Capturing the unseen has been a taking-off point for photographic ambition since the medium’s inception. Ephemeral moments, underlying truths, and the supernatural have all been teased out through choices around opening and closing shutters. Featuring small-format photographs produced from the mid-1950s through the early ’70s, this exhibition at Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, posits Ralph Eugene Meatyard as an eccentric visionary who pursued and even contrived to generate signs of humans’ unseen and uncanny relationships.

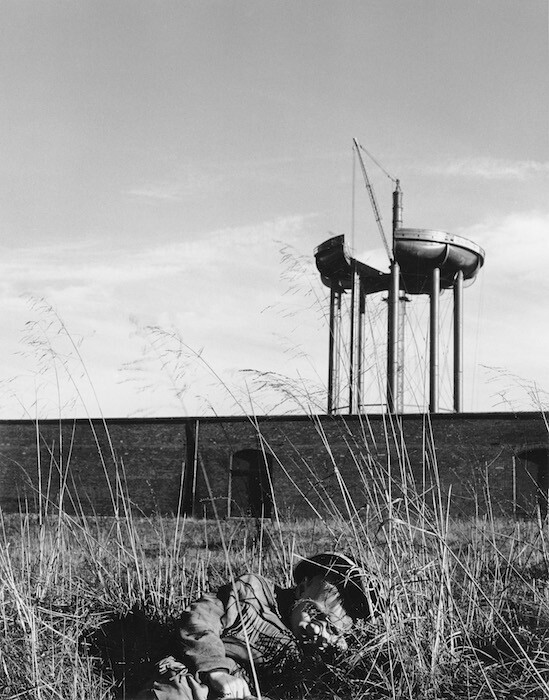

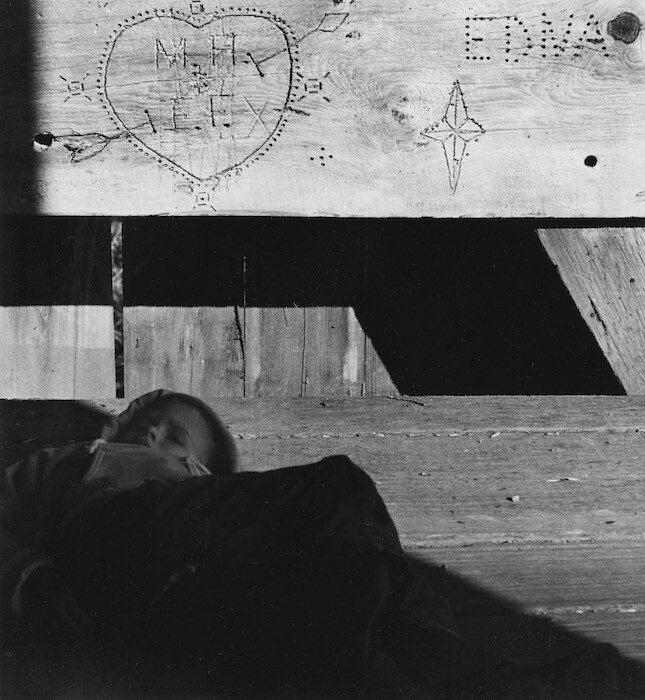

The black-and-white tones in Meatyard’s photographs hold forth something immanent that is not quite real, lived life. The choreography for his images—almost all of which deny clear viewing, by one means or another—play on the voyeuristic aspect of photography. The obscured and recumbent human figure is one recurring posture that Meatyard set up and captured, often with the suggestion of other figures above or nearby (at the very least, the implied viewer/photographer). This is the case with the buckskin-dressed boy half-sprawled in tall weeds below a hulking water tower in Untitled (ca. 1955); in Untitled (1960), sunlit graffiti carved on a slab of wood confronts the viewer as if from the fever dream of the boy over whom it hangs, immediately above the dark shade in which his just visible head recedes.

