The “unfinished return” in the title of New York–based artist Cici Wu’s first solo exhibition in Hong Kong refers to a legendary incident in the city’s recent history. In August 2000, Yu Man Hon, a 15-year-old autistic boy, was separated from his mother in an MTR metro station in Kowloon. Somehow, the young man made it to a checkpoint at Hong Kong’s border with Shenzhen, where he was able to cross into Mainland Chinawithout identity documents. Once on the other side of the border, unable to make his way back to Hong Kong, Yu disappeared, never to be found.

For many, the story of Yu resonated as an allegory of Hong Kong’s relations with Mainland China in the early days following the handover of the former British colony to the People’s Republic of China in 1997. There is indeed the shocking indifference of the authorities, especially in dealing with the most vulnerable. But there is also the sense of loss, of blurred national and cultural identities, and of the border as a liminal zone where one’s very body might dissolve into evanescence. Revisiting the story some 20 years later, Wu’s exhibition ponders the cultural resonance of Yu’s ambiguous fate, even offering a speculative dénouement to the mystery, staging Yu’s reappearance in Hong Kong as an altered, ghostly presence in a city that has itself irrevocably changed.

Located across the 18th and 19th floors of the Grand Marine Center near Aberdeen Harbour, Empty Gallery draws visitors from the building’s elevator and straight into a very dimly lit antechamber, which leads to an almost hidden corridor that connects to the gallery’s similarly shadowy foyer. The darkened network of passageways at first resembles a labyrinth more than a gallery, but the experience is more seductive than claustrophobic. Sharing the space with another solo exhibition (by the artist Tishan Hsu), Wu’s show is accessed by descending a flight of stairs into the gallery’s lower level, where viewers follow the dim glow of Wu’s light sculptures and video projection, and its soundtrack, a dense collage of fragmentary voices and chiming bells.

