The Walter De Maria exhibition at the Menil has everything: guns (HARD CORE, a film from 1969, shows Michael Heizer and an actor dueling in the desert), swearing (“Color, Size, Shape, Shit” is number 25 on the list of One Hundred Activities, a score work from 1961), and even the faint possibility of a romantic encounter in the form of a pink mattress and a pair of headphones playing seductive and relaxing field recordings of the Atlantic’s steady breath (Ocean Bed, 1969).

“Boxes for Meaningless Work” does not, of course, contain De Maria’s most iconic pieces—The Lightning Field and New York Earth Room (both 1977). But the show is rich enough to serve as a solemn reminder of what passed as artistic expression in the golden years of American Imperialism, when it was still possible for Minimalists to repackage the formal purity that had denoted universal social progress for Russians and Germans in the 1920s. It is interesting to look at the sea change in relationships between the avant-garde and infrastructure over this period. If the Soviet artist would overreach towards a platonic ideal of a sexless, classless, and ageless society, an approach best exemplified by El Lissitzky’s About Two Squares (1922), a Minimalist piece resembles a doodle on the margins of the great history of North American retail.

De Maria’s work feels defeatist, and while he never officially articulated the mood behind the pieces, one could use Donald Judd’s 1981 article on the historical avant-garde for reference, wherein he writes of feeling “swamped by a large public to whom art is just phenomena” and of a sense that in “the thirty-sixth year of the American Empire the public is not so different from the Russian public that ignored those artists.” The only difference, for Judd, is that “The Central Government, though, instead of scowling like Lenin, smiles, since art makes jobs, and helping art is a cheap way to look good.”1 So much for the future.

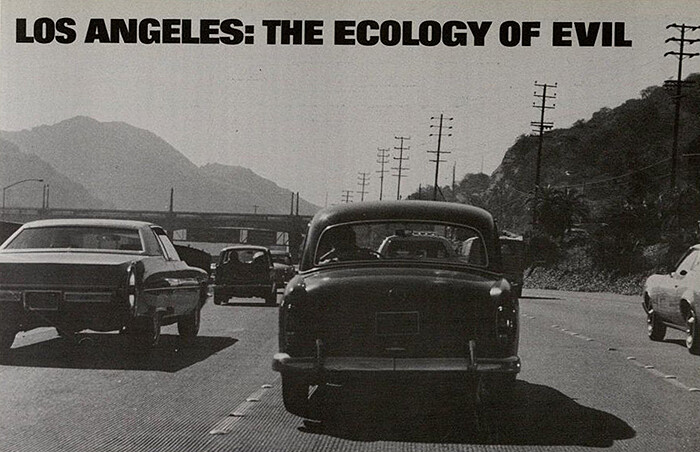

Of course, criticizing De Maria and his comrades can look like flogging a dead horse. Still, it serves as a perfect measure of distance between its moment and the now. It’s striking to consider De Maria’s work after Occupy, after #MeToo, after the curatorial starships have moved to decolonize the exhibition space. In De Maria’s time there was no shortage of art addressed to social ills, but it now seems impossible to imagine that a purist geometry could cut across it all. An encounter with De Maria’s art casts a shadow of hopelessness. It’s like drifting through an abandoned mall, in which every shabby storefront reminds you of the goods that once were. The works can, indeed, be described as “meticulously planned and brightly enclosed structures … ideas conveniently located just off the great American highway.”2

The quote is from William Severini Kowinski’s The Malling of America (1985) and, once you see the connections between De Maria’s oeuvre and the rise of the American shopping mall, you cannot unsee them. This offers a truly materialistic perspective on both his work and on Minimalism in general. You start noticing how much of De Maria’s work is related to consumer culture, with early absurdist lists of “instructions” directing the viewer to the store, the coffeeshop, the white shoes of a person in a subway station, and so on (One Hundred Activities, 1960-61). It might be critique, but at this level of abstraction, the intention doesn’t matter. The Minimalists had successfully created an art that did not contain new insights, but instead made you desperately want them, because the packaging looked so appealing.

