The transformation of the Polish Pavilion from a horror show into something closer to a miracle is one of the most remarkable stories of the 60th Venice Biennale. Last year, a jury predominantly aligned with the country’s ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party selected painter Ignacy Czwartos, whose nationalist-realist paintings support the right-wing narrative of Poland as a martyr of German and Soviet occupation absolved of complicity in Nazi-era crimes, to represent the country. After the Polish public voted out PiS last October, the decision was reversed. Curated by Marta Czyż, the pavilion now centers instead on an absorbing and poignant video installation by Open Group, an artistic collective from Ukraine.

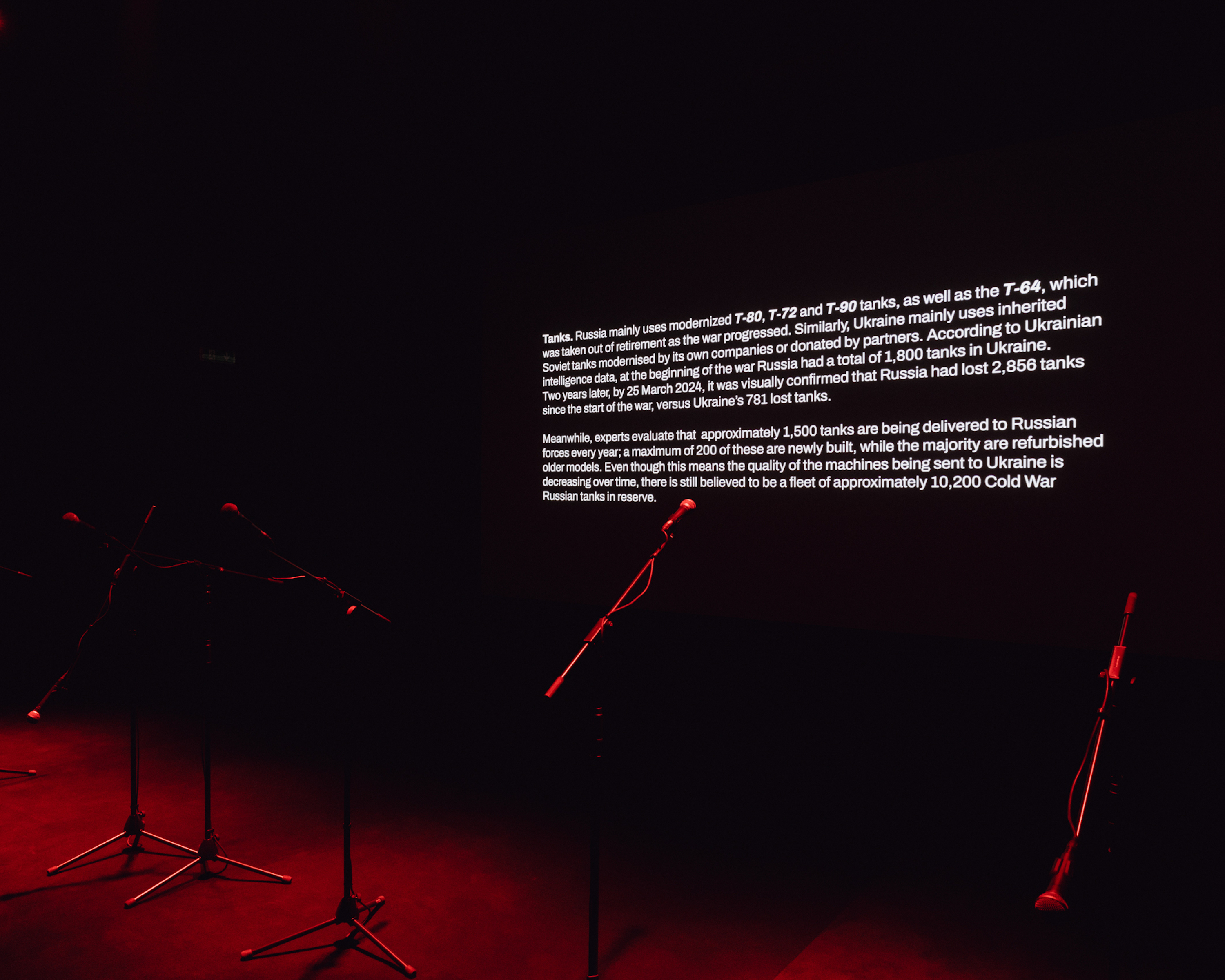

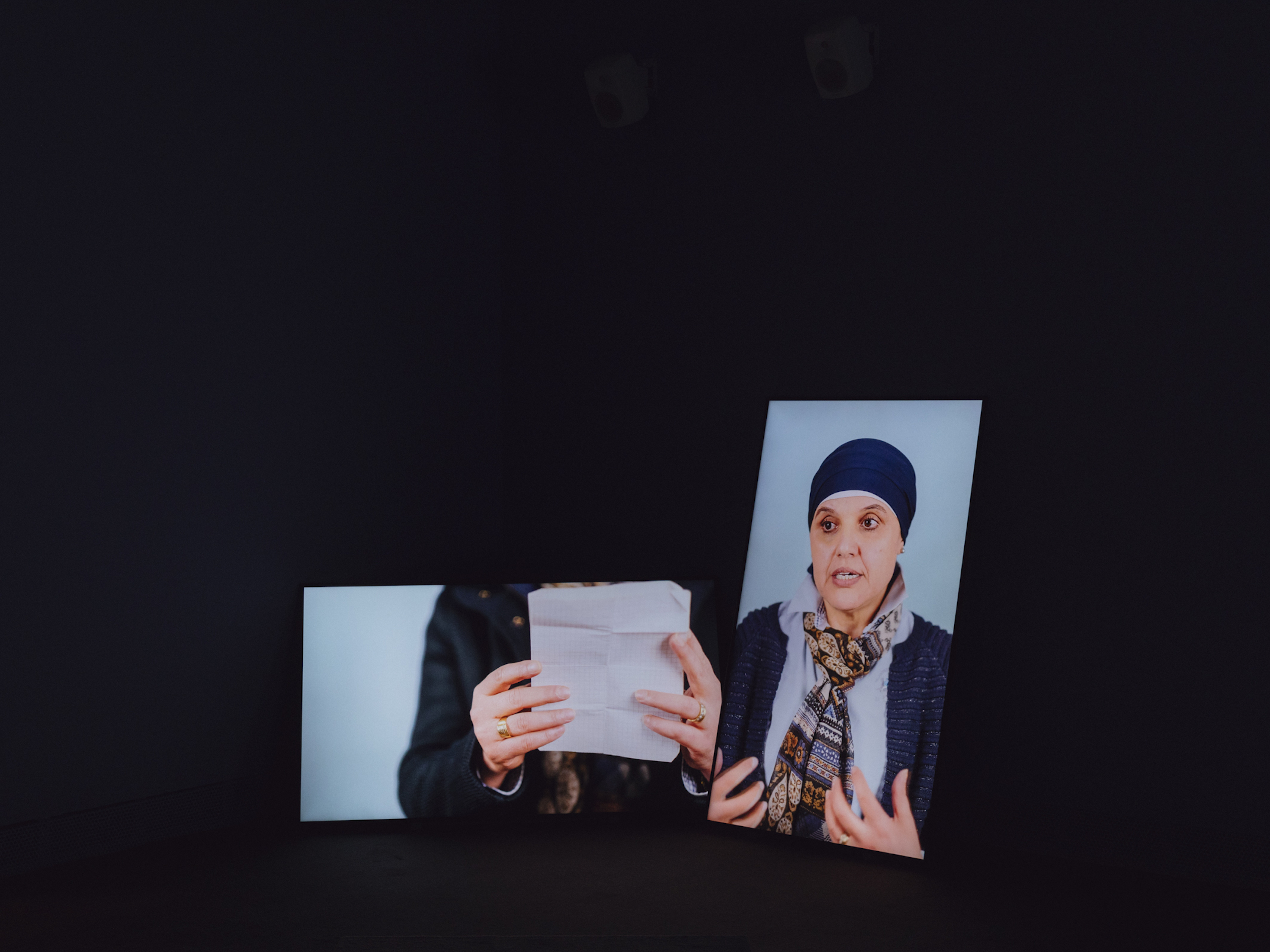

The group (consisting of Yuriy Biley, Pavlo Kovach, and Anton Varga) has installed a double video projection onto opposing walls. One video, shot in 2022, features eastern Ukrainian refugees who had fled to Lviv. Each briefly tells their story before imitating a war sound with their voice: the rattling of a machine gun (ratatatatatatatat), or the sound of artillery shelling (rrrhzzzzzzzzzzz-boom). A short text panel explains the military use of the respective weapon in the current war. Then they say the titular phrase “repeat after me” in Ukrainian while the sound being made is indicated with text, like lyrics in karaoke. The second video, shot in 2024 with Ukrainian refugees across Europe, expands the same principle. Each portrait gives a sense of the person (from teenager