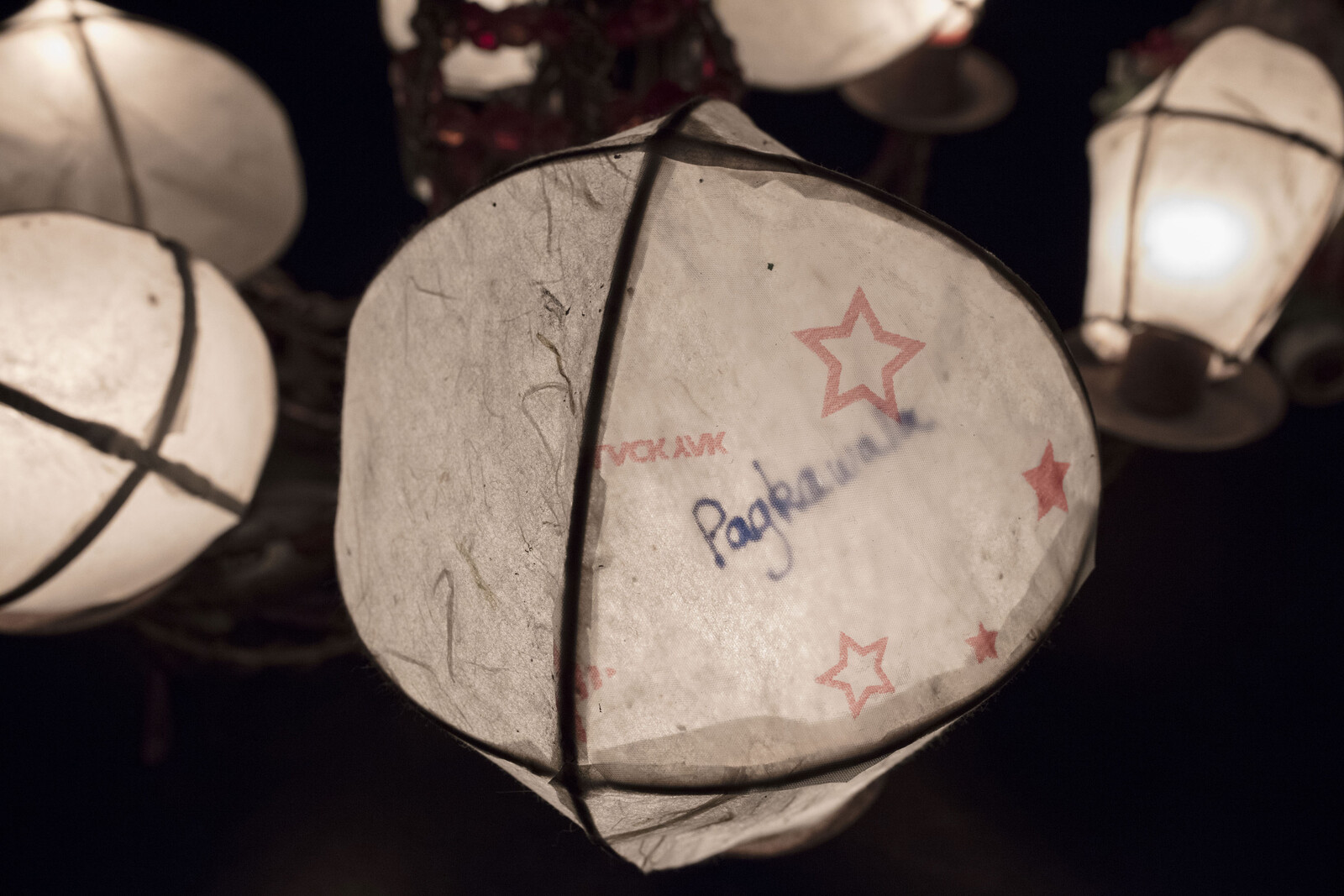

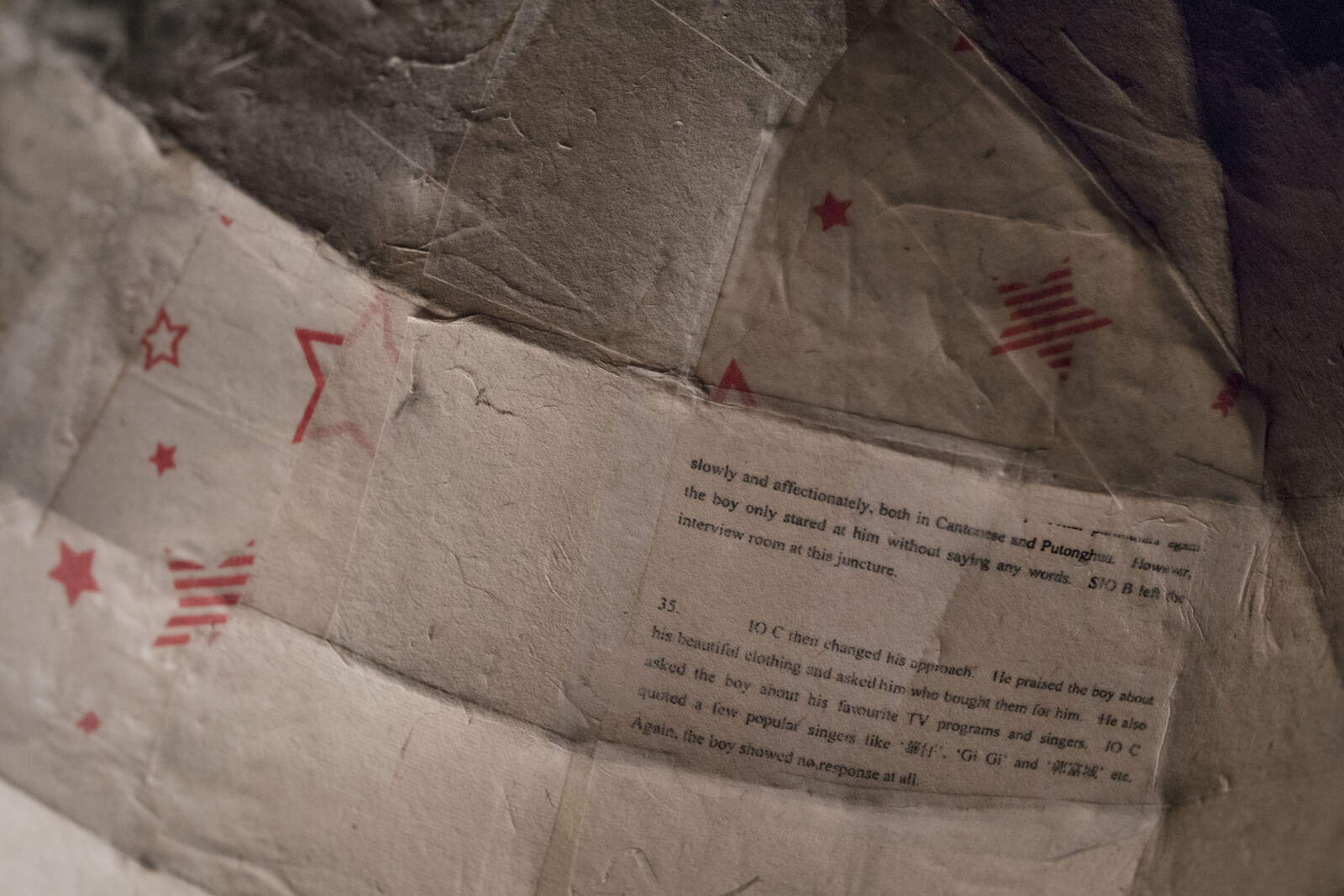

Entitled The Unfinished Return of Yu Man Hon (2019), the video forms the centerpiece of the exhibition. which also includes a series of mixed-media light sculptures. Indeed, the video is itself an assemblage, mainly filmed on 16mm (with some VHS home-movie footage), and compositing discrete sequences of a young man, presumably Yu, traversing a set of diverse transitional spaces (airport, bus terminal, metro trains, ferries) in a distinctive knit wool cap. Pushing the threshold of the analog film’s capacity to register its images, Wu frequently finds the young man’s figure dissolving in a haze of blue-white-pink light or blurring into the background as he’s captured in fogged-lens images of snowy landscapes, or the chaos of an MTR station or busy marketplace. In a surrealist flourish, Yu is also accompanied on his journey by a small cow constructed from glued paper on a bamboo wire frame, and featuring photocopied scraps from the official police report on the disappearance pasted onto its hide—which is also exhibited alongside the other sculptures.

The presence of this cow—as a sculpture titled Memory Cow (2019)—in the gallery space, and the ambient illumination offered by the light sculptures to complement the video projection, creates a subtle sensory link between the objects and images that Wu has brought together here. These mixed-media sculptures—delicate, hybrid constructions from paper, bamboo wire, plastic film-prop chandeliers, and assorted found ephemera—bear titles such Subtitle 01 (Justice and Hope) (2019) and Subtitle 01 (Forgotten to Forget) (2019), further hinting at processes of linguistic and cultural translation at play. In a sense, these objects bridge the ephemeral and imaginary spaces onscreen and the material and historical worlds to which they allude. Further scrambling these distinctions, Wu adds an intertextual layer by casting for the role of Yu the Taiwanese actor Jonathan Chang, most widely known for his part, at age nine, in Edward Yang’s exquisite family melodrama Yi Yi (2000). Wu’s video even cites a small fragment of Yi Yi’s soundtrack—the heartrending moment at the end of the film in which Chang’s adorable adolescent character, dressed in a tuxedo, reads a letter to his recently departed grandmother at her funeral and wonders, “Perhaps one day I’ll find out where you’ve gone.” Thus, even the biography of the actor becomes curiously entangled in the mystery.