Ella Sheppard Moore’s father bought her freedom from enslavement as a child; as the lead arranger and composer of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, she grew up to establish Negro spirituals (or plantation songs) in the landscape of American popular culture. Listening to a 1909 recording of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which happens to be my favorite spiritual, I hear a haunting ringing out as the four members sing the phrase “coming for to carry me home”—taking a hold of the word “home,” stretching it, and drawing it out over a run of four notes wherein the register lowers twice as the chorus loops back around.1 What is utterly magnificent about this rendition of the song, which differs greatly from the version I grew up listening to and singing, is…

In the year prior to his untimely death in March 2019, Okwui Enwezor was developing an exhibition to coincide with the 2020 presidential election that would examine “the crystallization of black grief, in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance.”1 That his vision—realized by a curatorial team including Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Lignon, and Mark Nash—feels so pertinent today is a sobering reflection on both the American status quo and the magnitude of the loss of Enwezor’s voice.

The immersive aural experience of “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” is haunting; immediately on entering the exhibition, the viewer is enveloped by a soundscape that continues to reverberate long after leaving…

Ella Sheppard Moore’s father bought her freedom from enslavement as a child; as the lead arranger and composer of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, she grew up to establish Negro spirituals (or plantation songs) in the landscape of American popular culture. Listening to a 1909 recording of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” which happens to be my favorite spiritual, I hear a haunting ringing out as the four members sing the phrase “coming for to carry me home”—taking a hold of the word “home,” stretching it, and drawing it out over a run of four notes wherein the register lowers twice as the chorus loops back around.1 What is utterly magnificent about this rendition of the song, which differs greatly from the version I grew up listening to and singing, is that it conveys a deeper, reifying story of radical refusal, stirring the condition that emerges from living in pursuit of freedom from the imagination of white terror. This kind of living is marked in the formations of early Black American music, wherein songs are in part prayers and prophetic visioning. They are spiritual speech acts that map pathways for new possibilities, self-possessed futurities.

Okwui Enwezor wrote that the social space and production of Black music history is “part of the unique encounter between white power and black bodies.”2 In that recording of “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” lies the sonic heritage and resonance of Black mourning and grief, expressions of which are reflected in Enwezor’s posthumously realized “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America.” The show exemplifies the role of the voice, the strategies of both song and speech, as powerful sites of sorrow and recovery. The independent and experimental agency of Black sonics today is illustrated by a number of projects in the exhibition, which position the voice as a location where individuals or the collective can act and be in action, or activate the social dialogues of discovery, destruction, and revision.

On the second floor, the installation Manifestos 3 (2018) by Charles Gaines fills a room with a composition that rings from mounted speakers placed next to drawings of sheet music and a video piece that features scrolling text. The transformation of text into a musical score presents two audio pieces that speak to the travails of art, culture, and homeland, setting James Baldwin’s 1951 essay “Princes and Powers” alongside Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1967 acceptance speech at the UK’s Newcastle University, which highlights the “inescapable network of mutuality” that binds the races together.3 The interaction between discordant chords and political speech acts creates a complex pulse and unsteady tune, formed in response to words like “colonized,” “racism,” “capitalism,” “labor,” “determination,” and “power.”

Belting from the neighboring room are melodic tonal expressions from singer and songwriter Alice Smith, part of a video piece by Kahlil Joseph entitled Alice™ (you don’t have to think about it) (2016). Filming up close, Joseph captures Smith’s drifting visage during a recording session colored by the artists’ shared recent experience of bereavement. Fragments of lyrics lace throughout the piece —“don’t wanna think about it… don’t even wanna try.” The Black Monks of Mississippi deliver a reckoning in Theaster Gates’s video work Gone are the Days of Shelter and Martyr (2014). The performance by vocalist YAW is a call-and-response to the throwing of an unhinged door in an abandoned church in the South Side of Chicago. I saw an installation of this piece at the Venice Biennale curated by Enwezor in 2015. The pitch black of the room, alongside the chalky smell of dust, rusted metals, and scraps of concrete from the remnants of the now-demolished church, left a stinging impression on me. YAW’s textured wails that encircle the lyrics of “I been working… working away […] I been working in the field… for a long time” make me think of the deep time embedded in Black prayer and blues, a concept that is also documented in diptych portraits by Dawoud Bey. This series, “The Birmingham Projct” (2012), registers the deep time of racial terror by exploring the violence surrounding the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist church in Birmingham, and that persists today.

In recalling the work of jazz composer Roscoe Mitchell, Enwezor wrote of the meta-spaces that also exist within radical musical traditions: “the emancipatory possibilities of the sonic […] stimulated the sense of an open field, crafting all sorts of meta-spaces of discovery for how black experimental music articulates new kinds of locations for individual and collective freedoms.”4 The idea that a sonic piece can present new spaces of discovery is embodied in the sharp and percussive structures of Tyshawn Sorey’s Pillars (2018). The polyrhythms of this work combined with Smith’s groaning, which spills into the room, pulled me to the edge of a melancholic release. It recalled my experience of Garrett Bradley’s short film Alone (2017) in the lobby of the museum: a soft sadness coupled with a profound knowing, a descent into the interior. The exhibition addresses poetic responses to acts of commemoration, labor, grief, and reclamation. It reminded me of a recurring dream I have that Black folks can fly, and are hunted for it. There is no sound. Only the high speed of silent jubilation.