to elderly, and from all walks of life) and where they are staying (a residential complex in Poland, a garden in Ireland). Sometimes, the two projections and the sounds compete, as if intensifying Russian attacks—more drones, more shelling—have etched themselves into memory in traumatic, echoing layers.

There are microphones in the room but only a few visitors use them. A young woman makes the plop of artillery and turns around, embarrassed. Meanwhile, in another video scene, an elderly gentleman sits on a chair with the former Berlin airport Tegel—now a refugee camp—in the background. He imitates the buzzing and whistling sounds made by Russian hypersonic rockets, moving his head from left to right with closed eyes. When he’s done, his mouth twists into a slight smile, and his eyes are moist. No one leaves this room unmoved.

Blanket cultural boycotts against Russian-born artists—especially those in exile because of their opposition to the regime—seem self-defeating, as they weaken attempts to build diasporic alliances. Despite this, the five-member jury of the Austrian Pavilion chose Anna Jermolaewa who in 1989, aged 19, fled to Vienna from political persecution in Leningrad. In the patio of the pavilion, a row of discarded telephone booths, some of them functional, bears witness to that time (Untitled (Telephone Booths), 2024). They reference the Traiskirchen refugee camp in which Jermolaewa stayed. A wall text explains the phones were used to make more international calls than in anywhere else in Austria at the time. The video Research for Sleeping Positions (2006) documents the artist’s attempts to sleep on a bench at Vienna’s Westbahnhof station, as she did when she first arrived. This time, it is even more futile: armrests have since been installed to prevent people from lying down.

Three more works complete the picture. Ribs (2022/24) is a collection of Soviet-era flexi-disc recordings, in the form of grooves etched into discarded X-ray foils, allowing the illicit playing of banned Western recordings, from Duke Ellington’s Diga Diga Doo (1928) to the Beatles’ Back in the U.S.S.R. (1968). The Penultimate (2017) is an array of numerous flower arrangements and plants alluding to the symbol and/or color of a popular uprising—Portugal’s Carnation Revolution of 1974, Georgia’s Rose Revolution of 2003, Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution of 2010, and so on—as if awaiting completion by a floral contribution from Russia. During previous crises in the Kremlin, such as after the deaths of general secretaries, Soviet television would be interrupted by a prerecorded Bolshoi production of Swan Lake (1877), inadvertently associating Tchaikovsky’s ballet with the possibility of political change. Jermolaewa brought this idea into the present by commissioning Ukrainian choreographer and ballet dancer Oksana Serheieva to rehearse the piece both on video and in scheduled on-site appearances, in a present-day conjuring of potential regime change (Rehearsal for Swan Lake, 2024). With a light but precise touch, Jermolaewa’s pavilion elicits a strangely uplifting vision of oppositional self-assertion in the face of seemingly insurmountable power structures.

