Masked commuters emerging blinking from quarantine and into Yokohama’s bayside district might think that the Museum of Art has disappeared. In place of its 180-metre-wide modernist façade is a dark, striated screen that—in fitting with the subtitle of the seventh edition of the Yokohama Triennale—resembles an analogue television screen patterned with the white noise caused by cosmic radiation from the “afterglow” of the Big Bang. Closer inspection reveals the source of this illusion: mesh drapes, patterned with vertical black-and-white stripes, have been suspended across the front of the building. This optical intervention by Ivana Franke, titled Resonance of the Unforeseen (2020), anticipates the haunting ways in which themes such as “luminous care” and “toxic glow” radiate through the exhibition.

Curated by New Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective, this edition of the triennale brings together 67 artists—many of them exhibiting in Japan for the first time—whose work engages with diverse belief systems, histories, and forms of sensory experience. The first non-Japanese artistic directors of the triennale state in an introductory text that their curatorial methodology is to “start with the sources” in order to “provoke us to think, to ignite, to learn, and unlearn.” These are collected in a “sourcebook” published online, “a compilation of words, text, experiences, and visions” connected by issues of care, toxicity, luminosity, and migration.1 Ranging from an anthropological study of a self-taught philosopher from Yokohama’s slum district, to a Bengali woman’s first-hand account of travelling to Japan, originally published in 1915, and a summary of an Indian astrological encyclopaedia from the sixteenth century, the sourcebook is a multivocal articulation of peripheral narratives across diverse geo-historical contexts.

