Which Citational Practices?

Citational practices have come under review in several recent settings. In 2020, Annabel L. Kim edited an issue of Diacritics called “The Politics of Citation.”1 Curator Legacy Russel delivered her lecture “On Footnotes” in 2021.2 In Parse Journal’s 2023 issue “Citation,” editors Kathryn Klasto and Marie-Louise Richards facilitated a discussion that went beyond the binary of citing and plagiarizing: they deployed various artistic and cultural practices to examine the motivations behind and implications of citational decisions. Beyond the academicism of citational mobility, recent efforts have been made to think through citation within the context of exhibitions, such as in scholar Lucy Steeds’s writing on “restaging historical exhibitions.”3

Contemporary citational projects have also taken the form of audio broadcasts and exhibition-making centered on spacious quotation of impactful written work. For example, Chimurenga, an arts organization and publisher in Cape Town, aired a radio program last July celebrating what would have been the eighty-fifth birthday of legendary South African and Botswanan writer Bessie Head.4 Similarly, curators Nontobeko Ntombela and Portia Malatjie used Head’s 1968 novel When Rain Clouds Gather as a title and framework for their yearlong exhibition at the Norval Foundation, Cape Town, which traced a history of Black women in South African art from 1940 to 2000.5 In addition to novels and short stories, Head also wrote art criticism; in 1963, she reviewed an exhibition of modern painter Gladys Mgudlandlu for the New African periodical.6 According to reviews like Head’s, as well as eye-witness accounts, the exhibition positioned Mgudlandlu at the very heart of the history of Black women in South African art.

Feminist Readings in Motion?

In 2020, we wrote a panel proposal for “Feminist Readings in Motion?,” a conference that was supposed to be held later that year at the University of South Africa in Pretoria. The conveners, including scholars Leandra Koenig-Visagie and Motlatsi Khosi, framed this gathering with ideas that have been proliferating—particularly in Africa—on the “diversity” and “richness” of feminisms. The conference, eventually held online in April 2021, activated conversations that have preoccupied us on the role of African authors, intellectuals, novelists, and curators within curating and twentieth and twenty-first century art history.

One initial aim of our panel was to use the metaphor of migration—that is, to interrogate how texts and citations move from one context to another. As mentioned above, we witnessed how a range of South African artists and curators whose work had traveled internationally cited Bessie Head. We asked: Why, then, is Head not better known outside her country of birth? We also intended to ask the following question: Since Head kept correspondence with Langston Hughes in the United States, what does it mean that her work is little known in that country today?

The panel we held, titled “US-SA Feminist Solidarities: Citational Practices in the Visual Arts,” encompassed these and further discussions between curator and art historian Portia Malatjie; scholar and curator Nontobeko Ntombela (as panel chair and moderator); artist and curator Nkule Mabaso; and editor, writer, and scholar Serubiri Moses. Collectively and as individuals, the speakers brought a lot to bear in debating the nationalization of discourse, exhibitions as discursive forms, the transnational in the field of artistic practices, global Black conceptualism, solidarity, the spiritual dimensions of Black women’s activism, the ethics of “being in the world” and “being with others,” and biography. This report reflects critically on that panel discussion.

For reference, the full abstract for the “Citational Practices” panel described our intent to

extend the metaphor of migration in the visual arts through its explicit focus on the transnational framework of feminist solidarities across the continents of North America and Africa, and highlight contemporary negotiations of difference, politics, and community in a broad range of gender-identity struggles in South Africa and the United States. The panel seeks to problematize the reading of black feminist literature in the context of the visual arts. The metaphor of migration is explored by focusing on United States–South Africa linkages in the area of black and African feminist discourse, through an examination of citational processes in contemporary South African scholarship. By addressing US black feminist literature and African writing on feminism, the panel further elaborates on feminist solidarities through a critical analysis of citational practices. Such an analysis may consider such propositions as how to resolve the citational practices that shaped US black feminism in dialogue with African women authors, for example. How has Bessie Head been cited by Toni Morrison, or how has Micere Mugo been cited by Angela Davis? Inversely, how have black American women authors been cited in the domain of South African visual arts? Specifically focusing on pertinent issues within the visual arts concerning race and gender across the Atlantic, the panel seeks to address the questions of lack that pervade the discourse of art history in South Africa. In this regard, there will be a specific focus on the lack of solidarity within art history and contemporary criticism concerning black women as artists or scholars. Thus, the panel seeks to reflect on the idea of refusal as a critical gesture, and the notion of agency for black women in South African art history and contemporary criticism.7