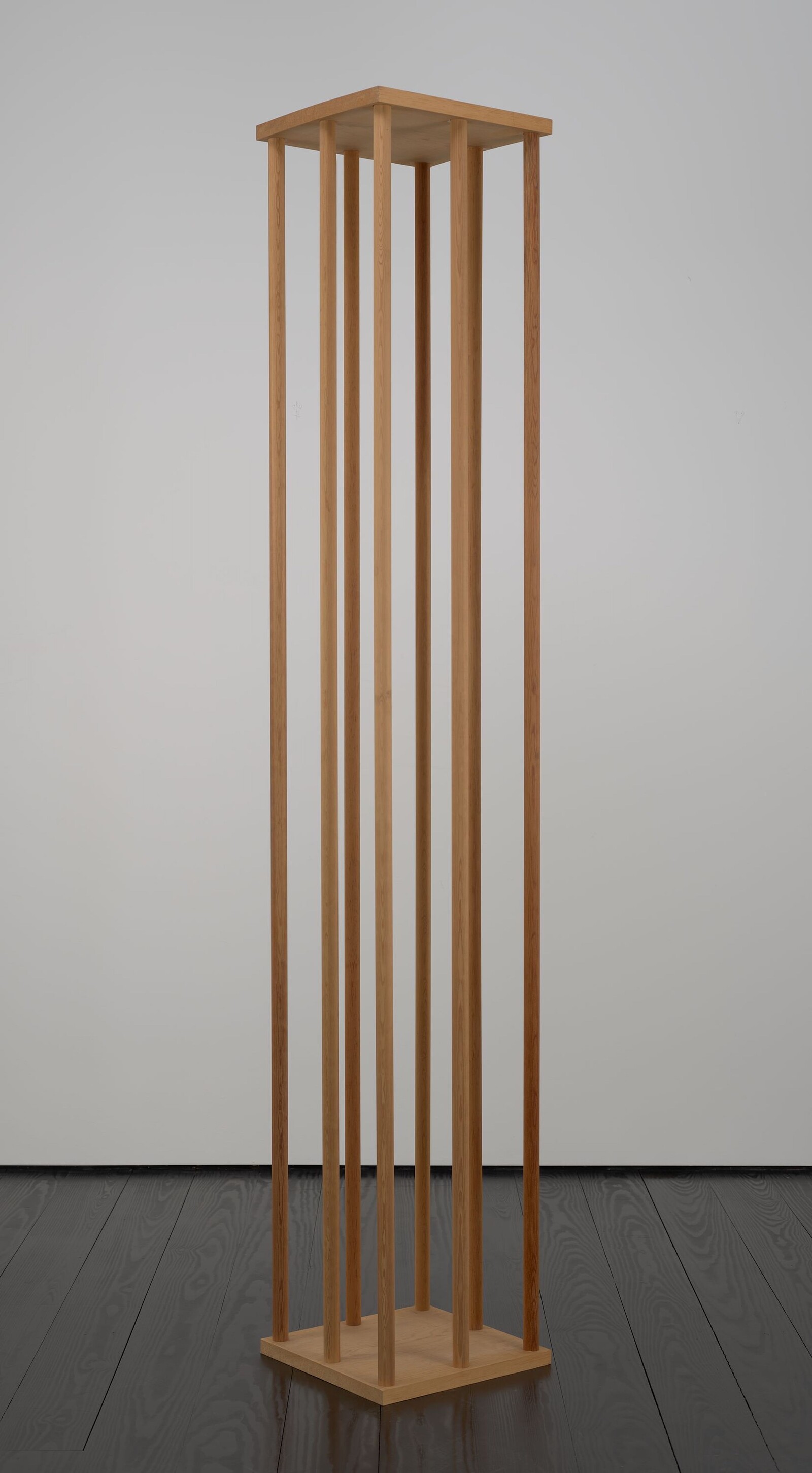

In De Maria’s case, one has trouble remembering why we wanted these insights so badly in the first place. Oh, we might say, looking at a sculptural portrait of John Cage in the form of a human-sized wooden cage (Statue of John Cage, 1961): this is a riff on the vacuous, Zen subjectivity of the postwar avant-garde. Problem is, the acquisition by Western museums of more art from Japan and South Korea—Mono-ha paintings, documents of Gutai performances—has provided their audiences with more direct and informed engagements with these philosophical concepts. If, to draw out the consumerist metaphor a little further, the meaning of a given work is a combination of the package (form) and the good (potential insight), then Walter De Maria’s pieces are past due. This is no fault of the curator, Michelle White, who does an admirable job of introducing a human, endearingly amateur dimension to the artist by including lots of early work inspired by Fluxus. But no matter the humorous intention, even the lighthearted pieces feel wrong.

