In these necessary times of dismantling and revisionism, there is a case to be made for the explanatory wall text as one of the least rehabilitated pieces of museum orthodoxy. Can diagnostic writing reproduce the subtlety, particularity, and even obliquity of literature and still retain a radical function? It is a question I kept returning to reading the numerous, often undeveloped, expository texts that accompany curator Gabi Ngcobo’s exhibition, one of four shows inaugurating a new art museum at the University of Pretoria. “All in a Day’s Eye: The Politics of Innocence in the Javett Collection” stages a kind of truth commission through image and wall text, using works by some two dozen, mostly white South African artists amassed by the philanthropist Michael Javett to reframe sedentary positions of meaning, value, and importance, in particular by highlighting the “economies of access” and “political climate” that informed their production.

The show opens with a hoary genre painting by English-born Ivanonia Roworth, The Return from School, Genadendal (1954). This Barbizon-style work depicts two groups of children outside three thatched buildings, one topped with wispy smoke, in a community that was once a refuge for freed slaves; Genadendal, located at the foot of a mountain range near Cape Town, is also the site of the oldest mission station in South Africa, as well as the country’s first teachers’ training college. The date of the painting is significant: it follows the enactment of the Bantu Education Act of 1953, a key piece of apartheid legislation that shuttered mission schools through the creation of a centralized, white-controlled state body for black education. Protests ensued between 1954 and ’55, although this agitation, as the wall text makes clear, is absent from Roworth’s saccharine idyll of rural simplicity.

