Religion, magic, art, physics, and mathematics blend in Goutam Ghosh’s solo exhibition “Morph, blend and flatten (space) of Bird, Reptiles and Flower.” The delicate, sometimes dreamlike paintings gain energy from the friction between ideas from different disciplines and systems of thought as they come into contact. Ghosh draws on conversations with Indian scholar Kaustubh Das about tantra and its understanding of consciousness as a source for both his thinking and making. “Tantra,” Sanskrit for loom, weaves together complex concepts and practices. In the tradition of sacred art, tantra drawings and paintings of abstract geometric shapes were used as meditative tools to awaken heightened states of embodied consciousness. Tantra is of interest to Ghosh because it is a phenomenological tradition that…

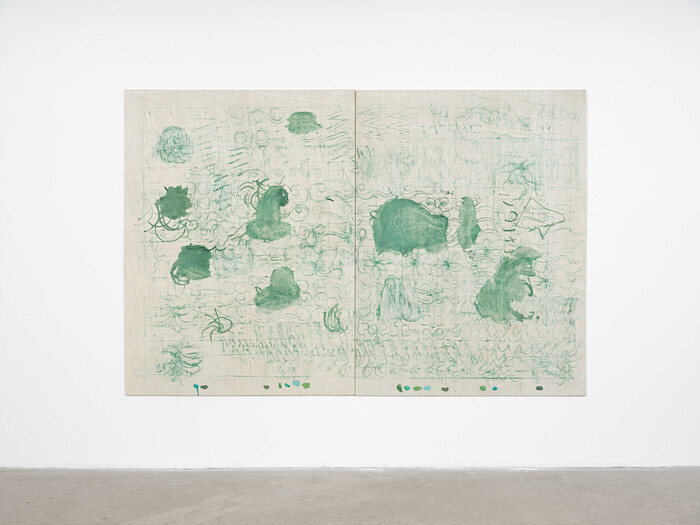

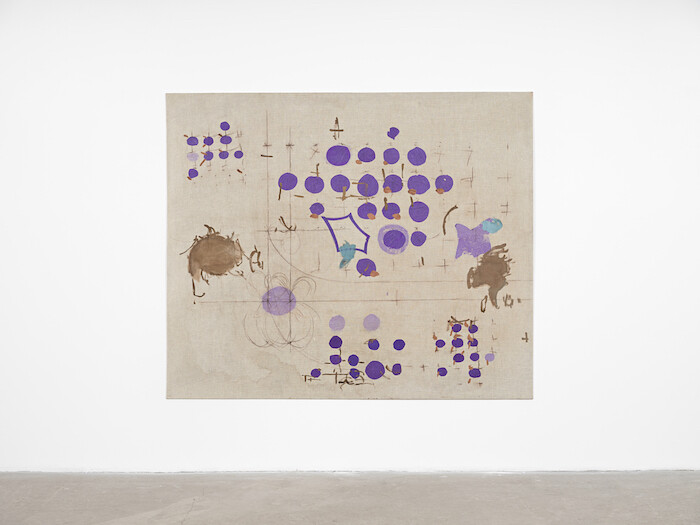

“Morph, blend and flatten (space) of Bird, Reptiles and Flower,” Goutam Ghosh’s solo exhibition at STANDARD (OSLO), is elaborated in the gap between drawing and language. In Violet (all works 2018), for example: rows of luminous parrots line the margins of a purple field, like awkward hieroglyphic signs. Ghosh has overwritten them with a quick hand in brown ink, as though he wanted to touch them in some space beyond their symbolism; as though he could scratch open the symbolic universe they circulate within.

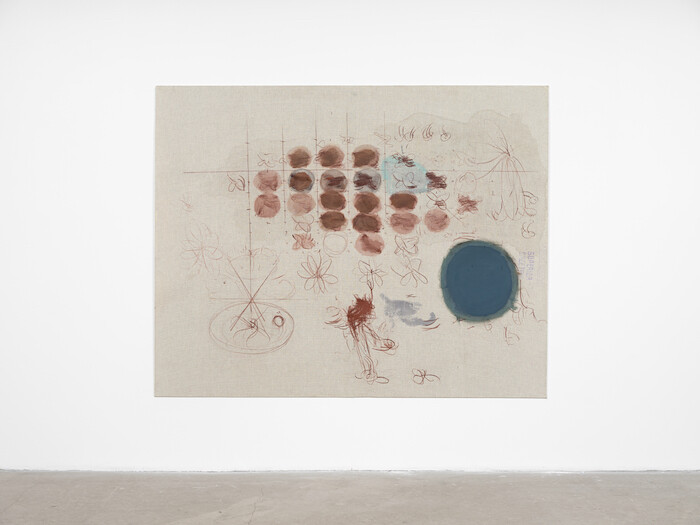

Glycerin is a large painting on plywood, but the circles plotted against a sketched grid are impressions of kite paper—an inexpensive yet lustrously colored paper sold in thin sheets at corner stores throughout India—the color of which Ghosh has transferred to the work’s surface, staining it…