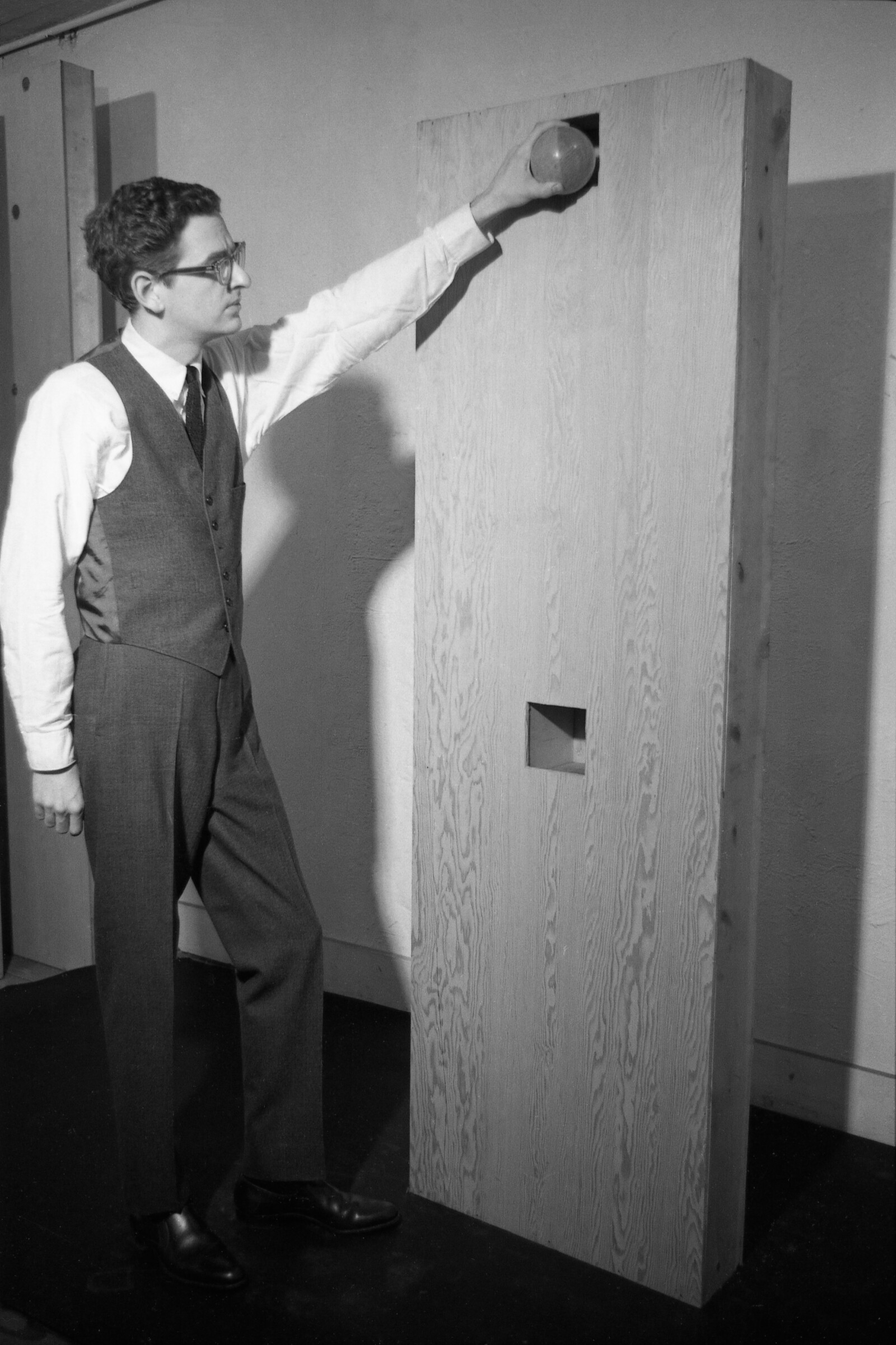

Boxes for Meaningless Work (1960/61), for instance, are painted instructions for manipulating the titular wooden objects to “make you feel and think about yourself, the outside world, morality, reality, unconsciousness, nature, history, time, philosophy, nothing at all, politics, etc., without the limitations of the old art forms,” as the artist is quoted in the exhibition booklet. Even if the ambition reaches far beyond the capacity of the pieces to achieve, they inspire thoughts contrary to the artist’s intention. Does “meaningless work” really exist? And if so, isn’t it closer to the ritual activities of retail consumerism: the processes of boxing, delivering, commuting, and not, as De Maria would like us to believe, the Zen of empty gesture?