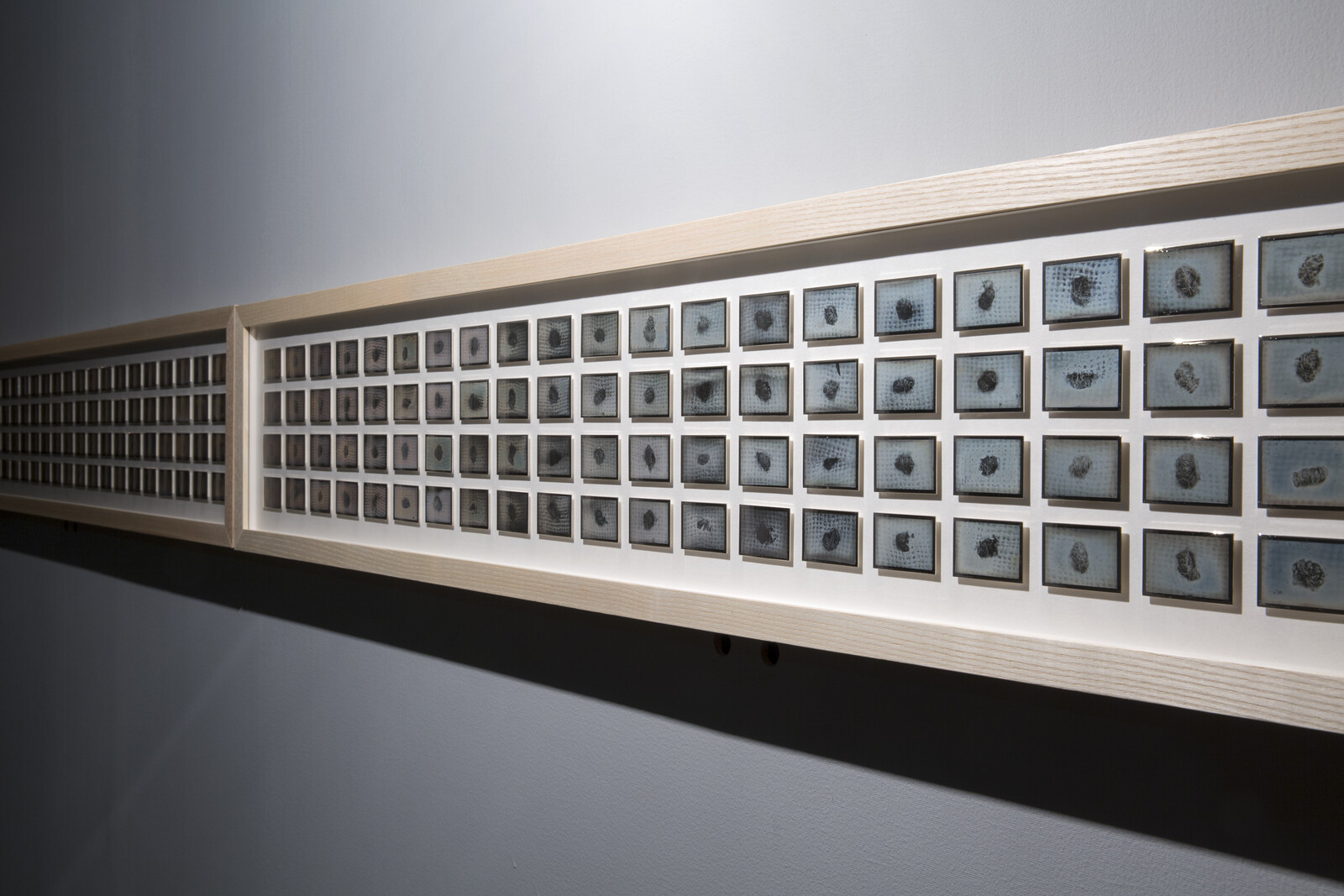

In Yokohama, the curators’ interest in “our connected and contiguous landscapes” manifests in a series of exhibitions, performances, and workshops across three physical venues and an online platform containing video clips of performances and sculptures included in the exhibition. On passing through Franke’s artwork and entering the Yokohama Museum of Art, a series of newly commissioned works testify to the ethos of collaboration and diversity evident in the sourcebook. Takashi Arai’s work is one standout example. Comprising a video and photo installation, his Multiple Monuments for 1000 Women No1-10 (2020) explores the folk belief and practice of senninbari: waistbelts embroidered by women for Japanese soldiers, notably during World War II, that were intended as good luck charms to protect their wearers. Each photograph in the artist’s grid of 1,000 daguerreotypes depicts a single stitch in a senninbari, or “one-thousand-stitch,” and was manually developed on a silver plate: the painstaking process of polishing each daguerreotype plate’s surface for a long, durational exposure both reflects and memorializes the labor of the women who made the stitches.

Two further works displayed nearby continue the theme of intergenerational memory and inheritance. Asako Iwama’s A mound of shells (2020), a video projected in a darkened room flanked on both sides by curtains of reflective mirror foil, is based on diaries by the artist’s late father, an ethnographer who stayed in a crop-farming village in a Tamil Eelam region of Sri Lanka. Speaking over footage where she examines various archive materials—diaries, maps, agricultural research documents, black-and-white photographs of the landscape—the artist reflects in digressive, essayistic mode on agricultural water channels, mounting concern about nuclear power, and her parents’ house in Kamaishi, which was destroyed by the 2011 tsunami that precipitated the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Yuki Iiyama’s Moomin Family goes on a Picnic to see Kannon (2014/2020) is a funny, absurdist skit in which the artist and members of her family perform a narrative set in the “hallucinated” mind of her sister. Though they differ in tone and content, both works succeed in exploring unmapped emotional geographies at the fringes of dominant belief systems.

