Naoki Sutter-Shudo addresses the current critical landscape with a series of seven “Critical Figures” and twelve paintings. Installed in only one half of the gallery, the audience of figurative sculptures faces a wall on which is hung a row of large graphic canvasses. Each is adorned with a formal accessory made of flimsy material: a wire twist-tie shaped into a tie, a fake lettuce hat, a shirt made of bubble wrap or a plastic bag. The figures’ apparent attempts to present as professional are rendered ridiculous by the nature of their clothing. They look as though they’re dressed for a nineteenth-century salon—complete with bonnets, big collars, and ties—rather than a contemporary art gallery. Each figure’s body has an intricately constructed apparatus holding a wind-up metronome with a bell (some in 3/4 time, others in 1/4 time) and has a unique look, height, and facial expression tending towards the bizarre—one has three heads, for example.

The viewer is able to wind up the “critics,” letting them spin their wheels while looking around the show. The result is a rhythmic kind of chatter punctuated with the ding of a bell, as if to signal a lightbulb moment. Sitting atop stacks of white archival boxes crudely labeled with the names of various art and culture magazines, from Frieze to Vanity Fair, the critic figures appear to have emerged from, or will soon return to, a storage space, resigned to a life of stasis contingent on the vitality of their publications. (At the opening, a bouquet of flowers gifted to the artist lay on the boxes labeled Artforum like an offering on a grave.)

