When it comes to a work of art, what is the measure of time that matters? It’s easy to point to where a work of art takes place: to the gallery in which it is installed, the place on a map where an earthwork is sited; even the extent of air in which a voiceover sounds possesses a clear spatial dimension. But to ascribe a time to a work of art is a far more difficult process. Is its time that which has elapsed since its creation, or the time when it is viewed? Does a work last as long as its material, be that marble or data, or only as long as it is remembered? Perhaps all these times matter, and more—but if the times of art are multiple, then which do we privilege, and why?

For the past few years, the only time that has seemed to matter to many museums and galleries has been that of an artist’s rediscovery. A living artist is summoned up from unjust obscurity, their forgotten work presented with fanfare: now, at last, its time has come. And if the surest sign that something is happening is a shift in the market, then a wave of rediscoveries is well underway. In 2016 the invincibly shameless “How To Spend it Section” of the Financial Times reported that “[w]e are currently seeing a series of dramatic comebacks for once-celebrated artists from around the globe.”1 “The word ‘trend’ doesn’t do it justice,” stated Katerina Gregos, who as artistic director of Art Brussels added a “rediscovery” program to the fair. “Old is the new black,” asserted the New York gallerist Alexander Gray, perhaps inadvertently patronizing two demographics for the price of one. By 2017, dealers at Art Basel Miami were speaking of a backlash: “not everybody needs to be revived,” proclaimed the gallerist Garth Greenan.2

These investment-driven reappraisals do a disservice to the careful curatorial work that produces shows like “Black in the Abstract” parts I and II (2013–14) at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston, or Park Seo-Bo’s series of “Ecriture” exhibitions in London’s White Cube from 2016 to 2018. Such scholarly efforts are often portrayed as countering a presentism which is only interested in art which addresses today’s concerns, or which only turns to art from the past when it seems directly to relate to the present. Yet every act of rediscovery threatens to impose a temporal relationship with art no less limited than the presentism it rightly aims to correct, a limitation all the more glaring when the artist in question is still alive. For something to be rediscovered in a present, it first must be assumed to belong to a past, because only then can it serve as a reminder of what a present has forgotten. It assumes that the most important time of a work of art is the historical context in which that work was created. To present art as rediscovered relies upon measuring it against an external, and often very linear, narrative of history. But works of art are more than simply notches on a timeline of art-historical progress. Outside of the cycles of being forgotten and rediscovered by institutions, they offer us their own ways of measuring and being in time.

