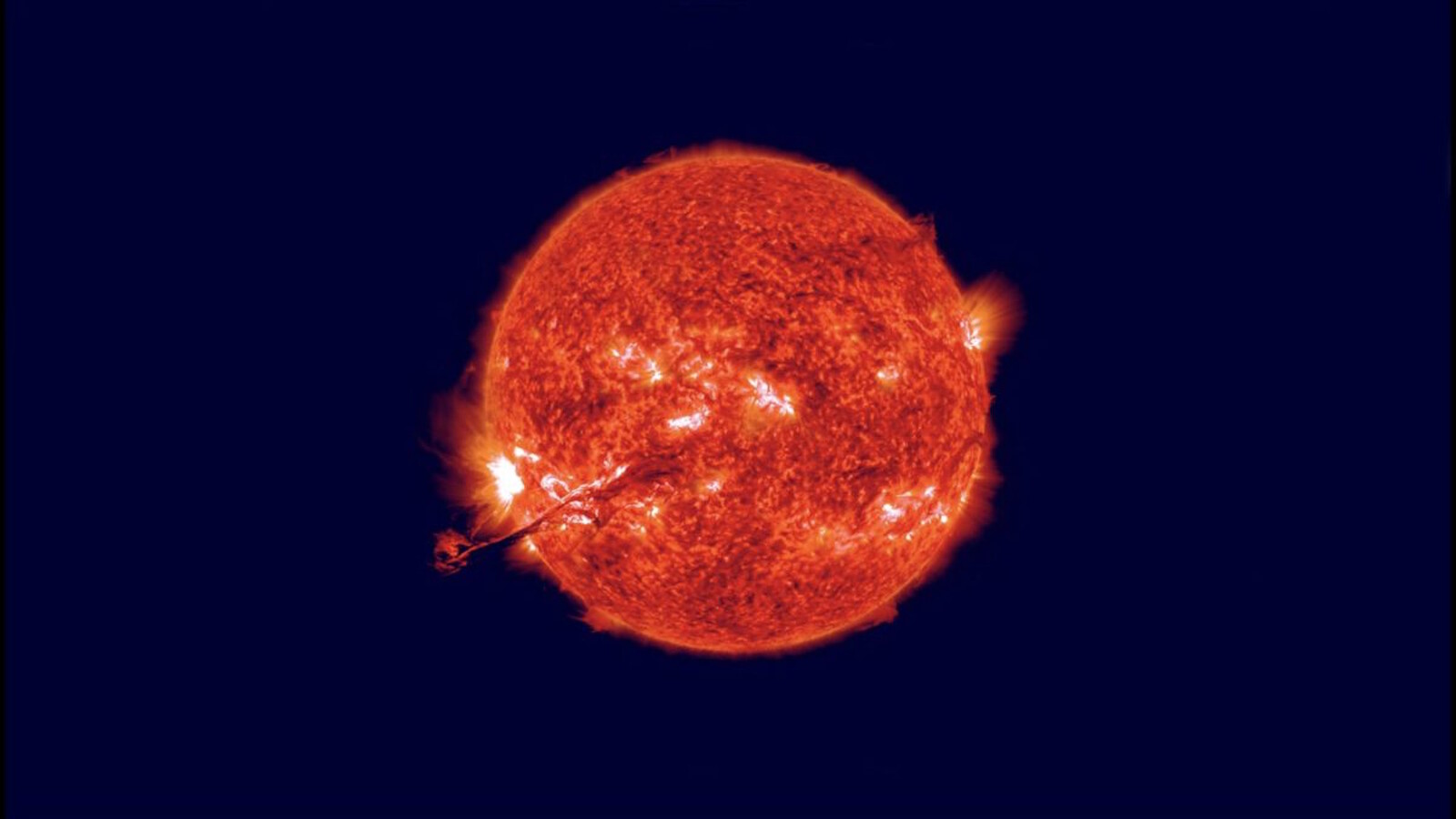

In these days of confinement, I’ve turned to classical Hollywood for comfort. Revisiting Ernst Lubitsch’s sublime Design for Living (1933), I came across a line worth noting down: “Delicacy, as the philosophers point out, is the banana peel under the feet of truth.” If that is so, eager to avoid slipping, I’ll come out and say it from the start: the huge number of moving image artworks that have been made available to stream online in the past few months stresses me out.

