A year since first reading this review, in the arts library of the author’s alma mater, I remain utterly bewildered by its impassioned, personal rhetoric. Peter Plagens speaks with a proprietary and intimate knowledge of Los Angeles that neither reduces his role to that of regional gatekeeper, nor lapses into the vitriol that flows easiest from the pen. To defend his adopted city from encroaching optimism he chooses, rather, to measure the full mess from extremity to center and plumb the shallow histories of its asphalt face. So fucked a place has rarely been better written; and, contrary to present discursive apprehensions, Plagens’s belletrism performs a demonstrative service to his critical ethos.

—Tyler Coburn

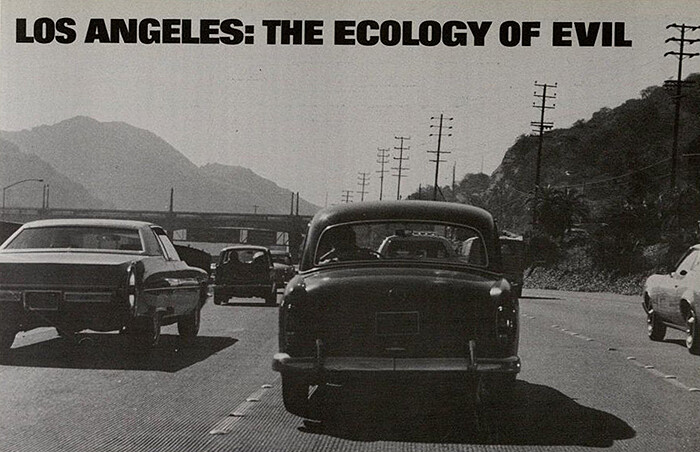

“Los Angeles: The Ecology of Evil”

The city of L.A., it ain’t the way the posters say that it’ll be. Behind the palm trees and chrome I find a stucco home, And another factory. —from “The San Diego Freeway,” an unpublished song by Dave Hickey

Los Angeles once had to defend itself against snotty Eastern culture critics, English novelists, and middlebrow gossip columnists like Herb Caen who, from Provincetown-on-the-Thyroid, condescendingly refers to “that city down south.” The implication was always that Los Angeles, the world’s most spacious city, was in a Culture-and-Sophistication League with Dubuque, Rochester, and Provo, that it was basically “bush” and that by luck or by golly it possessed none of the brittle, knowing sophistication derived from real big city problems. In the ’60s Los Angeles moved past Philadelphia in population into third behind New York and Chicago, held the Democratic convention, acquired a spate of major league teams, built several culture palaces and 1000 miles of freeway, suffered a racial upheaval, and generally enlarged/intensified itself into the malignant tumor of a Great American City. In fact L.A. succeeded so extraordinarily that now it finds itself plagued by a different observer: the chic debunker of current anti-L.A. Mythology (“God, you don’t wanna move there now. It’s so crowded now, and the smog… you wouldn’t believe…”) who finds that L.A. is really a groovy place in spite of its evils and often because of them, if you know how to look at it right. Ray Bradbury, with his noxious future-mystical treacle in “Los Angeles is the Best Place in America,” Esquire, October, 1972, is essentially harmless, but Reyner Banham, the English architect/pop scholar, has written a heavyweight “serious” book, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies (London, 1971) which is quite dangerous because it will have a trickle-down effect (i.e., the hacks who do shopping centers, Hawaiian restaurants, and savings-and-loans, the dried up civil servants in the division of highways and the legions of show-biz fringies will sleep a little easier and work a little harder now that their enterprises have been authenticated. In a more humane society where Banham’s doctrines would be measured against the subdividers’ rape of the land and the lead particles in little kids’ lungs, the author might be stood up against a wall and shot; as it is we must try to laugh through our tears at…Four Ecologies’ nearly comic ineptness.

“What I have aimed to do is to present the architecture (in a fairly conventional sense of the word) within the topographical and historical context of the total artefact that constitutes Greater Los Angeles, because it is double context that binds the polymorphous architecture into a comprehensible unity that cannot often be discerned by comparing monumental with monument out of context (p. 23).”

This airy frappe of light architectural history, generalized architectural description, and fly-by night sociology is halfway excused because it’s intended for a general, not professional, audience, and an English, rather than American or Californian, readership. Still, the average Scarsdale demi-intellectual can tell a post-and-lintel from an arch, and the English have long been smarter than ourselves about the “States” catapult to doom. Banham merely takes a quick perusal of the same old beaches, hills, plastic, and L.A. pop on the route of every Tanner Tour, jazzes it up with watered-down McLuhan and Robert Venturi (who are genuinely demented enough to actually like such crap), and fobs off as nutritious the same old conventioneer bullshit about “freedom” (mobility, sun, sex, affluence) for everybody which bloats L.A. with eager seekers and a quick-buck economy. Moreover, Banham’s prose is an embarrassing cocktail of officialese and hip; he uses or makes up ridiculous, un-euphonious slang I’ve never heard anyone here use: “San Mo” for the freeway or town of Santa Monica, “surfurbs” for the beach communities, and “autopia” for our car shtick.

I admit, however, to a proprietary interest in Los Angeles, the two-thirds of my total 31 years spent here blessing me with a xenophobic resentment of an outside architectural geewhizzer taking such delight in the outsized perversities slowly killing me, my friends, thousands I don’t even know, and Los Angeles itself. As a product of parents who saw every Hollywood film released during the Depression, the local public schools, and almost all the L.A. novels in the main branch library, I find it impossible to write dispassionately concerning this spangled pot-hole. I sold Herald-Expresses in a Gardena poker parlor, suffered beatings by the oddfellows of “Lil’ Temple” in Echo Park, obsessively cruised Hollywood Boulevard in high school, got laid in the back of Bradley Brown’s ‘49 Chevy convertible, and sucked around the Newport set when I was a Trojan fratboy. As an adult with my own family I’ve set up tiny households in mundanely representative communities: 1) Silver Lake—a guest house in an older, hilly, romantic, close-in enclave of LA.’s good life (drinks on the deck, amid eucalyptus leaves and a view of the reservoir); 2) Culver City—a classically dull stucco quadruplex on a wide street rife with kids, supermarkets, squealing street-modifieds, and that strange, depressing mist which floats inland on winter afternoons; 3) Long Beach—gray, quiet, not-quite-there, on the fringes of the beach set (Belmont Shores, Naples) and seediness (downtown, the arcades and whorehouses) where Ross MacDonald’s private dick, Archer, paid his dues; and the worst, 4) Pacoima—a jungle of campers, beer-bellies, asphalt, smog, crackerbox tract houses, littered shopping centers, pig women in platinum bouffants, and the overriding stench of hopelessness (a six-year-old kid walking to school through a freeway underpass with 12 lanes of obese traffic crashing by, and a visibility of a block and a half). Now that I’m hiding in the hills I wouldn’t live anywhere other than L.A. except as a Modem Master retired to the Spanish coast or Cornwall, but I remember the Pit well and my emotions regarding Baghdad-by-the-Sea are ambivalent; to reverse the old song line: “But when I love you, it’s ‘cause I hate you.”

Granted, Los Angeles shares quite a crop of downers with other cities and techno-industrialism in general. The failings of the Western democracies are manifest everywhere (what wrought that chamber of horrors, New York?), but in L.A. the sins of our fathers (Collis Huntington, Harrison Gray Otis, Phineas Banning, William Mulholland, Harry Cohen, Chief Parker, and Sam Yorty, to name but a few) comprise not the gradual accretions of the centuries, handrubbed with tradition into patinas of respectability, but are instead juxtaposed brutally on a magnificent landscape and climate, traces of whose virginities are still glaringly but infrequently evident. Just look down from a hill and you know how bad it’s being fucked up. Los Angeles is thus a city of extremes and it provokes either adoration or contempt. San Franciscans, New Yorkers, and Colorado hippies look down their hand-tailored, granola-filled noses at this brown-aired basin of vulgarity. Continentals, Okies, Londoners, Arkies, and visiting artists to the contrary warm their dispossessed souls on our sandy bosom.