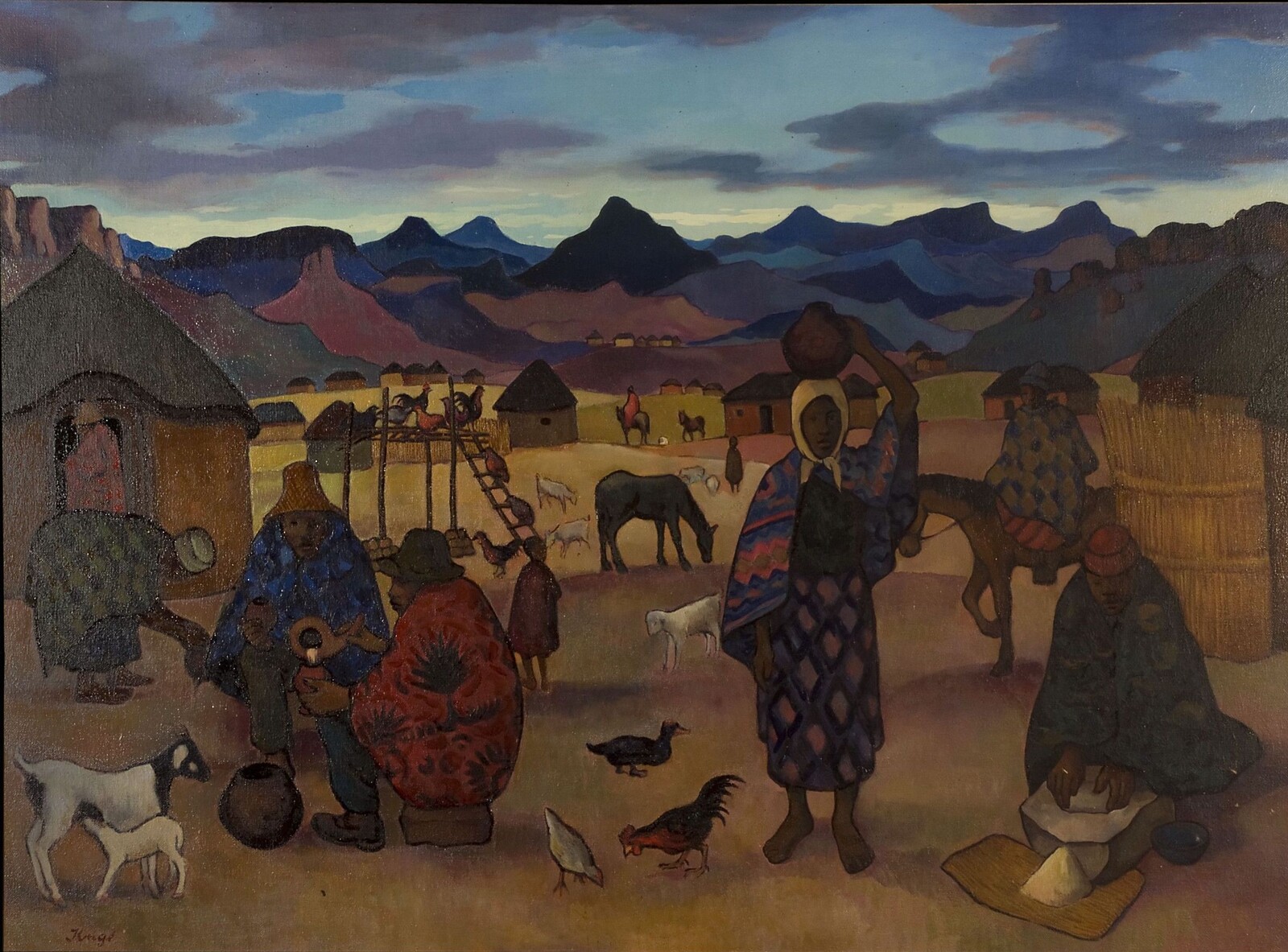

Schools and colleges in South Africa have long been sites of rebellion, notably during the Soweto uprising of 1976, and again between 2015 and ’16, when university students demanded free and decolonized education. In 2016, during a violent outburst at the University of Cape Town, 24 paintings were torched, including 4 works by Roworth’s father, Edward, a powerful apparatchik and Nazi sympathizer. Some of this backstory is rehearsed in the introductory wall panel, which proposes Roworth’s genre picture—its domesticated rural setting, vernacular architecture, and young, unthreatening subjects make it typical of earlier twentieth-century Cape-school paintings—as a vehicle to “re-understand the history of education in South Africa,” as well as a “frame” for this curatorial project, which includes art-historical research by artists Donna Kukama, Simnikiwe Buhlungu, and Tšhegofatso Mabaso.

