When “Bodies of Water,” the 13th edition of the Shanghai Biennale, opened in November last year, it adopted a fluid approach to programming in response to the pandemic. In place of the traditional biennale format was a multi-platform “in crescendo” project comprising three “phases” and lasting a total of eight months. The first two of these, “A Wet-Run Rehearsal” and “An Ecosystem of Alliance,” featured live events, screenings, and discussions—held within the Power Station of Art (PSA), in art spaces along the Yangtze river, and online—that explored the exhibition’s central concerns: ecology, hydrology, posthumanism, and the interconnectedness of all lifeforms on earth. In the midst of a pandemic precipitated by zoonosis, these are timely concerns.

In April this year “The Exhibition,” the biennale’s third and final phase, opened in the PSA. This massive decommissioned power station, modelled on London’s Tate Modern, was in 2012 repurposed as the first state-run museum of contemporary art on mainland China. Situated on the banks of the Huangpu River, which the electric plant helped to industrialize, it is an apt location for an exhibition that emphasizes the inseparability of humans from the natural world they exploit. Curated by architect, researcher, and writer Andrés Jaque alongside a curatorial team comprising Marina Otero Verzier, Lucia Pietroiusti, Filipa Ramos, and Mi You, “Bodies of Water” takes as given “the way art constitutes and infiltrates life itself.”1 As a whole, the works selected for this exhibition reach for new forms of collectivity and interdependence between species.