With cinemas and art spaces around the world suddenly subject to indefinite closure, film festivals have rushed to organize virtual editions, while institutions and commercial galleries have anxiously maintained their visibility by initiating online programs, often presenting changing selections on a time-limited basis. Just as the news appeared that Julia Stoschek, one of the premier private collectors of the moving image, will likely shutter her Berlin space in 2022, she made more than 68 works—some 15 hours of material—available on her website.

The online display of moving image artworks is nothing new. The curated platform Vdrome.org, which shows a single work for a two-week duration, began in 2013; unauthorized forms of dissemination have an even longer history, with the addition of video files to Kenneth Goldsmith’s site UbuWeb from 2002 onward standing as a notable milestone. But it has taken a global pandemic to open the floodgates. While it’s easy to crack jokes about the sad “viewing rooms” of online art fairs, the moving image—by virtue of a relationship to reproducibility and materiality very different from that of most other mediums—seems to be able to migrate online with ease. Even the Guardian proclaimed that “video art” is “flourish[ing] in lockdown,” “finding a new audience hungry for culture that is accessible, original and bizarre.”1

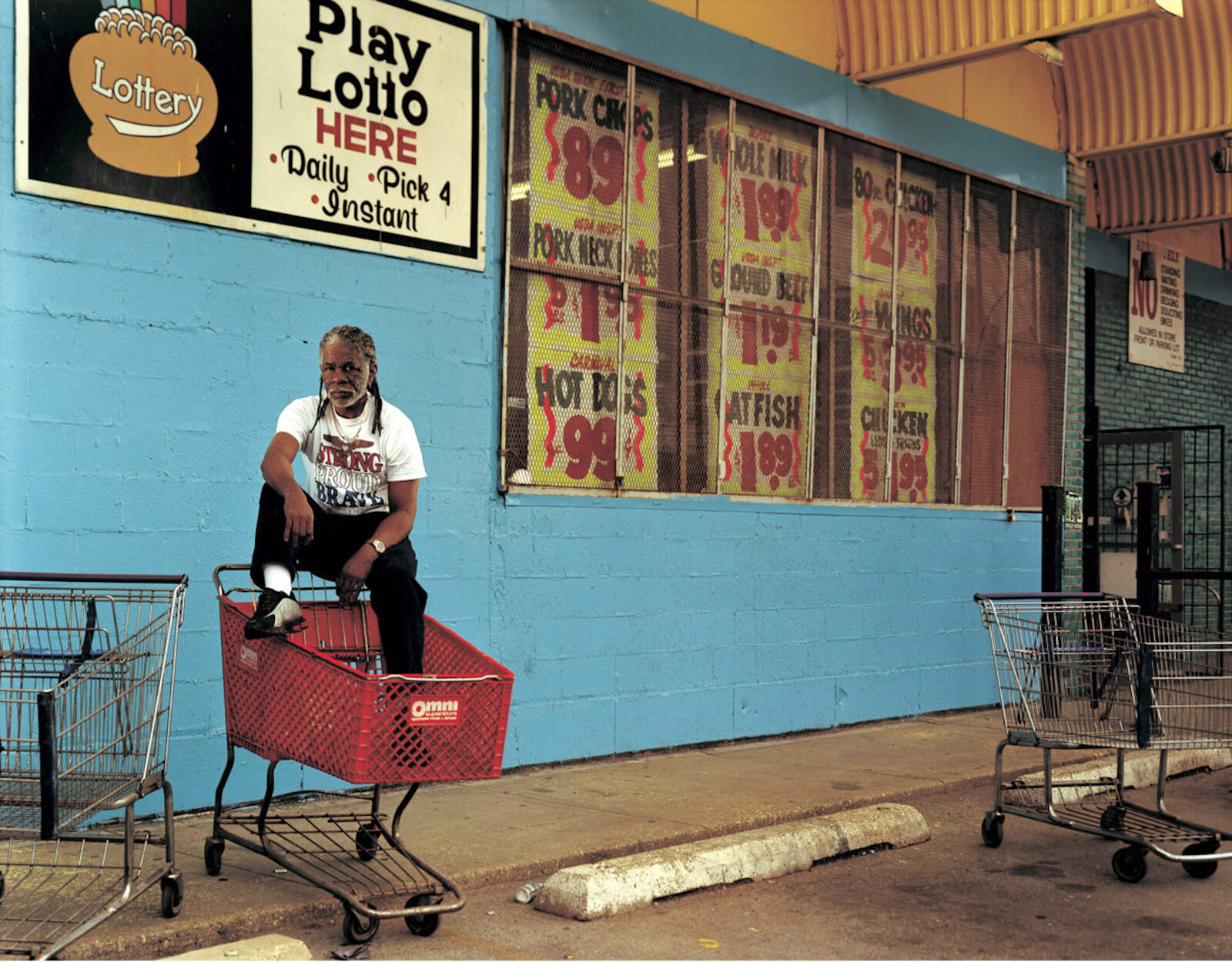

Explaining the decision to present her collection online, Stoschek refers to the history of the forms she favors: “In their beginnings film and video art were profoundly democratic media, without limits or restrictions for artists and viewers.”2 Indeed, for many artists working in the 1960s and ’70s, part of the appeal of the moving image was that it escaped the tyranny of rarity. In a catalogue essay accompanying a 2012 exhibition of the same name, which he curated at the Fondazione Prada, Venice, the late Germano Celant proclaimed the desire for the unlimited fabrication and democratized distribution of art objects a “small utopia,” proposing that it constitutes an important counterhistory of twentieth-century art. For Celant, the apotheosis of this utopia was found in the vogue for multiples of the late 1950s and ’60s. But there is ample evidence to support the claim that it might rather be found in the distribution infrastructures that developed shortly thereafter around the fledgling fields of artists’ film and video, bright with the hope of broad circulation. The embrace of digital dissemination reignites the promise of this small utopia—one that, in authorized channels at least, had withered somewhat from the 1990s onwards, as the artificial rarity of the limited-edition model of sale made the moving image more amenable to an art market predicated on scarcity.