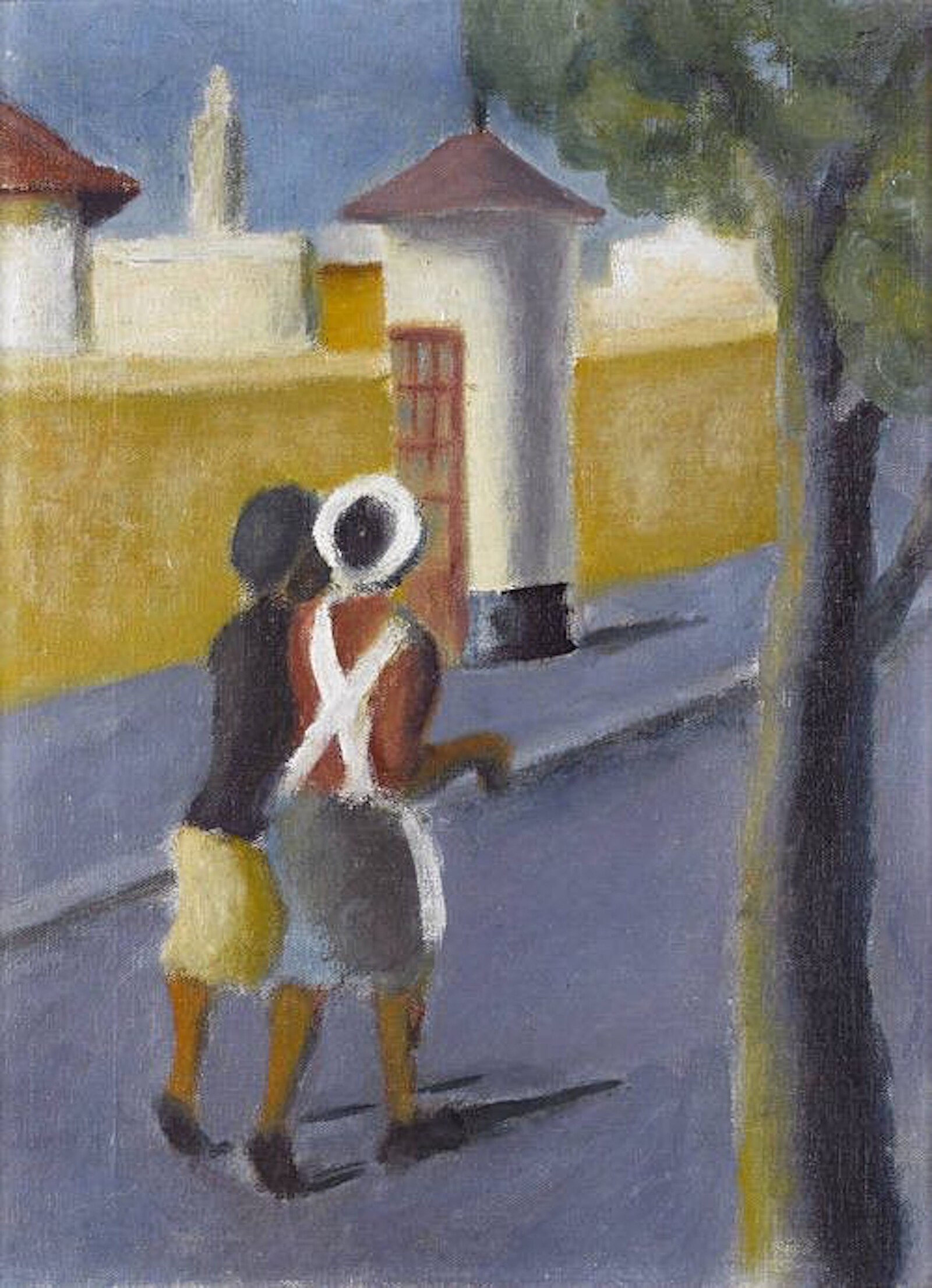

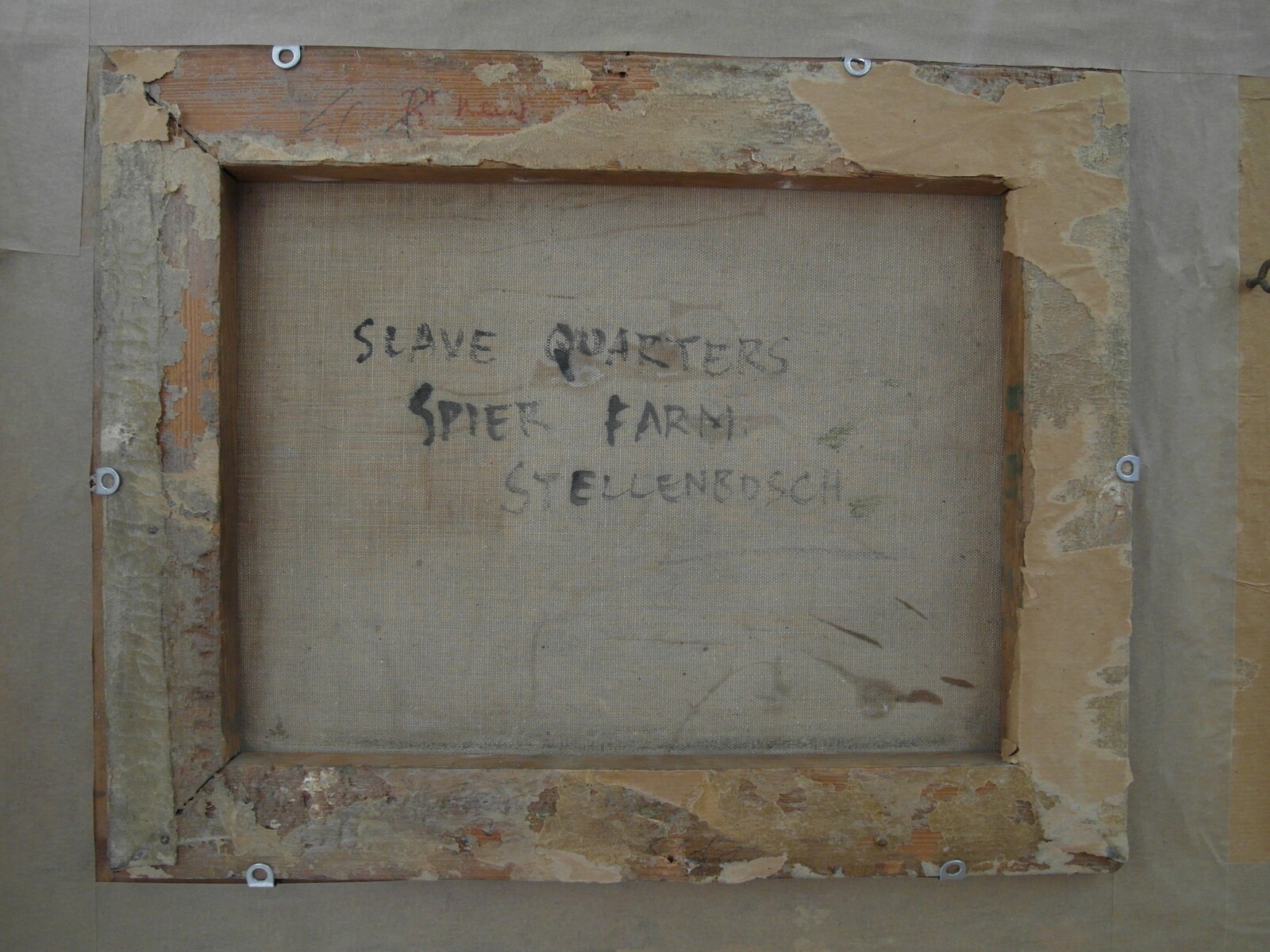

Installed opposite Roworth’s work at the entrance is another Cape genre painting: Freida Lock’s 1946 architectural study of a gabled Cape-Dutch building on a wine farm. The Jonkershuis, as it is known, was built in 1817 and used to house slaves. This fact was elided from the work’s received title, A Cape Dutch Homestead, even though the artist explicitly titled it, in large letters on the back, Slave Quarters, Spier Farm, Stellenbosch. Lock’s Post-Impressionist study is obliquely mounted so that this detail is made visible, which is not a new tactic in South Africa, but nonetheless a necessary one in a context where auction houses often parrot unreformed histories of white achievement. The accompanying wall text, written by Buhlungu, does not clarify the reason for the elision, only stating that the relabeling is “historically misleading” and initiated the “erasure of an unavoidable [sic] violent past”—the interpretive texts often rely on affect, rather than dispassionate scholarship, to argue a point.

