It is impossible to separate my experience of Yara El-Sherbini’s “Forms of Regulation and Control” from the circumstances surrounding the viewing: the end of a balmy November day, awash with the jubilation of Donald Trump’s electoral defeat. The first US solo exhibition for British-born, Santa Barbara–based El-Sherbini, curated by Naeem Mohaiemen, is an elegant rejoinder to the din of recent months. Deftly weaponizing humor through a series of discreet interventions, it challenges the so-called “unconscious” bias that permeates even the most seemingly benign forms of knowledge and their production.

“Forms of Regulation and Control” is an exhibition conceived and reconceptualized in the wake of the pandemic; El-Sherbini’s work, usually tactile and interactive, is incompatible with our current socially distanced reality. The game “Border Control” (2017), the only pre-pandemic piece in the show, is an example of the kind of audience participation El-Sherbini usually employs. In something reminiscent of the children’s game, players must trace a charged metal wire shaped like the US-Mexican border with a circular metal tool, all the while avoiding making contact with it: if they do, they will sound off alarms and lights. And yet the way in which the exhibition has been reimagined serves to highlight the mischievous humor at the heart of the artist’s practice, now only heightened by the absurdity of “the new normal.” In “Occupied/Freed” (2020), El-Sherbini tampers with the gallery’s bathroom door, replacing the occupancy-indicator lock with her own revised labels. A trip to the toilet is thus transformed into an act of occupation, the small cubicle becoming a site of political aggression. However, in an unexpected twist, since the bathroom is closed to outside visitors for safety reasons, we are prevented from occupying and the area remains—for the most part—liberated.