Religion, magic, art, physics, and mathematics blend in Goutam Ghosh’s solo exhibition “Morph, blend and flatten (space) of Bird, Reptiles and Flower.” The delicate, sometimes dreamlike paintings gain energy from the friction between ideas from different disciplines and systems of thought as they come into contact. Ghosh draws on conversations with Indian scholar Kaustubh Das about tantra and its understanding of consciousness as a source for both his thinking and making. “Tantra,” Sanskrit for loom, weaves together complex concepts and practices. In the tradition of sacred art, tantra drawings and paintings of abstract geometric shapes were used as meditative tools to awaken heightened states of embodied consciousness. Tantra is of interest to Ghosh because it is a phenomenological tradition that validates knowledge resulting from direct experience which would be difficult to empirically account for, like the movement of energy or time. Yet, his paintings also show an awareness of the human process of cognition and its reliance on quantifiable data or pattern. The mind wants to recognize and categorize, to find a pattern.

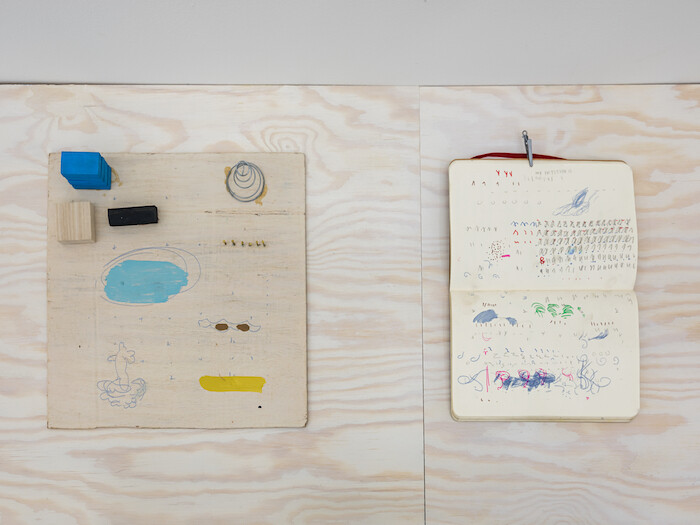

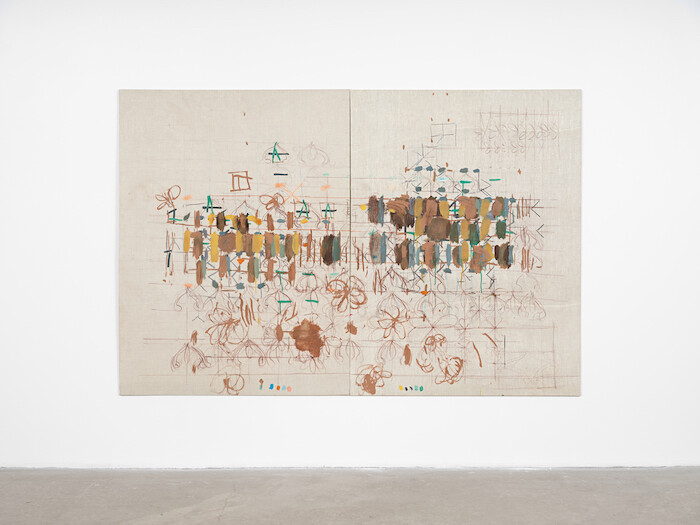

Paintings like Untitled (all works 2018), Glycerin, and Tennis Ball exhibit a subjective pattern, while they bring up references to systems of order and logic. All three paintings have a grid structure, through which objects move like musical notations. In Untitled, earth-toned flowers and colorful brushstrokes appear in circular motion, while Tennis Ball suggests some sort of schematic organization of evolving organic material in an uncertain relationship to the large blue circle from which the work derives its title. As is the case with many of Ghosh’s paintings, the painted objects seem bound or conjured by a logic viewers are not expected to decipher. A work like Trick in the tent, made up of white and red circular abstract scribbles on a black board, yields its dynamic composition exactly from this feeling that the formula is present but inaccessible. In another painting, Violet, Ghosh leaves a large purple field of color untouched, as an open suggestion of space for other possible scenarios for objects—in this case, parrots and an apple—and paint to come together. A table display running the length of one wall of the gallery includes small assemblages and the artist’s sketchbooks filled with drawings and personal notes on materials like mercury. Together they exemplify Ghosh’s interest in object ontology, and how objects might collapse or transform their state.