Transgenerational Communion with Oneself

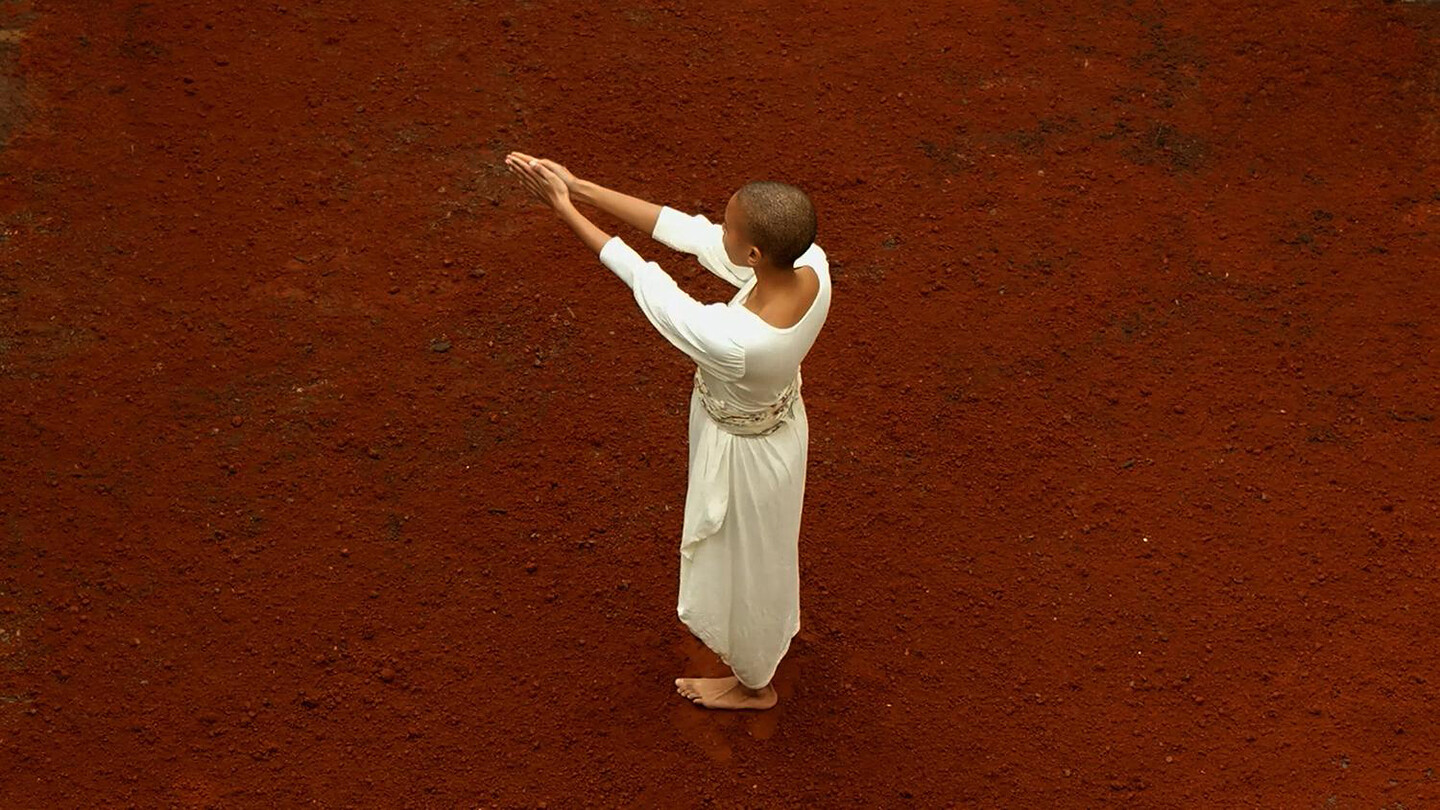

Portia Malatjie’s conference presentation, “Queering Ancestry: Transgenerational Communion with Oneself,” borrowed its title from South African trans and queer performance artist Lukhanyiso Skosana’s idea of becoming her own ancestor. Following an artwork that Skosana made in 2020 called The Exorcism of Mary Magdalene: A Sexual Resurrection, Malatjie theorized that Skosana engaged in “transgenerational communion with herself” and that she “(queered) ancestral citations.” Malatjie’s paper, which also discussed the artwork of South African artists Bronwyn Katz and Sethembile Msezane, framed citation through biography as a way of contemplating “being in the world and beyond it.”8 However, this notion of “becoming one’s own ancestor” was not Malatjie’s entry point. Rather, Malatjie began her presentation by meditating on her grandmother’s funeral and showing an image of red soil, which evoked the soil thrown into her grandmother’s grave. This starting point ultimately brought Malatjie’s family story into contact with politics and activism. Like Skosana, who staged a symbolic death and return in The Exorcism, Malatjie opened her discussion with her grandmother’s death, before detailing the political activism and spiritual work of Black women, including spiritual healers Nongqawuse (1841–38) of South Africa, Cécile Fatiman (1771–1883) of Haiti, and Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana (1840–98) of Zimbabwe.

Evoking these figures from history also gestures toward eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Black political movements such as the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) and, in present-day South Africa, the first Chimurenga (1896–1900) and the Xhosa cattle-killing movement (1856–67) (though the famine that followed the latter movement furthered rather than hindered colonization). Such attempts to think more historically alongside contemporary art unfold not through archives but through spiritual practices that challenge the epistemicide of colonization. These actions widen the scope of history by situating citational practice in spiritual and physical dimensions.