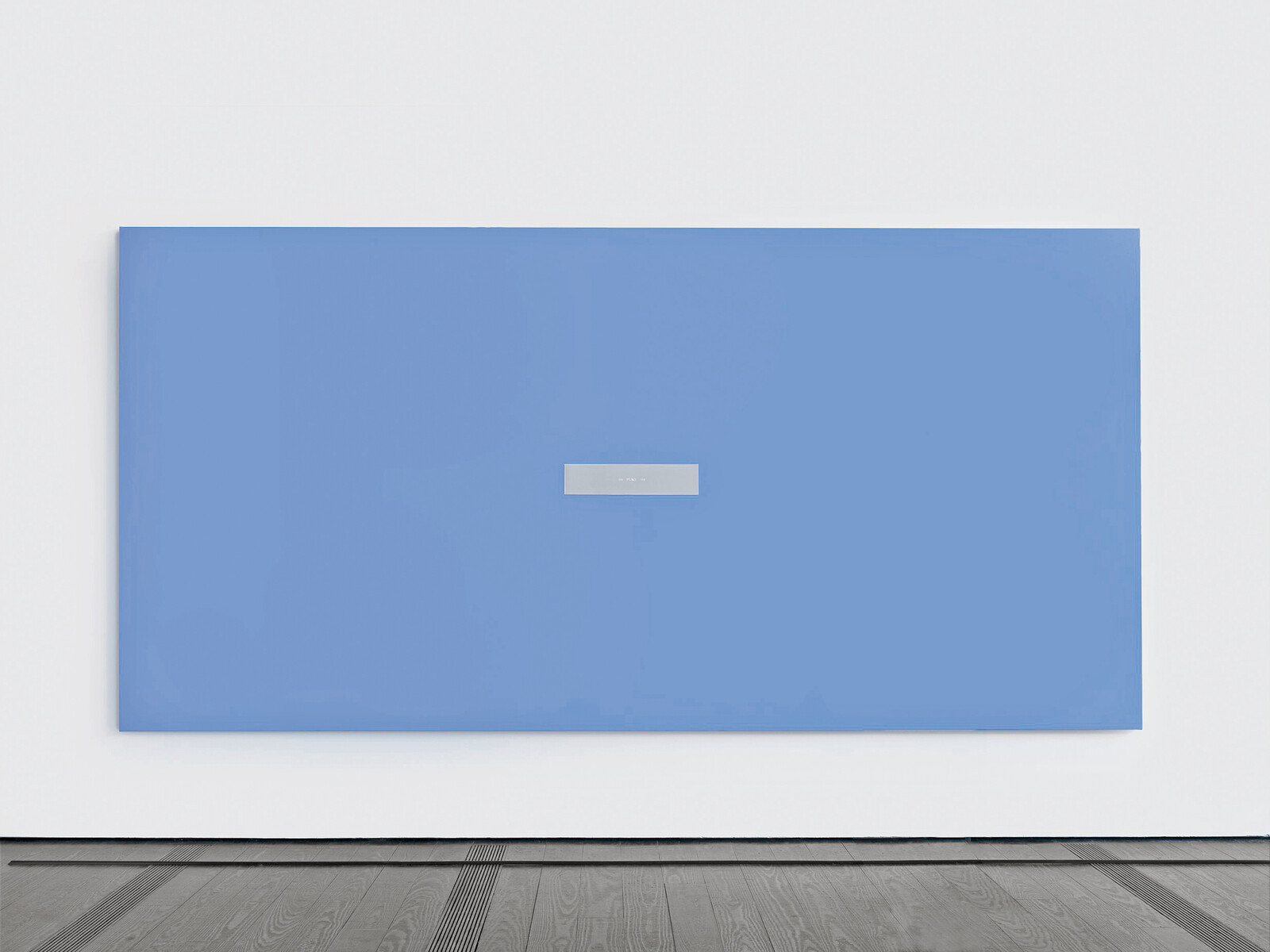

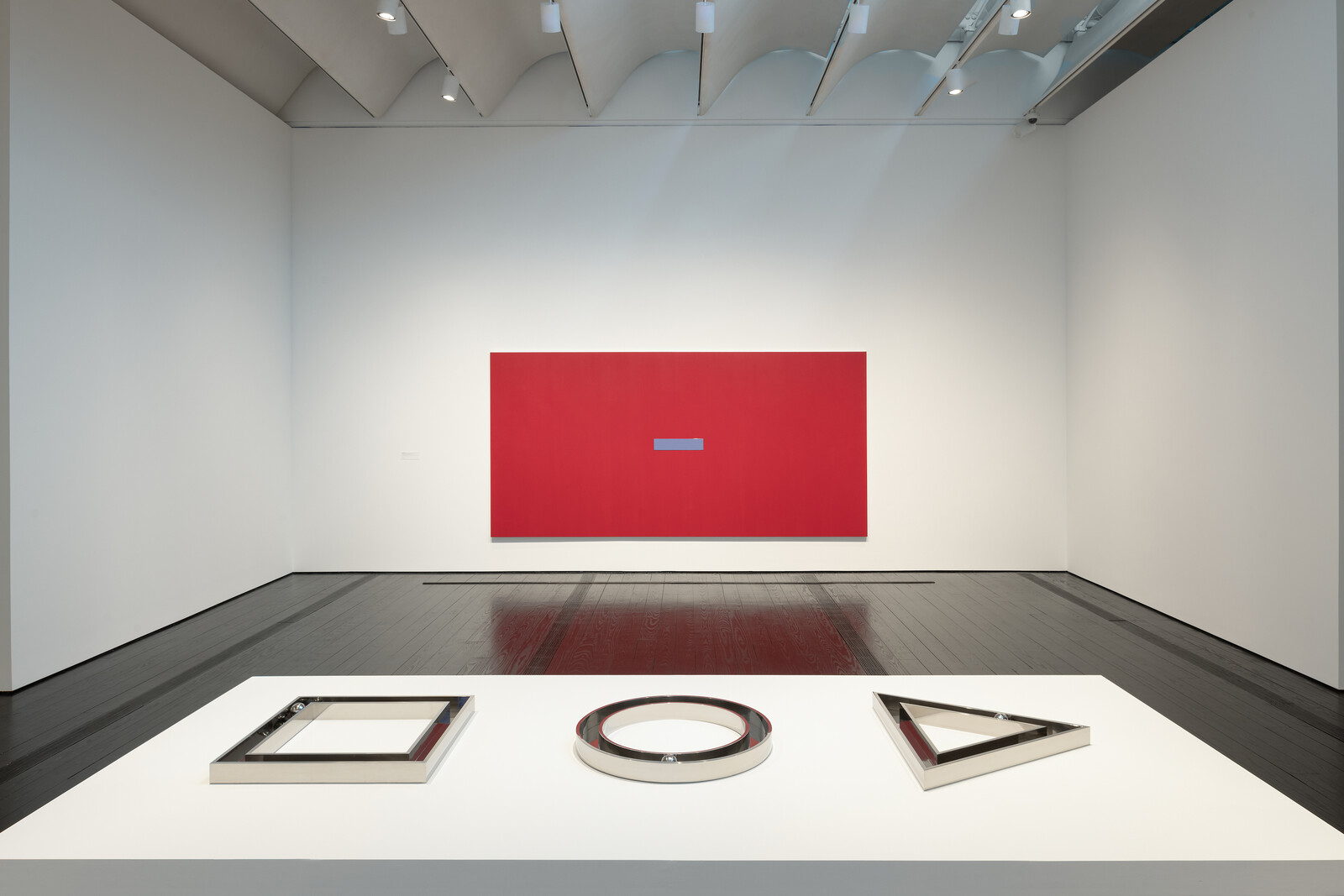

The narrative of the exhibition has but one lapse in judgement. In the penultimate gallery is a late diptych, The Statement Series (2011). These were made at the end of the artist’s life, when his stature allowed him to become the court artist of the Marshall Plan and conceive of work whose rhetoric was universalist in the worst possible way. The paintings are large, red-and-blue monochromes with steel plaques that pronounce “NO WAR NO” and “YES PEACE YES,” respectively. An admirable sentiment that falls flatter than the canvas itself. They are prudently excluded from the modest exhibition guide.

It is a dirty trick, I know, to judge the artists by their final attempts to secure their legacy. However, there is another piece by De Maria from that period that has a direct connection to the earlier work. From the late 1980s, the artist took to installing big granite balls, red and black, in France (Monument to the Bicentennial of the French Revolution 1789-1989, 1989-90, National Assembly, Paris), in Germany (Large Red Sphere, 2002, Kunstareal Munich), and Japan (Seen/Unseen, Known/Unknown, 2000, Chichu Art Museum, Naoshima), concluding a journey that started with the 