The clichés are true: the sun is bright, the girls are flat-bellied and tan, the beach beckons, the buildings as well as the kids seem so young, everyone is loaded with discount store appliances, and minor iconoclasms like no tie at the office are the daily diet. Converts worship L.A. because of: 1) the ’60s boom, Everyman’s consumerist dream come true; 2) omnipresent pop chic, the “it’s so bad it’s good” syndrome, living Warhol’s life without the bother of that stupid silver studio (a local artist said he liked L.A. because of a “certain raw energy”; doubtless he would have noticed a “purposeful austerity” at Auschwitz); or 3) nostalgia for the “old” L.A. of Raymond Chandler, the Brown Derby, Gilmore Stadium, the “P” car, and lunches at Clifton’s cafeteria among the fake waterfalls and colored lights. Banham understandably accepts these chestnuts, but swallows them whole within #1, above, justifies his taste with a hype #2, and has sampled just enough #3 (…Four Ecologies contains a “Drive-In Bibliography,” cute and incomplete) to delude himself that he has genuine insight. But within the “total artefact” he’s mistaken salient limbs for the trunk, overestimated branches (“freedom” through automobiles), and ignored others (sources of capital) until we’re left with a fattened hifalutin tourist brochure.

L.A.’s worst quality is a spiritual disease, a thinly disguised sense of hopelessness and frenetic ennui. Amid a growing characterlessness (Von’s markets, Ralph’s markets, Lucky markets, Alpha Beta markets, and Boys’ markets relentlessly plopped along the wide, flat, smoggy streets of the great deserts of complacency and reaction in the southeastern suburbs, Orange County, or the Valley), victims seek instant gratification in sparklefront apartments, food photographs on Denny’s menus, aggressively customized cars, unmanageable choppers. They have a shabby booster-club belief in their own places as cogs in some universal gear wheel of free enterprise “progress.”

Most Southern Californians are simple folk from the plains and southern states (Long Beach is called “Iowa’s largest seaport”) without citified tastes for philosophical despair. Los Angeles has no cultural traditions to speak of because the city is really only about 40 years old (the rest is commemorative plaques and jerky, grainy movies); no one ever went broke underestimating our taste.

Perhaps it’s the weather, the supposedly generous “instant” welfare/unemployment benefits or the plentitude of cheap fresh fruit, but Los Angeles produces the greatest per capita crop of creeps in the Western world: realtors, record producers, agents, interior decorators, car dealers, and artists are represented in abundance; there are more color-coordinated guys named Sherm and Murray driving white Pontiacs, more upper-middle-class WASP beach hippies standing around Camaros in front of good restaurants, and more sidebumed Archie Bunkers from Lockheed towing gleaming tonnage of airstreams and dune buggies behind their Country Squires than anywhere else you care to think of. L.A. is an elusive place: all flesh and no soul, all buildings and no architecture, all property and no land, all electricity and no light, all billboards and nothing to say, all ideas and no principles. Within “Greater Los Angeles” more than seven million souls wheeze for survival, and their children will give us 10,000,000 soon; they cannot be written off. Los Angeles is the harbinger of America’s future—if we can save the children of Los Angeles, we can save anybody, everybody. But Banham, who’s exchanged the progressive architect/planner’s reformist fervor for establishment hip, doesn’t see it that way.

Banham’s four “ecologies” (a term which seems less indicative of a broad investigation than it does a cop-out on ever getting down to architecture or Banham’s universal, antipop villain, planning) are “surfurbia,” “foothills,” “the plains of Id,” and “autopia.” “Surfurbia,” where Banham begins, runs from the far edge of Malibu southeast to Balboa Island in Newport Beach, some 70 miles. To my mind and experience that wavering strip, compared to the increasingly infrequent interstices of natural coastline, is L.A.’s second monument to spoilage and catastrophe as a result of cars and freeways. Driving south on U.S. 101 you are treated to a claustrophobic vista (collapsible cliffs on one side—every once in a while somebody loses a house) of the ass-ends of private beach homes (if you can see through the parked cars), cheesy motels and a skid row in Santa Monica, delapidated, deserted Venice except for the higher rent artists, the abandoned tract house in Playa del Rey (jet takeoffs literally blew their minds), a series of majestic refineries and SoCal Edison installations, the lovely but exclusive last outpost of the landed gentry, Palos Verdes and Rolling Hills Estates, wonderful San Pedro, Los Angeles’ Perth Amboy, downtown Long Beach, the still halfway decent backwaters of Seal Beach (craftsmen city) and Huntington Beach (surfing championships), and finally Newport Beach, the leathery tennis matron capital of the world. It is, in short, cluttered and trashy, too much privately owned (or squeezed by private land), and populated, especially in Manhattan Beach, by self-righteous, what-kind-of-a-man-reads-Playboy light-industry hedonists.

Banham thinks it promotes popular spirituality:

” ‘Give me a beach, something to eat, and a couple of broads, and I can get along with material things,’ said a Santa Monica bus-driver to me, summing up a very widespread attitude in which the pleasures of physical well-being are not “material” in the sense of the pleasures of possessing goods and chattels. The culture of the beach is in many ways a symbolic rejection of the values of the consumer society, a place where a man needs to own only what he stands up in—usually a pair of frayed shorts and sunglasses (pp. 38–39).”

Trouble is you can only take your frayed shorts, jug of wine and thou down to the beach if there’s access, a public beach, and no hot water waste; the land distribution—ocean-front homes, fenced-off industry, and the recent rampage of marinas (used car lots with sails)—is in fact contrary to the nature of a coastline.

True, L.A. has the beaches, and most views of them available from any automobile are slightly more exhilarating than the grandeurs of America’s breadbasket or those sooty cities back east; but almost nothing has been done for or with them, only to them, because Los Angeles is still an almost unbridled free-enterprise town. When they build the nuclear generating stations (needed to power all those electric bun-warmers SoCal Edison and the DWP begged us to buy when times were hot), highrise geriatric ghettos, and the rest of the plastic marinas, it’s going to be worse. As of now, California’s ballot sports a “coastline initiative” creating a mile-wide zone in which special commission permits are required to build, and which cause the mayor of Long Beach, among others, to foam at the dentures because it endangers another classic Southern California builder-government, sweetheart-deal, “civic center” rip-off.

Banham perceives the second “ecology,” the foothills, equally benignly:

“That is what foothill ecology is really all about: narrow, tortuous residential roads serving precipitous house-plots that often back up directly on unimproved wilderness even now; an air of deeply buried privacy even in relatively broad valley bottoms in Stone Canyon or Mandeville Canyon. Even more than the second-growth woodlands of Connecticut or the heathlands of the Kentish Charts, this is landscape that seems to cry out for affluent suburban residences, and to flourish when so employed (pp. 99–100).

I can vouch for part of that—the desirability and illusion of privacy—having just come out of the Pit into the hills of the well-equipped faculty liberal. (It has its drawbacks, however; already I can feel the outrage slipping, harder to get worked up about L.A.’s automotive-capitalist rot of the psyche when outside your window is a silver-dollar eucalyptus instead of the power lines of Pacoima; I’m all right, Jack…) Banham says, “…the Rolls-Royces are still outside the door of the Balcker house in Pasadena and the Ferraris still negotiate the twisting roads of Palos Verdes as to the manner born, the Continentals turn in the forecourt of the Bel Air Hotel—and well-bred hooves still clatter in Mandeville Canyon” (p. 102), but the hills are not without their shady side. Natural public-use areas, they’ve been gouged for single building sites and sub-developments, and packed with houses which often fail to meet even the lenient county codes, and which with frightening regularity come tumbling down the mountainside in the wake of winter rains (Country Club Drive in Burbank may be sliding still). The hills infuse a sneaky attitude of innate superiority into nonessential people like clothing salesmen, talent scouts, and me, but their greatest danger is physical:

“As the population of Los Angeles has doubled and then some, occupying the flatlands, real estate men, contractors, and homemakers seeking space and amenities have taken to the hillsides, formerly considered too steep, too inaccessible, too hard to build on. The FHA [Federal Housing Administration] and almost no banks would lend for hillside homes, which tended to be original in design, picturesque, eccentric, but not sure commercially. From around 1945 on, up and in went the skiploaders and bulldozers and big eight-wheeled trucks, to hack at primeval green slopes and reduce them to crumbly, desolate cliffs, ripping at ancient creek bottoms and covering it flat with sterile inner layers. Often contractors, as they skimmed the tops of the hills, or as they tan their arbitrary roads up hillsides, or as they gouged out little shelf-like ‘pads’ for bungalows or castles, had the machinery efficiently shove tons of loose dirt and brush over the side, where it slouched, loosely held up by bushes. ‘Just shove’er over. The brush’lI hold’er!’ ” (Richard C. Unard, Eden In Jeopardy, New York, 1966, p. 111).”

