Nostalgia was the prevailing feeling as I approached Frieze New York’s new home at The Shed in Hudson Yards. I wasn’t around when the piers were a queer hub of sex and solidarity, but I remember the East River breeze on the ferry to Randall’s Island on previous visits to the fair, and a time before Thomas Heatherwick’s (indefinitely closed) eyesore The Vessel. Frieze’s pandemic-enforced change in venue brings into sharp relief the disparity between the neighborhood’s new occupiers—business-casual millennials; more recently those getting their vaccines at the nearby Javits Center; and, now, fair-goers—and the legendary stories that haunt the crumbling docks. It was nonetheless hard not to miss the old spectacle of the fair, which has been replaced by a new and more muted tone.

In place of the gigantic sculptures that guarded the vast fair tent in its previous location, visitors to The Shed find a series of more modest flower boxes. The Acute Art “augmented reality” app transforms them, via your phone screen, into Cao Fei’s RMB City AR (2020), a virtual rendering of an exploding, dystopian city. Stationed outside the entrance, the phone-activated work starts the chain of “camera moments” that stretches into the booths inside, 60 of which (representing a roughly 60% drop in the previous number of exhibitors) are spread across The Shed’s three floors in a variety of configurations. With the forced absence of stalwart international galleries from London’s Victoria Miro to São Paulo’s Galeria Vermelho, low ceilings, and a slower pace—which might be attributed to the new social awkwardness in crowds—this edition of the fair is operating on a reduced scale that, previous to the pandemic, would be more typical of a satellite.

Central to this year’s edition is a fair-wide interpretation of the Vision & Justice Project, which extends to new commissions and online events. An initiative launched by the Harvard professor and art historian Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, the project reconsiders the role of art—and visual representation more broadly—in changing the nation’s narrative of race and civic responsibility. For Lewis, the “colliding catastrophes” of the pandemic, and the racial and structural inequalities that it has further exposed, have added renewed urgency to these issues. In an email to me, she described the work as questioning “how American society expanded its notion of who is a citizen, who counts and who belongs.” Whether a commercial art fair offers an effective platform to respond to such questions is up for debate, and it’s a heavy burden to place on, among other things, a new commission by Carrie Mae Weems that greets the visitors at the first-floor entrance. Comprising a set of massive collages, the vinyl work, titled And then, The Rise (2021), celebrates those involved with the project since its inception—such as Thelma Golden, Claudia Rankine, and LaToya Ruby Frazier—with a series of individual book covers.

As might be expected in a year when dealers need to make sales and collectors are emerging from months in front of screens, painting predominates. Highlights include Dominic Chambers’s contemplative figures at Lehmann Maupin and, at P.P.O.W., David Wojnarowicz’s The Boys Go Off to War (1983), an account of the West Side piers: in the left-hand panel, two men are painted over a map; the right shows two animal carcasses. The work’s frank depiction of sexuality and death feels particularly striking within the sterile confines of the fair. When I meet her on the floor, Rebecca Siegel, Frieze’s Director of Americas and Content, suggests that the tactility of painting may have something to do with its current appeal: “I am not surprised the first foray back into a physical space comes with works that require a closer look.” Cristina Canale’s fluid portraits of women at Nara Roesler, which approach abstraction in their hazy open-endedness, are one example, while WangShui’s aluminum honeycomb paintings at Company Gallery combine the mundane with the sublime: paintings of cars and pillows complicated by my own reflections on the glossy surface.