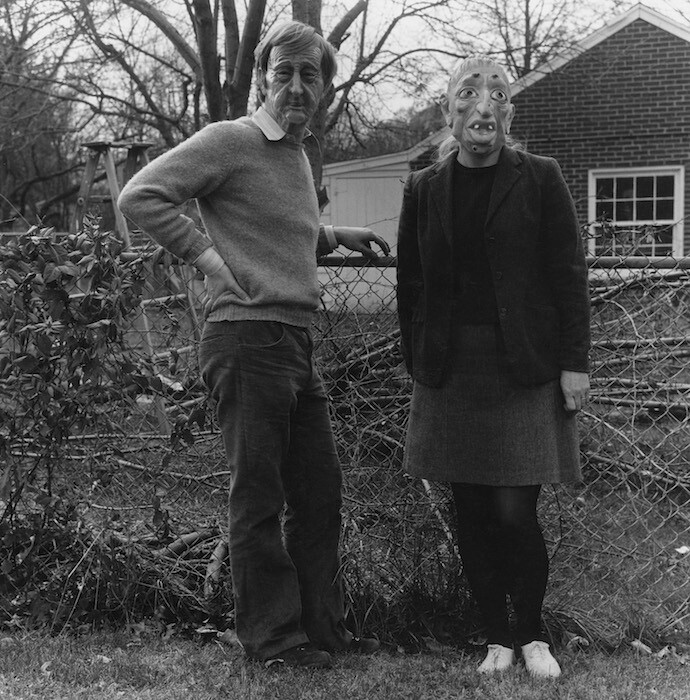

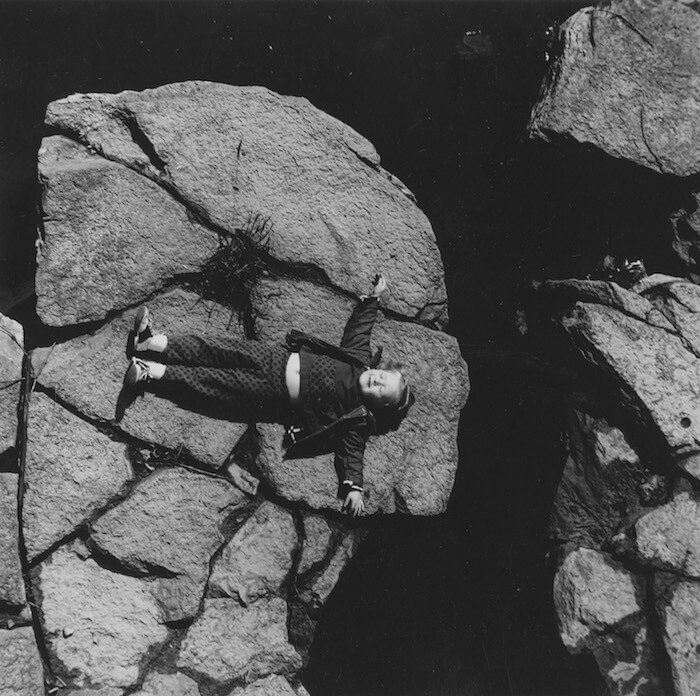

There is frequently something awkwardly and even perversely erotic in the figures depicted by Meatyard. So many young bodies: children splayed on rocks; adolescents half-hidden from view by foliage, shadow, and elements of architecture. Even with his adult models, a coy sort of peek-a-boo occurs: the bared legs and clothed curves of his wife’s body under skirts and sweaters, her face hidden by a strange, encompassing mask, as in 15 photos from Meatyard’s fictional sequence “The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater” (1970-72). Along with the use of physical masking, this longer “photographic poem” further shifts the identities of individuals—known to the photographer and his wife in real life—through occasional hand-scrawled captions on the prints themselves.