Open access to incredible artworks from the comfort of home, far from the metropolitan centers of the art world, without recourse to piracy: it sounds like a dream. I have returned to my favorites, sinking into the perfect three minutes of Bruce Baillie’s All My Life (1966), presented as part of a shorts program by the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. I eagerly followed the rotating rarities, old and new, posted biweekly by Berlin’s Arsenal–Institut für Film und Videokunst in what is, to my mind at least, the best freely available streaming selection the internet has to offer. I watched shorts by Sarah Maldoror ahead of a Zoom event organized by the publication Another Gaze, memorializing the pathbreaking filmmaker who passed away, aged 90, on April 13 from complications related to Covid-19. I dipped into the international competition at the Oberhausen International Short Film Festival, and checked out Corrientes, a recently launched platform devoted to Latin American artists.

Just when I thought I was up to speed with it all, I received an email from London’s Kate MacGarry Gallery, alerting me that a new video by the formidable John Smith was premiering on Instagram and would be available for one week. I clicked immediately. In the three-minute Twice (2020), Smith stands in front of a mirror, singing “Happy Birthday” in a minor key, like a funeral dirge, twice, as he washes his hands. Cut to Boris Johnson advising the public to contain the spread of coronavirus by doing exactly this—well, minus the minor key. Otherwise, the UK prime minister says, “for the vast majority of people in this country, we should be going about our business as usual.” Smith ends with a title card that twists the knife: “Made in London during the sixth week of the lockdown, when Britain’s COVID-19 related death toll reached 25,000.” With a tremendous economy of means, Smith marshals his dry humor in the service of outrage at the incompetence and cruelty of a Conservative government that has decimated the capacities of the NHS and other social services throughout a decade of austerity, now as ever ruling in the interests of the rich, the rest of the country—and particularly the most vulnerable—be damned. For Twice, so concise and timely, online exhibition was a perfect fit.