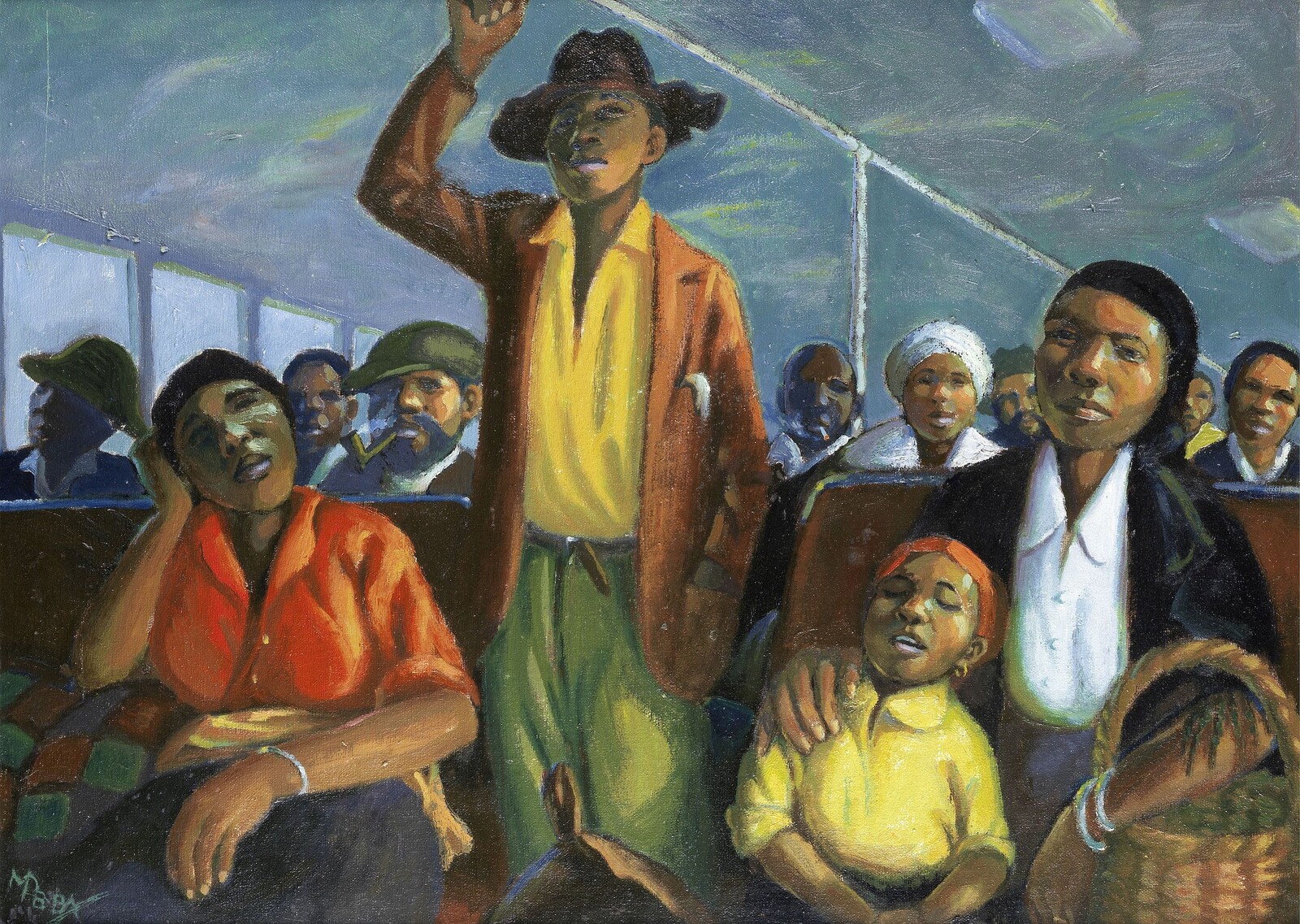

Titles, adds Buhlungu in the wall text, “provide interesting insights on the larger socio-political, historical, and cultural climate” of a work. This analysis informs many of the thematically organized selections, including a grouping of four portraits of black women wearing head wraps by Emily Fern, Gladys Mgudlandlu, and Gerard Sekoto. Both Fern and Mgudlandlu depict women of Xhosa heritage; Fern’s undated work, A Pondo Muse, makes some concession to this fact, but Mgudlandlu’s expressionist portrait from 1963 is merely titled African woman smoking a pipe. What does it mean to label an obviously black subject “African” in Africa? Buhlungu asks. And what of the complicity of black artists in this labeling?

Unfortunately, these and other provocations—like the pairing of Sekoto’s Waiting, a work from the 1940s depicting four black men lingering at a street corner, with a 2013 assemblage painting by Vusi Khumalo, Baipei Informal Settlement, to comment on the lived reality and unfulfilled promises of democracy—were overshadowed by the controversial inclusion of a work by Zwelethu Mthethwa. Best known internationally for his photographic portraits of shack dwellers, in 2017 Mthethwa was found guilty of killing Nokuphila Kumalo, a sex worker, four years prior. Flouting a tacit embargo on showing his work, Ngcobo selected a 1996 pastel drawing, The Wedding Party, and installed it directly adjacent Robert Hodgins’s The Hangman with the Harelip (1985–86), an unusually grim portrait of an executioner. South Africa’s Sex Workers Education & Advocacy Taskforce wrote an open letter and circulated a petition calling for the removal of the work; Ngcobo stood her ground.

Wall texts matter, as became clear during the heated deliberation over Ngcobo’s gesture. While the curator’s text clearly flags Mthethwa’s conviction for a “brutal murder,” it largely provides a formal analysis of a celebratory moment involving two intimate partners, the only such pairing featured in the show. Ekphrasis can be a form of judgment: Ngcobo’s analysis points to the passivity of the bride and the “performance of masculinity” in the gesture of the bridegroom, who is shaking hands with a male acquaintance. But it mentions nothing of Mthethwa’s 1986 marriage to artist Bongi Bengu, which lasted for two years, and allegations of impropriety that swirled around this unhappy union.

“Criticism is always a form of intervention,” wrote John Berger in 1969: “In most cases very little depends upon this intervention.”1 In Ngcobo’s case, the opposite holds true: the intervention proposed by this show is necessary, but remains unfulfilled. Without a supporting catalogue, the slapdash wall texts have to do a lot of work, for instance by justifying—unconvincingly—the grouping of three floral-themed works by Lock, Hugo Naudé, and Alexis Preller as a commentary on notions of “white innocence.” The preliminary nature of the wall texts nonetheless suggests a way to retrieve this critical intervention: “All in a Day’s Eye” is a valuable draft toward an important, and still-awaited, exhibition about the ideologies and inheritances of South Africa’s historical canon of painting.

John Berger, Art and Revolution: Ernst Neizvestny, Endurance, and the Role of the Artist (New York: Pantheon Books, 1969), 9.