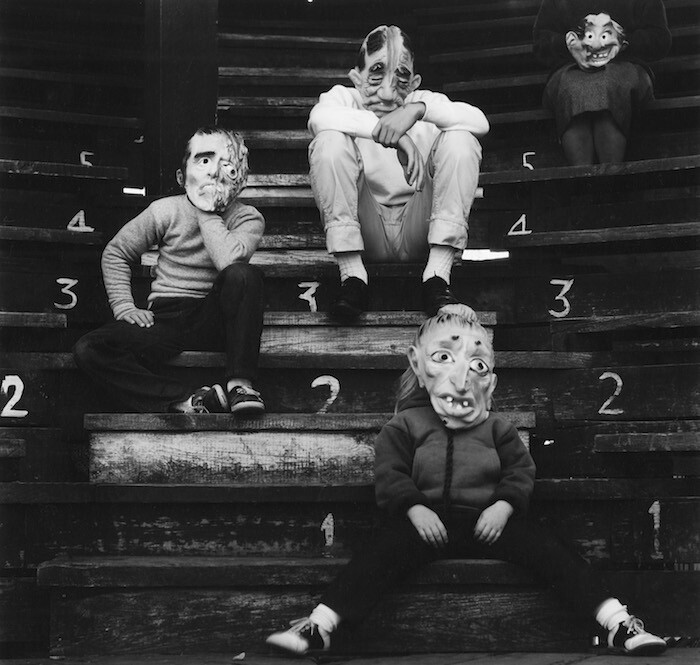

The monstrously distorting masks worn by many of Meatyard’s subjects are even more grotesque when mismatched with the gender and age of their bearers (e.g. Romance (N.) from Ambrose Bierce # 3, 1962). While flirting with partial anonymity, telltale signs of body and dress still say something about their bearers. Extended re-contextualizations of the figure of his wife—both through her hidden, distorted face, and by placing her as one half of a series of other couples in mundane tableaux—suggest the simultaneity of attraction and repulsion; the unknowability of others; and an underlying, dark spirituality to ordinary lives. Yet something more evanescent hovers beyond these already ambiguous interpretations of those signs of reveal and conceal which are seemingly at cross-purposes in Meatyard’s photographs.

His decision to cover his models’ faces denies not only individuality but intimacy. These are not the enticing and disinhibiting masks of Rio Carnival but darkly libidinal occlusions and projections, shot through with hints of interpersonal failure. Their startling uncanny suggests a crepuscular American Gothic mythology akin to horror movies, or—given the all-white subjects and basic, Midwestern Americana settings—the Ku Klux Klan. The artist also wrought other “masks” through composition and technique: blurring subjects’ faces with shadow, movement, intervening objects, and bodies inclined away from a fuller view, as with a boy’s face half-erased by the grillwork in front of a mausoleum in Untitled (1955).

Abstractions in various degrees of black, white, and gray—the small fireworks in Untitled (Portraits of Self) (1960), or the foliage in some of the selections from “The Unforeseen Wilderness” series (1967-71)—highlight the tonal range of his images featuring human figures. Slabs of off-white and dusky slate oblongs commingle with clear-cut darks and lights. Images of mortuary statuary, weather-brushed of expression or affect, stand in for the equally mysterious humans who appear elsewhere in Meatyard’s conceptions. In both, sightless eyes stay closed in internal reverie or avoidance of something outside, blinded by light or obscuring bands of shade: asleep or dead. Meatyard’s physical masks serve the same purpose, making a mockery of human emotions by blowing them up into monstrous cartoon versions or belying altogether what might be underneath.

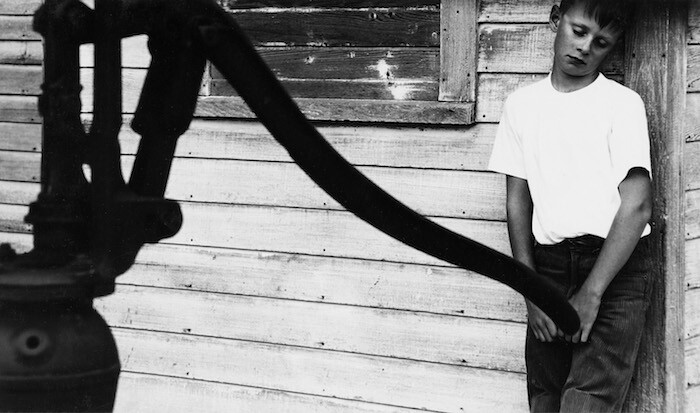

The question remains: if Meatyard was a mystic, what was his vision? How to read humans’ relations to their internal and external worlds in the off-white mass representing the torso of a boy seen from behind in Untitled (1961), his bowed head hidden from view, set in a field parallel with the beached gunnels and hulking trapezoid of a rowboat stuck in overgrown foliage on land? And what is the nature of reality suggested when he frames a huge water pump handle as if emerging from the crotch of a pubescent boy in Prescience (1960)?

What were Meatyard’s motivations in projecting his peculiar ethos onto others? Are the masks the signs of the horror that lies below the surface of quotidian, even stultifying, daily life? Or icons of some other phantasmagoria, psychic overlays on the milieus he shot—a decaying middle America dotted with abandoned buildings and mausoleums, or main street storefronts and suburban sidewalks threatened by decrepitude and obsolescence? Cognitive residues from these haunting images persist unresolved, at once seductive and unsettling.