The positives of this new regime, in theory and practice, are clear. So why does it stress me out? The seemingly endless barrage of links induces a feeling of glut, certainly. But beyond my sense that there are too many great films and too little time, significant issues of presentation exist. Long after the internet was able to support streaming works in high definition, allaying concerns about picture quality and turning Hito Steyerl’s “poor image”3 into an historical concept, and even after it became clear that putting editioned works online would have no real impact on their monetary value, many artists and institutions refrained from doing so. This spring’s crisis has provided the push some needed to finally get with the digital program, but the concerns that made them hesitant to stream video in the old world persist in our new one—and with good reason. It’s just that now there is more willingness to compromise.

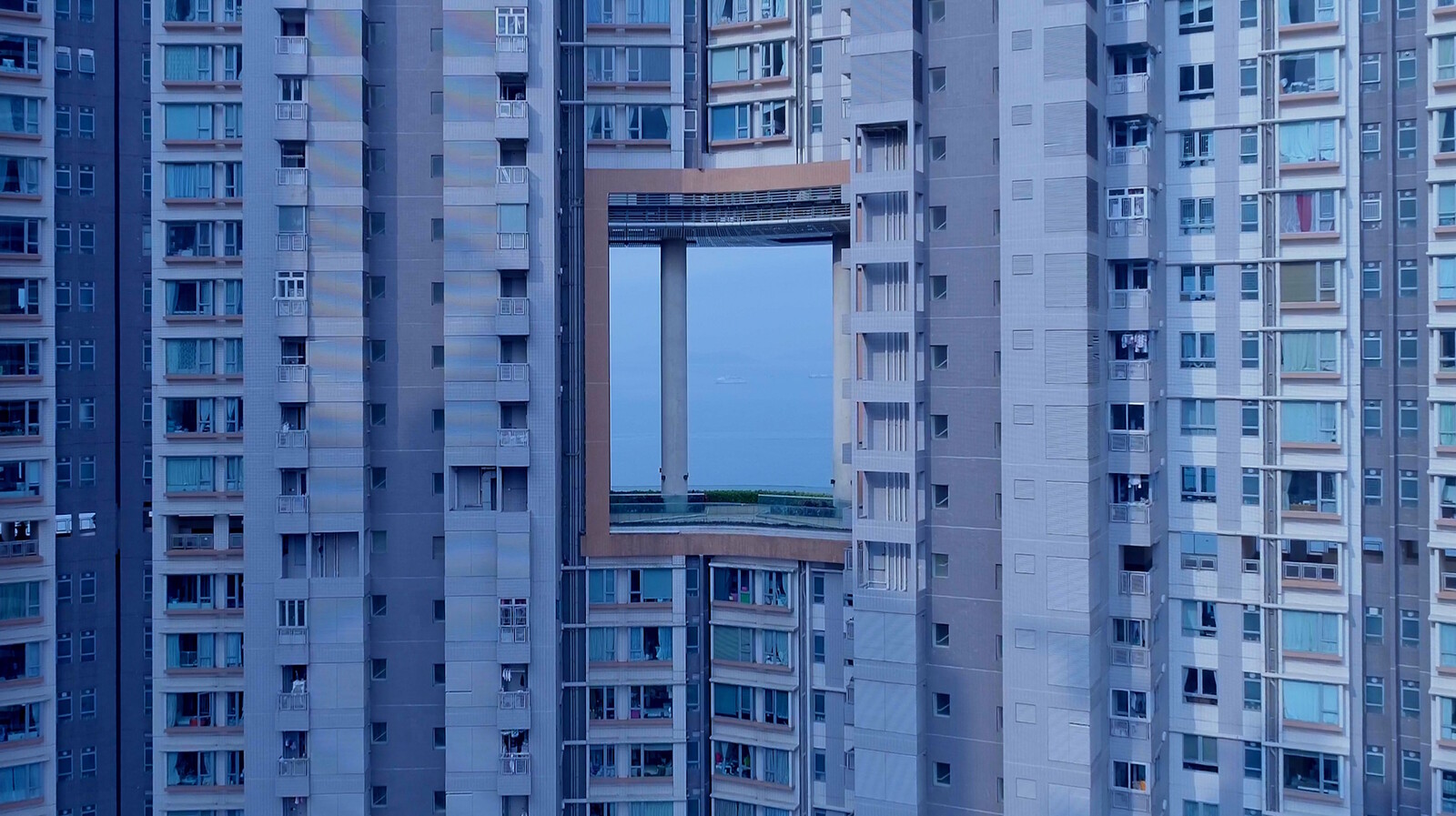

The word “streaming” itself offers a hint at the problem: presented online, moving-image artworks risk absorption into a ceaseless cascade of undifferentiated “content.” The short running-times adopted by many artists can make such works well-suited to the fast flow of digital information, but it equally means they are more likely than, say, a feature film to be flattened as they compete for attention alongside pop-up notifications, TikToks, advertisements, and infographics mapping infection rates. Viewed on the internet, the specificities of the originally intended display context fall away, whether it is the scale and positioning of the screen, the calibration of light, or the experience of collective reception. These losses hold true for all moving images made for public presentation—not for nothing did the film critic A.S. Hamrah, who writes mostly about mainstream cinema, title his 2018 book The Earth Dies Streaming—but they are especially acute for artists’ film and video, a field of practice that depends extensively on non-standardized orchestrations of time and space that can fail to translate well to a laptop screen. Some works will fare worse than others when making this leap, yet what is always at stake is nothing less than the collapse of a certain kind of aesthetic experience—one that it is neither nostalgic nor elitist to cherish.