Mercury, and its material properties, is also the inspiration for the title of the film PAARA, made in collaboration with Oslo-based artist Jason Havneraas, here presented as a double projection behind a plywood partition. According to the artist, the title plays both on the Hindi word for mercury, paraa, as well as two confluent Sanskrit catergories “Para Vidya,” transcendental knowledge “and “Apara Vidya,” material knowledge.

The film’s narration explores the memories of a 90-year-old magician. “It was a grand day for a grand narrative. A space necessarily opened up with 360 degrees of possibility,” chants the narrator, as performers wearing colorful, pointed hats and geometric Dada-like costumes position themselves in various constellations along white stage markings, outlined on the ground. They hold and move various props, but the relationship between the bodies and performed rituals is elusive; the rules of the game remain unknown to us. In the gap between the narrator’s words and the performed magic rituals, objects both exist in time and carry it forward, always between a moment of stasis and of becoming something else. Just as the magician in the film recollects how he moved a rope to make people believe they were seeing a snake, so objects in Ghosh’s universe freeze momentarily into a specific state to become a part of a composition.

As a whole, the exhibition keeps returning us to the idea of the pattern as a structure that enables both mind and objects to wander between academic disciplines and spark new states of being. In Ghosh’s practice, the pattern allows for opposing knowledge systems to co-exist, while he carves a space both in making and meaning for subjective experience of that which lies beyond the limits of the frame.

“Morph, blend and flatten (space) of Bird, Reptiles and Flower,” Goutam Ghosh’s solo exhibition at STANDARD (OSLO), is elaborated in the gap between drawing and language. In Violet (all works 2018), for example: rows of luminous parrots line the margins of a purple field, like awkward hieroglyphic signs. Ghosh has overwritten them with a quick hand in brown ink, as though he wanted to touch them in some space beyond their symbolism; as though he could scratch open the symbolic universe they circulate within.

Glycerin is a large painting on plywood, but the circles plotted against a sketched grid are impressions of kite paper—an inexpensive yet lustrously colored paper sold in thin sheets at corner stores throughout India—the color of which Ghosh has transferred to the work’s surface, staining it the same buoyant purple as in Violet. The birds are both symbolic and indexical, figures in the exhibition’s language and also the intimate stains of another surface. In this doubleness, each volume of transferred color represents the impossible ground on which a sign depends for sense.

The press release, which Ghosh wrote himself, is a sketch in language of the dividing line between two terms that operate as different states of being: “does reflection become shadow later?” With the idea of “later,” the artist is also playing on the instability of grammar as a temporal container for each word it implicates. He is working against the idea that a tense is designed to fix a form in time, even if only in the conditional; for example: “If there were a kite, it would have been purple.”

But what tense to use for reflections of color and language on wood and landscape? Where are such phenomena in time and space? What of “things, those that disappear in the process of becoming,” things destroyed by the effort of transferring their color and their reference to child’s play to a more immutable surface? The answer Ghosh gives in the press release—that such things become flowers—could be read as flippant were it not for his choice of color: aquamarine, rust, a thick, almost dirty yellow, bright teal, and brown that appear drawn from the earthen landscape of the film playing in the back of the gallery. There is an acknowledgement, in color, that flowers die very quickly.

PAARA, shown in two loops, is a film shot on 16mm and then digitized, made in collaboration with artist Jason Havneraas. Seven minutes into a 35-minute loop, two men wearing paper hats, one on the bank and the another in the middle of a muddy, shallow pond, shuttle a slender piece of wood between them, balloons balanced on either end. They are patient, the air is still. Another body, also wearing a paper hat, suddenly appears between them in the shot, breaking their balanced movement. The narrator’s voice intones: “When Myanther was a child, he caught a fish, and cut it open. For the first time, he separated organs from a life form, finding something like a balloon…” The narrative reflects the drawing in space that is captured on film, which it repeats with a difference.

Each scene in the film is structurally analogous: there is a task, there are people—people who are also somehow luminous drawings—and there is a spoken narrative overwriting their gestures that is concise without being analytical. It does not state the intention behind the system that governs the appearance of these people in the world. It reflects on them.

In the works on view—the paintings and PAARA, but also in a series of quasi-architectural models and sketchbooks placed on a shelf that lines one wall of the exhibition—Ghosh is studying the experience of a form that is not stable. The grid is there, the graphic sign is dutifully transcribed and transcribed again, and the task set forth by the forms Ghosh sketches in space with plywood and paper is attended to, every time. Despite this diligence, I leave his exhibition marked by the possibility that meaning is translucent. It strikes me that there are entire universes of sense that elude the sign, the form, and the drawing altogether, the reflections of which we call shadows in order to disavow the inadequacy of language.