifestation of oriki, the Yorubian ritual of lauding someone’s character by making them a subject of praise poetry: a man during odo (midlife) sits alone in traditional dress at the very center of the frame, facing the lens, with a vertical panel draped behind him to underline his presence.2

This formal stylization became the standard in the region and, by the early 1940s, Seydou Keïta updated the aesthetic for his own generation in Mali. Men, women, couples, and families came to his studio to be carefully composed in front of his camera, wearing their noblest clothing and expressions. Men often wore Western suits, while women wore modest floor-length dresses in traditional fabrics. Aspirational props were on offer, including European clothing, radios, and watches. The portraits lightly reflected modern African society’s changing aspirations of international glamor and modernization, but they often predated—or overlooked—the era’s exhilarating revolution and bounce.

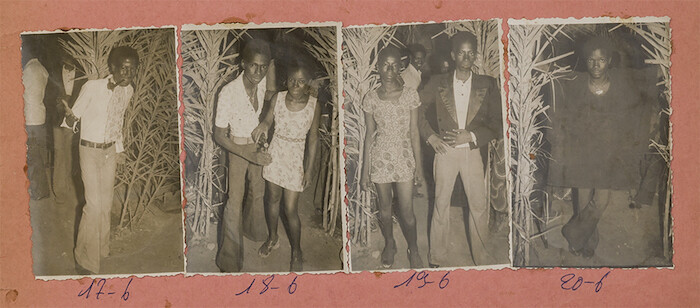

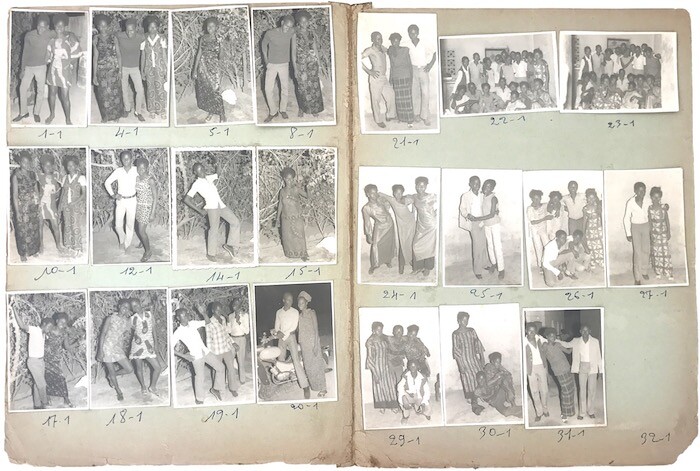

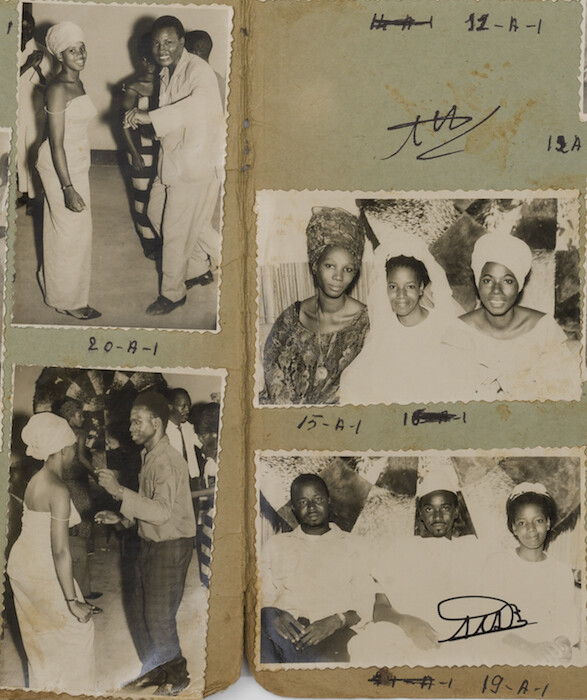

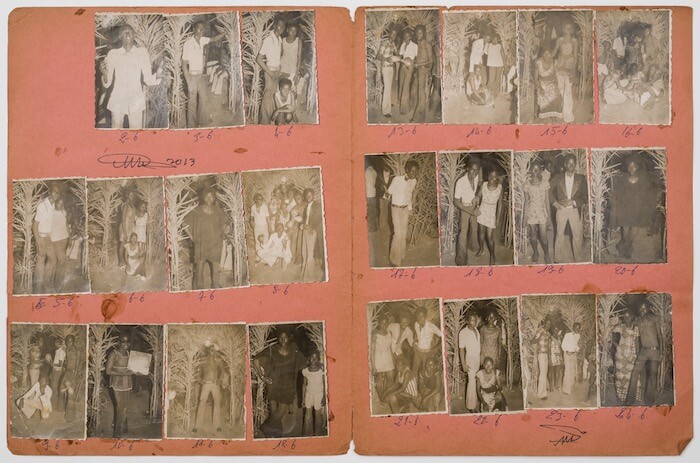

By the 1950s, consumer technology and cosmopolitan culture were quickly evolving. Drum, a weekly South African magazine on urban life and culture, began covering everything from Lena Horne to apartheid in its pages. French photographer Gérard Guillat hired Malick Sidibé, a young graduate of the School of Sudanese Craftsmen, a scholarship student (responsible, at the age of five, for herding sheep in Soloba) who was chosen by his tribal leader to attend the “white school” in town. Apprenticing in Guillat’s studio in Bamako, Sidibé bought his first camera, a Brownie Flash, in 1956. By the time Studio Malick opened in 1958, the equipment’s portability unbound him from his workspace, and so he was free to follow dynamic tableaux outside of it: neither he nor his subjects were interested in the artifice and ceremony of past portraiture. Instead, he paid visits to the high school students in Africa’s capital cities who gathered into “grins,” social clubs ostensibly organized for team sports. Bamako’s youth bunched up in basements and cafes to trade zines, listen to records, and discuss politics. He attended weddings and christenings, and party-hopped between Les Beatles or Casa Tropicana on Saturday nights to shoot the ecstatic, warm serial black-and white snaps he became known for; he was his peers’ griot. The 35mm lens’s reliable, nimble rate of exposures and relative affordability allowed for an impressive number of photographs on the go; he would often return to the studio after a party to print the evening’s photographs for the next day. It also accounted for Sidibé’s methodical visual notation covering the fine points of an entire evening, from the pleasant, shy mannerisms of guests’ arrivals and introductions to their bombastic shimmies to the last, balmy, midnight sways.