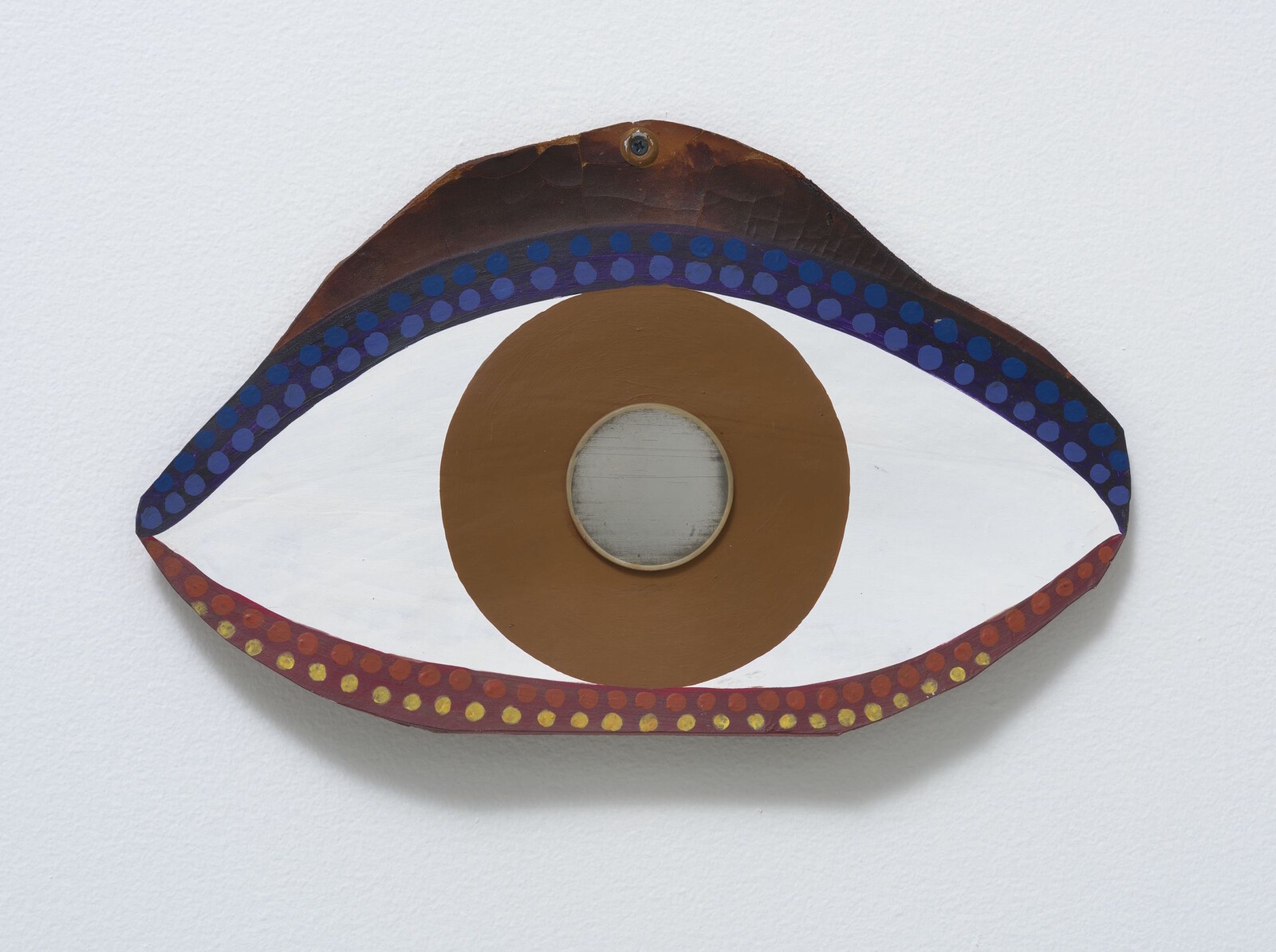

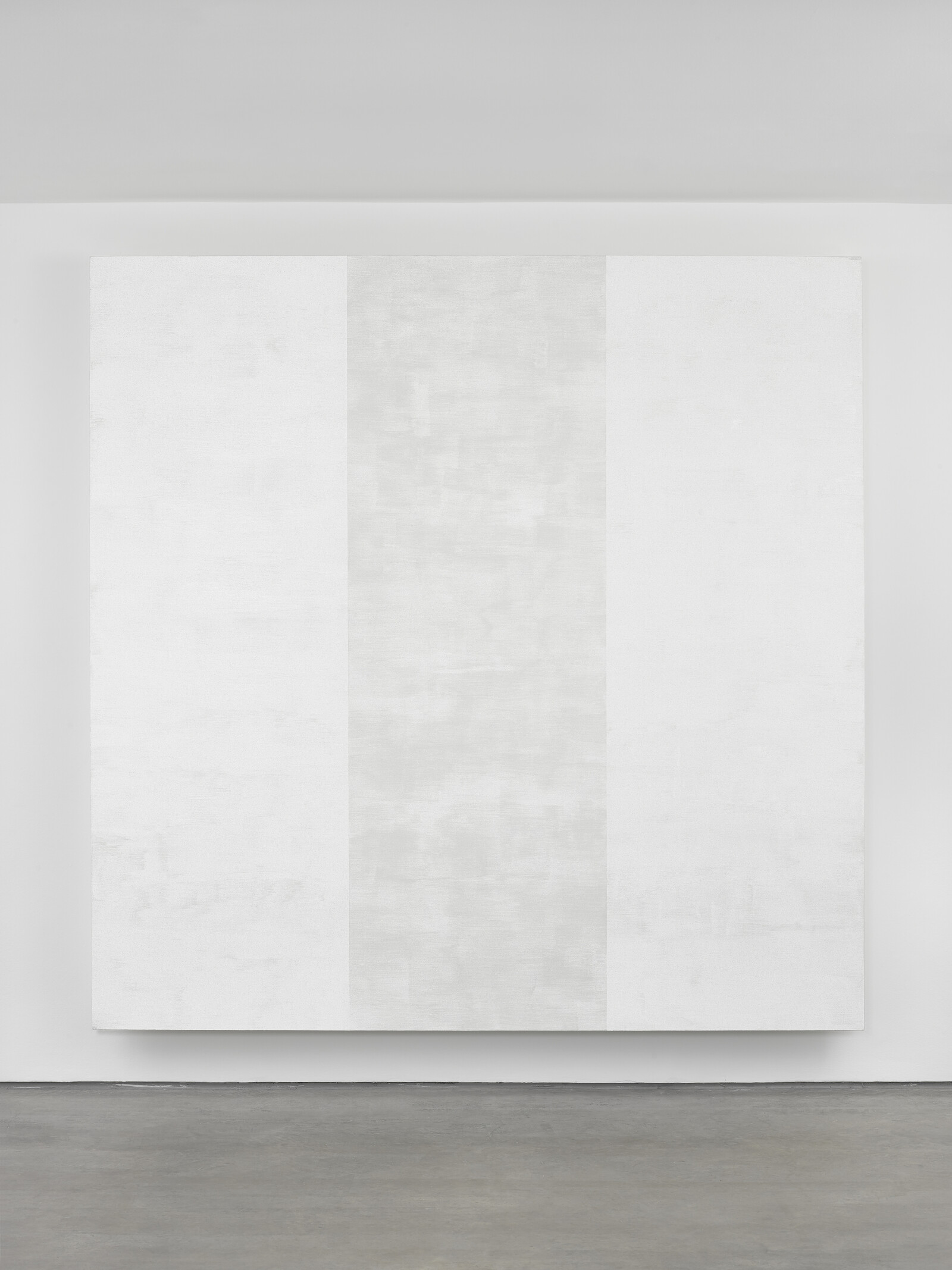

In 2018 the American painter Mary Corse, then 73, had her first solo museum exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, and her first major solo show in the United Kingdom at Lisson Gallery, London. Corse began her career in the mid-1960s, in California, producing monochrome paintings in the idioms of US minimalism. Her interest lay not in the materiality of these works’ objecthood, but in the play of light reflected from the paintings: subtle gradations of white on white. She then turned to producing light boxes, using technology to produce similar effects. Over the course of her long career, she moved back and forth between painting canvases and deploying technology to find ways of depicting what she called “the reality of our moment.” 3 That same year, four of Corse’s paintings were purchased by Dia Beacon, the temple of American Pop and minimalism; Dia Art Foundation’s director, Jessica Morgan, admitted that it was “kind of confounding that we were not aware of her work.” 4 Corse had officially been rediscovered, her career serving to correct an art-historical story by demonstrating that minimalism was not an entirely male-dominated preserve. Yet, in comfortably slotting her paintings in beside works by Sol LeWitt or Dan Flavin, that art-historical story is also reinforced.

In one of Corse’s recent paintings, Untitled (White Inner Band, Beveled) (2018), glass microspheres are affixed to a white canvas in three horizontal bands of differing density. The spheres refract light, so that as you move around, or as the day passes, the appearance of the painting changes. The object persists in time, but what the viewer sees changes with time. This tension between an artwork’s essence and appearance, while latent in all our encounters with art, became so pressing in the 1960s for artists as different as Lygia Clark and Robert Morris that it led to minimalism precipitating the wholesale dematerialization of the art object into conceptualism, institutional critique, and theoretical discourse. The narrative that enables an artist like Corse to be “rediscovered” relies in part on this reading of art history, wherein painting died sometime in the 1960s, and was reborn in an endless dialogue with the possibility of its own existence. But viewing Untitled (White Inner Band, Beveled) alongside an early work like Untitled (Light Painting) (1971), a large, pale straw-colored canvas with small white squares in each corner, you notice that the surfaces of these painting are also fleeting, amid ever-changing interactions of light. There is a continuity across the time of Corse’s practice, in which the tension between the material work and its perception remained in balance, repeatedly manifest in the production of canvases whose “reality” is never fixed, but always rests in a transient play of light, the medium that is time’s very limit.