In a recent lecture, Ngugi wa Thiong’o stated that “our body is the primary source of knowledge” and that “the next primary source of knowledge is our body’s interaction with the environment.”9 This perspective helps to expand Malatjie’s reading of Skosana’s work. If Skosana’s metaphoric death, by which she becomes her own ancestor, leads to “renewal spiritually and physically,” then her return to the earth is one of the ways that her ancestry is realized. Malatjie implied this early on in her paper when she said that the soil in South Africa wasn’t always red. It was reddened, some have claimed, by the blood of Black people shed through acts of colonial violence and genocide.

The 2022 Dakar Biennale of Contemporary Art featured a video by Bronwyn Katz, one of the artists discussed in Malatjie’s conference presentation. Biennale curator Greer Valley’s exhibition thesis rested on “considerations of land as sustenance; as a register of embedded colonial violence and trauma; and as a sonic archive or repository.” In displaying Katz’s video, entitled Wees Gegroet, alongside other works on land and trauma, Valley’s exhibition gestured toward a site of future possibilities. In the catalog essay, Valley borrowed from artist Zayaan Khan in saying that the exhibition offered a “generative space” to “reclaim culture” and “revive tradition” through acts of listening and survival.10 Through such citations, Valley countered “imposed land histories.” By “thinking with and through the past,” she wrote, “we move towards future possibilities.”11 For Malatjie, such possibilities are “healing” insofar as they realize the potential of Black ontologies and Indigenous knowledge. Ultimately, Malatjie views Black women’s spiritualities as “forms of activism, resistance, and radical citation.”12

Imani Jacqueline Brown, Will the river remember the land we lost?, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

The variety of issues that Malatjie touched on in her presentation also recalled the work of Imani Jacqueline Brown, who builds on the notion of Black ecology through the lens of Afro-diaspora spiritual practices. Brown asks: “How might a Black defense of the ‘rights of nature’ manifest when we must still demand the basic recognition of our humanity? What might our multigenerational experiences of dispossession and disinvestment, of uprooting and regrowth—of diaspora—teach the world about ecological justice as a practice of solidarity?”13 This question reminds us further about the challenge of epistemicide. Suppose, as Ngugi wa Thiong’o said, that the sustenance of embodied knowledge is wholly dependent on the environment. In this case the active destruction, pollution, and theft of land is equally an attack on the production and preservation of ancient and embodied knowledge. Black ontologies, then, are dependent on ecological justice.