Since the hills are private property, all that counts is that the people who buy the houses and lots dig what they’re looking at.

“While grading ordinances, like building ordinances, concern themselves with safety to property or life, they say nothing about appearance, about esthetics. The natural profiles of the peaks, the lines of the crests, the folds of the hills, the long sweeps of flowering bushes, the clustered oaks and sycamore groves in the winding creek bottoms, the occasional rock formations and gorges—the whole age-old balance and repose that have given Southern California one of its notable charms—are being turned by bulldozers and dollar chasers into terraced quarries and open-pit mines and invisible profits. The open pits are unlike the glory holes dug for Minnesota iron or Nevada copper. Those are work-places only. These Southern California glory holes, though bleak and sterile as Utah’s coppery Bingham Canyon, are for residences only, and here the prosperous build mansions and oval swimming pools, park their long, plump Detroit cars, and keep ahead of the Joneses. To some more sensitive souls the bulldozed desecrations of hillside scenery are part of a tasteless trend that violates inherent charm and natural beauty and makes much of the ‘Southland’ not worth living in (Lillard, pp. 114–115).”

The Bel Air fire of 1961 (over 200 homes destroyed) worked up a great lather about planting the hillsides, stricter fire laws, etc., but the 1970 Malibu-Chatsworth fire was even worse in terms of acres burnt although few houses were incinerated. Thus all the fuss about building codes generated by the 1971 earthquake (whose epicenter was way out in Saugus, precluding a true metropolitan disaster by 90%) augurs for almost nothing in de facto improvement (an election bond issue to rebuild pre-earthquake code schools failed only nine months later). For the past several years slow, overladen, trash trucks have grunted their ways up the Sepulveda Pass and other hilly trails to dump megatons of refuse to make nice, flat underpinnings for upper-bracket Ozzie-and-Harriet subdivisions; a tremor only a mite more vigorous than a sonic boom will settle the whole business like a bag of potato chips in a cyclotron, a possibility which ruffles even Banham:

“Really big cropping like that at the top of Topanga Canyon involves cutting deep into the underlying geology, and totally filling the ravines and other drainage runs, so it becomes difficult not to entertain apocalyptic queries about how some of these developments are going to settle down—and where! Such large-scale triflings with the none-too-stable structure of an area with high earthquake risk seems more portentous as a direct physical risk to life and limb than as a lost ecological amenity (p. 109).”

A few rhetorical disclaimers (“these central flatlands are where the crudest urban lusts and most fundamental aspirations are created, manipulated, and, with luck, satisfied”) notwithstanding, Banham sloughs off what he calls “the plains of Id” (yuk) and what I call the Pit. He devotes only 17 of 250 pages to the guts of L.A., an area he dismisses as “the small percentage of the total metropolis that urban alarmists delight to dwell upon” (p. 161).

Conceding that “there is a certain underlying psychological truth about it,” he passes it off as the land-deal equivalent of the least of Freud’s psychoanalytical territories. L.A. is physically the world’s largest city and most of that area is the Pit; add on the “total metropolis” and you simply annex the Valley, the San Gabriel Valley, and the Berchtesgardten of L.A., Orange County—altogether, the widest, dumbest, most spreadout, forlorn acreage of the Pit. Most of the flakey stucco buildings and the last-gasp Bauhaus insurance company redoubts are in the Pit. And for damned sure most of the people (save the fortunate few holed up in the coastal or hillside slivers) live, work, and run down to the Sav-on for Tampax or cigars in the Pit. If the world’s image of L.A. is indeed “an endless plain endlessly griddled with endless streets, peppered endlessly with ticky-tacky houses clustered in indistinguishable neighborhoods, slashed across by endless freeways that have destroyed any community spirit that may once have existed, and so on…” then the world is right. L.A.’s essence is Gardena, Downey, or Mar Vista on a smoggy Monday afternoon, not the Hollywood Hills or Laguna Beach on a clear Saturday night. The straw man (“endlessly griddled,” etc.) Banham attempts to demolish is quite real, and the insights (“four ecologies” offered in replacement are gilded versions of the chapters of a Chamber of Commerce guidebook.

Such distortions are not, however, newborn with Banham; architectural literature on most cities ignores the daily grind, the millionfold smalltime commercial transactions, the lives of the workers and shopkeepers, police and criminals, housewives and teachers, and unemployed and elderly in favor of the few immediate features which apparently distinguish them from other cities. Thus London is West End, Archigram, the damp stones of history, and some outlying planned villages; Paris is the Eiffel Tower, quaint narrow-streeted neighborhoods, students in cafes, and taxicabs; Barcelona is Gaudi and the beach; New York is Fifth Avenue and muggings. Banham’s errors are more depressing because he purports to liberate us from the tyranny of big-time architectural monuments in favor of everyday pop; but he ends up in Beverly Hills and the beaches and all is lost. The causes are Banham’s general outlook and the people he hangs around with who are hardly a cross section. He’s at least a capitalist sympathizer, halfway believing that what the people buy is the best after all (but what the people get is usually what the entrepreneurs can get away with offering), and, in other articles, an advocate of the tract-builders as the saviours of architecture; so Banham is hardly the one to give us a Marxian analysis of the class structure of L.A. and what the monopolies (banks, savings-and-loans, oil, insurance, public utilities, and the division of highways) wrung out of it.

Among those whom Banham thanks in the prologue are David Gebhard, an architectural historian safely ensconsed in bucolic Santa Barbara, Art Seidenbaum, a round-and-about columnist for the Times, Irving Blum, the art dealer, Ed Ruscha, who surreally prettifies L.A.’s banalities, Mike Salisbury, the English art director of the sharp but defunct West magazine, and a raft of USC/UCLA academics—a collection of people whose in-city trips east of Main Street or south of Olympic could be counted on Mickey Mouse’s fingers. It’s a wonder then that Banham comes up with a nice descriptive paragraph:

“It is without doubt, one of the world’s great urban vistas—and also one of the most daunting. Its sheer size, and sheer lack of quality in most of the human environments it traverses, mark it down almost inevitably as the area of problems like Watts, which lies only a couple of miles east of the very midpoint of the Normandie Avenue axis. In addition the great size and lack of distinction of the area covered by this prospect make it the area where Los Angeles is least distinctively itself. One of the reasons why the great plains of Id are so daunting is that this is where Los Angeles is most like other cities: Anywheresville / Nowheresville. Here, on Slauson Avenue, or Rosecrans, or the endless mileage of Imperial Highway, little beyond the occasional palm tree distinguishes the townscape from that of Kansas City or Denver or Indianapolis…the only parts of Los Angeles flat enough and boring enough to compare with the cities of the Middle West” (pp. 169–173).

