A slim ochre publication by Algerian collective the Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie, or archive of women’s struggles in Algeria, has the light, open feeling of a notebook. It was produced to accompany their installation at Documenta 15 in 2022. The book was sold out by the time I got to Kassel in early September, and I would have to wait six months to find a copy, finally, in Algiers, one of six remaining from an informal shipment that had arrived the week before.

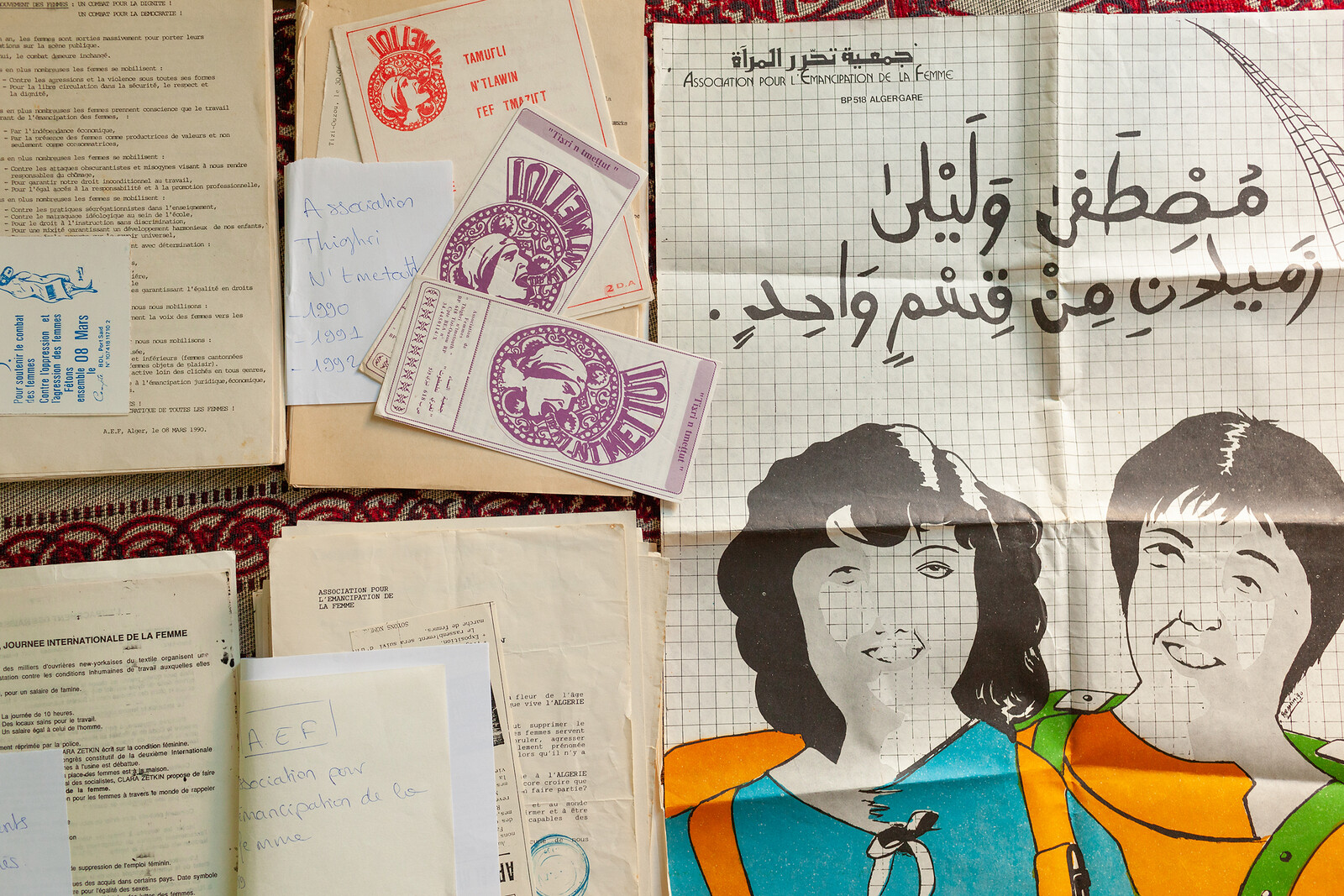

It is hard to find because the material Archives des luttes des femmes en Algérie reproduces—historical documents pertaining to women’s political organizations active in Algeria between 1988 and 1991—has rarely been seen, either inside or outside Algeria. The trilingual publication (in French, English, and Arabic) presents a selection of documents and photographs; an introduction and contextualizing essay about the International Women’s Day demonstrations on March 8, 1990, by one of the collective’s members, Awel Haouati; and a socio-historical treatment of the period in question by Feriel Lalami, an Algerian sociologist, political scientist, and feminist activist. Political tracts and photographs from what the authors describe as the “democratic breach” in Algerian politics are bracketed by designer Walid Bouchouchi’s signature bold typography and bright title pages, which give a sense of structure to a time of burgeoning public activism. As the collective’s statement on the back cover explains, this is a handbook of “tools of political struggle,” a struggle for women’s rights that was visible in Algerian public space for a brief space of time.

The collective comprises three members: Saadia Gacem, an activist and doctoral student in the anthropology of law who has spent years sitting in the municipal tribunal in Algiers listening to women contest the legal statutes that define many aspects of their lives; Haouati, a photographer and a doctoral student in social anthropology whose PhD is focused on the photographic representation of the Black Decade, a period of violent political unrest beginning in 1992 that swiftly followed the time of relative openness on which the collective’s work is focused; and Lydia Saidi, a photographer and image archivist whose work concerns historical images of women and the archival traces of slavery in Algeria. Their understanding of the ontological status of image shapes this volume, which does more than show proof, or make that proof public—a form that can be taken up by others. Together, they are activists of the image as a record of the agency, ambition, and organization of Algerian women.

One example of their understanding is the fact that the collective commissioned artists—Hichem Merouche, Sonia Merabet, and Sofiane Zouggar—to photograph and film their selection of materials. The first full-page image in the book, taken by Merouche, depicts a carbon copy document by the National Cooperation of Women’s Associations published during the campaign against electoral law in May 1990. The top copy of the typed communiqué is peeled back to reveal first the layer of carbon, then the transfer copy. Unlike most documents republished in the book, the text is almost illegible. The wide blank margins at the bottom of each legal-sized page and the dark carbon sheet between them take up most of the image. What the photograph renders is not the facts about a given electoral campaign but the material fragility of this history. The image seems to say: it happened this way, at typewriters on thin carbon paper, and the evidence is precious.