There is also the matter of the economics behind it all. Here, the situation differs significantly and unsurprisingly from commercial cinema and its sometimes lucrative licensing agreements. In 1973, Hollis Frampton wrote a letter to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, responding to their offer of a retrospective, for which he would not be paid. Filmmakers, he wrote, “cannot continue on love and honor alone.” Unfortunately, not enough has changed in the almost fifty years that have elapsed. While there are thankfully some exceptions, too often artists receive payment for works exhibited online in that phoney currency, “visibility.” What is free to the viewer comes at a price to them, and at a time of increased precarity.

Is the current turn to streaming an emergency measure, a blip to be recalled as the great flood of spring 2020, or is it here to stay? I don’t imagine anyone will reproach film festivals for abandoning online programming as soon as is safely possible. As for galleries and institutions, the situation is more complicated. If their forays into streaming have truly been undertaken out of a commitment to democratization, they might continue even after physical spaces have re-opened. Were this to occur, I would hope that it would be with a commitment to properly remunerating artists and curators, an acknowledgement that less is more, and an eye to selecting the works most amenable to the online context and presenting them on platforms designed to mitigate its perceptual poverty.

Stoschek has declared that she will eventually make all 860 works in her collection freely available online. Doing so will pose some challenges. Many include substantial installation components and/or multiple screens. Negotiations will be necessary with each artist, and possibly also with other collections holding editions of the same work, to secure permission. Piracy is inevitable. Most authorized streaming initiatives have thus far depended on limited viewing windows to maintain some semblance of scarcity; Stoschek’s intention seems to be to make her collection available in perpetuity. As someone who teaches the history of moving image art, and who has often lamented the lack of works available for students to see in class, I am excited about the possibilities of this resource. But I also worry that it—like the streaming paradigm more generally—blurs the crucial distinction between the presentation format intended as primary (the work as it was made to be seen) and secondary contexts that are useful proxies but ultimately inferior. To say it’s like the distinction between a painting and a postcard of that painting isn’t exactly correct, but it gets the idea across. Contrary to what Stoschek’s press release suggests, it is patently not the case that, “due to the audiovisual component, time-based media art is predestined for viewing on a computer, tablet, or smartphone.” Some works are made with just such devices in mind, but most are not.