Being with Others

In her response to Malatjie’s presentation, art historian Nontobeko Ntombela invoked the isiZulu terms “ukukhapha” (to accompany) and “ukukhashwa” (guidance) to signal a turn towards an ethics of giving advice and guidance, which she considers a way of “being with others.” In this sense, she proposed an ontological framework for recognizing healing and spirituality as ethical practices. If Malatjie contemplates biography as a way of “being in the world” / as Black ontology, then Ntombela positions the agency of citation within ethics, as a way of “being with others.”

Here we recall Annabel L. Kim’s reference to citation as a metric and currency for academic labor and success.14 Citational practice in this latter sense, argues Kim in Diacritics, is a capitalistic enterprise in which only a few can stand out in an academic market: citation itself becomes a currency that in turn generates more currency. As a result, scholars must publish—and be sufficiently cited in other publications—to receive academic promotions and tenure positions. Kim defines the politics of citation in such a competitive environment, referring to a “certain model of reference” that must be adhered to “in order to be allowed to pass through the gates of intellectual legitimacy.”15

Ntombela counters such citational models through her turn to ethics, which, as she has elaborated elsewhere, reflects the linguistic turn to oppose epistemic violence. In her essay “Untranslatable Histories” she theorizes the untranslatable as an antidote to the problem of a “single story.” She writes: “It is important to leave certain things untranslated because some stories are embedded in the culture of the language, that is cultural codes and references that are sometimes not interpretable, and it is important to leave those nuances untampered with.”16 Here, Ntombela’s notion of the untranslatable meets with Malatjie’s argument for Indigenous knowledge and Black women’s spiritualities as forces to counter ongoing forms of oppression.

How Do We Mark History in the Present?

Serubiri Moses’s presentation, titled “In the Footnotes: The Discourse in the Margin and Center,” followed Black American novelist Toni Morrison’s idea of naming other positions to transform the reading and writing of Black subjects.17 Serubiri’s presentation continued the debate on citation by momentarily disengaging from locations or sites of ongoing political struggle and Indigenous knowledge to positioned citation as an act of transnational solidarity. This act, which treats citational references and footnotes as a space of solidarity, might appear inconsistent with the academic market’s emphasis on citational value and publishing as a form of careerism. By positioning citation as solidarity, Serubiri’s paper was akin to Ntombela’s remarks on the ethics of “being with others.” By way of example, he offered an analysis of Black American art historian Kellie Jones’s essay “Postapartheid Playground” (2004), which is a focused study on South African artist Tracey Rose.18 To grapple with Jones’s citational practice fully, Serubiri located the article within a geographically transnational context involving the United States, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, as distinct geographies with a shared discourse on Black conceptual art practices. In this sense, he considered how exhibitions themselves become forms of citation and knowledge production.

Black conceptualism was forged in transnational exhibition contexts such as the Second Johannesburg Biennale (1997) in South Africa, which included a range of conceptual artists such as Rose, Candice Breitz, Lorna Simpson, and Fatima Tuggar. Jones included the latter two artists in her own exhibition in the biennial, called “Life’s Little Necessities: Installations by Women in the 1990s.” In positioning the 1997 biennial as a producer of Black conceptual art history spanning the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Africa, Serubiri showed how writing history in exhibition form can encompass “solidarity”—if we understand this as both a political and intellectual practice.

Serubiri’s paper also detailed how Kellie Jones’s research in South Africa during the Second Johannesburg Biennale shaped her influential 2004 essay on Tracey Rose. Jones would have seen Rose’s work in “Graft,” an exhibition curated by Colin Richards at the South African National Gallery in Cape Town during the 1997 biennial. Rose’s work in that show, a performance and video piece called Span II, features a naked Black woman inside a vitrine sitting on a lopsided television, which displays a video work. “Rather than being gainfully unemployed as a passive object of desire” in this setting, notes Jones in her 2004 essay, “Rose methodically knotted lengths of her discarded hair.”19

Coco Fusco, Rights of Passage, performance, Second Johannesburg Biennale, 1997. Courtesy of the artist.