Yeah, but in the Middle West you can breathe once in a while and get out to the “country” by driving ten miles; in L.A, you just keep rolling by one faceless suburb after another. Try stringing Monterey Park, Alhambra, EI Monte, and West Covina to the east, or North Hollywood (the porno capital of the U.S.), Van Nuys, Sepulveda, and Northridge out in the Valley. Not so long ago I bicycled from Pacoima to Laguna Beach and cut directly southeast across such acrid smears as Huntington Park, Maywood, Downey, Paramount, Bellflower, Norwalk, and Buena Park, contemplating suicide (depression, not fatigue) every five miles. (I recommend bicycling for a) an object lesson in the ugliness and arrogance of cars and that most air pollution occurs a meter or less from the ground, and b) a true, empathic gauge of what the wide-street wasteland free enterprise development has wrought. The attribution of “miles and miles of nothin’ but miles and miles” should go to L.A. instead of Texas.) Richard Neutra remembered:

“When I first came to California, merely the green strip along the coast of the Pacific was settled. The desert inland, the ‘wasteland’ was the playfield of the devil. Now it is added to the realm of the realtor. This whole vast territory is studded with industrial and military establishments, rocket-testing stations, and what have you, and house-wives have resigned themselves to follow their men who are occupied here into this barren land. Every family has two cars which, glittering, then later fading out, stand around in the sunshine. And father, mother, and kids, hang on a telephone plus its pole, standing against the sky like a sore thumb, so that from their grand property they can talk over the distance to other grand property-owners of half a neglected acre or more” (Life and Shape, New York, 1962, pp. 340–341).

The result is precisely that “endlessly griddled plain”; a bit of it permeates any American city, but it is the big flat ruby in L.A.’s crown, and its glitter is sheer desperation.

No one expects a Falling Water, Seagram’s Building, Kimball Museum, Ronchamp Chapel, or geodesic dome in every block—a 99% divinely ordained frequency of crud obtains in architecture as well as movies, detective stories. Conceptual art, breakfast cereals, and art criticism—but the urban / suburban sludge is only silted higher by the incessant spread of American cities. Los Angeles, because of its youth, cancerous automobiles, and naturally expansive basin is extremely susceptible and becomes in some cases (Watts) a horizontal, open-air prison.

The chief conspirator is, of course, the automobile, a fact which Banham excuses (to preserve his fancy of Everyman’s Wings) by citing previous layers in a “transportation palimpsest”:

“The fact that these parking-lots, freeways, drive-ins, and other facilities have not wrecked the city-form is due chiefly to the fact that Los Angeles has no urban form at all in the commonly accepted sense. But the automobile is not responsible for that situation, however much it may profit by it. The uniquely even, thin, and homogenous spread of development that has been able to absorb the monuments of the freeway system without serious strain (so far, at least) owes its origins to earlier modes of transportation and the patterns of land development that went with them. The freeway system is the third or fourth transportation diagram drawn on a map that is a deep palimpsest of earlier methods of moving about the basin” (p. 75).

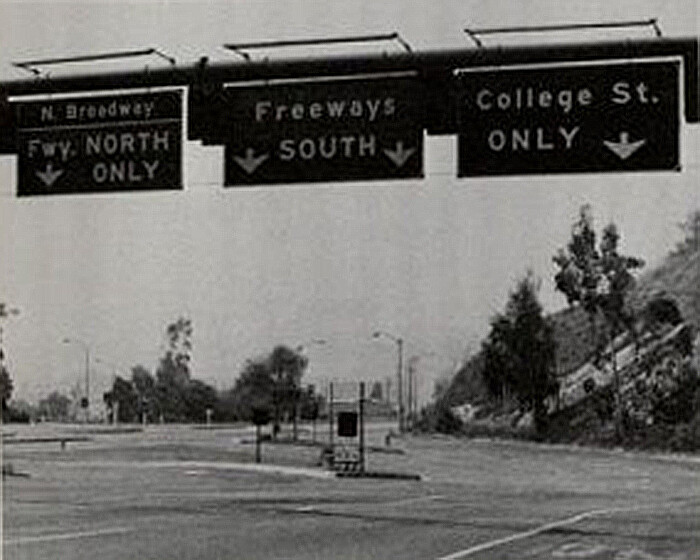

Such drivel—even with mercy toward its logical marvels (L.A. has no urban form ergo it hasn’t been wrecked), glaring idiocies (absorbing the monuments of the freeway system without strain!), and comical vagaries regarding “earlier methods of moving about the basin” (foot, horse, railroad, and rafts floated down the sewage canals?)—ignores several obvious facts. They are: 1) if the Pacific Electric Railroad, the efficient “red cars” were all that influential Los Angeles would be a network of nodular communities along a network of roads, margined by copious open space, and not a continuous blanket of pink stucco; 2) a wagon journey from downtown to San Pedro used to take three days, hardly the stuff of which megalopolitan spread is made; and 3) anyone who remembers L.A. in 1955 or 1960 knows they’ve since built lots of “freeways to nowhere” with the houses and population following afterward, such as the northern extension of the Hollywood Freeway, the western Ventura, the eastern San Bernardino, and the San Diego in Orange County.

The automobile is responsible for the bane of L.A.’s existence, a merciless spread-cum-congestion, and was present as a cause long before the advent of freeways; on this point, Banham almost manages to fully rebut himself:

“Yet real estate was to be one of the two factors that undid this masterpiece of urban rapid transit. As subdivision and building promoted profitably increased traffic, they also produced more intersections and grade crossings where trains could be held up and schedules disrupted, so that the service began to deteriorate and street accidents began, in the 1920’s, to give the Big Red Cars a bad name. And what was obstructing the grade crossings and involved in helping to cause the street accidents was the other factor in the undoing of the PE: the automobile” (pp. 82–83).

In 1921 an entrepreneur named Ross bought 18 acres along an under-trafficked street called Wilshire. But the land was about midpoint between downtown and the beach by Beverly Hills. Ross bought the land on the speculation that Los Angeles and America were due for a linear shopping center commodious to the growing stream of automobiles. The area is now the “Miracle Mile,” six lanes of bumper-to-bumper clientele fenced in on both sides with great white emporiums of literally everything. There’s no record of how much Ross made on the deal. A dozen years later Lloyd Aldrich became Los Angeles city engineer and, with the precedent of New York State’s “parkways” in his head, hustled up $100,000 from the likes of the president of Bullocks for a “study” which ultimately concluded in 1939 that L.A. ought to have an ante of 300 miles and a jackpot of double that of “urban freeways.” With the state and the PW sweetening the kitty, Los Angeles built the Pasadena Freeway (née Arroyo Parkway) a year later. Ever since the freeway has been a self-fulfilling prophecy:

“The freeways are necessary also because the Los Angeles area is the world’s first industrial complex based upon highway transportation. This led the county to be first in the nation to adopt a distribution of factories and warehouses, homesite subdivision and schools and shopping centers, all of which in turn means beginning new roads, new freeways every day, every week” (Lillard, p. 197).

And in spite of its ransack of Southern California, the freeway system rolls on, an octopus to make Frank Norris’ robber-baron railroad look like the model train layout in grandpa’s garage. Much of the freeway system is financed by the sacred Highway Trust Fund, a scheme by which the 11¢ per gallon gas tax avoids absorption by the general revenue fund, and is locked into a special fund usable only for highway construction. Thus, the more cars the more gas tax, the more tax (there’s always a huge surplus) the more freeways, and the more cars. Only very recently, over the cries of the Auto Club, oil companies, etc., has the trust fund encountered attempts to use its riches for rapid transit.

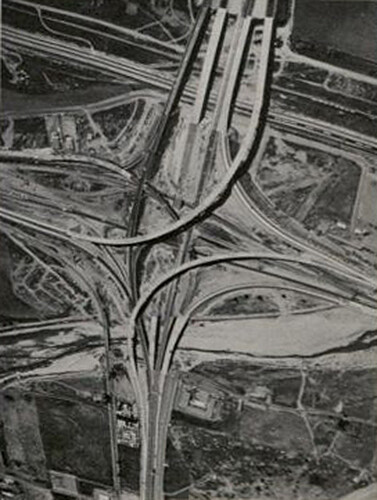

At present two-thirds of downtown Los Angeles is occupied by parking lots and structures, streets, and freeways; in L.A., Orange, and Ventura counties fully two acres in every 100 are sacrificed to freeways (the Automobile Club says “only” two percent!). The standard argument (highway commission, oil, car, and tire companies, the Auto Club) in favor of freeways is twofold: quicker and safer. But it isn’t quite that simple, even restricted to those initial points: 1) freeways doubtlessly foster more cars (“hell, Mavis, we can move out to Fountain Valley, and I can let you have the old buggy and get myself a new Dart and drive to work in 20 minutes now that they’ve put the new freeway through”) and encourage neglect of surface streets (streetcar tracks are still embedded in Pico Boulevard). If all those freeway-spawned cars were shunted off to unkempt surface streets, sure, it’d take years to get anywhere; 2) “safety” is computed in injuries / fatalities per passenger mile; Mavis’ old man must now do 80 miles a day instead of 20. Beyond that freeways, consuming 28 acres per mile of road, siphon off whole Balkan states from the tax rolls, reduce the value of all but industrial adjacent land (noise, fumes, ugliness), screw up what parks L.A. has (fewest park acres per capita of any U.S. major city; the Golden State Freeway has made the zoo side of Griffith Park a first-class pain), and sabotage the scenery (e.g., the Ventura Freeway in Eagle Rock). But worst, freeways have destroyed or aborted the very egalitarianism Banham and the highway commission think they promote; the great ivy-covered walls or ditches which carry the eight-lane flow are as effective as cyclone fences or moats in demarcating ethnic ghettos, letting upper-middle-class whites roll from the Valley or Hollywood Hills to the beaches without soiling their gazes on the poverty of south-central Los Angeles (one of the first defiant manifestations of the Watts riots was sniping at cars from overpasses on the Harbor Freeway).