1962 piece Adventures of Mr. Ball. In this whimsical work, a wooden ball, originally activated by the audience, rolls through a number of boxes with crudely drawn landscapes that designate “the desert”, “the mountains”, and “the ocean.” Never exhibited during De Maria’s life, the transformation of this modest joke into a gigantic monument is the most eloquent demonstration of the triumph of the American world order, whether de Maria wanted it or, quite possibly, not.

According to James Nisbet, De Maria’s Spheres are “deceptively complex objects” that “grapple with the fundamental limitations of attempting to generate pictures in an era characterized by constant but deeply fragmented experience of media.”3 This implies that the artist was conscientious enough to send his work up against the media landscape of the time. But what if the spheres are just physical embodiments of an artistic quest for power that has become irrelevant? With Minimalism being a staple of the North American museum-going experience, this might be a lot to ask, but hear me out: for a time, at least, we would be better off without it. The US has survived the mall, after all; why not the boxes that are its high-culture twin? If we can’t put it all in storage, it would be interesting to consider Minimalist work as the husk of a dead paradigm. If you’re too close, iconographically, to the marketing strategies of your time, your work will have an expiration date.

It may well be that in a not-so-distant future we will desire boxed insights once again. For now, however, it is probably fair to question the intellectual formations that made De Maria’s, and many others, careers possible. Looking back to Harald Szeemann’s exhibition “When Attitudes Become Form” (1969), still a point of reference for the art of the era and the curatorial thinking behind it, one wonders if it is time to dispense both with the attitudes and the forms. They both look like a forced continuation of the Modernist impulse, where the utopian projection and the geometric purity have finally met—on a parking lot.

George Rickey and Donald Judd, “Two Contemporary Artists Comment,” Art Journal, vol. 41, no. 3 (Autumn 1981): 250, https://doi.org/10.2307/776566.

William Severini Kowinski, The Malling of America (New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985), 22.

James Nisbet. “Surface/Sphere: Walter De Maria’s Geopolitical Dimensions,” The Art Bulletin, vol. 98, no. 3 (September 2016): 387, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43947933.