“The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more. I prefer, simply, to state the existence of things in terms of time and/or place.” That once startling, now iconic statement by Douglas Huebler (1924–1997) was crucial to the foundation of Conceptual art. It was his contribution to Seth Siegelaub’s “January 5 – 31, 1969,” the exhibition without objects that launched Conceptualism. With those sentences, aimed at an art world dominated by Minimalist objects, Huebler announced that art was no longer an object: it was an idea, documented by means of language, photographs, or diagrams. It was also a matter of time and space. He was the eldest and most famous of the Conceptualists—including Robert Barry Joseph Kosuth, and Lawrence Weiner—who participated in that objectless exhibition, but in retrospect he was also the most elusive, puzzling, and least understood.

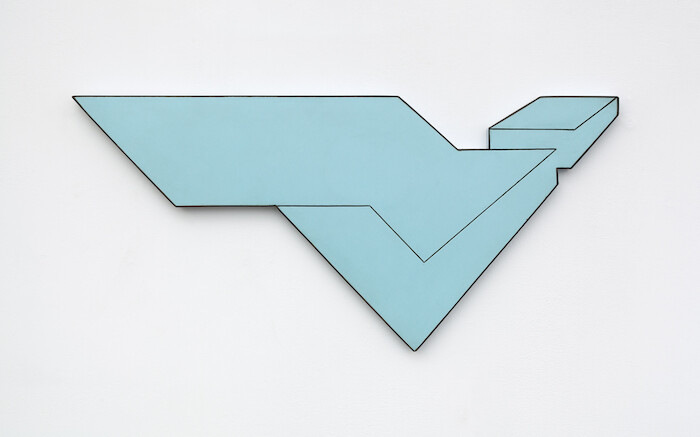

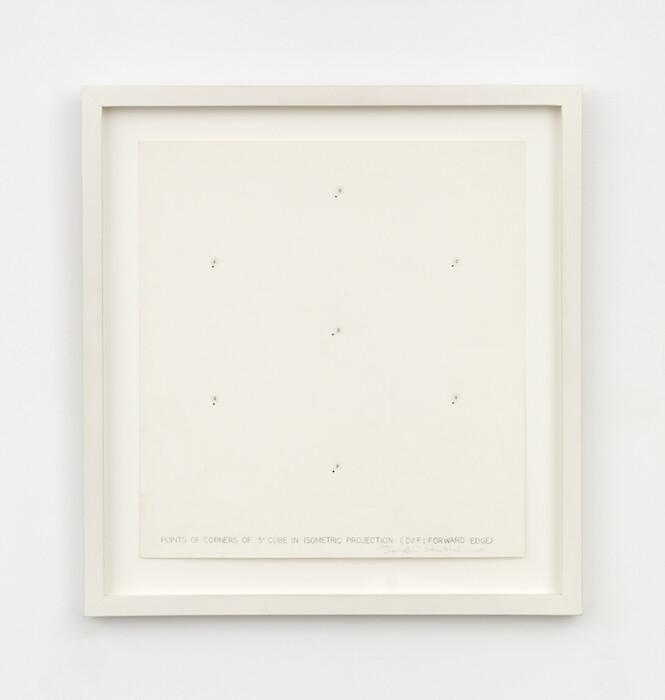

Almost half a century later, the current exhibition is not about what Huebler went on to do after that announcement—his “Variable” series, “Location” series, and “Duration” series (all begun in 1969)—and his quixotic attempt to document everyone on earth. Instead it offers the work he made shortly before that revelation: the quasi-Minimalist objects that were included in the landmark “Primary Structures” exhibition at the Jewish Museum in 1966, along with his earliest map documentations. Surfaced with Formica laminates in pale gray and yellow, or bleached gold and pale lavender, or simply black, their colors are not exactly the ones a true Minimalist would have chosen, but then, Formica veneer is not exactly a Minimalist material. Their stepped forms are sometimes frame-like, slipping between interior and exterior like a Möbius strip, twisting the idea of the object inside out while questioning location in space. At that time, Huebler said that designations of inside and outside “did not exactly apply because I was more interested in making forms that expressed extensiveness rather than interiority.”1 His early works on paper document random walks through city streets, mapping the messy actual world beyond the white cube, such as Hunt’s Point-Pelham Parkway Trip (1967) or White Church/Euclid Round Trip (1968). He also proposed a melting snow sculpture project and photographed actuality at the five points of a hexagram on a map. As he stated: “I wish to make an image that has no privileged position in space.”2

Huebler wasn’t satisfied to remain a Conceptualist; he had far too many ideas. His Variable Piece #70 (1971–1988) stated that it was “an attempt to photographically document the existence of everyone alive in order to produce the most authentic, inclusive representation of the human species that may be assembled in that manner.” This evolving project absorbed him the rest of his life. It mutated into a screenplay, Crocodile Tears (1979–1981), about a performance artist who is assassinated while performing over a swimming pool full of crocodiles. And within that ongoing and expanding project, it led him to re-introduce all manner of images, narratives, people, and objects—from comic strips to appropriations of Cézanne, Picasso, and Mondrian, and much more. Huebler, who served as a marine in World War II and studied under the GI Bill of Rights and in Paris, would most likely have absorbed the same sociopolitical ideas that influenced the Situationists, Guy Debord, and Joseph Beuys, whose concept of social sculpture was also formulated in 1971. Huebler was seeking a language for a democratized experiential interactive art in a context that barely existed at that time. He anticipated relational art. He taught at CalArts from 1976-1988 and influenced Mike Kelley, and may even have been an influence on Damien Hirst. Though I could find no documentary evidence, I’m sure I saw a live crocodile in an aquarium at the center of one of his exhibitions in SoHo. After helping to invent Conceptual art, he leapt beyond it—into narratives, measurements, indexical images, irrational systems, improbable objects, and the equalizing social aspects of the attempt to include everyone alive. Huebler appreciated the absurdities of his stance. The art world never quite forgave him.

“Primary Structures: Younger American and British Sculptors,” (exhibition catalogue) (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1966).

Ibid.