Twenty years after the handover of sovereignty from the United Kingdom to China, Hong Kong stands at a crossroads. The generation to come of age in the intervening decades has become restless, frustrated by the rejection of demands for universal suffrage (the election for the next Chief Executive takes places tomorrow, March 26, but only 1194 people have a ballot[1]). That, along with sky-high property prices and low social mobility, has fueled a cycle of disenchantment that has set the territory on a collision course with Beijing. Feelings are running high.

Art Basel Hong Kong stands at some remove from all this, but is nonetheless pervaded by a sense of urgency. Presented by 10 Chancery Lane, Hong Kong and P.P.O.W., New York, in the Encounters section, which hosts large-scale sculpture and installation, Dinh Q. Lê’s The Deep Blue Sea (2017) distorts news images of migrants crossing the Mediterranean to seek asylum onto 150-foot-long stretches of photo paper. Transforming photography into sculpture and creating an alluring installation redolent of streams and waves, the work digs into media (mis)representations of the refugee (the figure of which, as Giorgio Agamben has famously argued in his 1995 book Homo Sacer, removes the fig leaves of political and moral systems, revealing the “bare life” of the human as an animal without rights). At Taro Nasu Gallery, Tokyo, Simon Fujiwara’s “Masks (Merkel)” (2017) series tackles the nexus of politics and media in an unusual way: the artist creates paintings in a pinkish skin tone of deep close-ups of Angela Merkel’s face by using the same cosmetic powder the chancellor uses, a work done with the help of her personal makeup artist. The indexical relationship engenders a strange intimacy. Viewers have an abstracted close-up of a gendered ritual of self-construction at once fundamentally private (putting on makeup) and highly public (image-making).

Humanity’s impact on nature exercises the imagination of several artists in the fair. While the Anthropocene is a term much bandied about at the moment, it does provide a useful way of considering the divide between nature and culture, or artifice. In the Discoveries section, devoted to showcasing emerging artists, Dittrich and Schlechtriem, Berlin, presents Julian Charrière’s “Coconut Lead Fondue,” a project that creates nature-culture hybrids, encasing coconuts in lead sarcophagi (Pacific Fiction, 2016). The coconuts were taken from an exploratory trip to nuclear landscapes in the Bikini Atoll, following from Charrière’s investigations of Soviet nuclear test sites. The swashbuckling romance of exploration is, thankfully, kept in check by a conceptual discipline and rigor. It also helps that Charrière’s works have a taut formal beauty: spectral clouds from radioactive dust left on negatives clash with actual clouds in the images, hinting at uncertain origins. Part of the Kabinett section, in which galleries delineate a space within their booths for a curated exhibition by a single artist, Yuko Mohri’s “Urban Mining series” at Taipei’s Project Fulfill Art Space offers a more intimate take on the topic. Using everyday objects (some recycled), Mohri creates mini-ecologies that link up causal movements (magnetism, wind, rotor cycles) with electric generation—like a domino setup or rolling ball sculpture, but recurring and sometimes with natural inputs. In her disruptions of how mundane objects work, the artist seeks to upset notions of the “natural” and the “artificial” in cause-effect relations.

If the above work is a light footprint in nature, then Zhao Zhao heads out with metaphorical guns blazing at Tang Contemporary Art, Beijing. His Project Taklamakan (2016), consists of a video that documents how the artist and 30 members of his team strung 100-kilometer-long cables along a desert highway, through a poplar forest, to the center of the Taklamakan desert in northwest China, where he filled a refrigerator full of Sinkiang beer and ran it for 24 hours. It might be tempting to read a “Chinese” view of nature here—in the sense of an unreconstructed “pre-post-modern” (or “modernity 2.0”) faith in the power of science and progress, a faith scarcely encountered anymore in the West, outside of Silicon Valley. But the artist’s journey rewards—through his negotiation with locals and official hurdles encountered (he was left alone after saying it was an ad campaign)—defamiliarizing the logistics of a modern convenience that modern tourism expects, and shedding light on stark gaps in wealth.