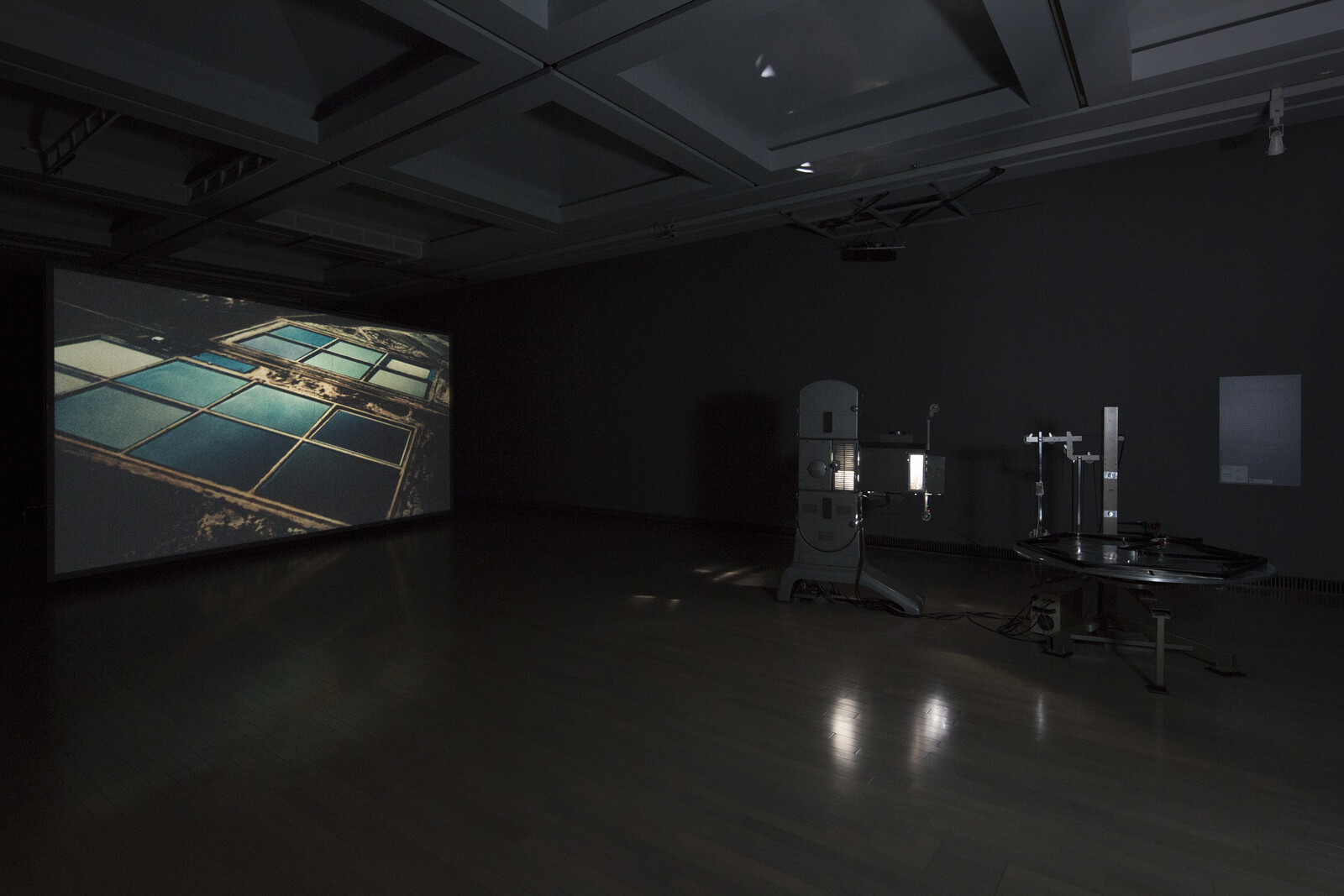

The radioactive waste sites depicted in Rosa Barba’s looping 35mm film projection Bending to Earth (2015) offer a conceptual touchpoint, evoking “toxic glow” and suggesting how seeming opposites, such as beauty and suffering, are mutually constitutive. Park Chan-kyong takes this idea further in his 55-minute film Belated Bosal (2019). Shot in glowing, black-and-white photonegative, the film follows two women as, separately, they cross mountainous terrain and perform a burial ritual. Interspersed with this footage, which references Buddhist depictions of nirvana and a story of the Buddha’s disciple running late for his cremation, are references to “Smiling Buddha,” the code-name for the site of India’s first successful nuclear bomb test in 1974. The sinister, irradiated landscapes of both works are haunting reminders that, as the curators put it in the sourcebook in reference to the glowing light given off by the meltdown of nuclear reactors, “the toxicity of our time has to be encountered with a cultivation of this spectral glow.”

Across town at PLOT 48, a series of works with an altogether lighter, more playful mood explore gender-specific sources of bodily abjection, interspecies queerness, and science-fictional cosmologies, turning the former children’s entertainment complex into a playground for adult unlearning. In the installation Volcana Brainstorm (2019) by the Tokyo-based artist Elena Knox, books, small sculptures of sea shells, caricatured sketches of prawns, and computer graphics depicting human bodily functions are arranged on display cases and hanging mobiles in the manner of a museum gift shop. By creating “pornography for prawns,” the artist points towards possible ecological futures predicated on empathy between humans and animals. Echoing this theme, Zheng Bo’s video installation Pteridophilia 1-4 (2016–19), viewed from the comfort of transparent cushions of inflatable plastic, stages a series of erotic encounters between lush green plants and naked young men. A framed replica of Hokusai’s 1814 shunga The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife, which depicts a woman being sexually embraced by two octopuses, hangs nearby, setting these explorations of interspecies desire in a broader art-historical context.

If last year’s Aichi Triennale resulted in a divisive ideological clash over the inclusion of Sculpture of a Girl of Peace—Kim Seo-kyung and Kim Eun-sung’s 2011 work depicting an ianfu, euphemistically known as a “comfort woman,” which embroiled the organizers in accusations of censorship after they closed part of the exhibition—Raqs’ all-embracing approach and commitment to dialogue over didacticism suggests a post-structuralist critique on the grounds of knowledge, justice, and operations of power. Being the first large-scale exhibition to open during the pandemic, however, brings its own challenges. Social distancing and face masks make—ironically for an exhibition that argues against artificial separation and for the dissolution of borders—for a necessarily, but disappointingly, sanitized experience. The greatest loss is the physical absence of the artistic directors and most participating artists. The forms of learning and knowledge production advanced by this wide-ranging exhibition are based on precisely the forms of public discussion and collaboration that, at least for the foreseeable, are no longer possible. In the absence of in-person conversation, it is left for exhibition elements such as the wall texts—a series of fragmented phrases and words that runs like a voiceover through the exhibition—to advance this triennale’s evocative and haunting effects. By foregrounding cross-referentiality and indeterminacy, the exhibition is a timely reminder of how meaning is constructed: across borders of genre, medium, nationality, and species, and in the afterglow of our changing, contingent present.

Raqs Media Collective, Sourcebook (Yokohama Triennale, 2020) https://www.yokohamatriennale.jp/english/2020/concept/sources/