Lately the construction of new freeways has been fought, but the victors have been more affluent communities (Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, Newport Beach). It’s a tougher row to hoe when a blue-collar pocket like Cudahy and black Watts try to fend off the Century Freeway (which at a length of 17 miles and a cost of a half a billion dollars could be paved in dollar bills 107 deep!). Since the freeway assumes that everyone has a car or that it’s a civic duty to own one, public transportation in Los Angeles is nonexistent—a joke, a myth, a tragedy. The L.A. Rapid Transit District, one of the world’s great misnomers, is hardly the fault of the beleaguered drivers of slow, hideous, two-gear, oil-burning buses (“Oooh, those buses, they’re so dirty and smelly; we’re lucky we don’t have more of them and can drive our own cars instead,” the local lemmings say), or the street-level operatives of the RTD, but rather the stunted child of a cruel orphanage. Among its preriot feats was being able to bring a black worker from Watts to a downtown job all of six miles away in a little over two hours, via three transfers. Try going from Hollywood to the beach, or from Highland Park to County-USC Hospital, or try going anywhere.

“One way or another, a member of the L.A. middle class should have his (or her) four wheels to be effective, and few but the very poor—the Negroes, Mexicans, old people, and less fortunate students—are without them. These poor may ride on buses, but preferably for short hauls only, as a citywide bus trip takes up hours. There is no other cheap way to move unless one counts walking, which is thought eccentric, is seldom adequate for the time and distance involved, and is not encouraged by the city’s layout: some streets have no sidewalks along them; many others are dreary stretches scaled to the automobile; and in some sections, furthermore, pedestrians run the risk of being picked up as vagrants unless they are carrying canes, leading dogs, or otherwise demonstrating a leisure-class status.” (Christopher Rand, Los Angeles: The Ultimate City, New York, 1967, pp. 53–54).

A typical Angeleno rides to and from work, to and from shopping, and to and from the Dodger game or the swap meet in a fat, soft, sealed, rolling juke box, alone with his thoughts, rock music, Sigalert bulletins warning of congestion of the freeways, or his kids giving the finger out the tailgate window. But everybody doesn’t have a car.

“…there must be people on those buses who never, or hardly ever, ride in cars. People to whom distance is always measured by waiting time, and crowded push and shove, and little pink pieces of paper for transfers, and then the walk to the final destination. Driving, as most of us do, whizzing along, we remain comfortably ignorant of all the old and poor and tired people huddled on buses, or benches, windy corners, cold walls, dirty windows, thick perspiration, air, jouncing and sliding along the streets, lurching and bumping between corners, surrounded by strangers, late, hurried, and uncomfortable.” (Liza Williams, Up the City of Angels, New York, pp. 47–48).

I’m a pretty good driver. In 16 years of putting between 16,000 and 18,000 miles each on various cars I’ve been guided by the monolith on Jupiter into having no accidents either as perpetrator or victim, and only three paltry moving violations. I drive if possible with the window down and the radio off so I can hear the enemy on my flanks; both hands are on the wheel and I pay attention like a goddamned hawk because as good as I am the L.A. freeways are the great meat grinder. I don’t know how in hell tourists survive even half a day on the ramps and causeways, in the fool’s paradise of attempting to navigate by the huge green overhead signs. The first thing you have to know is who to watch out for: Valley housewives in Chrysler wagons filled with bobbing towheads sliding across three lanes full bore at 80 mph to make the off-ramp nearest the Safeway; dented, matte-finish VW buses crammed with stoned hippies and ecology flag stickers doing 25 mph up the Cahuenga Pass in the center lane; balding copper tubing salesmen with sex problems taking it out in ludicrous stock fake-racing cars named “‘Cuda,” “Mach 1,” “Heavy Chevy,” and “240Z”; eight Chicano low-riders hunched in a chartreuse ‘64 Chevy riding three inches off the pavement with dark brown windows all around, “Hold on, I’m comin’” scripted flossily on the rear side glass, no shocks at all, and beating you to the divider strip in a rumble of accelerating macho; contented, hog-jowled execs wallowing in Mark IVs or Cadillacs oblivious to everything outside the ice-cold air-conditioner and blue windows; precarious, tilting campers christened “Hal’s Corral” wobbling on the hazard strips threatening to drop the superfluous Honda on your hood; and other smug, self-congratulatory, “conscientious,” darting drivers of inconspicuous small sedans, like myself.

The second thing you have to know is the lay of the land. A frequent 25-miler for me is Pasadena to Westwood or Venice. On the south-bound Pasadena Freeway you can do five or ten mph faster than the signs if you accelerate through the curves, but watch out for bad lane drivers ‘cause it’s an aging, narrow freeway. There’s a nifty Chicano with a reverse bank going over the Golden State, but then you gotta get out of the left lane quick, because it slows suddenly at the Civic Center off-ramp. Bear to the left through the Stack, but watch the brake lights when the Hollywood melds with through traffic. The exit to the westbound Santa Monica is a bitch; you hafta filter through cars coming on from downtown, avoid the slowies gelling off at 9th Street, the undecided sudden-brakers at the transition road, more panic (and worse; I’ve never not seen a near-accident) at the Santa Monica / Santa Ana cleavage. Once past that stay left, but watch for sudden passers on the right trying to slip by before the onramp narrows on the Santa Monica. For some unknown reason, the far left lane always slows around La Brea (braking for the curve at Robertson?) but you can do 70 mph after that.

“…so Maria lay at night in the still of Beverly Hills and saw the great signs soar overhead at 70 mph, Normandie ¼ V ermont 3/4, Harbor Fwy 1. Again and again she returned to an intricate stretch just south of the interchange where successful passage from the Hollywood onto the Harbor required a diagonal move across four lanes of traffic. On the afternoon she finally did it without once braking or once losing the beat on the radio she was exhilarated, and that night slept dreamlessly.” (Joan Didion, Play It As It Lays, New York, 1970, p. 16).

Outside the occasional joys of driving (simply being glad it’s not the rush hour) and the relief at not being one of the economically infirm who take the bus, the assumption that near-universal automobile ownership is near-universal happiness couldn’t be more in error. You have a car in L.A. not because you want one (as you might have a Fiat in Paris), but because you don’t know any better or because there simply isn’t any choice. You must buy all that metal, rubber, and gas for your very own, endlessly pilot your own ship and ride your own shotgun, and eternally keep that weathered throttle to the floor to keep the bastard behind you off your bumper. It is absolute madness. Look around you on the freeway: does that bewildered mother of the drooling infant in the tattered plastic child’s seat want to be a rally driver two hours a day? Or the pensioner in the 20 year-old Plymouth? Or the tired shop foreman grinding home after a day near the furnaces? If they had a choice: hell no. But the presiding spirits of Los Angeles, with trendy assists from visiting hipsters like Reyner Banham (“…the place where they spend the two calmest and most rewarding hours of their daily lives,” p. 222), say you gotta. You gotta until somebody comes through the divider and crushes your legs, or until you move to Oregon, or until, as seems more likely every day, you simply cough to death with everyone else. But Banham sees the automobile differently:

“The private car and the public freeway together provide an ideal—not to say idealized—version of democratic urban transportation: door-to-door movement on demand at high average speed, over a very large area. The degree of freedom and convenience thus offered to all but a small (but conspicuous) segment of the population is such that no Angeleno will be in a hurry to sacrifice it for the higher efficiency but dramatically lowered convenience and freedom of choice of any high-density public rapid-transit system. Yet what seems to be hardly noticed or commented on is that the price of rapid door-Io-door transport on demand is the almost totaI surrender of personal freedom for most of the journey” (p. 217).