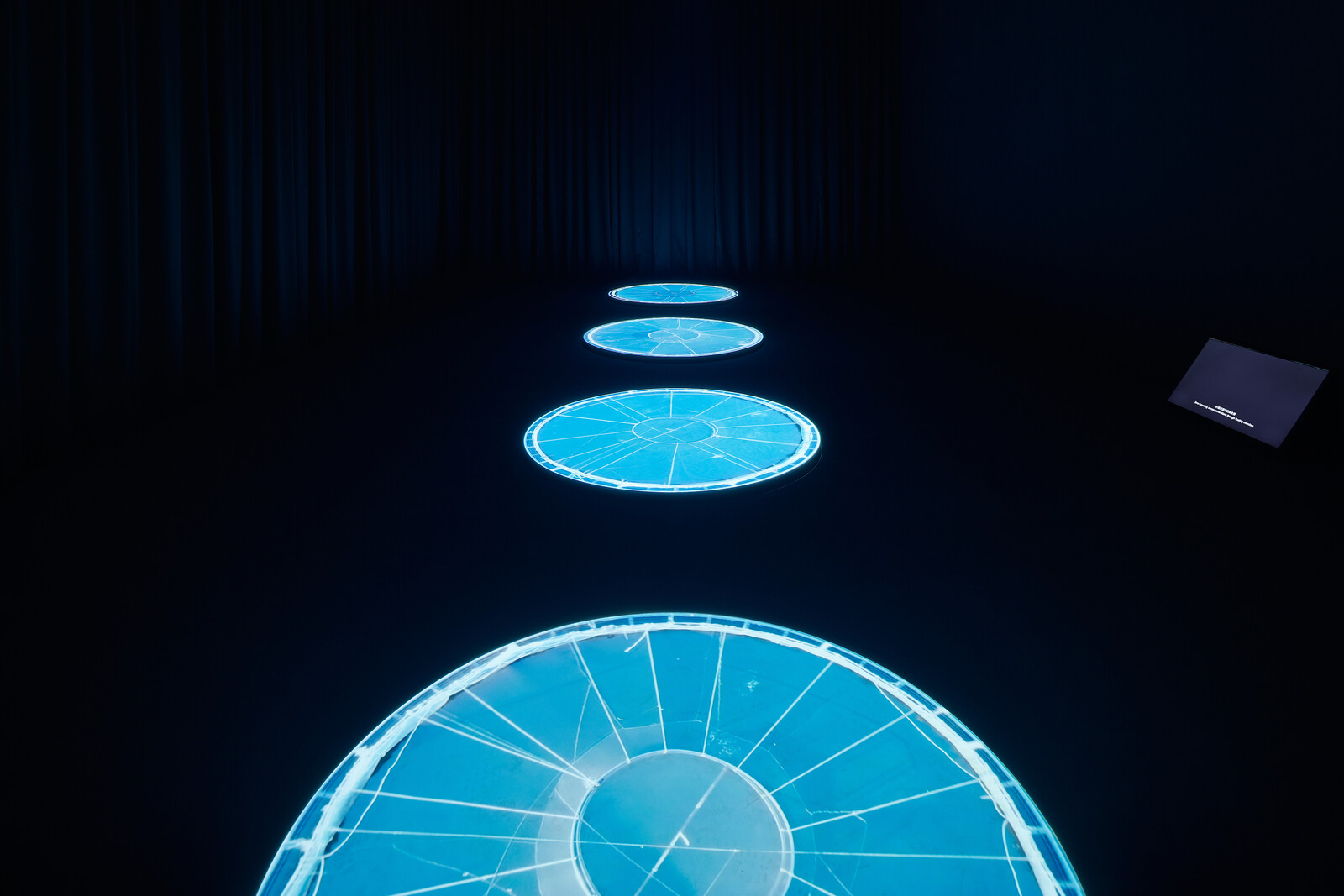

The tone is set by Michael Wang’s 10,000 li, 100 billion kilowatt-hours (2021), a terrarium housed in a glass-and-steel box resembling a shipping container dropped into the center of Shanghai. Windows set into its side reveal a scale recreation of mountains in the province of Qinghai, whose glaciers are the source of the Yangtze River. Water taken from this river—which supplies Shanghai’s taps and the Three Gorges Dam power plant, which in turn supplies electricity to the city—is blown through vaporized jets into refrigerated air cold enough to freeze it, from which it falls onto the modeled mountains as snow. On the PSA’s ground floor are several installations which extend these connections between humans and bodies of water. Cao Minghao and Chen Jianjun’s 2018 installation Water System Museum—part of an ongoing project begun in 2015 that looks into the Dujiangyan irrigation system, a third-century flood control system on the Min River, a Yangtze tributary—features vitrines, photographs, videos, archival maps, and a reconstructed ferry boat suspended from the ceiling. This thoughtfully installed archive reveals the inextricable connections between the personal, natural, and ideological aspects of China’s long history of co-existence with, and dependence on, water.

The number of moving-image works on the upper floors of the PSA—set amidst drawings by Joan Jonas, Heather Phillipson’s pink-hued, bedroom-sized installation of sketches of rats set to music (Music for Rats, 2021), and paintings by Cecilia Vicuña (notably Almagria, 1971/2021), among other works—is striking. Like the exhibition format itself, this may be a response to the logistical intricacies of mounting a biennale in the midst of a pandemic, but it also feels appropriate to the circumstances. As Jennifer Fay points out in Inhospitable World: Cinema in the Time of the Anthropocene (2018), “the Anthropocene puts an end to any separation of natural history from human history, and if there is any representational medium that best captures natural environments made human, it is film.” Many of the videos and films showcased in this exhibition draw attention the inseparability of the natural and the human spheres, emphasizing both the sensual experience of human-built infrastructures and the nonhuman intelligence that thrives in natural ecosystems.

Liu Chuang’s documentary Can Sound Be Currency? (2021) is one example among many. Commissioned for the biennale, and forming the second part of his 2018 project Bitcoin Mining and Field Recordings of Ethnic Minorities, this documentary examines the ecological costs of mining digital currencies in remote, mountainous regions of Western China, in which a high number of hydroelectric power stations are situated. These mountainous areas are also home to diverse minorities, which feature in the film, and who have maintained a tense relationship with the state government. By contextualizing questions of capitalization within the histories of science and culture, Chuang draws speculative connections between western modernity and Chinese traditions to remind the viewer that the most advanced technology is dependent on local ecologies and intelligences.

A single-channel video work by Vera Frenkel, ONCE NEAR WATER: Notes from the Scaffolding Archive (2008–09), is an architectural vision based on scientific speculations. Combining fiction and documentary, the video’s overlapping layers of text, sound, and footage from an archive of footage of construction sites and scaffolding conjure a vision of a city as a self-sustaining, posthuman organism. Tracing the poetic in the social, the video exposes the grief that a city can experience when architectural opportunism deprives citizens of visual and physical access to water.

Bodily fluids, which exceed the boundaries of bodies and offer points of connection between organisms, operate throughout this exhibition as metaphors for forms of co-existence that extend beyond dominant socio-political narratives. As such, the biennale conceives of diverse bodies of water connected by the search for a planetary, all-encompassing “fluid solidarity.” Yet the question of how such “wet-togetherness” might look in the current global situation—one characterized by increasing geopolitical tensions and growing nationalist movements—is left unanswered by this stimulating exhibition.

https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/386291/13th-shanghai-biennalebodies-of-water/.