As Feriel Lalami lays out in her text, a breach opened in Algeria’s political landscape in 1989: a new constitution was passed that sanctioned multi-party politics and ended single-party rule by an elite group still identified as the National Liberation Front, the military organization that takes primary responsibility for the end of French rule in 1962. By early 1991, over thirty political parties were registered to take part in elections. It is in such a context, in which the rich diversity of Algerian political identification could be expressed for the first time in decades, that women’s rights organizations could finally apply for legal status and organize publicly.1

1988 to 1991 were not idle years. The book Archives de luttes des femmes en Algérie reproduces only a selection of material the group obtained through several years of research, found in the personal archives of roughly fifteen women, and this handful of pages still reveals an incredible momentum of political energy: clippings, leaflets, posters, satirical comics, legal reports on the status of women, education, and healthcare, receipts, and open calls to journals and conferences. Interspersed throughout are photographs by an anonymous photographer. A spread covering two pages, for example, is a black-and-white crowd shot of hundreds of people on the Boulevard Zighoud Youcef in central Algiers. Men and women are marching for International Women’s Day, March 8, 1990. On the left, the white-washed Haussmannian buildings of the city’s sea-facing colonial façade. To the right, the Martyrs’ Memorial is faintly perceptible in the distance.

Such mass-scale activism was abruptly closed off on January 11, 1992, when Algeria’s military staged a coup that triggered the Algerian Black Decade. The movement was forced back underground, where it would remain for decades partly in response to violence against women by the Islamist far-right. Two spreads positioned at either end of the book are stills taken from a video Saadia Gacem made with Sofiane Zouggar. The video, produced as part of the collective’s installation at Documenta, shows Gacem’s slim yet purposeful hands unpacking (the still at the front) and repacking (the still at the back) ephemera and other archival material. These are laid out on a brightly multi-colored kilim rug, its bands of diamond shapes and horizontal stripes in fluorescent pink and vivid green march insouciantly beneath the idiosyncratic order of the stacked documents. This is a living archive, the rug insists. We are alive to confirm it, Gacem’s silent hands reply.

For a more complete history of women’s political organizing in Algeria, see the collective’s website (in French): https://archivefemdz.hypotheses.org/a-propos.