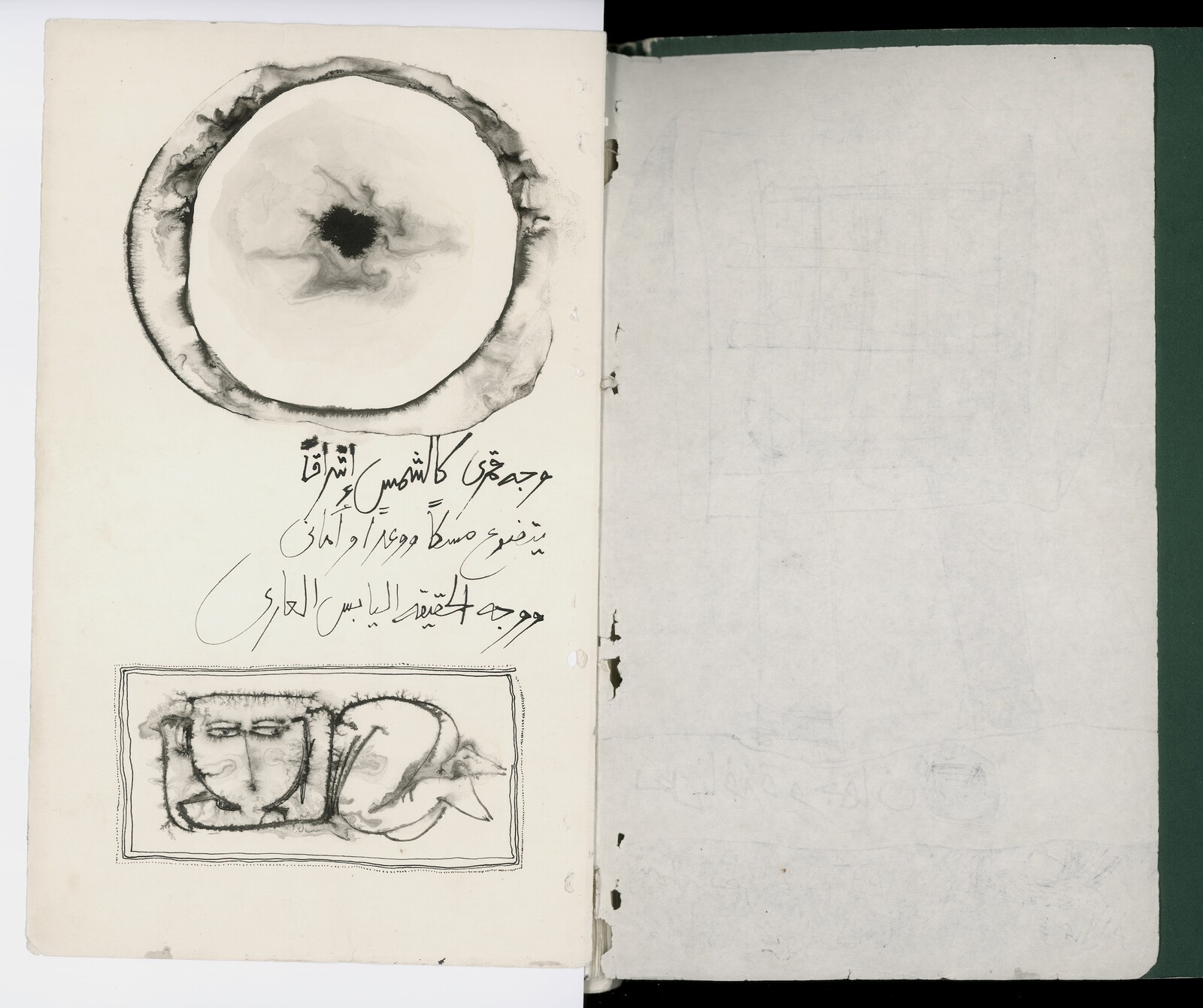

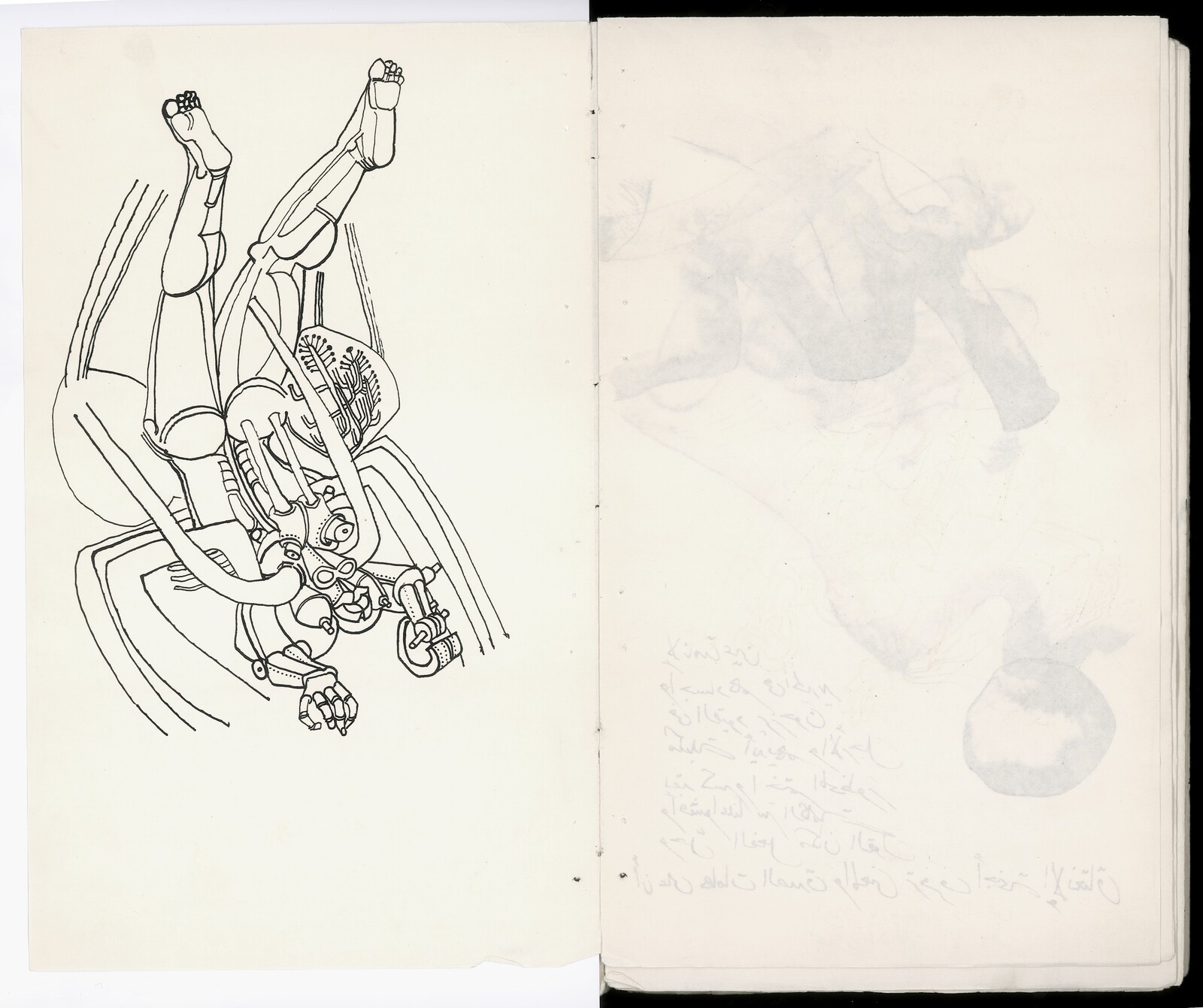

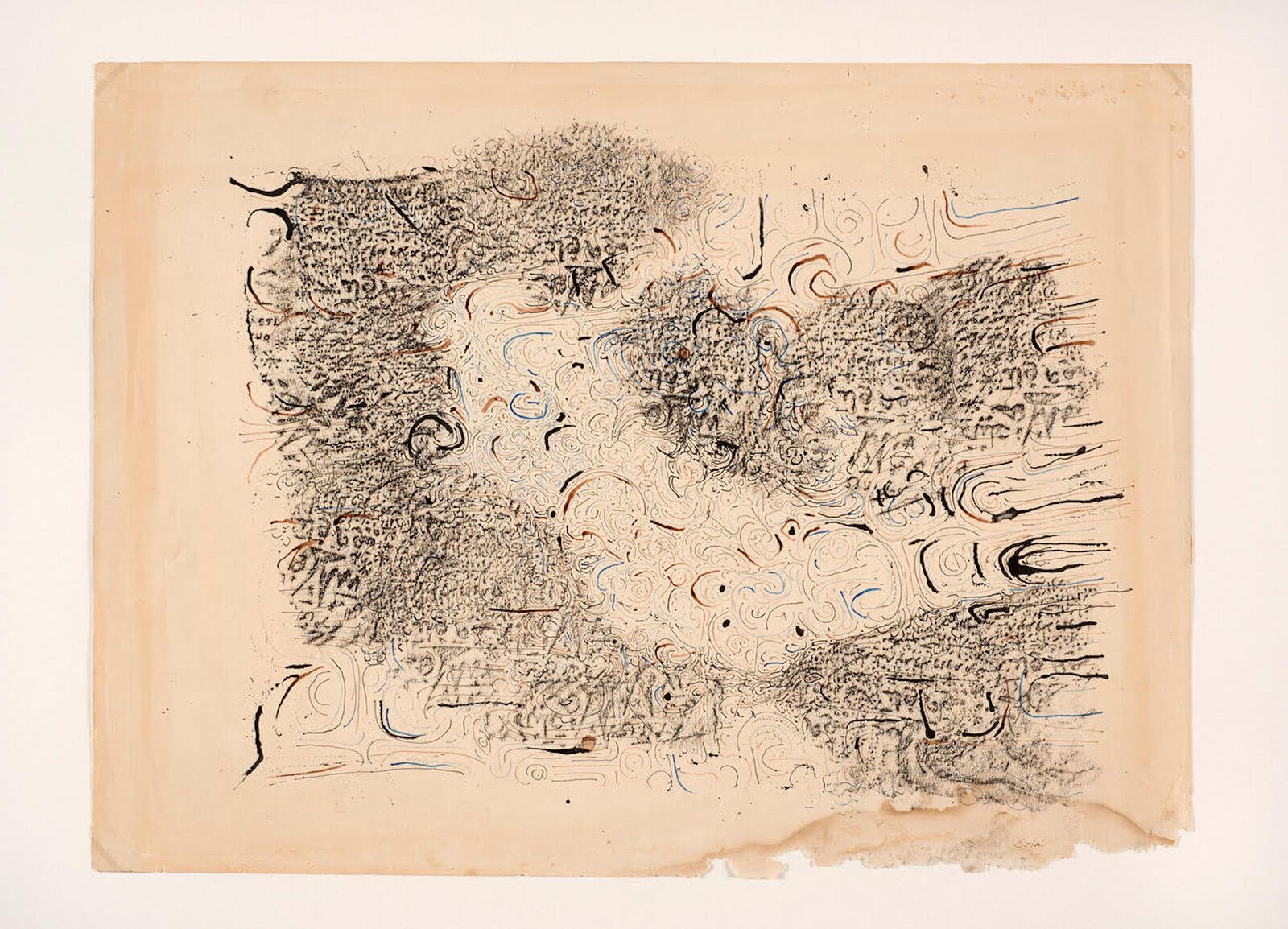

The historical narratives in which we situate works of art can be far larger than those produced by the whims of the market. In 2012, the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi had his first major retrospective at the Sharjah Art Museum in the UAE, which travelled to London’s Tate Modern in 2013. El-Salahi was born in Omdurman in 1930 and studied painting in London, before returning to become a leading figure in the Khartoum School, a group of artists who sought a new abstract artistic language for Sudan when it gained independence from the British Empire in 1956. El-Salahi’s turn to abstraction came from his observation of the role of calligraphy in everyday life across Sudan. The promise of abstraction as a unifying national language, suggested in a drawing like Untitled (1965), which oscillates between calligraphic ornament, abstract patterning, and desert landscape, lay not in the promise of a utopian future to come—as, say, in Soviet modernism—but in abstraction’s already existing presence in the nation.