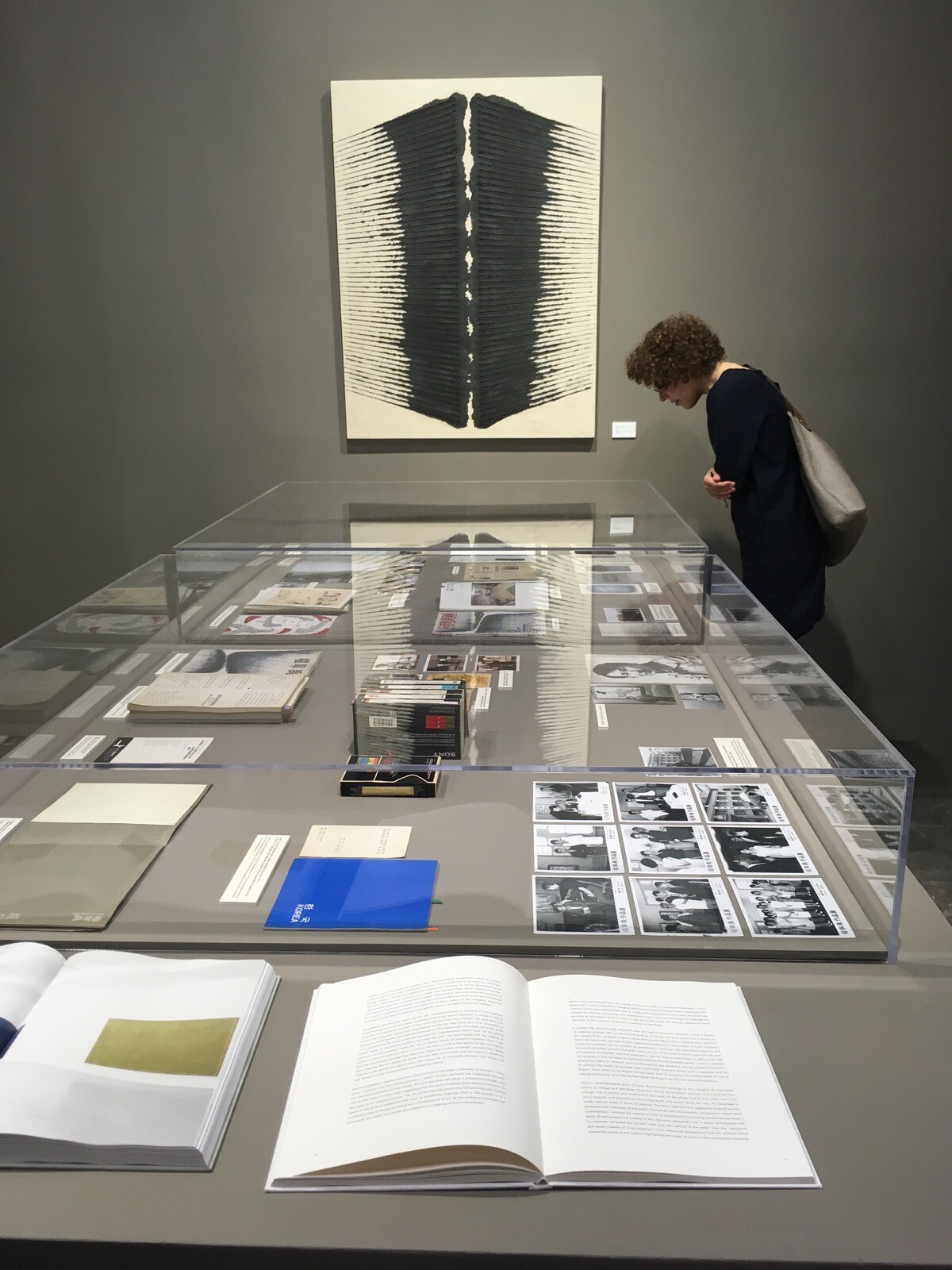

At Galerie Rüdiger Schöttle, Munich, Goshka Macuga exhibits a configuration of busts of the world’s scientists, politicians, and thinkers (including Karl Marx, 2016), part of her imagination of a post-human world. At Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne, Cao Yu’s protrusions and recesses, on the canvas (as in Mother no. 4, 2016) and with a moving sex toy under a blanket (Mount Fuji no. 1, 2017), evoke symbolic representations of gender with a deft touch and humor. In a fair that enables plenty of regional and international encounters, even the more historical representations of works from disparate art histories can be highly rewarding, if a bit didactic. The Kabinett section excels in this respect, with Seoul’s Kukje Gallery presenting the Dansaekhwa artist Kwon Young-woo along with a range of contextualizing archival materials—magazines and exhibition catalogues—from the period. At Gmurzynska, Zurich, viewers can see some early works by Christo (such as Red Package, 1968), everyday objects wrapped in polyethylene which anticipated his larger projects of wrapping trees, islands, and architectural structures (this is in fact the first time Christo’s work has been presented in Hong Kong). Keiichi Tanaami’s hallucinogenic video animations at Nanzuka, Tokyo, commingle 1970s Japanese Pop sensibility with erotic imagery and the artist’s own experiences of hallucinations from suffering through bombing raids during World War II.

Outside the exhibition hall, the VR project at Asia Art Archive’s booth, produced by Emblematic Group founder, the “grandmother of virtual reality” Nonny de la Peña, exceeded expectations. Viewers (or players?) re-enact Lin Yilin’s classic performance Safely Maneuvering across Lin He Road (1995), in which originally the artist had moved a wall, brick by brick, across the road in Guangzhou, northwest of Hong Kong. This activation of archival material in a first-person, VR format opens up fruitful possibilities and echoes the broader popularity of VR, whether in gaming or in art. Perhaps to the constructions of self-image through selfies we can now add the first-person-view engagement with the digital (one thinks of Snapchat Spectacles, too). Virtual reality can be world-makingly immersive, or else claustrophobic and yet devastatingly alienating in its loneliness. Given the disastrous consequences of fake news and filter bubbles, it’s hard not to take fright at the thought of what new alternate realities and truths will be conjured up.