If in his last sentence Banham is talking about the driver’s inability to converse, look at the landscape, read, sleep, or plan the day ahead while riding the freeways, he’s right; if he means that any monorail, subway, or bus system will deprive the passenger of an impulse exit at Melrose, his priorities are sorely askew. In the ‘50s and ‘60s the hue and cry was to keep the economy hot; since the lynch-pin industry, steel, depends on the car-makers, the citizen was asked to do his part in providing Detroit with another 8,000,000 new car year. Now we know we are running out of steel, coal, rubber, and land to pave, and that the private car, with its 4,000 lbs. of rolling gear per passenger, one heavy, self-contained combustion engine per passenger, four gallons of gas per hour per passenger, and exorbitant street footage per passenger is the worst system anyone could deliberately design.

The “convenience” is rapidly fading, too; I know another BMW driver who computed his first two years’ operation in L.A. at 26¢ per mile—as, parking, insurance, repairs, and depreciation. In spite of an astounding car population (5,000,000 for seven million people!), the car is hardly “democratic”: it has created the worst, omnipotent oligarchy in the division of highways, chained us to the mercy of the oil / insurance / concrete / Detroit plutocracies, and exiled a peasant class of those who don’t / can’t own automobiles—the old, poor, and very young. The poor (even moderately poor) suffer worst. To have a job in L.A., or even to look for one, you must have a car; but to have a car you must have a job. The only alternative is the shady, usurious, used car dealer (“transportation cars for as low as $200”) or loan sharks; after this it’s the credit garage and the “assigned” risk insurance (as much as $600 per annum). The man who receives traffic tickets for driving too slowly, a frequent occurrence on the freeways, where the minimum speed is 45 mph, or faulty equipment, is more often than not a poor black or Chicano struggling to do a menial job. It’s little wonder that the holiest spot for selling Muhammed Speaks, the militant Muslim paper, is down at Wall and 8th Street, where hundreds of blacks come daily to pay their traffic tickets. But it breeds in all of us a callousness (you are taught to keep going when you see a pile-up on the freeway, lest you tie up traffic and / or get yourself killed), superiority (cursing pedestrians who dare slow up your right turn), and a sense of unreality (who cares what goes on down there, slipping by at 70 mph?) which constitute a major warpage of our social consciousness.

Moreover, automobiles are incredibly dangerous, most because there are a million unskilled, palsied mentalities piloting each million vehicles, running the possibilities of fatal mistakes into the uncountable (I never drive in the far left lane anymore, a sitting duck for the drunken father of five to careen his Bell Gardens pick-up coming through the gossamer chain-link divider), but partly because Detroit builds such obscene eggshell coffins (lousy engine mounts to send it splintering through your shins, or sleek “hard-tops” with no rollbars). As automobiles and freeways beget more of their respective kinds, “improved” automobiles procreate more psychotic drivers who exceed the speed limits, wait until the last moment to brake and change lanes, or four-wheel drift through curves.

“The American motorist thinks of driving as an evil sort of manual labor which is beneath his dignity. Shifting gears is only for poor people and hot-rodders. The affluent simply don’t want to engage in the tedious and difficult task of physically driving an automobile. Most are content just to sit back and relax in their thickly padded seats and drown themselves in the luxury of having nothing to do behind the wheel except curse occasionally at the people who pass them on the right while they’re busy daydreaming in the passing lane. The average motorist, with countless mechanical servants to perform his job for him, has very few mechanical responsibilities behind the wheel. Because he has nothing to do, he also has little to think about, and as a result he can actually go into a semi-trance while he is at the wheel. He has so many gadgets to help him drive that he often delegates to his mechanical servants more driving responsibility than they can possibly handle” (Ronald H. Weiers, Licensed to Kill, New York, 1968, p. 25).

It is nothing less than terrifying that big-time car dealers and pitchmen like Ralph Williams (often on the Tonight show…as a guest), Cal Worthington (who “wrestles” a tiger to get your purchase), Steve and Ronnie Shukin, and Chick Lambert (“my dog Storm”) are pop folk heroes when the conditions in which they purvey their wares should rank them with drug pushers. (The analogy continues: LA has this terrible habit which gets harder to satisfy every day, but which is slowly killing it; the only known cure is cold turkey in Lexington or Idaho; and the pushers obtain their customers as schoolchildren, hooking them for life.) At least the merchant of horse doesn’t cause omnipresent pollution, deplete the natural resources, or kill 60,000 persons annually. Even without this “fanciful” connection, many L.A. car dealers are sent to prison for fraud and related offenses, H. J. Caruso (“he’s the greatest!”) and Joe Carbo (Maywood-Bell Ford) among them.

As the freeways have given us more cars, the cars have given us more freeways; unless you spend every waking hour ulcered or despondent, you must learn to love them, learn the basic lessons of pop that ugly is beautiful, criminal is sophisticated, and that a death rattle is the song of vitality.

Insidious propaganda for freeways is everywhere, even in the head of an unsuspecting English scholar naively supposing the proposed Century Freeway could be a beneficial, cooperative venture between the division of highways and the “community of Watts,” in which “new houses and apartments, emphasizing neighborhoods, would be built for the people dislodged by the freeway” (John B. Rae, The Road and the Car in American Life, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1971, p. 312). (Where? In the rest of crowded Watts where five units on a single-unit lot is common? Or under the new freeway like the store Highway Patrol cars?)

The Automobile Club of Southern California, which most think of as a dispenser of tourist maps and towing services but which is really the pimp link in the highway lobby, puts out glossy editorials complaining that “political planners” have “stripped” mileage from the proposed freeway system, the “backbone” of any “supplemental” systems such as rapid transit, etc. One of their flacks tells a merchants’ meeting that a rapid transit’s reduction of car traffic will be “partially offset by the need to generate more electric power.” (And what generates the power for the cracking plants refining the gas for the cars?) America’s “drive-in” system which owes its existence to a misplaced frontier mentality, capitalist overproduction, and a surplus of land was stillborn in Britain where Malthus obtained early on. Maybe that’s why Banham’s so in love with it, like a Jesuit school student enamored of brothels. But even America and Los Angeles are running out of land, gas, air, and patience.

What we are losing most rapidly is blue sky; the winter postrain mornings are so startling in their infrequent clarity you can rear-end somebody on the Santa Monica Freeway while stupified by the unaccustomed sight of mountains. On an airliner landing at LAX, the Basin looks like coffee-stained carpet with a few pointy rocks dropped on top. On vintage days a terrible pang in the lungs awaits you at the bottom of a three-quarters inhale. And we piss in other people’s wells, too: Riverside, 60 miles east and never having done nothin’ to nobody, had 71 days of smog alerts last year. (A faint blessing, however, is smog’s unselective social justice: Beverly Hills and San Marino, homes of the managerial class who never reside near their belching industries, are two of the biggest smog-traps.)

Smog, whose name comes from Pittsburgh and whose first spectacular in L.A. was the famous “Black Tuesday” in 1943 (they thought it was backyard trash burning) has been a Los Angeles highlight for a generation:

“The great increase in industry has created a smog problem which makes Angelenos cry, figuratively and physically. Lying in a bowl between mountains and sea, L.A. has a climatic situation found only in a few places in the world. Fuel oil and gas create practically no smoke, but industry creates many fumes, and when there is no wind a heavier stratum of air above keeps fumes from traffic, industry, trash disposal or anything else from rising, and the mountains keep them from blowing away. Experts are working and millions are being spent to correct the situation but smog is still the city’s greatest irritation…often one cannot see the City Hall from six blocks away. Often there is a stinging mist which makes Angelenos rub their eyes and squint and swear – and makes photographers rival Niobe” (Lee Shippey, The Los Angeles Book, Boston, 1950, p. 29).