While incarcerated, for six months, in Khartoum’s Kober prison, El-Salahi used smuggled pencils and paper to record his experiences in his Prison Notebook (1976). The final image in the notebook is a strange figure, part animal, part human, part machine, which El-Salahi described as “the whole machinery of the state” turned upside down.5 It is an image of the decolonial state transformed into a mutant, imprisoning its own people. The notebook was purchased by the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 2017, and presented as part of a permanent display illustrating the museum’s newly globalized history of modernism. The diminutive pages of the Prison Notebook anchor a display about art and war in the 1970s, one of a series of rooms which present artistic modernism as a response to warfare: the industrial destruction of World War One; the Holocaust. In this positioning, both El-Salahi’s anticipation of a new visual language for an independent state, and the disappointment enacted in the notebooks when that state imprisoned him, pulls the art of decolonization into the orbit of a still-incomplete global modernist project. But it’s not at all clear, as the political theorist Adom Getachew pointed out, that African peoples, in the era of decolonization, saw the founding of their states as a stage on the path to the same kind of modernity already extant in Europe and the Americas. 6 The hopes and disillusions of the unfinished processes of decolonization are not necessarily analogous with narratives of modernity propagated elsewhere. The experiences of time recorded in El-Salahi’s prison notebook become harder to read if we measure them against the assumed progress of modernism.