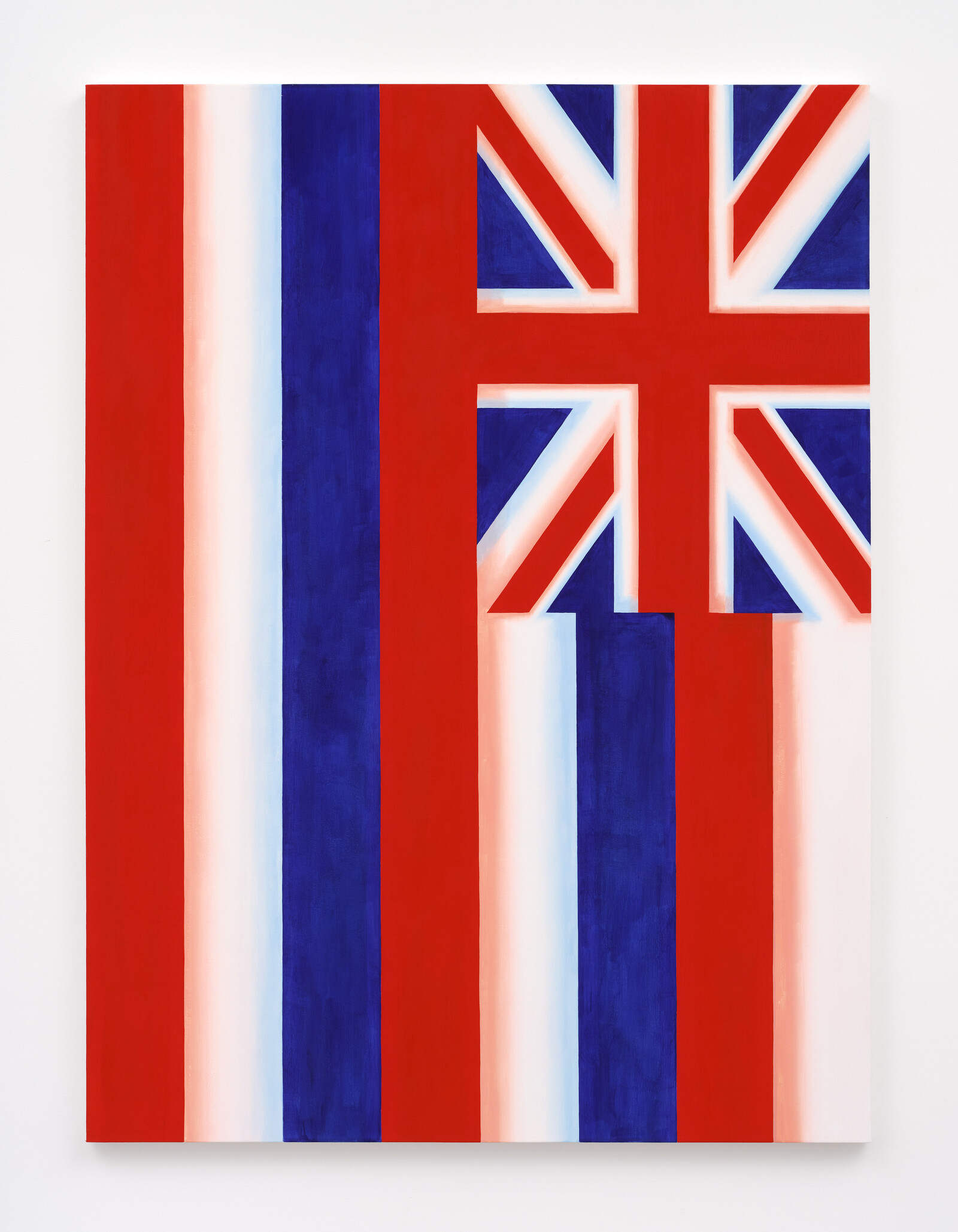

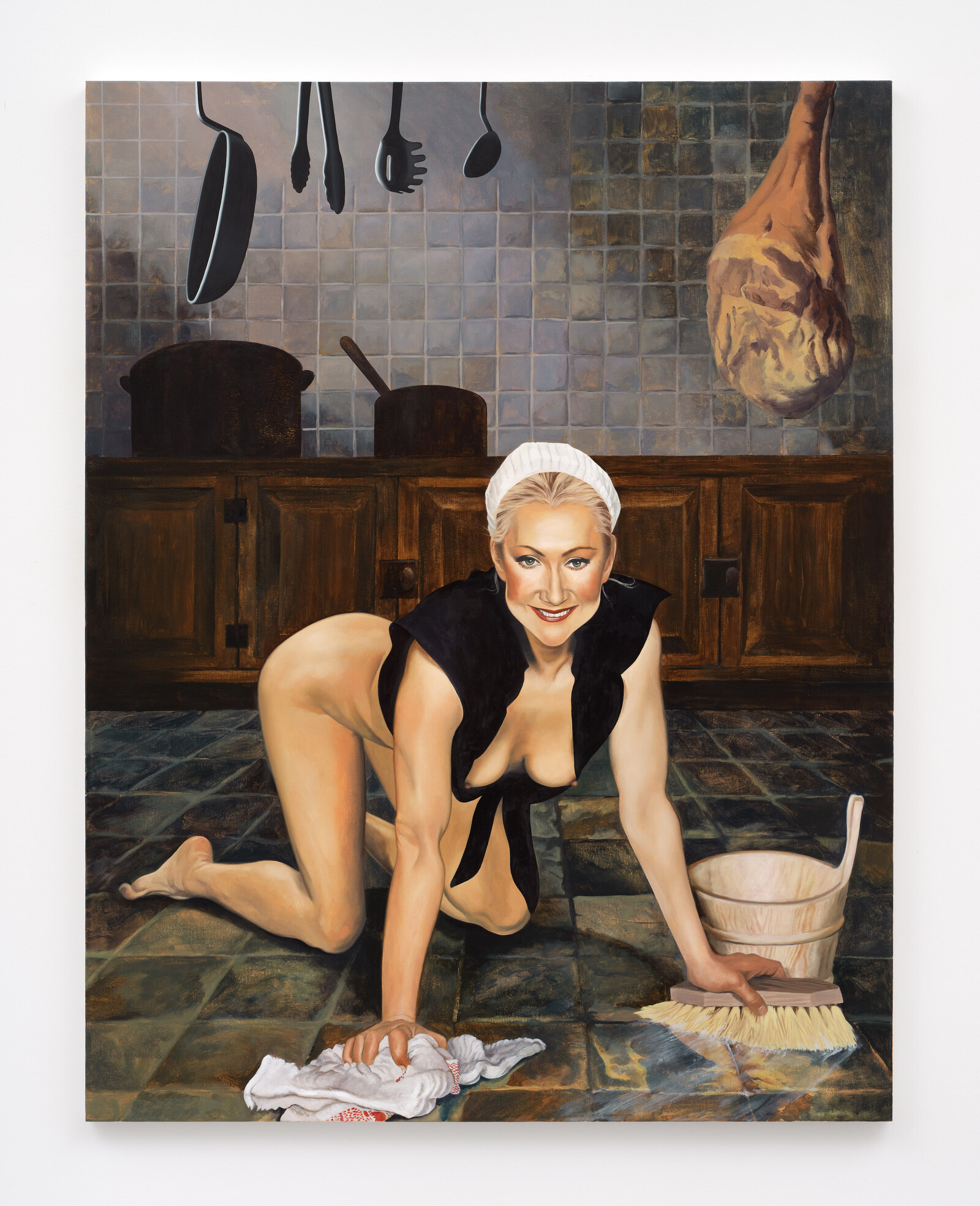

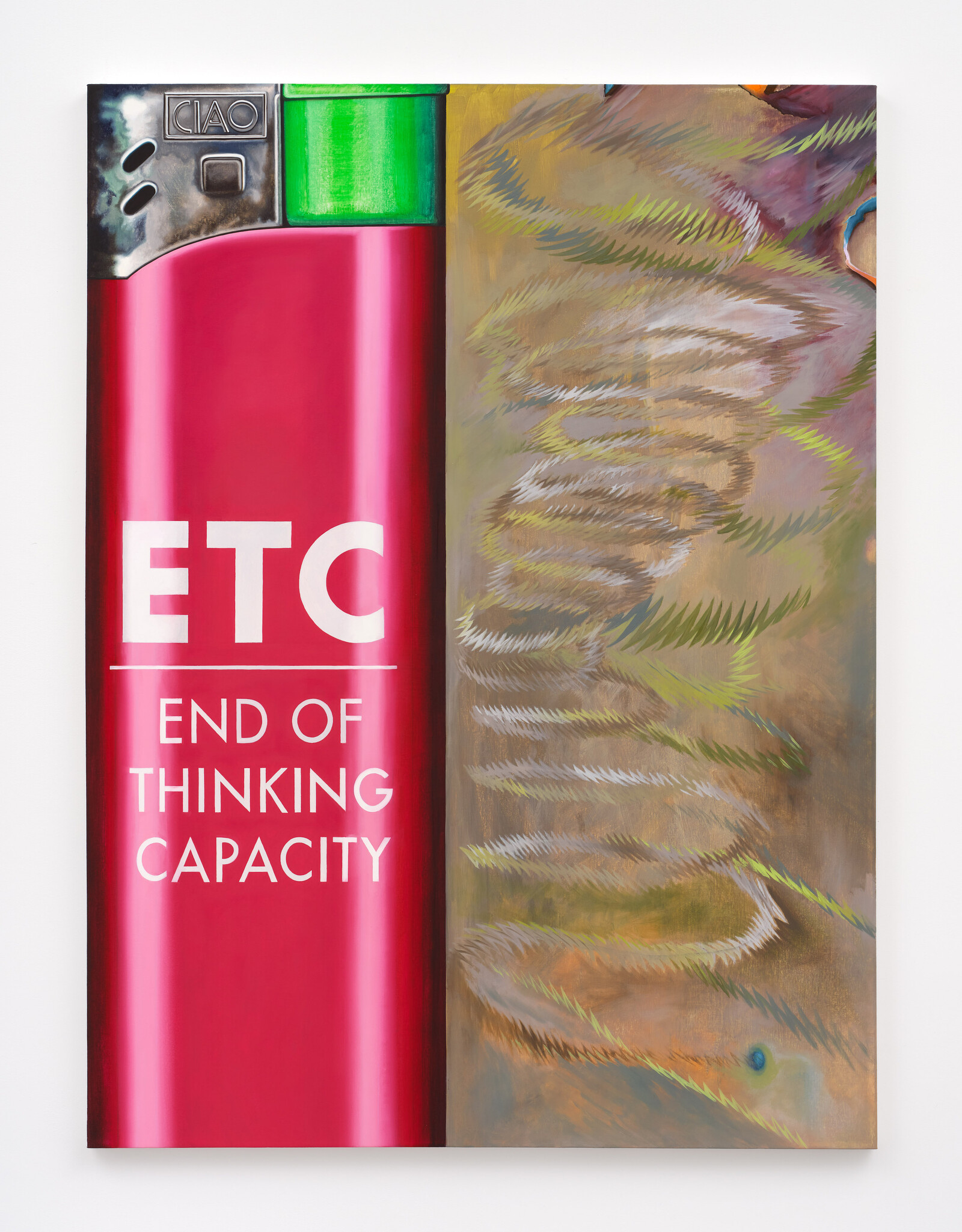

The twelve paintings invoke a number of styles and subject matter—some taken from other painters, including a scaled-up reproduction of a painting by the artist’s wife Alexandra Noel, of an image from a French cigarette label—and depict among other things a Hawaiian flag turned through ninety degrees, the mother of Marine Le Pen as a slutty French maid in an image taken from a 1987 Playboy shoot, and a lighter bearing the name of the exhibition and the acronym that means it is sometimes, falsely, cited as an etymology for the abbreviation of et cetera. The works almost exist as stand-ins for the Big Paintings that dominate the art world Sutter-Shudo seems to be responding to, yet these well-executed examples do not feel ironic or cynical so much as whimsical.

The common gripe that there isn’t any “real” criticism is often paired with the complaint that people only want to show/buy/talk about Big Paintings. That an artist’s success is solely determined by market value can seem to push criticism into redundancy. “End of Thinking Capacity” brought to mind conversations with my peers about the state of criticism, especially in Los Angeles, where it can feel that criticism functions as an extension of the PR apparatus. One potential reading of Sutter-Shudo’s ghoulish sculptures is that they lament this state of affairs: all the critic has left, in this vision, is her outdated clothing and an automated wagging finger. In this sense, the show might be read less a swipe at the critics themselves than a critique of the flimsy infrastructures that support them.

“End of Thinking Capacity” suggests the industry creates limitations for both artist and writer. Sutter-Shudo embraces the freedoms available to the former, but the title of the show suggests finality, a paradigmatic shift, an End for which the artist offers no solution. While the vitality of the work hedges against bitterness, another reading of this exhibition is possible: that it presents a kind of nostalgic fantasy of the antagonistic relationship between critic and artist. In other words, it’s a provocation to writers. Perhaps these figures end up being self-portraits—the “critics” that live in the artist’s head.