Although no recordings remain of the original Jubilee singers, some of Moore’s sheet music and the recordings of the first Fisk Jubilee Quartet from 1909 are preserved.

Quoted in Adrienne Edwards, Jason Moran (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2018). 99.

Martin Luther King, Jr., “Speech on Receipt of Honorary Doctorate in Civil Law,” November 13, 1967.

Quoted in Adrienne Edwards, Jason Moran (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2018). 99.

In the year prior to his untimely death in March 2019, Okwui Enwezor was developing an exhibition to coincide with the 2020 presidential election that would examine “the crystallization of black grief, in the face of a politically orchestrated white grievance.”1 That his vision—realized by a curatorial team including Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Lignon, and Mark Nash—feels so pertinent today is a sobering reflection on both the American status quo and the magnitude of the loss of Enwezor’s voice.

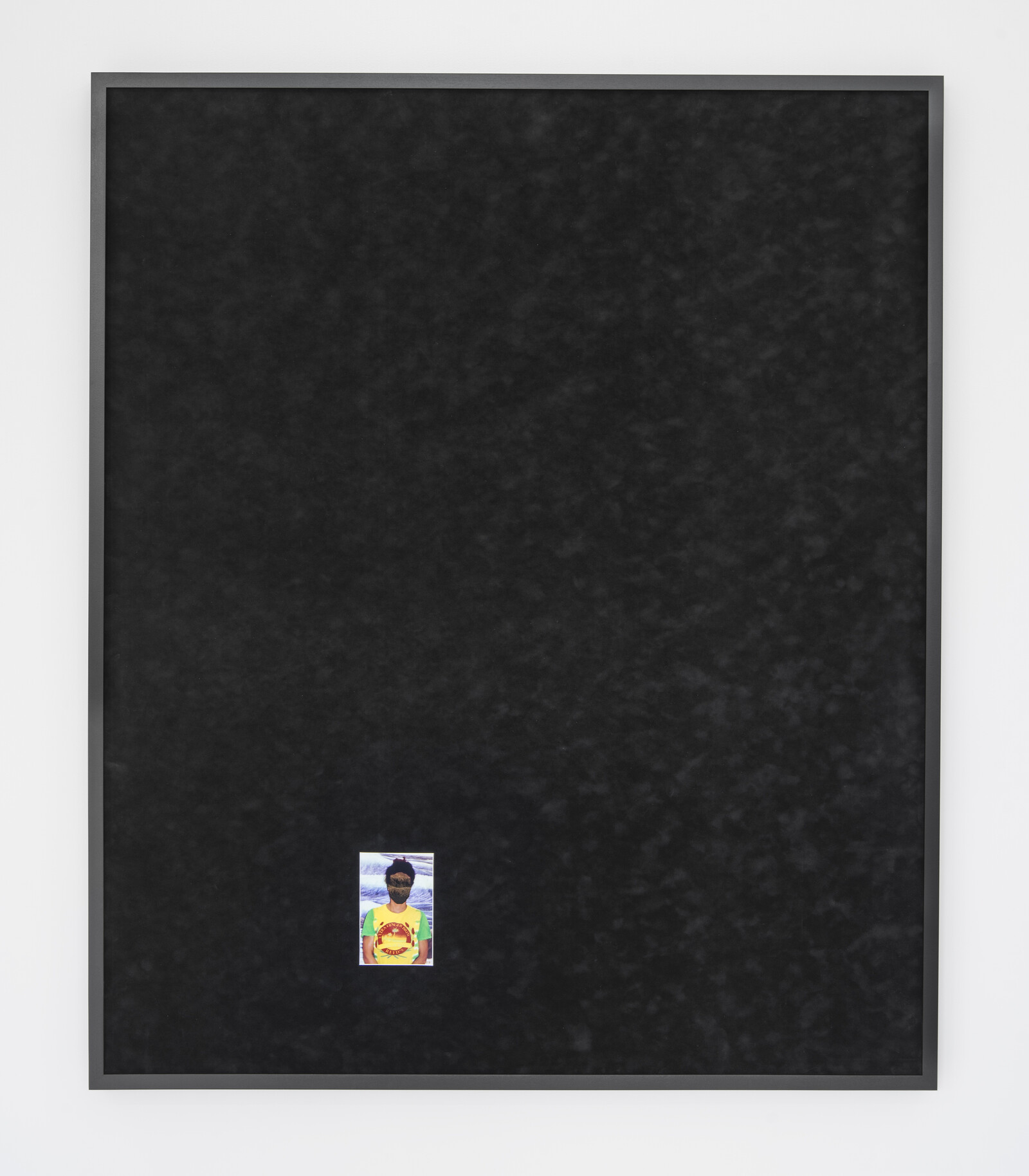

The immersive aural experience of “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” is haunting; immediately on entering the exhibition, the viewer is enveloped by a soundscape that continues to reverberate long after leaving it. The effect begins with Rashid Johnson’s Antoine’s Organ (2016), a towering ecosystem built around black steel scaffolding that houses an upright piano nestled among plants, its various elements emitting layers of sound to produce a captivating cacophony. Enwezor’s curatorial practice placed a longstanding emphasis on the sonic, and several pieces here involve musical compositions and performances: Charles Gaines’ Manifestos 3 (2018), Tyshawn Sorey’s Pillars (2018), and Theaster Gates’ Gone are the Days of Shelter and Martyr (2014).

As the viewer descends from the fourth floor to the third, they are confronted with a series of sculptural works, each forming an inventory of a long history of racial violence in the US. How to capture this ever-present violence preoccupies many of the artists in “Grief and Grievance.” Only after reaching the bottom of the narrow staircase, and gazing back at the banners hanging from the ceiling, can visitors take in Hank Willis Thomas’s 14,719 (2018) in its entirety, and assimilate its reference. The crisp navy-blue banners, stitched with rows of white stars, flawless and precise, recall and repurpose the American flag, each star memorializing someone shot and killed in America in 2018.

Each of Melvin Edwards’s small-scale wall reliefs, welded together from steel objects—locks, chains, nails, shovels, and horseshoes—is a cold, quiet narrative of the way life and labor are fused together through violence. Part of “Lynch Fragments,” a series he began in 1963, the sculptures hang at eye level, challenging the viewer to imagine the violent uses to which even everyday materials can be put. Diamond Stingily brings mundane objects from her childhood in Chicago’s West Side into the museum, commemorating Black cultural memory while questioning what belongs in the space. Here, three apartment doors from the series “Entryways” (2016, 2019) are lined up against a wall, each with a baseball bat propped up against it, as her grandmother used to do. While gesturing to the violence that shadowed her childhood community, Stingily also acknowledges the resilience of matriarchs who protect their domestic spaces.