The chemical constituents of this deathly soup are carbon monoxide, ozone (caused by the sun’s cooking the whole mess), oxides of nitrogen, and side orders of such poisons as lead (from gas’s ethyl compound), asbestos (vaporized from tires), and good ol’ putrid sulfur. Add to this the following tidbits: 1) every native within striking distance of puberty has emphysema; 2) each car, if you consider fresh air to dilute pollutants, requires as much air to “breathe” as the city’s entire population; 3) the power companies’ big stinkpots are on the beach, upwind from the people; 4) the Air Pollution Control Board rubber-stamps “variances” for practically any industry (Kaiser steel’s yearly payoff is about $12,000 for a hundred); 5) the “Coordinating Research Council” in Washington handling smog studies is run by a Standard Oil exec; and 6) mass fatalities are predicted for Long Beach in the 1975-76 winter. Reyner Banham, however, sees a silver lining:

“On what is regarded as a normally clear day in London, one cannot see as far through the atmosphere as on some officially smoggy days I have experienced in Los Angeles. Furthermore, the photochemical irritants in the smog…can be extremely unpleasant indeed in high concentrations, but for the concentration to be high enough to make the corners of my eyes itch painfully is rare in my personal experience, and at no time does the smog contain levels of soot, grit, and corroding sulfur compounds that are still common in the atmospheres of older American and European cities” (pp. 215–216).

That smog does corrode (it rots rubber and kills plants) is a small mistake compared to Banham’s staggering Pollyanna lack of observation; he must have studied L.A. through a telescope from Santa Barbara. Smog, the direct offspring of our automotive “liberty” (80% is car exhaust), gets everybody (when the Santana winds clear out the inland valleys, the beachy “south bay” suffers the alerts). There are no hiding places, for rich or poor, black, brown or white, boss or flunky, and you’d think we’d learn, but the you-scratch-mine-I’lI-scratch-yours relationship between city and county government and the power companies and the car / highway combine continues practically unabated.

Corruption by deed or default isn’t just historical anecdote in L.A., it’s part and parcel of the city’s style, from the time Collis P. Huntington’s Southern Pacific Railroad sewed up all the land around what he thought was to be L.A.’s Santa Monica harbor (the Santa Fe out-dirtied him and strong-armed Congress into appropriating $3,000,000 to build an artificial harbor way down in San Pedro, along their routes and Phineas Banning’s heavily promoted land), to the time the Board of Trustees of the L.A. County Museum of Art (some of whom sit on the University of California’s high councils as well as the directorates of each other’s companies) forced director Ric Brown to abandon Mies van der Rohe as the scheduled architect and settle for archi-businessman William Pereira (who does University of California campi, wholesale) and a triple-threat monument to mediocrity. The queen of them all, however, was the infamous rape of the Owens Valley early in the century; a real estate syndicate holding vast arid acreage in the San Fernando Valley sought to make a killing by turning it into a populated suburb. The solution lay in bringing in drinking water from the agricultural Owens Valley (itself hard-won from the desert), but the federal government wouldn’t bankroll an aqueduct (the rights to which were got by L.A.’s mayor secretly buying up riparian land in the Owens Valley, city engineers going out in the night and dynamiting farmers’ irrigation dikes, etc.) unless it terminated in Los Angeles proper. So, Mohammed not being able to go to the mountain… the city of Los Angeles in rank collusion with a few scheming realtors (nothing ever changes) annexed the far, empty reaches of the San Fernando Valley, drained all the water (although with a reservoir, sharing would have been feasible) from the Owens Valley, and left it for dead.

“Los Angeles gets its water by reason of one of the costliest, crookedest, most unscrupulous deals ever perpetrated, plus one of the greatest pieces of engineering folly ever heard of. Owens Valley is there for anyone to see. The City of the Angels moved through this valley like a devastating plague. It was ruthless, stupid, ruel and crooked. It deliberately ruined the Owens Valley. It stole the water of the Owens River. It drove the people of the Owens Valley from their home, a home which they had built form the desert. It turned a rich, reclaimed agricultural section of a thousand square miles back into primitive desert. For no sound reason, for no sane reason, it destroyed a helpless agricultural section and a dozen towns. It was an obscene enterprise from beginning to end” (Morrow Mayo, Los Angeles, New York, 1933, pp. 245–246).

Los Angeles sits on a boneyard of smelly real estate deals, crooked rights-of-way, the L.A. Times Mirror empire, “industrial freedom” (antiunion gangsterism), freeway sellouts, and aerospace bailouts (Lockheed, a mismanaged defense giant which blue six billion tax dollars on the CSA white elephant, was kept afloat by our own local R. M. Nixon and a $250,000,000 public loan guarantee). Twenty-two years ago it was optimistically written:

“The $100,000,000 grant for slum clearance which the city has secured from the federal government should turn Chavez Ravine and other breeding places for delinquency and disease into pleasant, sanitary and well-serviced areas for low-income families, and Skid Row and other disreputable areas are on the way out” (Shippey, p. 104).

Seven years later when there was still no public housing on the land Mayor Norris Poulsen retrieved it from the federal government and sold it to Walter O’Malley for a pittance on the condition that it be “recreationally developed” in addition to gouging out Dodger Stadium and a huge parking lot on its premises. The last Mexican shanty-dwellers were forcibly evicted at point of shotgun. Shortly before opening day it was discovered that there were no public drinking fountains in the stadium (Cokes cost a quarter and a beer a half a buck); there still isn’t much park stuff up there. Walter O’Malley is now reported to be one of the largest landowners in the state.

Now we’ve got Sam Yorty, a frozen-smile, monotone, cardboard “presidential candidate” always conveniently absent (as during the Watts riot) on a trade mission to one of our “sister cities,” and a police chief who advocates instant on-site “trials” for hijackers and finds communist “dupes” in every peace demonstration. The city council is still a low-comedy asylum of petty dickerers, patronizing “Oreo” blacks, fake, overage collegiate liberals, and a brace of the usual ossified Masonic lodge cadavers; the L.A. County Board of Supervisors is even worse, the smallest group of the dumbest men to have jurisdiction over such a large area in captivity—the Dorn v. Ed Keinholz fracas (Back Seat Dodge, a sexual/social tableau which was censored at the County Museum, and the retaliatory bumper sticker born: “Dorn is a four-letter word,” etc.) indicative of its heights. It makes John V. Lindsay look like Metternich.

In a physical and political milieu like this you wouldn’t expect L.A. to have much culture and it doesn’t. Myriad struggling and/or underground dance recitals, performances, little theater, and concerts take place, but strictly hit-and-run; large emporiums like the Music Center downtown are hotbeds of light opera, broadway musicals, and vanilla comedies. The art world of the La Cienega/Venice/Irvine axis compares reasonably with uptown/SoHo except in numbers, but it’s even more piddling in real-world political punch. (That the late ‘60s-to-now artists have gradually eschewed object art as too “irrelevant” and bourgeoisie in favor of something which has thus far only managed to politically reform a few curators is the subject for another essay.)

The Spanish-speaking culture is more or less restricted to the barrio, due to a history of gringos marrying into the Mexican wealth and then trampling it with Anglo hardware, like freeways. The proximity of the studios who’ve almost by accident produced a few good movies (Citizen Kane, The Maltese Falcon, Singin’ in the Rain, High Noon, and Five Easy Pieces) has generated a show-biz-oriented, quick-hit “wow,” ephemeral esthetic, effectively ruling out quality except for deliberately underground art or novels about decadence (Nathaniel West, Raymond Chandler, Ross MacDonald, Gavin Lambert, Aldous Huxley, Evelyn Waugh, Christopher Isherwood, and Joan Didion). The “fine art” end of things is dominated by a few interlocking-directorate corporate families (Chandler, Simon, Carter, Ahmanson, etc.), all with gargantuan nouveau-riche tastes for pretentiousness (compare the L.A. County and Pasadena art museums to the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, or the Whitney), and a red-carpet “scene.”