Nothing light about the German Pavilion. The entrance is blocked by a pile of earth, as if a giant mole had burrowed under the columns of the portico. Curator Çağla Ilk has brought together theater director Ersan Mondtag and artist Yael Bartana. Entering through the back entrance, the first thing you encounter is Bartana’s suspended Light to the Nations – Generation Ship (2024), the model of a spaceship shaped like the Kabbalistic Sefirot. In the central space of the three-part, mausoleum-like pavilion is a second mausoleum: a three-story building clad in rough, dark-brown plaster rising out of the ground like a submarine tower.

Monument eines unbekannten Menschen [Monument to an unknown person] (2024) is dedicated to Mondtag’s grandfather Hasan Aygün, who came to Germany as a guest worker in 1968. Aygün’s certificate of honor for twenty-five years of service as an employee of the Berlin branch of Eternit AG hangs on the wall of the entrance room: he died as a result of working with the asbestos used in the company’s patented fiber cement panels. The Venetian earth at the entrance is mixed with Anatolian earth—grave soil. Inside the monument, glass cabinets display Aygün’s personal belongings while white dust has settled like mildew, including on a monitor and speakers that play composer Beni Brachtel’s requiem, featuring traditional Turkish instruments.

A live choir later sings to the music, mingling with the visitors. Their singing mingles, in turn, with a deep, ominous bass coming from the apse of the pavilion, where Bartana’s huge vertical LED screen is fitted into the semicircle wall (Farewell, 2024). Some of these monumental scenes—a posing torch bearer, a discus thrower—directly allude to (and parody) Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia of 1938, while others—young men and fairy-like creatures in semi-transparent robes dancing in circles in forest clearings—reference Hungarian choreographer Rudolf von Laban. Laban was due to choreograph the opening ceremony of the 1936 Olympics, but after attending a rehearsal, Joseph Goebbels banned it. Bartana deliberately goes into overdrive: as the dancers await the spaceship, they leap in slow motion, wearing rubber animal masks, and the pathos tips over into parody. With Mondtag, into melancholy.

The curated constellation of a German artist with Turkish roots and a Jewish-Israeli artist living in Berlin is more than a tokenistic representational act. The children and grandchildren of the guest workers in Germany still have to fight for their history and this exclusion is alarmingly linked to antisemitism in conspiracy narratives, such as the “great replacement” or right-wing talk of “imported antisemitism” that blames a rise in antisemitism solely on immigrants. Bartana meanwhile offers to the Jewish diaspora a science-fictional salvation, thereby pointing to the entrapment of the present, in which any salvation—a road towards a peaceful solution in Israel/Palestine—is hindered by a deadly embrace of militantly extremist positions, including by Netanyahu’s government. In the third room, the computer animation projected onto the domed roof (Life in the Generation Ship, 2024) depicts green gardens and clean spaces, as if riffing on Neill Blomkamp’s film Elysium (2013), in which a utopic space station orbits a cataclysmic Earth.

The small island of La Certosa—a former friary and military installation—is worth the trip: four artist-musicians (Michael Akstaller, Nicole L’Huillier, Robert Lippok, and Jan St. Werner) have installed subtle sound works that alter the experience of an unusually quiet and natural piece of Venice into a surreal scenario out of a dystopian B-movie. St. Werner’s custom-made loudspeakers, rotating slowly in the ruins of a monastery, and on a wooden post marking the waterway, emit an otherworldly robot cricket sound, like a retro-futurist artefact warning of imminent but entrancing danger (Volumes Inverted, 2024). Where the pavilion is packed, this is as wide open as can be. Hopefully this wide-openness—less determined, less fraught with meaning, but rather pointing to the state of things—anticipates better futures, not worse ones.

This is the third in a series of responses to the 60th Venice Biennale to be published by e-flux Criticism. More perspectives—on the national pavilions, collateral shows, and international exhibition—will be published before the Biennale's end.