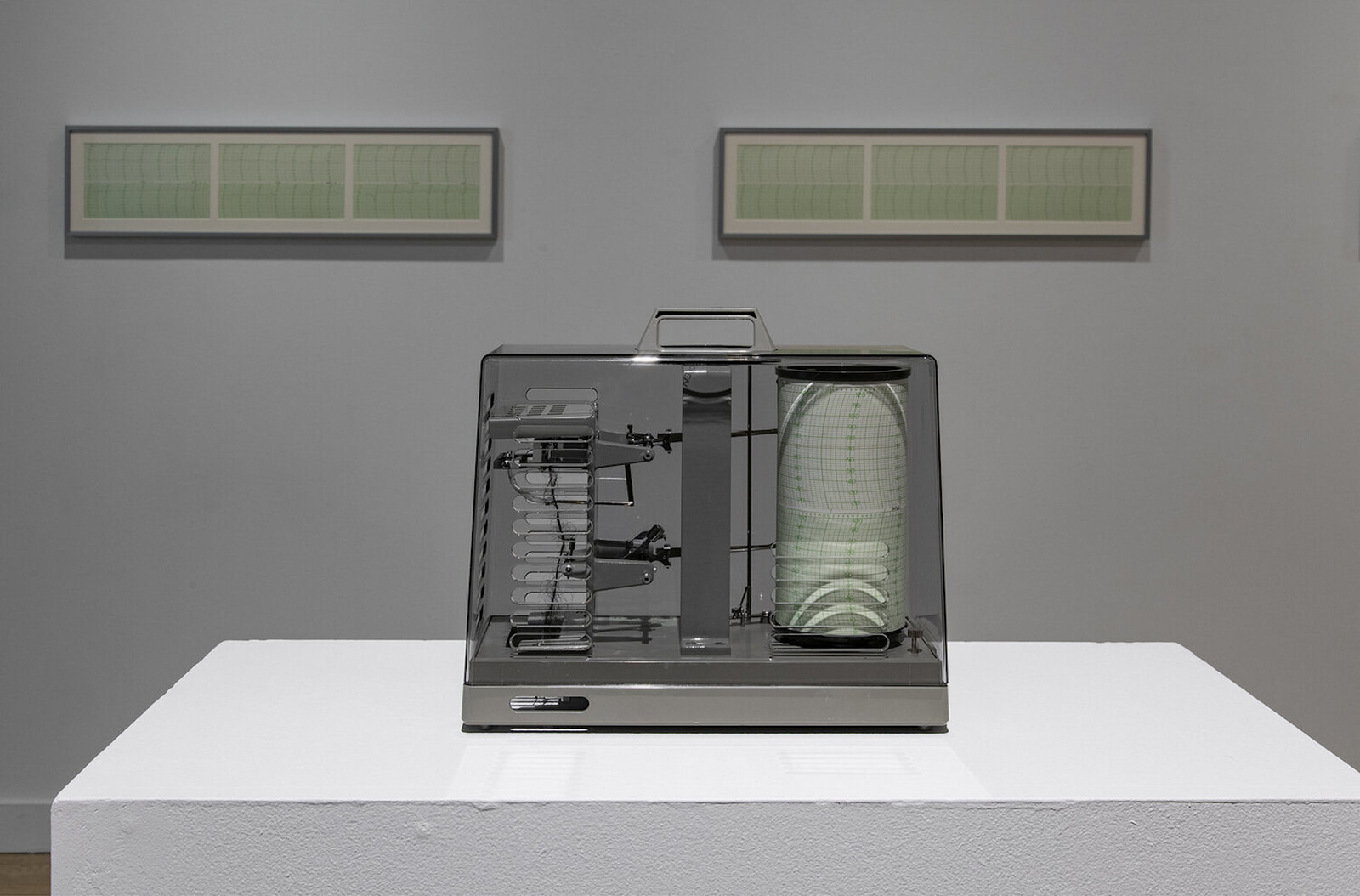

In the wake of this summer’s Black Lives Matter protests, cultural institutions, including major American art museums, have scrambled to proclaim their support for the movement—even as they laid off their own workers—by briefly giving over their homepages to diligent reassurances of their intention to address racial inequality, which for the most part merely gesture at the degree of their complicity with, and inseparability from, the systematic racism that has historically enabled their foundation and survival. In “Other Forms of Regulation and Control” (2020), El-Sherbini displaces three hygrothermographs from their usual location, hidden in the building’s margins, elevating them on pedestals placed in the center of the gallery. The gray metal machines with their plastic casing and green graph paper appear cool and clinical, giving the room a somber and serious air.

Hygrothermographs are intended to measure and help control the temperature and humidity of the space so as to stabilize conditions and protect the works; they typically collect this information by using a piece of human hair, marking the variations on graph paper. In an example of what El-Sherbini refers to as a “gently subversive approach,”1 she modifies two of the hygrothermographs, replacing the standard “Asian” hair—commonly used for its straightness—with “African” and “Caucasian” strands respectively. The “findings,” recorded for the duration of the exhibition, are framed and displayed on the opposite wall, updated on a weekly basis. Mimicking the scientific categorizations that produce ethnic and racial difference, “Other Forms of Regulation and Control” gestures to the inextricable histories of museology and European colonial expansion. Embedded in its very infrastructure, the museum relies on racial categories to function and regulate itself and others. All the while, the machines tick incessantly, reminding us of the omnipresence of surveillance and the never-ending accumulation of data, as well as the racialized and racializing nature of both.