In her citation of Span and “Graft,” Jones also theorizes Black conceptual practice in a transnational manner. “While having specific significance in the South African context,” she writes, “Rose’s performances also connect with others of similar function and intent that have taken place in other parts of the globe.”20 She goes on to view Rose’s work in line with that of Cuban American artist Coco Fusco and Mexican American artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña, as well as Black American artists Adrian Piper and David Hammons. Instead of focusing on located, nationalized discourses of ongoing political struggle or on Indigenous knowledge in South Africa, Serubiri, citing Jones, examined Rose’s art as part of a transnational feminist project. This lasting project includes artists like Fusco, who also showed work at the 1997 biennial. Of course, Fusco and other artists’ work continued to influence the local Johannesburg scene long after the biennial closed.

As curator and artist Gabi Ngcobo has noted, the Johannesburg Biennale, which had only two editions, in 1995 and 1997, “remains a specter in the South African art scene.”21 Noting that the biennial was part of an internationalizing effort after the decades-long cultural boycott of South Africa, Ngcobo argues that “its phantom thus also exists outside of South Africa.”22 Okwui Enwezor, who curated the Second Johannesburg Biennale, popularized a model of group-based curatorial practice that inherently operated along cross-citational lines. Given the large scale of the biennial form, such citational processes could take on vast and daunting trans-geographic art histories. Some of the linked histories represented in the biennial were those of Cuba, Hong Kong, the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Africa, among others.

In his presentation, Serubiri delineated a constellation of interrelated exhibitions showing Black and African conceptual artists. In addition to the First and Second Johannesburg Biennales, this constellation includes the exhibition “Authentic/Ex-centric: Africa In and Out of Africa” at the 2001 Venice Biennale. These three exhibitions initiated a collective history of what Enwezor described as global conceptualism (following the 1999 Queens Museum exhibition of the same name, curated by Jane Ferver, Rachel Weiss, and Luis Camnitzer).

By asking “how we mark history in the present,” Serubiri echoed Enwezor’s philosophy of thinking history in the present (a reconceptualization of Michel Foucault’s phrase) and raised the idea that the contemporary can feel troubling, given the ways in which the 1990s still feel present today. Following Ngcobo’s definition of the biennial as a specter in the present, Serubiri suggested that the Second Johannesburg Biennale’s catalog, titled Trade Routes, remains a crucial art-historical resource that promotes an understanding of “the interconnection between artists and new constructions of art history as they happen in the present.” Such constructions are exemplified by the way the Trade Routes catalog, and in particular Julia Kristeva’s essay “By What Right Are You a Foreigner?,” became foundational for the Center for Historical Reenactments’s 2010 program “Xenoglossia,” which responded to xenophobic attacks against migrant workers in South Africa.

Tell Freedom

Nkule Mabaso’s conference presentation, “Tell Freedom,” dealt with the exhibition catalog for “Tell Freedom: 15 South African Artists,” a 2018 exhibition she curated with Manon Braat at Kunsthal KADE in the Netherlands. The presentation considered the practice of citation as a form of self-production and reproduction. By taking seriously the idea of the publication as an extension of the physical exhibition beyond its run at the Kunsthal, Mabaso suggested that the texts were not “about” the exhibition but instead extended its conceptual space. Given that the exhibition was concerned with the colonial encounter between The Netherlands as an imperial power and two other countries—Suriname and South Africa—the short catalog essays (from Manon Braat, Nkule Mabaso, Zahira Asmal, Nomusa Makhubu, Margriet van der Waal, Thulile Gamedze, Jessica de Abreu, Jyoti Mistry, and Simone Zeefuik) explored moments of plurality and transnational recognition emerging in the interstices of the settler-colonial context. (The exhibition did not consider the current colonial presence of the Dutch in the Caribbean.)

Exhibition installation image of “Tell Freedom: 15 South African Artists,” Kunsthal KADE, 2018. Curators Nkule Mabaso and Manon Braat. Image courtesy of Natal Collective.