It’s amazing that for all its newness, L.A.’s architecture generally stinks; the good stuff is limited to residences, creaking Victorian houses, the small buildings of European expatriates like Neutra, a few old buildings like the Bradbury and the L.A. Public Library, or, painfully, free-way architecture. The worst offenses arrive courtesy of the Pereira-Beckett-Gruen bag of ersatz “planning” and styrene elegance; that’s why Stone’s Perpetual Savings Building, a B-plus at best, stands out in spite of its recessed placement among all the multimillion-dollar garbage on Wilshire Boulevard. Just look at the monstrous public buildings: Pauley Pavillion, the Sports Arena, the “fabulous” Forum, the County Art Museum, the new courthouses, the LAX restaurant, a dozen new glass towers downtown, the gateway to Westwood, Sunset and Vine, glamorous “entire city” shopping centers, and on and on and on. Currently what passes for “planning” (meaning “you can still move away from the blacks and Chicanos and simultaneously salve your consciences about saving poplar trees”) are affluent tracts (“Harbor Shores Estates,” “Rancho del Vista,” or similar horseshit) and covered-mall shopping centers “ecologically” carving up more virgin territory (especially now that the Irvine Ranch has sold out). Although what Banham touts as a wonderful disowning of the old “downtown” concept has ruined the suburbs, not even that respite is left us, for downtown is springing back to rip-off life with such construction as Atlantic-Richfield Plaza, Arco’s new corporate headquarters.

Sure, New York and Chicago are worse, pound for pound. But the tragedy of Los Angeles is that just enough of the jasminelike scent of possibility lingers to render a blurry, fugitive sense of what it might be; an occasional sunset, glimpse of a jackrabbit, a group of kids hitting the surf, or a mixed bunch of hard-hats lunching by a pick-up remind you of what a grand natural place this is, if weren’t for the big money-lenders, franchise operators, highway lobby, culture moguls, and reactionary politicians. What we obviously require, short of a Revolution, is the kind of hardcore planning Banham despises; we need to get the cars off the freeways and replace them with thousands of free propane buses (which would probably cost less than building more freeways, patroling them, and picking up after crashes); we need to discourage the business of every single-unit dwelling facing a spacious street across a useless front yard; we need to quit building shopping centers with parking lots the size of Monaco; we need to quit selling dune buggies arid electric combs so SoCal Edison and Union Oil won’t have their excuses to duplicate Carthage in Redondo Beach; we need…we need…

“If everybody householded land in such patio or atrium houses, Los Angeles would have 40% of its size, of its pole lines, and endless expensive roads. It might have half its traffic to wreck nerves and half the exhaust gases to pollute the blue sky and breathing lungs” (Neutra, p. 266).

Why can’t we? The immediate reason is physical: you’d have to undo 30 years of corruption and lousy design; the second reason is political: everybody’s got his weenie in the ringer to some extent (I own a house and two cars and I’m a liberal). But the third reason falls within my purview as an art critic and is, I think, largely undocumented: the chickens of pop coming home to roost. By pop I don’t mean just Lichtenstein and Oldenburg, but a pervasive, 1984-ish, bad-is-good visceral misconception invading our pores since the mid-’50s, maybe earlier. The trash of our urban environment is so overwhelming that the choices seem to narrow, at least psychically, to suicide or capitulation; so the 999 of every 1,000 who don’t blow it off begin surrendering tiny strands of moral fiber: novelty catalogue drawing isn’t so bad if you look at it right; Cadillac fins and donut whitewalls are really pretty groovy; professional football is obscene, but some of the heaviest people super-dig it so why don’t you; sparkle-front apartments all in a row make a nifty limited edition; a bullet through the eyeball in 70 mm color bends heads the wrong way but it’s O.K. if you’re an ultra-violence Peckinpah cultist; a seedy stucco “Strip” with juice-sucking neon and carny pitchmen is “electrographic, relevant” architecture. You do enough of these numbers and pretty soon your whole sense of social utility has crumbled; or if you’re an architecture critic jetting in from Lon- don with visions of Hockney and Blake (Peter, that is) dancing in your head, you’ve put it out to pasture long ago:

“At its most extreme it can become a naively nonchalant reliance on a technology that may not quite exist yet. But that, by comparison with the general body of official Western culture at the moment, increasingly given over to facile, evasive, and self-regarding pessimism, can be a very refreshing attitude to encounter… The tradition of mobility that brought people here, sustained by the frenzy of internal motion ever since, and combined with the visible fact that most of the land is covered only thinly with very flimsy buildings, creates a feeling—illusory or not—that you can still produce results by bestirring yourself. Unlike older cities back east—New York, Boston, London, Paris—where warring pressure groups cannot get out of one another’s hair because they are pressed together in a sacred labyrinth of cultural monuments and real-estate values, L.A. has room to swing the proverbial cat, flatten a few card-houses in the process, and clear the ground for improvements that the conventional type of metropolis, can no longer contemplate” (pp. 242–243).

Obviously it’s quite a different business to appreciate those flimsy buildings for the RIBA Journal than it is to live in them, but Banham presses on. One hundred pages after a raving paean to a miscarriage called the Tahitian Village restaurant in Bellflower (“strikingly and loveably ridiculous,” p. 124) comes the big, pat-on-thine-own-back finish:

“On the other hand, there are many who do not wish to read the book, and would like to prevent others from doing so; they have soundly-based fears about what might happen if the secrets of the Southern California metropolis were too profanely opened and made plain. Los Angeles threatens the intellectual repose and professional livelihood of many architects, planners, and environmentalists because it breaks the rules of urban design that they promulgate in works and writings and teach to their students. In so far as L.A. performs the function of a great city, in terms of size, cosmopolitan style, creative energy, international influence, distinctive way of life and corporate personality…to the extent that L.A. has these qualities, then to that same extent all the most admired theorists of the present century, from the Futurists and le Corbusier to Jane Jacobs and Sibyl Moholy-Nagy, have been wrong” (p. 236).

Charitable to even the grossest perversions, I can partially sympathize with Banham’s hamburger-stand fetish; England is a country steeped in a tradition of aristocratic, Chippendale quality supplanted by a gently socialist concern for the “greater good” on an overpopulated island. I imagine he’s had it up to here with civil servants, village greens, planned “new towns,” welfare state housing projects, committee hearings, the old-boy network, tweed suits, and cool overcast days. And if he wanted to run out and paint pictures of the Roller Derby or the Stones it’d be O.K. because it’d be innocuous - and Pop art does teach us “new ways of perceiving” Brillo boxes and the like. But when you get into architecture it’s big casino, real people’s real lives, and the Pop artiness of Banham and Venturi greases the slide into the moneymen’s pockets…and here we go with another strangling round of MacDonald’s, freeways, and confectioners’ culture palaces. When the frail last defenses of the progressive architect are bartered on the counter of hipness, when an ostensibly perceptive specialist takes a look at this obvious dung-heap and pronounces it a groove, then the capitalist quick-buck juggernaut will all the more quickly kill off the green that’s left. The style will continue bright and trashy; the air and water will get worse and Riverside and Albuquerque will die with us. L.A. needs the cleansing of a great disaster or the founding of a barricaded commune, but it won’t get it. Instead it gets garish pop deliriums like this:

“The illegitimate children of our crazy ideas will be spawned east of Ambrose Light Ship at dawn in 1982, then beyond to Odessa and Hong Kong. Shortly thereafter, we will meet our mirror image, semi-hysterical, and fecund as a swarmed bee colony, Japan, shouting American baseball cries and rising with Industrial Revolts out of the Orient Sea” (Ray Bradbury, “Los Angeles is the Best Place in America,” Esquire, October, 1972, p. 174).

Ray Bradbury is hard to figure out, but the trouble with Reyner Banham is that the fashionable sonofabitch doesn’t have to live here.

—Peter Plagens

(Originally published in Artforum, December 1972, pp. 67–76.)