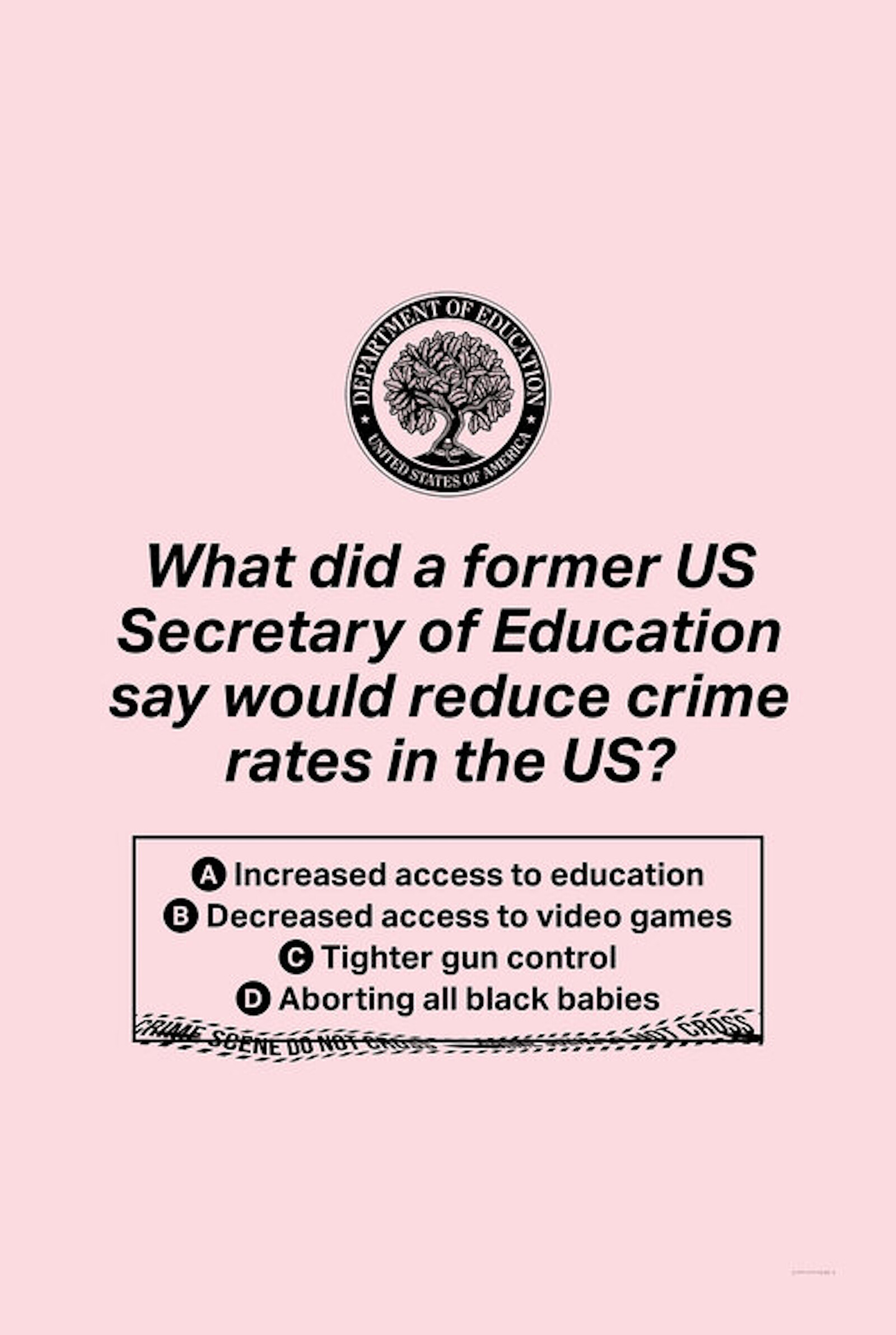

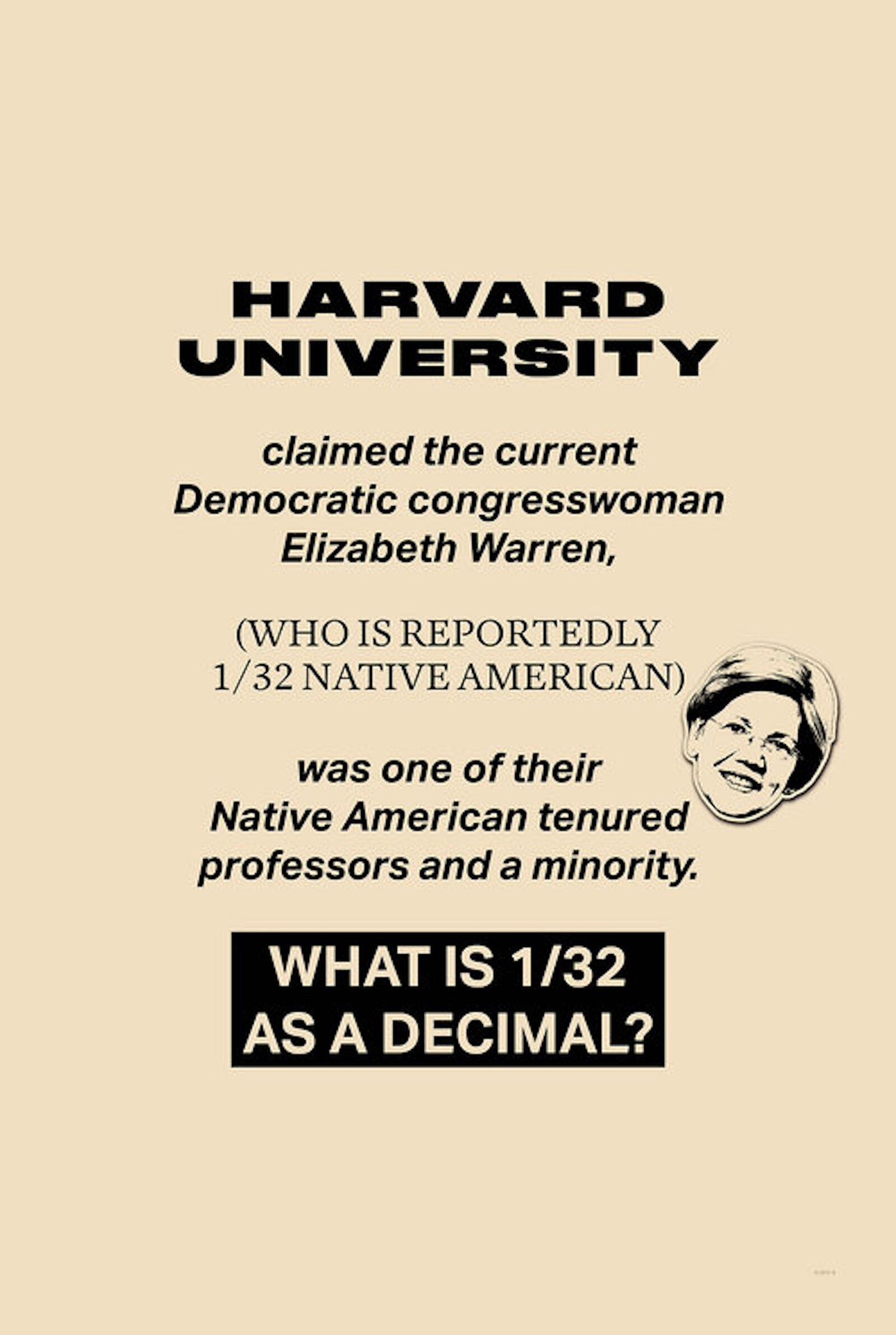

For the past decade, El-Sherbini has hosted an intermittent, roving pub quiz, writing her own questions and serving as quiz mistress. The event itself has moved to Zoom, but “Questioning” (2020) is a translation of the performance onto the gallery walls; a series of large inkjet prints featuring purported quiz questions greet visitors as they enter the space. Brightly colored, with large fonts and amateurish clipart, their aesthetic is cheerful and disarming. However, the text—questions that parody the innocuous style of trivia—present the stark realities of today’s political landscape. “What did former US Secretary of Education say would reduce crime rates in the US?” one print reads. “A: Increased access to education, B: Decreased access to video games, C: Tighter gun control, D: Aborting all black babies.” Rather than detract from her critique, El-Sherbini’s use of humor accentuates it; that D is simultaneously the only possible/impossible answer succinctly captures so much about the current moment in the US.