The title of the exhibition and its catalog, “Tell Freedom,” was drawn from a 1954 memoir by South African–born journalist, novelist, and political writer Peter Abrahams. Published when Abrahams was thirty-five, Tell Freedom: Memories of Africa chronicles the author’s journey from South Africa to England at the age of twenty in search of opportunities and individual fulfillment beyond the strictures of racial apartheid. After Abrahams left South Africa in 1939, he found fame with his debut novel, Song of the City (1945). His subsequent novel, Mine Boy (1946), was the first by an African writer to attract major international acclaim and remains his best-known work.23

For Abrahams, diaspora was the border between home and the world, and also the geographic space where he first experienced the possibility of a life where a person can make themself into something. In Abrahams’s case, transcontinental travel produced in physical space an encounter akin to what is offered by the page: a site for citation, indexability, and ultimately reproducibility through a politics of recognition. Recognition at home, though, was denied to Abrahams, who never returned to South Africa. He lived in Jamaica from 1959 onward, until he was murdered there in 2017 at age ninety-seven. His literary oeuvre still lacks “official” recognition in South Africa.

As Mabaso noted in her panel presentation, “Taking the story of Tell Freedom and Abrahams’s articulation of his life and his aspirations about why he has to leave South Africa in order to go into the world was a starting point for the artists we selected” for the 2018 exhibition. There are contrasts and parallels between Abrahams and the exiled South African journalist Nat Nakasa, who was the subject of a work in the exhibition—namely, Kemang Wa Lehulere’s installation series Do Not Go Far, They Say, Again 5 (2015). This work is based on an earlier performance in which Wa Lehulere “draws on the history of South African writer Nat Nakasa, who exited South Africa in 1964 and spent a year in the US before his alleged suicide (falling from a high-rise building) in 1965.”24 In 2013, Nakasa’s remains were finally repatriated to South Africa from his grave in Upstate New York, marking an “official” recognition and return.

Wa Lehulere’s practice reexamines the narratives of Black artists who tried to live and engage in creative production outside of South Africa. Such a reexamination aims to “combat historical erasure by revealing the gap between individual biography and official historiography.”25

Portrait of Peter Abrahams. Carl Van Vechten, 1955. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Abrahams, who died in the diaspora, did not have a “hero’s return,” posthumously or otherwise, unlike the current crop of contemporary artists who can circulate through the globalized art market with ease and elasticity. The double violence of Abrahams’s exile from South Africa and his murder in Jamaica produce what Homi Bhabha calls “conditions of extraterritorial and cross-cultural initiations.” The result is not only alienation but a situation in which “the intimate recesses of the domestic space become sites for history’s most intricate invasions.”26

Bhabha’s concept of the “unhomely” is also visible in a work by Lebohang Kganye produced especially for Mabaso and Bratt’s exhibition. Kganye worked with another artist, Yoav Dagan, to create a diorama using silhouette cutouts of family members and other props drawn from photographs. In Kganye’s words, the installation “confronts conflicting stories, which are told in multiple ways, even by the same person.”27 Here, intimate narratives of emotional vulnerability reveal the temporal displacement of negotiating between individual biography and official historiography. As Kganye notes, family “archives do not reveal easy answers, for me they reveal that time can break apart and reconnect and not quite fit back into one another.”28

Mabaso explained that Lebohang Kganye, Kemang Wa Lehulere, and the other artists in “Tell Freedom” engaged with social, economic, and political disparities resulting from history—not only to elucidate the present but also to question various assumed positions within fraught societal contexts. By taking historical context as a thing to be cited, without necessarily (re)telling “history,” the exhibition is a form of knowledge production above textuality. Similarly, the publication, as its extension, goes beyond narrativity. Artistic practice, then, becomes a particular form of remembering, validating, taking care, and bearing witness in ways that intervene within the constitutive site of history and its impact on the present.

Conclusion

By invoking eighteenth- and nineteenth-century history—such as the Haitian Revolution and the Chimurenga in Southern Africa—and transnational trajectories not only of artists and writers but of exhibitions, the panel on “Citational Practices” moved away from a tendency towards the nationalization of discourse. This movement is one of the gestures that makes solidarity and reproducibility possible. In a country such as South Africa, understanding mechanisms of knowledge production is crucial to critically evaluating constructs that are predicated on grand narratives of colonial and/or anti-colonial struggles. The situation is further complicated by oversimplified metanarratives of history that uphold a superficial dichotomy of dominance and subordination or resistance. By contrast, the panel attended to the complexities of decolonial approaches to historical phenomena and their bearing on the contemporary. While the agenda of the speakers was familiar, together they displayed a diversity of approaches to the practice and recent history of citation within art.

Annabel L. Kim, “The Politics of Citation,” Diacritics 48, no. 3 (2020).