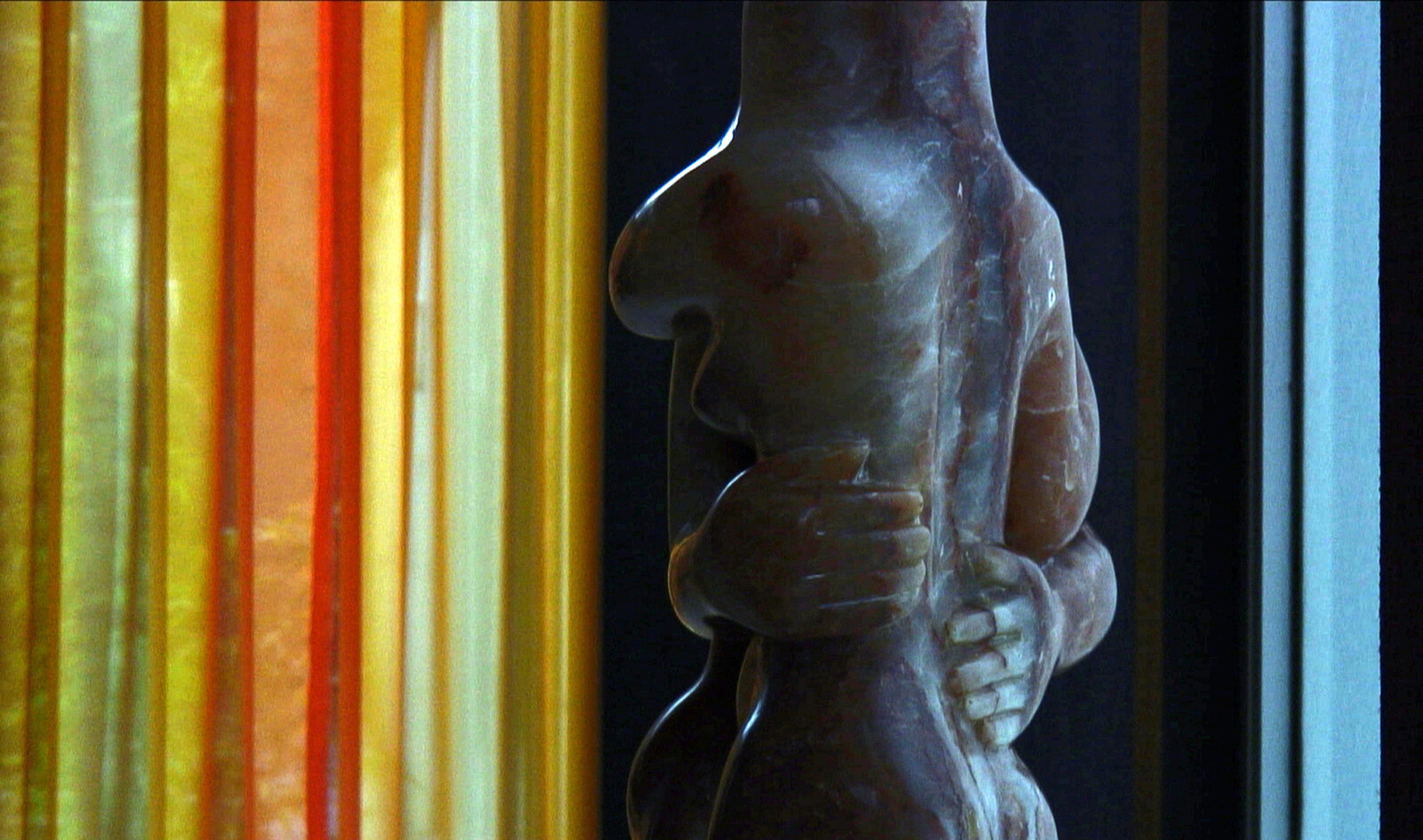

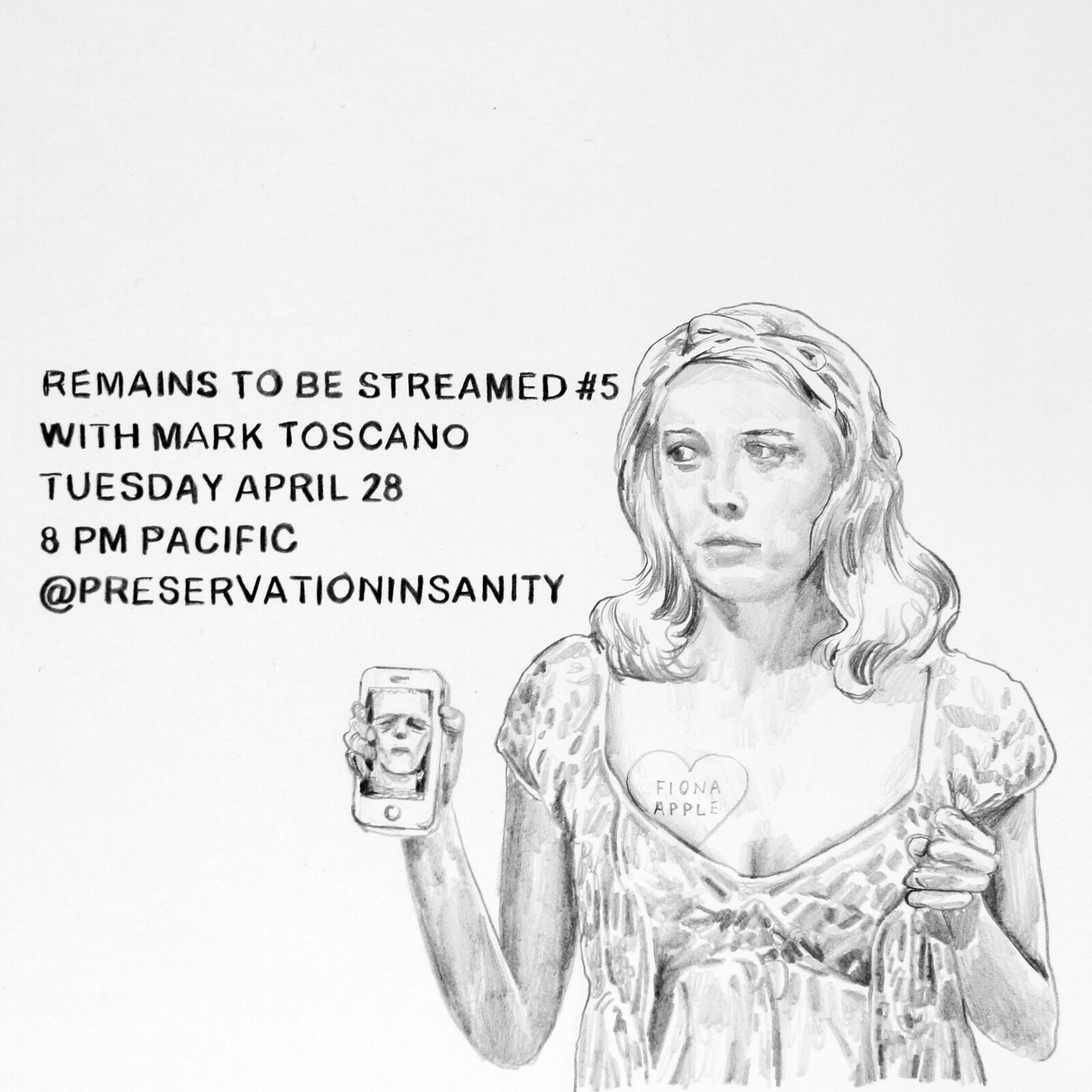

The almost comical acknowledgement of the gap between primary and secondary formats is one of the things I love about the most original example of streaming I have come across during my time indoors: the broadcast “Remains to be Streamed” from the @preservationinsanity Instagram account, which has been happening weekly on Tuesdays at 8 p.m. Pacific. (Thankfully for those of us in other time zones, it remains available to view for a few days thereafter.) It is the pet project of Mark Toscano, an archivist at the Academy Film Archive in Los Angeles, known for his work on experimental film. No longer able to put on his “Remains to be Seen” screenings at the Echo Park Film Center, Toscano took to hosting a livestream during which he projects 16mm films in his apartment, generally prints produced as part of the restoration process. On the morning of May 13, my tiny iPhone screen showed me the shadow of rare works by Barbara Hammer and Chris Langdon, their soundtracks blending with the clattering of the projector. Between films, Toscano chatted affably, offering details and anecdotes, responding to audience comments. It was an emphatically mediated experience, a strange meeting of photochemical materiality and the data streams of social media, that made no attempt to substitute for theatrical projection. It was a matter, as all the best screenings are, of passion and community. I loved its liveness and its lack; I loved how much it made me look forward to seeing those same films in the cinema, with friends.

Lanre Bakare, “‘It’s great if you’re bored with Netflix’: video art flourishes in lockdown,” the Guardian (May 4, 2020) theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/may/04/its-great-if-youre-bored-with-netflix-video-art-flourishes-in-lockdown.