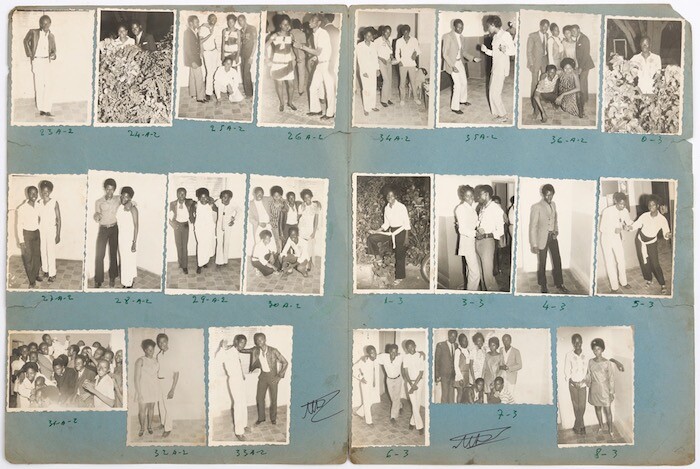

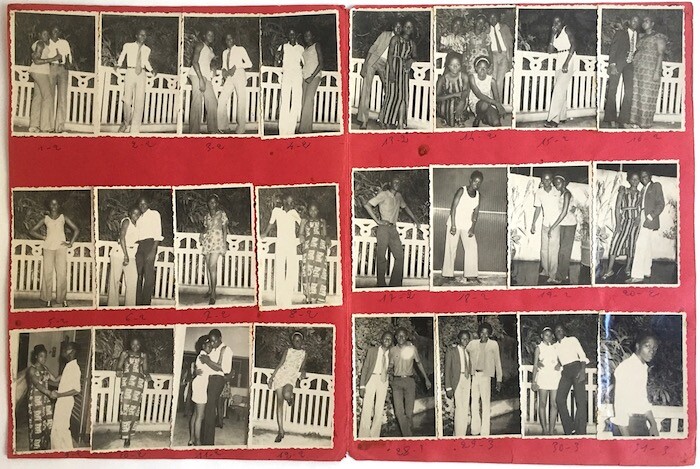

The collections on view at M+B—clipped, orderly lines of party scenes on 35mm film tacked onto crimson or sage or azure paper and annotated by hand and fading—are stylish eyewitness testimony to an emerging Bamako. Friday night (Nuit du 22-9/72, 1972) had all of its brimming prospects on display: couples sporting bellbottoms pulling up to the scene on a Vespa or sweetly holding hands, friends dressed and posturing in synchronicity, dancing to the latest record, sighing secrets to each other while leaning on a parked car. Les “Intimes” de Bagadadji (1971), a survey of characters in the neighborhood of Sidibé’s studio, is evidence of a youthful transition, as some wear traditional dress while others wear mod styles one might expect to see in London nightclubs at the time; a pineapple-printed minidress commingles with a boubou.

In 1960, Mali’s independence from France, and consequently, the French Sudan, was the beginning of this new republic, and Sidibé archived his generation’s optimism and interest in popular culture during its pinnacle in the 1960s and ’70s, though his work, like that of Keïta’s, was not exhibited outside of Africa until the mid-’90s. It is not enough to only distinguish his from that of other photographic practices in Africa, but against the image of the continent that had often been sanctioned, spurred, even, by the West—one of monotonous civil wars, famine, or poverty. “Chemises” also has felicitous timing, as overwriting narratives of African and African-American presentation and representation are on view in diverse and abundant forms. In Los Angeles alone, the nerve center of positive affirmations, MOCA hosts touring exhibitions by Kerry James Marshall and Arthur Jafa; the Fowler Museum has a survey of African print fashion and photography; the Underground Museum wraps a year-long exhibition of work in which contemporary practitioners examine the black body within America’s violent racial history.

Skeptical theorists and academics within the diaspora were concerned about an underlying neocolonialism visible in Sidibé’s photographs: teenagers in Françafrique appeared to be seduced by American popular music and European fashions, in denial of their negritude and historical tribal loyalties. Instead, they were expressing themselves in diaspora aesthetics3: asserting their state’s political independence would not come at the cost of their new social liberties, and they upheld a greater Pan-Africa and inclusion of intimate freedoms that had been depressed by centuries of Arab or French imperialism. While Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire delineated postcolonial identity and obligation, music like James Brown’s set the body in dance free again—to be rhythmic, in worship, or disobedient. Freedom has no provisions.

Adélékè Adéè̇ó, “From Orality to Visuality: Panegyric and Photography in Contemporary Lagos, Nigeria,” Critical Inquiry, vol. 39, no. 2 (Winter 2012): 330–361.

Stephen F. Sprague, “Yoruba Photography: How the Yoruba See Themselves,” African Arts, vol. 12, no. 1 (November 1978): 52–59, 107.

Manthia Diawara, “The Sixties in Bamako: Malick Sidibé and James Brown,” Andy Warhol Foundation Paper series on the arts, culture, and society, no. 11.