Legacy Russell, “On Footnotes,” lecture delivered at Vera List Center, New York, November 29, 2021.

Lucy Steeds, “What is the Future of Exhibition Histories? Or, Toward Art in Terms of Its Becoming-Public,” in The Curatorial Conundrum: What to Study? What to Research? What to Practice?, ed. Paul O’Neill, Lucy Steeds, and Mick Wilson (MIT Press, 2016).

“SOUNDGARDEN—A Live Reading for Bessie Head’s 85th,” organized by architect and writer Ilze Wolff, was broadcast on Chimurenga’s Pan African Space Station on July 13, 2022 →.

See the curatorial statement for “When Rain Clouds Gather” →.

Bessie Head, “Gladys Mgudlandlu: The Exuberant Innocent,” New African 2, no. 10 (November 1963). For more on Gladys Mgudlandlu, see Zamansele Nsele, “Gladys Mgudlandlu Painted Land(e)scapes that Bent the Genre to Her Will,” post: notes on art in a global context, May 26, 2021. The book Surfacing: On Being Black and Feminist in South Africa (2021), edited by Desiree Lewis and Gabeba Baderoon, has contributed to a history of texts on African feminism. We would be remiss not to mention the career retrospective of artist Tracey Rose, “Shooting Down Babylon,” organized by the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in 2022, which recently toured to the Queens Museum (2023), and the recent solo presentations of Dineo Seshee Bopape at the Museum of Modern Art (2023) and ICA Virginia Commonwealth University (2021).

Abstract for “US-SA Feminist Solidarities: Citational Practices in the Visual Arts,” in Feminist Readings in Motion?, conference booklet, University of South Africa College of Human Sciences, 2021 →. A second, related panel, “The Page as Site: Fostering Solidarities through Citational Practices,” was held virtually at the Space for Black Creative Imagination at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, Maryland, in 2021. This discussion, which built on foundations established by “US-SA Feminist Solidarities,” again included Ntombela, Serubiri, and Mabaso, with additional panelists Fitsum Shebeshe and Raël Jerro (as moderator and discussant).

Portia Malatjie, “Queering Ancestry: Transgenerational Communion with Oneself,” paper presented at “Feminist Readings in Motion?,” online, April 12–16, 2021.

Ngugi wa Thiong’o, “Land, Language, and Life,” lecture delivered at the Conference on Land Policy in Africa, Kigali, Rwanda, November 1–4, 2021.

Greer Valley, Unsettled (Dakar Biennale, 2022), 2–3. Exhibition catalog.

Valley, Unsettled, 2–3.

Malatjie, “Queering Ancestry.”

Imani Jacqueline Brown, “A Minor Constellation of Black Ecologies: Introduction,” MARCH, no. 2, “Black Ecologies” (Fall 2021): 11.

Kim, “The Politics of Citation.”

Kim, “The Politics of Citation.”

Nontobeko Ntombela, “Untranslatable Histories in Tracey Rose’s Hard Black on Cotton,” in The Stronger We Become, ed. Nkule Mabaso and Nomusa Makhubu (South African Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2018). Exhibition catalog.

“I stood at the border, stood at the edge and claimed it as central.” Toni Morrison quoted in Jana Wendt, “Interview with Toni Morrison,” Uncensored, Australian Broadcasting Service, 1998 →.

Kellie Jones, “Tracey Rose: Postapartheid Playground,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 19, no. 1 (2004).

Jones, “Tracey Rose.”

Jones, “Tracey Rose.”

Gabi Ngcobo, “Endnotes: Was it a Question of Power?,” in Condition Report: Symposium on Building Art Institutions in Africa, ed. Koyo Kouoh (Hatje Cantz, 2012).

Ngcobo, “Endnotes.”

Nkule Mabaso, “Aesthetics and Other Priorities,” in Tell Freedom: 15 South African Artists (Kunsthal KADE, 2018). Exhibition catalog.

Mabaso, “Aesthetics and Other Priorities,” 76.

Mabaso, “Aesthetics and Other Priorities,” 76.

Homi K. Bhabha, “The World and the Home,” Social Text, no. 31–32 (1992).

See →.

Quoted in Mabaso, “Aesthetics and Other Priorities,” 80.