The particular challenges faced by Black women are highlighted throughout the exhibition. In a selection from The Notion of Family (2001–14), Latoya Ruby Frazier uses the medium of social documentary photography to capture the marginalized stories of her hometown of Braddock, PA. The home of one of the country’s first steel mills, the town has suffered the same fate as many in post-industrial America; unemployment, white flight, divestment of resources and infrastructure. Frazier’s photographs center on the women in her family; through a series of portraits of herself, her mother, and her grandmother, she uses the camera as a weapon through which they assert agency. They are not only subjects, but also the authors and producers of the narrative, facing the camera head-on, defiant and unflinching. Garrett Bradley’s documentary short Alone (2017), engages with similar textures of intimacy as it follows Aloné Watts in her struggle to answer the question: “What would it mean to marry someone behind bars?” Voiceovers by Watts and her fiancé accompany footage of a daily life shaped by the violence of the prison-industrial complex, a system aptly compared to slavery in intent and design.

Several artists here employ the documentary qualities of black-and-white photography to stage their own restorative archives in projects that seek to bring the marginalized to the center of the frame, while challenging the traditional format of portraiture. In a series of diptychs, Dawoud Bey’s “The Birmingham Project” (2012) combines a portrait of a child (the age of one of the four victims of the bombings at the 6th Street Baptist Church on 15 September 1963, and of the two other linked attacks in the city that day) with one of an adult, 50 years older (the age that child would be now, had they survived). Likewise, in her series “Constructing History” (2008), Carrie Mae Weems claims authorial power by reimagining and restaging momentous events such as The Assassination of Medgar, Martin, Malcolm or The Capture of Angela. These works express the urgent need for commemoration, for remembering and recognizing one’s own history on one’s own terms.

Above all else, “Grief and Grievance” is an insistence that Black grief, like Black life, is as varied, multifaceted, and generative as it is profoundly painful. No piece better encapsulates this spectrum of experience than Arthur Jafa’s Love Is The Message, The Message Is Death (2016), with its fast-paced collage of protests, sporting events, music performances, street life, and police brutality set to Kanye West’s gospel-inflected “Ultralight Beam” (2016). The accumulation of scenes across a broad emotional register is both exhilarating and exhausting. Like many of the works in this exhibition, Jafa’s seven-minute montage is by now something of a classic. It is testament to Enwezor’s dedication to amplifying the work of Black artists that many of these names will already be familiar to their audience; the intergenerational dialogue between the 37 participants in “Grief and Grievance” allows for an act of collective mourning, celebration, and commemoration in the face of a national emergency.

Okwui Enwezor, introduction to Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America (New York: Phaidon/New Museum, 2021), 7.