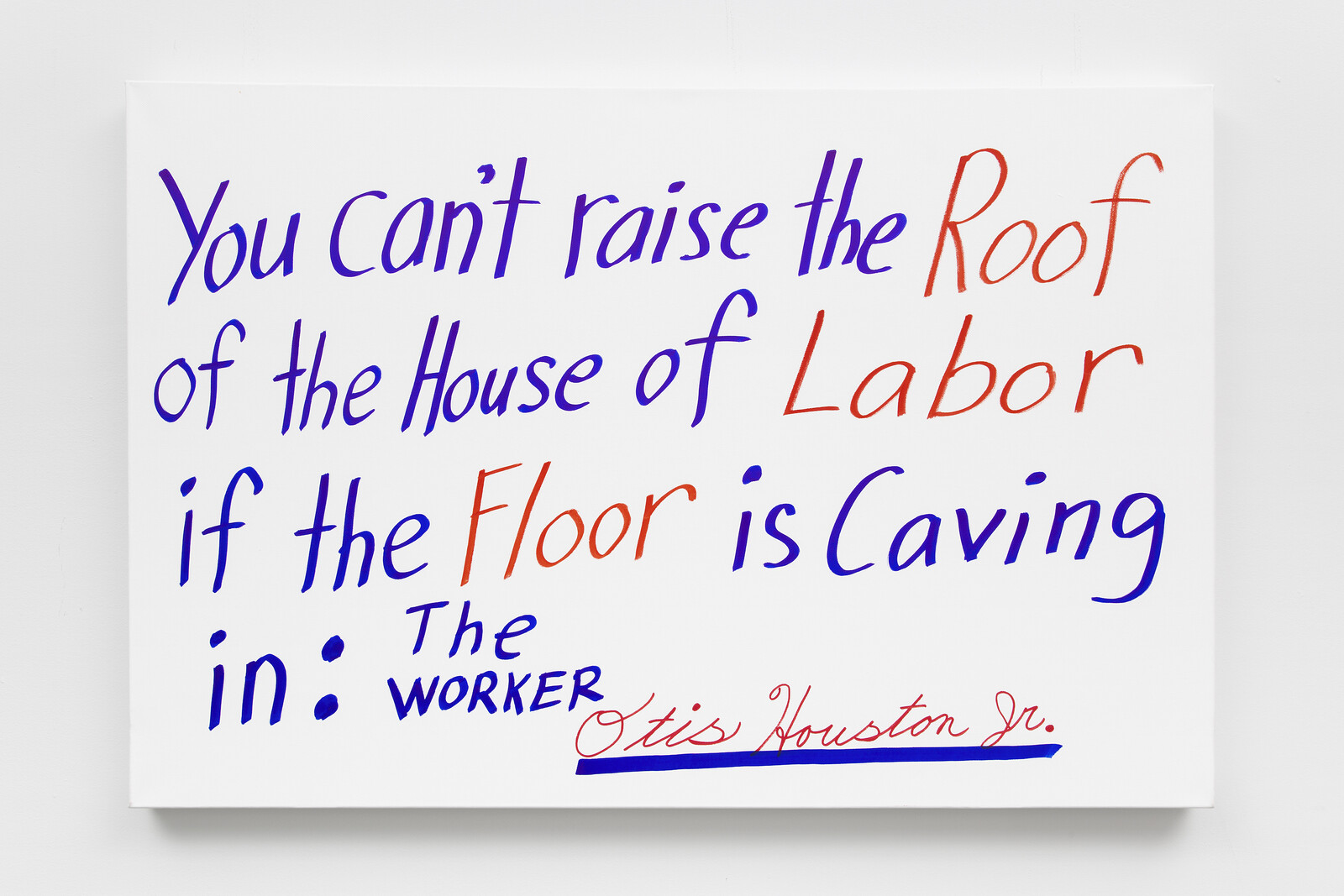

At Gordon Robichaux, Otis Houston Jr.’s catchy slogan paintings radiate a quintessentially New York sarcasm. Houston Jr., who started making art while incarcerated, is known for performing under the Triborough Bridge. His humor cuts through the surroundings: “You can’t raise the Roof of the House of Labor if the Floor is Caving in: The WORKER.” The line speaks to the tension at the heart of this spectacular event, however much the organizers have toned down the glitz this year. Whether you believe the fair parachutes onto a vibrant art district, or that the multibillion-dollar Hudson Yards property development profits from the veneer of culture, there is much work worth seeing within a few blocks of the fair (which is more than you could say for its old home on Randall’s Island). A few blocks north, Sean Kelly’s exhibition of Jose Dávila’s show “The Circularity of Desire” presents the Mexican artist’s research into the recurrence of circular forms in art history: his obsession is realized in silkscreens that recall the work of Hilma af Klimt and sculptures that bring to mind his nation’s history of modernist architecture.

A walk down the winding High Line—the elevated “urban park” repurposed from a disused railroad—sandwiches me between Chelsea’s luxury apartments and “The Musical Brain,” a group show of public sculptures commissioned by High Line Art. Entering on 30th Street, I am greeted by Raúl de Nieves’s three colorfully beaded sculptures of figures in the guise of musicians, each appearing rather like a hybrid between a human and another animal. The theme is continued, serendipitously, by a pigeon perching on one of the three vaguely biomorphic sculptures by Alma Allen visible in the “sculpture garden” on the roof of neighboring Kasmin Gallery; when it flies off, the bronze sculpture is transformed in my imagination from an eagle’s head back into a purely abstract form. Back on the High Line, the slow back-and-forth of Naama Tsabar’s vast metronome Equal Measure (2021), installed (with a view of the Empire State to the back) on a pedestal that recalls those from which statues have recently been toppled, seems in the current context to allude to the pace at which history changes. Even with all the novelty of this year’s fair, and the circumstances in which it takes place, that feels like the most enduring lesson.