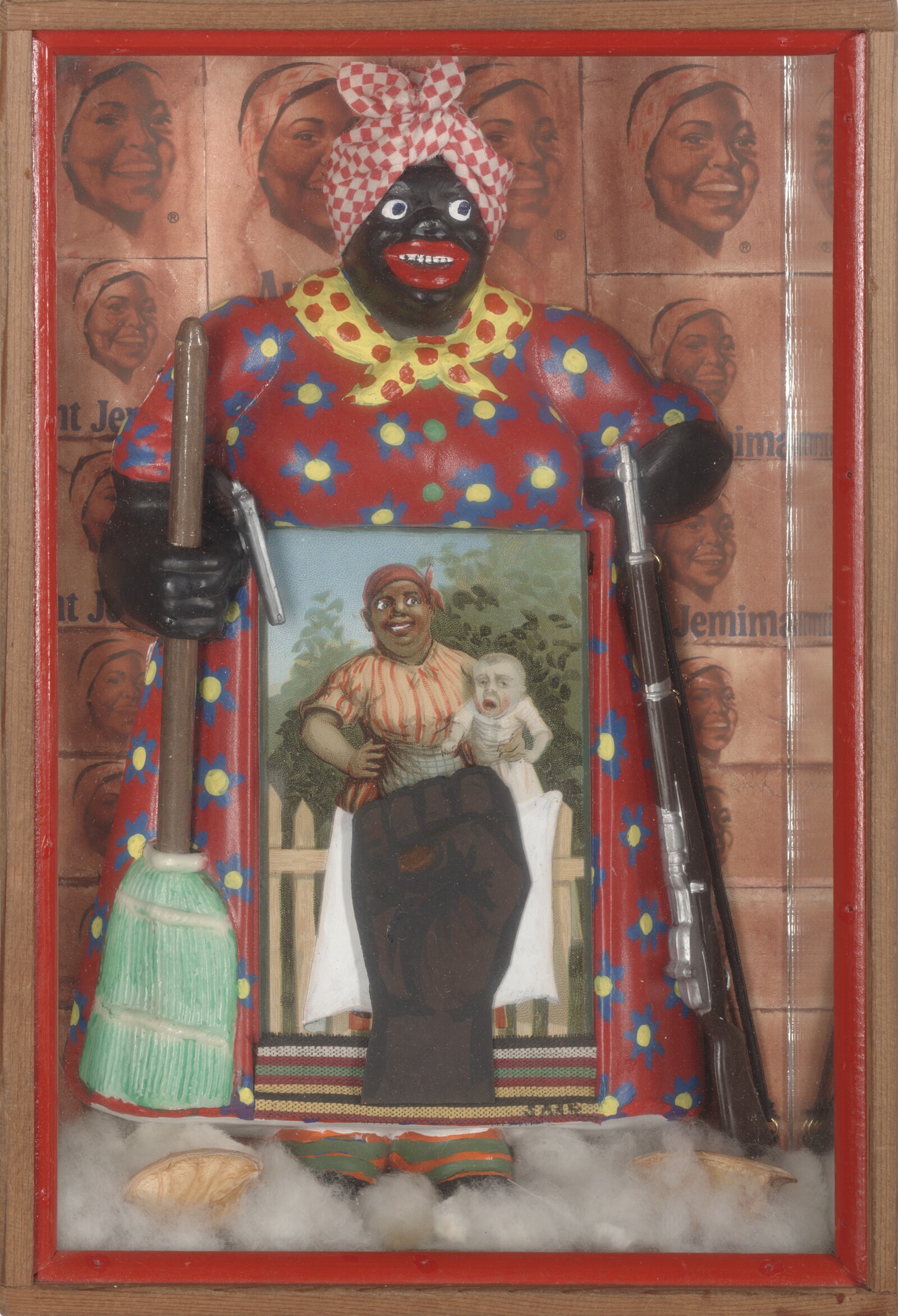

In some cases, the time of art is simply that of persistence. In 2017, Tate Modern exhibited Betye Saar’s The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972) as part of “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power.” In Saar’s assemblage, a postcard of a smiling black maid is held by a statue of a smiling black maid, inside a box whose background is a repeating print of another smiling black maid. This image, of black women happy in servility, is repeated over and over again. It’s a potent illustration of one way in which racial domination works: if you repeat the same lie often enough, people will start to believe it. Yet the heroine of Saar’s assemblage disrupts this repetition: as well as her postcard, the statue of Aunt Jemima is grabbing a gun, instigating the break of a revolution. But there was something incongruous about viewing Saar’s work within an exhibition which billed itself as a diversification of the Tate’s program, aiming to draw attention to a historically neglected period of black art (but neglected by whom?). It presented Saar’s work as a piece of art history, illuminating an era of past racial struggle as a means by which to inform our own. Here was Saar rediscovered, as she has been presented often in years since, in exhibitions like “The Legends of Black Girl’s Window,” first shown at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 2019 (and intended to tour to LACMA, Los Angeles, and the Museum Ludwig, Cologne). But Saar, who turns 94 next month, is still very much alive, and she is bored of being rediscovered: “I’m so really tired of it already.” 7 Neither Saar, nor The Liberation of Aunt Jemima, nor the racism it explores, have stopped being present since the 1970s. When, exactly, is the past from which this work is being excavated?

Corse’s light, Salahi’s mutant, Aunt Jemima’s smile: to rediscover each of these artworks is to first assume they have been forgotten; to imprison them within a past that is safely distant from us on the steady unfurling of an art-historical timeline. Yet each offers its own shaping of time: the flux of light across a single day; the ongoing existence of racism, and of the rebellion against it. These shapings cut across the linear progress from past to present required by the institutional time of rediscovery. Were their implications grasped, they would serve those institutions better.

Pernilla Holmes, “The comeback kings and queens of art,” Financial Times (May 20, 2016), https://howtospendit.ft.com/art-philanthropy/106921-arts-comeback-kings

Julia Halperin, “The Rediscovery Backlash: Has the Market for Overlooked Art Historical Talent Peaked?” artnet (December 8, 2017), https://news.artnet.com/market/abmb-market-report-rediscoveries-1173188

“Studio Visit with Mary Corse, Whitney Museum of American Art website https://whitney.org/watchandlisten/37855

Charlotte Burns, “Market Analysis: Mary Corse”, in other words (May 10, 2018), https://www.artagencypartners.com/mary-corse/

Ibrahim El-Salahi, Prison Notebook, ed. Salah M. Hassan (Sharjah Art Foundation; Sharjah The Museum of Modern Art; 2018) p. 35

Adom Getachew, Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019)

Jonathan Griffin, “An interview with Betye Saar,” Apollo (November 16, 2019), https://www.apollo-magazine.com/the-way-i-start-a-piece-is-that-the-materials-turn-me-on-an-interview-with-betye-saar/